|

by Andrew Collins

from

AndrewCollins Website

The three main Giza

pyramids, as viewed from the edge of the Maadi Formation When I wrote THE CYGNUS MYSTERY, I knew that among the many incredible claims it would make, one alone would court fierce criticism, and this was the apparent connection between Giza and the Cygnus constellation. Over the years I have seen how other new theories concerning the hidden mysteries of the plateau have been ripped to shreds by detractors, and then dissected piece by piece until nothing is left intact.

It started with the theories contained

in Robert Bauval and Adrian Gilbert's seminal classic THE ORION

MYSTERY back in 1994, and has continued ever since with any

theory that veers even slightly away from the straight and narrow

path of orthodoxy Egyptology. Yet strangely, it is not usually the

Egyptologists who start the carnage, but other researchers and

writers in the fields of either revisionist history or

archaeoastronomy, neither of which are accepted as mainstream

subjects.

Thus when my friend and colleague Rodney

Hale rung me excitedly one morning in January 2005 to say that he

had superimposed the three 'wing' or 'cross' stars of Cygnus (Gienah,

aka epsilon Cygni; Sadr, aka gamma Cygni, and delta Cygni) with the

Giza pyramids and it was a perfect match, I knew then that if this

were ever to reach publication then it was going to cause a furore

that would eclipse anything I had ever written before about Ancient

Egypt.

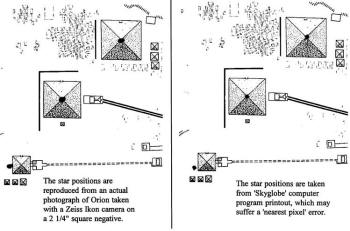

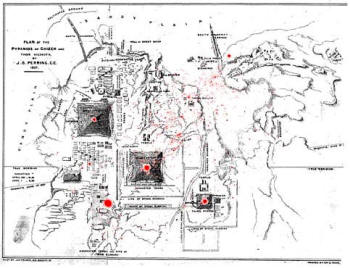

Relative positions of the three 'belt' stars of Orion as overlaid upon the Giza pyramids as done by Rodney Hale in 1995, using both a photograph of the stars

and as they appear in

the Skyglobe program 3.5 They simply do not match, with the star corresponding to the Third Pyramid, Mintaka (delta Orionis), falling towards the southwest edge of the monument. Of course, the whole thing could simply have been a symbolic gesture on the part of the Ancient Egyptians, and thus was not meant to be precise. Yet still, it was a shame that the correlation was not exact.

Even more despair came for Rodney, a technical engineer by trade, when he attempted to match the remaining stars of Orion with other pyramid fields, as is proposed by Bauval and Gilbert in THE ORION MYSTERY.

Map of the Orion constellation

Even more confusing was that Orion's two brightest stars Rigel (beta Orionis) and Betelgeuse (alpha Orionis) do not mark an ancient monument of any kind. Once again, the correlation might not have needed to be precise, but it was a shame that the theory was not as tight as he might have liked it to be. Proposals of this kind need precision for the soul to take them seriously.

Orion superimposed

(upside down) on 1927 map of Cairo, showing So now it seemed that for Rodney the 'wing' stars of Cygnus, linked to the plateau through its associations with the cult of Sokar - a falcon-headed god of the dead who presided over Rostau, ancient Giza, and was the earthly counterpart of the celestial sky falcon god dwn-'nwy - could be superimposed over the three main pyramids.

The simple answer is that neither of us

could be sure. However, I decided to publish these controversial

findings in THE CYGNUS MYSTERY. Naturally, there was a certain

amount of hesitation, but I wanted for the Cygnus-Giza ground-sky

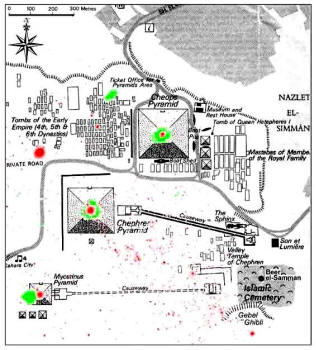

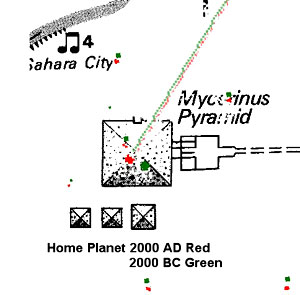

alignment to speak for itself. Ground-sky overlay using the stars of Cygnus on a modern map of the Giza plateau. The Cygnus stars are in red, with those of Orion's belt in green.

Actual photograph of

the stars were used for this purpose

MOUND OF CREATION

For instance, Albireo (beta Cygni), the 'beak' star falls in the area of Gebel Ghibli (Arabic for 'southern hill'), a curious rock formation a few hundred meters to the south of the Great Sphinx. Robert Bauval and Simon Cox in the former's book THE SECRET CHAMBER (1999) proposed that Gebel Ghibli might have acted as a physical representation of a mythological primeval hill, or Mound of Creation.

Cox had already investigated this

strange hillock, after it had been highlighted as significant in the

remarkable landscape geometry of David Ritchie. Cox sensed that it

held the key to locating the lost Shetayet shrine of Sokar, said to

have been somewhere in the area. Ritchie had felt that it was a

'gateway' into Giza's hidden dimensions.

It is dedicated to a holy man named Hammad el-Samman, said to have once occupied the well in some bygone age. According to a little known tradition still held by the village elders of Nazlet el-Samman (named after the saint), Hammad el-Samman guarded the entrance to an underground city or palace located beneath Nazlet el-Samman, which is due east of the Great Sphinx (where Edgar Cayce predicted that the Egyptians Hall of Records would be found).

Thus to find that the Cygnus star

Albireo, the mouth or gullet or the celestial bird, fell nearby,

albeit beyond the long linear stone structure known as the Wall of

Crows (see below), was interesting indeed, and worthy of further

investigation.

Strangely, most posts were fairly

positive, especially after able researchers went away and did their

own Cygnus-Giza overlay, and saw that it was accurate. Others,

however, would not even accept that Cygnus was known to the Ancient

Egyptians, never mind it being linked with the plateau.

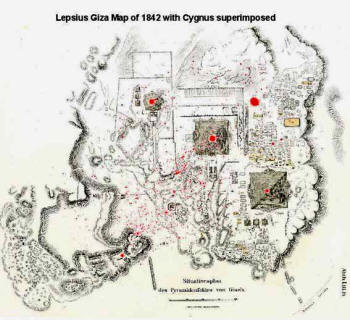

The Deneb spot covers a fairly large mastaba designated LG14, after the numbering of German Egyptologist Carl Richard Lepsius (1810-1884), who surveyed the plateau, and produced an impressive map dated 1842 (see below). The Lepsius map of 1842 showing the Cygnus stars overlaid in red.

Note the Deneb spot

obscuring mastaba LG14 on the edge of the Western Cemetery Lepsius found the tomb to be devoid of any artifacts or inscriptions, and thus it was simply catalogued and forgotten about. Nothing more is currently known about LG14, and there is every chance that, if not pillaged in ancient times, it was built but never used. As such, no further light can be thrown on the Deneb spot, as we refer to it.

Yet, strangely, just a few hundred meters away to the west is something curious marked on a map of the plateau made in 1837 by John Shae Perring (1813-1869), the British engineer and anthropologist who worked alongside Col Richard William Howard Vyse (1754-1853), the British soldier and anthropologist who investigated the monuments of Giza at this time. It refers to 'Excavated tombs and pits of bird mummies' in connection with an accompanying drawing showing a north facing entrance to an east-west running ridge, as well as several chambers in a line each side of a north-south corridor.

Other smaller rooms are also shown at the southern end of the cave-like catacomb. Further investigations by my colleague Nigel Skinner Simpson turned up only one reference to this presumed sepulchral monument of unknown age in Vyse's three volume opus OPERATIONS CARRIED ON AT GIZA (1837).

Volume I, page 238, states:

Sadly, Vyse makes no other references to this underground maze of tombs and pits, and so we learn no more about the 'part of a large bird ' that was removed, or why Perring's map refers to 'bird mummies' in plural. Yet it implies that this was some kind of catacomb similar to those found at nearby Saqqara, one of which was found to contain tens of thousands of hawks sacred to the god Horus.

These had been deposited as votive offerings over a several-hundred year period, c. 750-350 BC. She to whom were they offered at Giza? If not Horus, who is associated with the plateau in his form as Horemakhet (Harmakhet, Harmachis), ‘Horus in the Horizon', and is a name also for the the Great Sphinx - then Giza's 'tombs and pits' might well have been sacred to the falcon god Sokar.

However, Vyse's statement that part of a

'large bird' was removed does tend to imply an avian specimen larger

than the common hawk, kestrel or falcon. And why was this bird

catacomb to be found beyond the northwest corner of the plateau,

facing out towards the northern skies? It is a frustratingly,

baffling enigma.

Perhaps what we are looking for here is underground, or it is simply the position of a sight line overlooking the rest of the plateau. Either way, the Cygnus-Giza correlation should not be dismissed simply because Deneb does not hit anything obviously important, especially since Orion's own brightest stars, Rigel and Betelgeuse, fail themselves to mark any ancient monument. The John Perring's 1837 map of the Giza plateau. The Cygnus stars are in red. Note also the 'well' (Beer el-Samman) and 'sycamores' marked between the Great Sphinx and Gebel Ghibli.

Note also the

proximity of the 'beak star' Albireo (beta Cygni).

THE PROPER MOTION OF STARS

It was

a valid point, and so a check on the proper motion of Cygnus's key

stars produced the following slow movements in any one year against

the stellar background:

The proper motion of

the principal stars of Cygnus over a period of 4,000 years, Now all this might look confusing, but what it says is that, as Robert Bauval and Graham Hancock have said in connection with the 'belt' stars of Orion, there is no significant shift in the relative positions of the stars over this time.

Only one star in Cygnus is moving faster than the rest, and this is Gienah (epsilon Cygni), which does shift slightly with respect to the Cygnus-Giza overlay, as is shown below.

The relative shift of the star Gienah (epsilon Cygni)

with respect to its

position in relation to the Third Pyramid over a period of 4,000

years As is plain to see, the shift is minimal, and does in no way change anything regarding the original proposal of the Cygnus-Giza correlation. The other two Cygnus 'wing' stars, delta Cygni, corresponding with the Great Pyramid, and Sadr (gamma Cygni), corresponding with the Second Pyramid, move so little that it is unnoticeable on a small scale map of the pyramid field.

We are, however, not leaving the matter

here. Rodney Hale and I shall continue to examine other astronomical

programs that provide the proper motion of stars, and check to see

whether they correspond with the shifts in position offered here.

The variations of pyramid positions relative to the stars of both Cygnus (in red) and Orion (in green) using four different maps

This shows the width of variations of

pyramid positions relative to the stars of both Cygnus and Orion. As we can see, there is very little difference in the positions of the pyramids from one map to the next, making no difference whatsoever to the relative positions of either the Cygnus or Orion stars when superimposed on the plateau. Without any question, the Cygnus stars align much better than those of Orion.

Once again, such ground-sky

correlations, if meaningful, might be symbolic alone, and not need

to be actual, allowing still for the possibility that the three

pyramids represent Orion and not Cygnus. However, visually Cygnus

wins hands down. Rodney Hale and I will continue to consider other

maps or photographs of the plateau with regards to the Cygnus-Giza

correlation.

These are quite clearly ridiculous observations. Not only does the well appear on the Perring map of 1837, which shows its location prior to the siting of the modern Islamic cemetery, but it also appears on the Lepsius map of 1842 (see below):

The well Beer el-Samman marked as a dot between two palm trees and two sycamore fig trees. On the left (south) we see the rock outcrop Gebel Ghibli (Arabic for 'southern hill'), and on the right the Great Sphinx.

At the left-hand base

is the end of the linear feature known as the Wall of the Crow

There seems little question that this

holy well would have played a function in Ancient Egyptian

geomythics, especially since it falls inside the plateau, being

placed as it is on the northside of the so-called Wall of the Crow,

a linear stone feature made of cyclopean blocks which dates to the

late Fourth Dynasty and is thought to be part of the plateau's

southern boundary wall.

However, it is more likely to date back to dynastic times, particularly as its accompanying sycamore is perhaps a descendent of one said to have existed in Heliopolis. It was sacred to the goddess Nut, who was occasionally shown in Ancient Egyptian art as standing in a sycamore tree pouring either water or wine from a jar on to a human-headed bird, representing the ba, or soul, of a deceased person. At its base was depicted just such a holy well, or spring.

Often Hathor replaced Nut in this scene,

showing the relationship between the two goddesses, who have much in

common.

Beer el-Samman as it appears today in the Islamic cemetery,

shaded by a sycamore

fig tree. I doubt very much whether it leads directly to a lost underworld domain, although it is interesting that the lowest level of the so-called 'Tomb of Osiris', discovered in the 1920s beneath the causeway to the Second Pyramid by Egyptologist Salim Hassan, possesses a pit thought to lead into an unexplored tunnel now beneath the present water table, this being high enough to fill the existing chamber to a depth of at least 1.5 meters.

Could the story of the holy man Hamman el-Samman guarding the entrance to an underground palace or city be the memory of real passages that permeate the living rock beneath the plateau's water line?

Conclusions

Yes, in that such superimpositions, whether involving the stars of Orion or Cygnus, put into perspective the hidden dimensions of places such as the Giza plateau. Part of me wants to dismiss the Cygnus-Giza correlation as the actions of the wily Cosmic Joker having his fun. Yet then again, if I had dismissed the correlation then I would probably never have found Beer el-Samman, or turned up the information on the strange bird catacomb beyond the northwestern edge of the plateau, which Vyse and Perring wrote contained 'bird mummies', as well as 'part of a large bird '.

Thus in conclusion, I consider that the

Cygnus-Giza correlation has not hindered my investigations on the

plateau in the least. In fact, it has given it an entirely new

dimension that I now intend exploring to its fullest.

|