|

by

Michael A. Cremo

2000

Research Associate in History and

Philosophy of Science

Bhaktivedanta Institute

Extracted from Nexus Magazine, Volume

8, Number 1

from

NexusMagazine Website

|

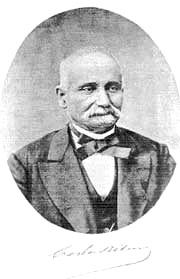

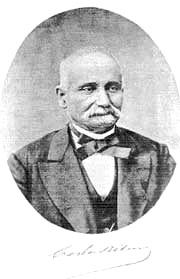

In the

1860s, Portuguese geologist Carlos Ribeiro found worked

flints in Miocene strata which suggest a much earlier

date for the emergence of modern humans than that

accepted by mainstream scientists today. |

A

CONTROVERSIAL EPISODE IN 19th-CENTURY ARCHAEOLOGY

My theoretical approach to archaeology is informed by the Puranas,

the historical writings of ancient India, which posit a human

presence extending much further back in time than most

archaeologists today are prepared to accept (Cremo, 1999). Therefore

I was intrigued when I learned of some anomalously old stone tools

discovered by Carlos Ribeiro, a Portuguese

geologist of the 19th

century. (image left) geologist of the 19th

century. (image left)

While I was going through the writings of the American geologist J.

D. Whitney (1880) who reported evidence for Tertiary human beings in

California,1 I encountered a sentence or two about

Ribeiro having

found flint implements in Miocene formations near Lisbon. The

Tertiary comprises a group of geological periods -- the Pliocene,

Miocene, Oligocene, Eocene and Palaeocene -- extending from 2

million to 65 million years ago.

The Miocene extends from 5 million

to 25 million years ago. According to current accounts, the oldest

anatomically modern humans came into existence about 100,000 to

150,000 years ago, and the oldest hominids, human ancestors, go back

about 4 million years.

Later I saw Ribeiro’s name again, this time in the 1957 edition of

Fossil Men by Boule and Vallois, who rather curtly dismissed his

work. I was led, however, by Boule and Vallois to the 1883 edition

of Le Préhistorique by Gabriel de Mortillet, who gave a favourable

report of Ribeiro’s discoveries. From de Mortillet’s bibliographic

references, I went to Ribeiro’s original reports. Using all of this

material, I wrote about Ribeiro’s discoveries and their reception in

Forbidden Archeology (Cremo and Thompson, 1993).

When I learned last year that the European Association of

Archaeologists annual meeting for the year 2000 was going to be held

in Lisbon, I proposed a paper on Ribeiro’s work for the section on

the history of archaeology. Previously I had relied only on

published records. But for my new research, I visited the Museu

Geológico in Lisbon, where I studied a collection of Ribeiro’s

artifacts. The artifacts were stored out of sight, below the display

cases featuring more conventionally acceptable artifacts from the

Portuguese Stone Ages.2 After spending a week examining and

photographing the artifacts, I went to the library of the Institute

of Geology and Mines at Alfragide to study Ribeiro’s personal

papers,3 and later I went to visit some of the sites where Ribeiro

collected his specimens.4

At the archaeology conference in Lisbon, I presented Ribeiro’s

discoveries as a case study, showing how contemporary archaeology

treats facts that no longer conform to accepted views. Keep in mind

that for most current students of archaeology, Ribeiro and his

discoveries simply do not exist. You have to go back to textbooks

printed over 40 years ago to find even a mention of him. Did Ribeiro’s work really deserve to be so thoroughly forgotten? I think

not.

A

SUMMARIZED HISTORY OF RIBEIRO’S DISCOVERIES

In 1857, Ribeiro was named to head the Geological Commission of

Portugal, and he would also be elected to the Portuguese Academy of

Sciences. In 1860, Ribeiro learned that flints bearing signs of

human work had been found in Tertiary beds between Carregado and

Alemquer, two small towns in the basin of the Tagus River, about 35

to 40 kilometers northeast of Lisbon. Ribeiro began his own

investigations, and in many localities found "flakes of worked flint

and quartzite in the interior of the beds".

Ribeiro found himself in a dilemma. The geology of the region

indicated the limestone beds were of Tertiary age, but Ribeiro

(1873a:97) felt he must submit to the then prevalent idea that

humans were not older than the Quaternary. (The Quaternary is the

most recent geological age, comprising the Pleistocene and Holocene.

It extends from two million years ago to the present.) Ribeiro

therefore assigned Quaternary ages to the implement-bearing strata (Ribeiro,

1866; Ribeiro and Delgado, 1867).

Upon seeing the maps and accompanying reports, geologists in other

countries were perplexed. The French geologist E. de Verneuil wrote

to Ribeiro on May 27, 1867, asking him to send an explanatory note;

this was read at the June 17 meeting of the Geological Society of

France and later published in the bulletin of the Society (Ribeiro,

1867). On July 16, de Verneuil wrote once more to Ribeiro, again

objecting to his placing the Portuguese formations in the Quaternary

and insisting they must be Tertiary.

During that same year, Ribeiro learned that the Abbé Louis

Bourgeois, a reputable investigator, had reported finding stone

implements in Tertiary beds in France, and that some authorities

supported him (de Mortillet, 1883:85). Under the twin influences of

de Verneuil’s criticism and the discoveries of Bourgeois, Ribeiro

began reporting that implements of human manufacture had been found

in Miocene formations in Portugal (Ribeiro, 1871, 1873a:98).

From the standpoint of modern geology, Ribeiro’s assessment of the

age of the implement-bearing formations in the Tagus River valley

near Lisbon is correct. The official geological maps of Portugal show

the formations at Ribeiro’s key sites to be Early to Middle Miocene

(Zbyszweski and Ferreira, 1966:9-11).

In 1871, Ribeiro exhibited to the members of the Portuguese Academy

of Science at Lisbon a collection of flint and quartzite implements,

including those gathered from the Tertiary formations of the Tagus

valley, and published a study on them (Ribeiro, 1871). The

implements described in this study show not only striking platforms,

bulbs of percussion and worked edges, but also signs of use.

In 1872, at the International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology

and Archaeology meeting in Brussels, Ribeiro gave another report on

his discoveries and displayed more specimens, mostly pointed flakes.

A. W. Franks, Conservator of National Antiquities and Ethnography at

the British Museum, stated that some of the specimens were the

product of intentional work.

Ribeiro’s Miocene flints made an impressive showing, but remained

controversial. At the Paris Exposition of 1878, Ribeiro displayed

specimens of Tertiary flint tools in the gallery of anthropological

science. De Mortillet visited Ribeiro’s exhibit and, in the course

of examining the specimens carefully, decided that they had

indubitable signs of human work.

De Mortillet, along with his friend and colleague Emile Cartailhac,

enthusiastically brought other archaeologists to see Ribeiro’s

specimens, and they were all of the same opinion: the flints were

definitely made by humans. Cartailhac then photographed the

specimens, and de Mortillet later presented pictures in his Musée

Préhistorique (G. and A. de Mortillet, 1881).

De Mortillet (1883:99) wrote:

"The intentional work is very well

established, not only by the general shape, which can be

deceptive, but much more conclusively by the presence of clearly

evident striking platforms and strongly developed bulbs of

percussion."

Leland W. Patterson (1983), an expert in

distinguishing artifacts from "naturefacts", believes that the bulb

of percussion is the most important sign of intentional work on a

flint flake. In addition to the striking platforms and bulbs of

percussion, some of Ribeiro’s specimens had several long vertical

flakes removed in parallel, something not likely to occur in the

course of random battering by the forces of nature.

De Mortillet (1883:99-100) further observed:

"Many of the specimens, on the same

side as the bulb of percussion, have hollows with traces and

fragments of sandstone adhering to them, a fact which

establishes their original position in the strata."

In other words, they had not slipped

into the Miocene beds in more recent times.

RIBEIRO IS

VINDICATED

At the 1880 meeting of the International Congress of Prehistoric

Anthropology and Archaeology, held in Lisbon, Portugal, Ribeiro

served as general secretary.5 Although very busy with all of the

details of organizing the event, and somewhat ill, he delivered a

report on his artifacts and displayed more specimens that were

"extracted from Miocene beds" (Ribeiro, 1884:86).

In his report ("L’homme tertiaire en Portugal"), Ribeiro (1884:88)

stated:

"The conditions in which the worked

flints were found in the beds are as follows:

(1) They were found as

integral parts of the beds themselves.

(2) They had sharp, well-preserved edges, showing

that they had not been subject to transport for any great

distance.

(3) They had a patina similar in colour to the rocks

in the strata of which they formed a part."

The second point is especially

important. Some geologists claimed that the flint implements had

been introduced into Miocene beds by the floods and torrents that

periodically washed over this terrain. According to this view,

Quaternary flint implements may have entered into the interior of

the Miocene beds through fissures and been cemented there, acquiring

over a long period of time the coloration of the beds (de Quatrefages, 1884:95). But if the flints had been subjected to such

transport, then the sharp edges would most probably have been

damaged, and this was not the case.

The Congress assigned a special commission of scientists the task of

directly inspecting the implements and the sites from which they had

been gathered. On September 22, 1880, at six in the morning, the

commission members boarded a special train and proceeded north from

Lisbon, getting off at Carregado. They proceeded further north to

Otta, and two kilometers northeast from Otta arrived at the southern

slopes of the hill called Monte Redondo. At that point, the

scientists dispersed into various ravines in search of flints.6

Paul Choffat (1884a:63), secretary of the commission, later reported

to the Congress:

"Of the many flint flakes and apparent cores taken

from the midst of the strata under the eyes of the commission

members, one was judged as leaving no doubt about the intentional

character of the work."

This was the specimen found in situ by

Bellucci. Choffat then noted that Bellucci had found on the surface

other flints with incontestable signs of work. They appeared to be

Miocene implements that had been removed from the Miocene

conglomerates by atmospheric agencies.

De Mortillet (1883:102) gave an informative account of the excursion

to Otta and Bellucci’s remarkable discovery:

"The members of the Congress arrived

at Otta, in the middle of a great freshwater formation. It was

the bottom of an ancient lake, with sand and clay in the centre

and sand and rocks on the edges. It is on the shores that

intelligent beings would have left their tools, and it is on the

shores of the lake that once bathed Monte Redondo that the

search was made. It was crowned with success.

"The able investigator of Umbria, Mr Bellucci, discovered in

situ a flint bearing incontestable signs of intentional work.

Before detaching it, he showed it to a number of his colleagues.

The flint was strongly encased in the rock. He had to use a

hammer to extract it. It is definitely of the same age as the

deposit. Instead of lying flat on a surface onto which it could

have been secondarily re-cemented at a much later date, it was

found firmly in place on the underside of a ledge extending over

a region removed by erosion. It is impossible to desire a more

complete demonstration attesting to a flint’s position in its

strata."

Study of the fauna and flora in the

region around the Monte Redondo site showed that the formations

present there can be assigned to the Tortonian stage of the Late

Miocene period (de Mortillet, 1883:102). Some modern authorities

consider the Otta conglomerates to be from the Burdigalian stage of

the Early Miocene (Antunes et al., 1980:139). After the excursion,

the commission members discussed Ribeiro’s artifacts and came to a

conclusion that was generally favourable to the authenticity of the

discoveries (Choffat, 1884b:92-93).

Altogether, there seems little reason why Ribeiro’s discoveries

should not be receiving some serious attention, even today. Here we

have a professional geologist, the head of Portugal’s Geological

Commission, making discoveries of flint implements in Miocene

strata. The implements resembled accepted types, and they displayed

characteristics that modern experts in lithic technology accept as

signs of human manufacture. To resolve controversial questions, a

congress of Europe’s leading archaeologists and anthropologists

deputed a committee to conduct a first-hand investigation of one of

the sites of Ribeiro’s discoveries. There, a scientist discovered in

situ an implement in a Miocene bed, as witnessed by several other

members of the committee.

RIBEIRO’S

FINDINGS ENTER SCIENTIFIC OBLIVION

Carlos Ribeiro died in 1882. In 1889, his colleague Joaquim Fillipe

Nery Delgado conducted some new explorations at Monte Redondo.

Delgado recovered some artifacts, which he displayed at the 10th

International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology.

No artifacts bearing signs of human work were found in excavations

he conducted. Delgado (1889:530) therefore declared he had not been

able to duplicate Ribeiro’s discoveries of worked flints in solid

rock. But Delgado did see signs of human work on the flints found

loose on the ground (1889:530). He said that many of these,

"are incontestably Tertiary and have

been naturally separated from the underlying beds solely by the

action of atmospheric agencies" (1889:529).

In the discussion that followed

Delgado’s talk, de Mortillet said he did not think Delgado’s failure

to find worked flints in his four excavations was all that

significant. He pointed out that even in places very rich in

artifacts, such as Chelles and St Acheul in France, one could go

through many cubic meters of sediment without finding any flints

showing signs of work (Delgado, 1889:532).

In 1905, in a memorial volume dedicated to Ribeiro, Delgado further

distanced himself from the conclusions of his departed colleague

(1905:33-34). Influenced by the discovery of Pithecanthropus erectus

in Java in the 1890s, he cast doubt on the discoveries of Ribeiro.

Pithecanthropus, an ape man, had been found without any stone tools

in a formation that scientists considered to be from the very latest

part of the Tertiary. Delgado implied that this ruled out the

existence of humans like us in the Tertiary, anywhere in the world.

He also implied that Pithecanthropus made it unlikely that similar

precursors to modern humans would be found in the European Tertiary.

South-East Asia, apparently, would be the place to look.

In 1942, Henri Breuil and G. Zbyszewski of the

Geological Service of

Portugal restudied the artifacts collected by Ribeiro. They

suggested that some of them did not actually display any signs of

intentional human work. And, not accepting the Tertiary age of the

rest, they reclassified them as corresponding to accepted

Pleistocene and Holocene industries, such as the Clactonian,

Tayencian, Levalloisian, Mousterian, Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic

and Neo-Eneolithic (Zbyszewski and Ferreira, 1966:85-86; Breuil and

Zbyszewski, 1942).

Here is one example of such reclassification. Ribeiro (1871:14)

described an implement of light-brown flint. It was one of several

extracted from the Lower Miocene beds forming the hill called

Murganheira. The implement from the Miocene beds at Murganheira has

worked edges, two of them joining to form a point. The point shows

signs of use. On the tool itself is written "15.IV.1869 1.5 km N da

Bemposta", indicating the artifact was found on April 15, 1869, 1.5

kilometers north of Bemposta, a locality just south of the

Murganheira hill.

On the new label prepared by the

Geological Service of Portugal during the period of

reclassification, the artifact is identified as an Upper Palaeolithic flint implement found by Ribeiro at Murganheira, near

Alemquer. Apparently there was no disputing the artifactual nature

of the object, but its age was assigned on the basis of its form

rather than its geological provenance. The Upper Palaeolithic refers

to a time in the later Pleistocene when humans of modern type were

making stone tools of relatively advanced type.

Some time after this reclassification of Ribeiro’s collection, the

artifacts were removed from display at the Museo Geológico in

Lisbon. Ribeiro and his artifacts entered into an oblivion from

which they have yet to emerge.

A

CONFLICT OF FACT AND THEORY

The history Carlos Ribeiro’s discoveries demonstrates the complex

interpretative interplay between geology and archaeology and

evolutionary theories. In the 19th century, even though most

European archaeologists were working within an evolutionary

framework, the time dimension of the evolutionary process had not

been settled, mainly because of the lack of skeletal evidence in

appropriate geological contexts. The looseness of the evolutionary

framework therefore allowed archaeologists to contemplate the

existence of Tertiary humans.

That changed in the very last decade of the 19th century. With the

discovery of Pithecanthropus erectus,

Darwinists began to solidify

an evolutionary progression that led from Pithecanthropus, at the Plio-Pleistocene boundary, to anatomically modern humans in the Late

Pleistocene. This left no room for Tertiary humans anywhere in the

world, and put the spotlight on South-East Asia as the place to look

for Tertiary precursors to Pithecanthropus. Ribeiro’s discoveries

lost their relevance and gradually disappeared from the discourse on

human origins.7

A century later, things have changed somewhat. Africa is now

generally recognised as the place where hominids first arose. For

some time, the earliest tools were thought to date back only to the

Early Pleistocene. But in recent years, archaeologists are once more

pushing the onset of stone toolmaking well into the Tertiary.

Oldowan tools have been found in the Pliocene at Gona, Ethiopia (Semaw

et al., 1997). The tools, found in large numbers and described as

surprisingly sophisticated, are about 2.5-2.6 million years old.

Therefore, we should expect to find stone tools going back even

further into the Tertiary.

Conventional candidates for the Tertiary toolmakers include the

earliest Homo or one of the australopithecines (Steele, 1999:25).

But there are other possibilities. Footprints described as

anatomically modern occur in Pliocene volcanic ash, 3.7 million

years old, at Laetoli, Tanzania (M. Leakey, 1979).8 There is even

evidence putting toolmakers close to the Iberian Peninsula, in

Morocco, in the Late Tertiary (Onoratini et al., 1990). At the Ben

Souda quarry near Fez, stone tools were found in place in the

Saissian formation which had long been considered Pliocene.

Noting the similarity of the Ben Souda

tools to the Acheulean tools from a Middle Pleistocene formation at Cuvette de Sidi Abderrahman in the area of Casablanca,

Onoratini et

al. (1990:330) decided to characterize the part of the Saissian

formation containing the tools at Ben Souda as also being Middle

Pleistocene (repeating the early mistake of Ribeiro!). Another

possibility that deserves to be considered is that there are tools

of Acheulean type in the Tertiary of Morocco.

It may be noted that anatomically modern human skeletal remains have

been found in the Tertiary (Pliocene) of Italy at Castenedolo (Ragazzoni,

1880; Sergi, 1884; Cremo and Thompson, 1993:422-432) and at

Savona

(de Mortillet, 1883:70; Issel, 1868; Cremo and Thompson,

1993:433-435). There may therefore be some reason, once more, to

consider the possibility of Tertiary industries in Portugal.

Such a possibility is not much in favour today, as can be seen in a

recent critical survey of evidence for the earliest human occupation

of Europe (Roebroeks and Van Kolfschoten, 1995). The basic thrust of

the book, which is a collection of papers presented at a conference

on the earliest occupation of Europe (held at Tautavel, France, in

1993), is to endorse a short chronology, with solid evidence for

first occupation occurring in the Middle Pleistocene at around

500,000 years.

Other discoveries favouring a long

chronology, perhaps extending into the earliest Pleistocene (1.8 to

2 million years) are mentioned, although the consensus among the

authors of the Tautavel papers is that such evidence is highly

questionable. The sites and the artifacts are nevertheless

mentioned, and are not entirely dismissed. The editors and authors

of individual chapters simply say that, in many cases, better

confirmation of the age of the site and the intentional manufacture

of the artifacts is required.

Given this liberal approach, Ribeiro’s artifacts should have been

mentioned in the chapter on the Iberian Peninsula (Raposo and

Santonja, 1995). In that chapter, the authors give the impression

that the oldest reported stone tool industries in Portugal are Early

Pleistocene pebble industries, documented by Breuil and Zbyszewski

(1942-1945). Raposo and Santonja (1995:13) called into question the

dating of the pebble tool sites, concluding that they "do not

document beyond doubt any Early Pleistocene human occupation".

But the main point is this: although the

industries reported by Breuil and Zbyszewski were not accepted, they

were at least acknowledged. The same is true of other controversial

sites indicating a possible Early Pleistocene occupation elsewhere

in the Iberian Peninsula. Raposo and Santonja did not accept them,

but they acknowledged their existence, thus offering current

archaeologists the option of conducting further research to

establish more firmly either the dates of the sites or the

artifactual nature of the stone objects found there. Ribeiro’s

discoveries deserve similar treatment.

One possible objection is that although there is some reason to

believe in a possible Early Pleistocene occupation or even a very

late Pliocene occupation of Europe, there is no reason to support a

Miocene habitation. But there is a body of evidence that can provide

a context in which the Miocene discoveries of Ribeiro might make

some sense.

Miocene flint tools are reported from Puy de Boudieu, near Aurillac,

in the department of Cantal in the Massif Central region of France (Verworn,

1905). The flint implements were found in layers of fluviatile

sands, stones and eroded chalk, along with fossils of a typical

Miocene fauna, including Dinotherium giganteum, Mastodon longirostris,

Rhinocerus schleiermacheri and Hipparion gracile. The

implement-bearing layers were covered with basalt flows (Verworn,

1905:17).

Verworn was very cautious in identifying the objects he found as

objects manufactured by humans. Summarizing his methodology, Verworn

(1905:29) said:

"Suppose I find in an interglacial

stone bed a flint that bears a clear bulb of percussion, but no

other symptoms of intentional work. In that case, I would be

doubtful as to whether or not I had before me an object of human

manufacture. But suppose I find there a flint which on one side

shows all the typical signs of percussion, and which on the

other side shows the negative impressions of two, three, four or

more flakes removed by blows in the same direction. Furthermore,

let us suppose one edge of the piece shows numerous successive

small parallel flakes removed, all running in the same

direction, and all, without exception, located on the same side

of the edge. Let us suppose that all the other edges are sharp,

without a trace of impact or rolling. Then I can say with

complete certainty: it is an implement of human manufacture."

Verworn found about 200 specimens

satisfying these criteria, and some of these also showed use-marks

on the working edges.

Similar discoveries come from various places around the world. They

include:

-

stone tools from the Miocene of Burma (Noetling, 1894)

-

stone tools and artistically carved animal bone from the Miocene of

Turkey (Calvert, 1874)

-

incised and carved animal bones from the

Miocene of Europe (Garrigou and Filhol, 1868; von Dücker, 1873)

-

stone tools from the Miocene of Europe (Bourgeois, 1873)

-

stone

tools and human skeletal remains from the Miocene of California

(Whitney, 1880)

-

a human skeleton from the Miocene of France (de Mortillet, 1883:72)

For an extensive review of such evidence from

all periods of the Tertiary, from all parts of the world, see Cremo

and Thompson (1993).

Much of this evidence, like Ribeiro’s evidence, disappeared from

active consideration by archaeologists because of their commitment

to a human evolutionary progression anchored on Pithecanthropus

erectus - mouse on right image (Cremo, forthcoming).

For example, the influential anthropologist William H. Holmes

(1899:424), of the Smithsonian Institution, rejected the California

gold mine discoveries reported by J. D. Whitney by saying:

"Perhaps

if Professor Whitney had fully appreciated the story of human

evolution as it is understood today, he would have hesitated to

announce the conclusions formulated, notwithstanding the imposing

array of testimony with which he was confronted."

Holmes (1899:470) specifically appealed the Java Man discovery,

suggesting that Whitney’s evidence should be rejected because,

"it

implies a human race older by at least one half than Pithecanthropus

erectus of Dubois, which may be regarded as an incipient form of

human only".

Not all of the evidence for Tertiary Homo comes from the 19th

century. K. N. Prasad (1982:101), of the Geological Survey of India,

described,

"a crude unifacial hand-axe pebble

tool recovered from the Late Miocene-Pliocene (9-10 m.y. BP) at

Haritalyangar, Himachal Pradesh, India".

He added (1982:102):

"The implement was recovered in

situ, during remeasuring of the geological succession to assess

the thickness of the beds. Care was taken to confirm the exact

provenance of the material, in order to rule out the possibility

of its derivation from younger horizons."

Describing the tool itself, Prasad said

(1982:102):

"The quartz artifact, heart-shaped

(90 x 70 mm), was obviously fabricated from a rolled pebble, the

dorsal side of which shows rough flaking... On the ventral side,

much of the marginal cortex is present at the distal end. Crude

flaking has been attempted for fashioning a cutting edge.

Marginal flaking at the lateral edge on the ventral side is

visible."

Prasad concluded (1982:103):

"It is not impossible that

fashioning tools commenced even as early as the later Miocene

and evolved in a time-stratigraphic period embracing the

Astian-Villafranchian."

RESURRECTING

RIBEIRO

The discoveries of Ribeiro, and other evidences for Tertiary man

uncovered by European archaeologists and geologists, are today

attributed (if they are discussed at all) to the inevitable mistakes

of untutored members of a young discipline.

Another possible explanation is that some of the discoveries are

genuine, and were filtered out of the normal discourse of a

community of archaeologists that had adopted, perhaps prematurely,

an evolutionary paradigm that placed the origins of stone toolmaking

in the Pleistocene.

But as the time-line of human toolmaking begins once more to reach

back into the Tertiary, perhaps we should withhold final

judgment

on Ribeiro’s discoveries. A piece of the archaeological puzzle that

does not fit the consensus picture at a particular moment may find a

place as the nature of the whole picture changes.

As an historian of archaeology, I believe that the discoveries of

Ribeiro remain worthy of being considered in discussions of the

earliest human occupation of Europe. I am pleased that the Museo

Geológico in Lisbon is once more considering exhibiting the

artifacts. I also encourage new investigations at Monte Redondo

and other sites identified by Ribeiro.

Endnotes:

1. Whitney was a prominent

geologist, and his reports on the discoveries were published by

the Harvard University Museum of Comparative Zoology. The

discoveries included anatomically modern human skeletal remains

and stone artifacts, such as mortars and pestles and obsidian

spear-points. They were found in gold mining tunnels that

reached Eocene river channels, sealed under hundreds of feet of

Miocene and Pliocene basalt flows in the Sierra Nevada

mountains, at places such as Table Mountain in Tuolumne County,

California. See Cremo and Thompson (1993:370-393, 439-452) for a

review and discussion.

2. The Museu Geológico is located on the second floor of

the 17th-century building in the historic centre of Lisbon that

also houses the Academia Real das Ciências de Lisboa. I was able

to match artifacts in the museum collection to 21 of the 128

drawings of artifacts shown in Ribeiro’s principal publication

on them (Ribeiro, 1871). Artifacts were matched to figures 13,

15, 16, 26, 27, 29, 36, 36b, 43, 45, 46, 55, 62, 63, 64, 73, 74,

77, 80, 82, 94. Assuming that all the artifacts figured in

Ribeiro’s 1871 publication were originally in the collection, it

appears that most are now misplaced or otherwise missing.

3. The Instituto Geológico e Mineiro is located in

Alfragide, in the newer western suburbs of Lisbon. The library

of the Museu Geológico was transferred there from central Lisbon

a few years ago.

4. The main guide to the localities I visited was

Ribeiro’s 1866 publication. The localities that I found, with

considerable help from Portuguese friends who served as drivers

and translators, were:

(1) A site at the base of

an escarpment that runs along the north side of the road

that goes from Carregado to Cadafaes (Ribeiro, 1866:28). The

site is about half the distance between Carregado and

Cadafaes (now spelled Cadafais), and can be reached by a

small dirt road going through some vineyards.

(2) Quinta de Cesar in

Carregado (Ribeiro, 1866:32).

(3) The hill called

Murganheira, east of Alemquer (Ribeiro, 1866:34).

(4) Encosta da Gorda,

near the eastern side of the Murganheira hill (Ribeiro,

1866:34).

(5) The site on the right

bank of the River Otta, where it passes the village of Otta

(Ribeiro, 1866:42).

(6) Monte Redondo, about

two kilometres northeast of Otta (Ribeiro, 1866:45).

5. The Congress was held in

the ornate main hall of the library in the building housing the

Academia Real das Ciências, located on the floor below the Museu

Geológico. The hall, still there today, is worth a visit.

6. In July 2000, I retraced the commission’s route. There

is a road leading east from Otta to Aveiras de Cima. Just as

this road leaves Otta, one turns onto a small dirt road leading

north and, following it, one eventually comes to Monte Redondo.

Monte Redondo and the surrounding area remain in a natural

condition, undisturbed by any construction. Although I suspect

the landscape has changed somewhat, ravines on the southern

slopes of Monte Redondo, like those described in the report of

the conference expedition, are still visible. Their profiles

resemble the one figured by de Mortillet (1883:101).

7. In the Pithecanthropus erectus discovery, Dubois

associated a femur with a skullcap. Considering the historical

impact of Pithecanthropus on consideration of evidence for

Tertiary humans, it is noteworthy that modern researchers no

longer consider the association genuine. When Day and Molleson

(1973) carefully re-examined the femur, they found it not

different from anatomically modern human femurs and distinct

from all other erectus femurs.

8. Leakey herself (1979:453) said the prints were exactly

like anatomically modern human footprints -- a judgment shared

by some physical anthropologists (Tuttle, 1981:91, 1987:517).

Tim White said, "Make no mistake about it. They are like modern

human footprints" (Johanson and Edey, 1981:250).

References:

-

Antunes, M.T., M.P. Ferreira, R.B.

Rocha, A.F. Soares and G. Zbyszewski, 1980. Portugal: cycle

alpin. In J. Delecourt (ed.), Géologie des Pays Européens

3:103-149. Paris: Bordas.

-

Boule, M. and H.V. Vallois, 1957.

Fossil Men. London: Thames & Hudson.

-

Bourgeois, L., 1873. Sur les silex

considérés comme portant les margues d’un travail humain et

découverts dans le terrain miocène de Thenay. Congrès

International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques,

Bruxelles, 1872, Compte Rendu: 81-92.

-

Breuil, H. and G. Zbyszewski

(1942-1945). Contribution á l’étude des industries

paléolithiques du Portugal et de leurs rapports avec la géologie

du Quaternarie. Vol. I, Les principaux gisements des deux rives

de l’ancien estuaire du Tage. Communicaçöes dos Serviços

Geológicos de Portugal: 23, 26.

-

Calvert, F.,1874. On the probable

existence of man during the Miocene period. Journal of the Royal

Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 3:127.

-

Choffat, P., 1884a. Excursion à Otta.

Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie

Préhistoriques, Lisbon, 1880, Compte Rendu: 61-67.

-

Choffat, P., 1884b. Conclusions de

la commission chargée de l’examen des silex trouvés à Otta.

Followed by discussion. Congrès International d’Anthropologie et

d’Archéologie Préhistoriques, Lisbon, 1880, Compte Rendu:

92-118.

-

Cremo, M.A., 1999. Puranic time and

the archaeological record. In T. Murray (ed.), Time and

Archaeology 38-48. London: Routledge.

-

Cremo, M.A., forthcoming. Forbidden

archeology of the Paleolithic: how Pithecanthropus influenced

the treatment of evidence for extreme human antiquity. In A.

Martins (ed.), Proceedings of the History of Archaeology

Section. European Association of Archaeologists 1999 Annual

Meeting, Bournemouth, England. Oxford: British Archaeological

Reports.

-

Cremo, M.A. and R L. Thompson, 1993.

Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race. San

Diego: Bhaktivedanta Institute.

-

Day, M.H. and T.I. Molleson, 1973.

The Trinil femora. Symposia of the Society for the Study of

Human Biology 2:127-154.

-

Delgado, J.F. Nery, 1889. Les silex

tertiaires d’Otta. Congrès International d’Anthropologie et

d’Archéologie Préhistoriques, Dixième Session, 1889, Compte

Rendu: 529-533.

-

Delgado, J.F. Nery, 1905. Elogio

Historico do General Carlos Ribeiro. Associação dos Engenheiros

Civis Portuguezes. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional.

-

De Mortillet, G., 1883. Le

Préhistorique. Paris: C. Reinwald.

-

De Mortillet, G. and A. Demortillet,

1881. Musée Préhistorique. Paris: C. Reinwald.

-

De Quatrefages, A., 1884. Hommes

Fossiles et Hommes Sauvages. Paris: B. Baillière.

-

Garrigou, F. and H. Filhol, 1868. M.

Garrigou prie l’Académie de vouloir bien ouvrir un pli cacheté,

déposé au nom de M. Filhol fils et au sien, le 16 mai 1864.

Compte Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences 66:819-820.

-

Holmes, W.H., 1899. Review of the

evidence relating to auriferous gravel man in California. In

Smithsonian Institution Annual Report 1898-1899: 419-472.

Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

-

Issel, A., 1868. Résumé des

recherches concernant l’ancienneté de l’homme en Ligurie.

Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie

Préhistoriques, Paris, 1867, Compte Rendu: 75-89.

-

Johanson, D. and M.A. Edey, 1981.

Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind. New York: Simon & Schuster.

-

Leakey, M.D., 1979. Footprints in

the ashes of time. National Geographic 155:446-457.

-

Noetling, F., 1894. On the

occurrence of chipped flints in the Upper Miocene of Burma.

Records of the Geological Survey of India 27:101-103.

-

Onoratini, G., M. Ahmanou, A.

Defleur and J.C. Plaziat, 1990. Découverte, près de Fès (Maroc),

d’une industrie Acheuléense au sommet des calcaires (Saïssiens)

réputés Pliocènes. L’Anthropologie 94(2)321-334.

-

Patterson, L.W., 1983. Criteria for

determining the attributes of man-made lithics. Journal of Field

Archaeology 10:297-307.

-

Patterson, L.W., L.V. Hoffman, R.M.

Higginbotham and R.D. Simpson, 1987. Analysis of lithic flakes

at the Calico site, California. Journal of Field Archaeology

14:91-106.

-

Prasad, K.N., 1982. Was Ramapithecus

a tool-user? Journal of Human Evolution 11:101-104.

-

Ragazzoni, G., 1880. La collina di

Castenedolo, solto il rapporto antropologico, geologico ed

agronomico. Commentari dell’Ateneo di Brescia April 4:120-128.

-

Raposo, L. and M. Santonja, 1995.

The earliest occupation of Europe: the Iberian Peninsula. In W.

Roebroeks and T. Van Kolfschoten (eds), The Earliest Occupation

of Europe. Proceedings of the European Science Foundation

Workshop at Tautavel (France), 1993. Analecta Praehistorica

Leidensia 27:7-25. Leiden: University of Leiden.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1865. Relatorio da

Commissão Geologica de Portugal, Correspondente ao Anno

Economico de 1864-65. Serviço Geológico Relatorios Annos Desde

1857-ate ao Fin do Anno Economico de 1864-1865. Instituto

Geológico e Mineiro. Núcleo de Biblioteca e Publicaçoes, Lisbon.

Arquivo Historico. Armario 1, Prataleira 2, Maço 9,

Correspendência de Carlos Ribeiro, Pasta 6.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1866. Descripção do

Terreno Quaternario das Bacias dos Rios Tejos e Sado. Com a

Versão Franceza por M. Dalhunty. Lisbon: Typographia da Academia

Real das Sciencias.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1867. Note sur le

terrain quaternaire du Portugal. Bulletin de la Société

Géologique de France 24:692, 2nd series.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1871. Description de

quelques Silex et Quartzites Taillés Provenant des Couches du

Terrain Tertiaire et du Quaternaire des Bassins du Tage et du

Sado. Lisbon: Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1873a. Sur des silex

taillés, découverts dans les terrains miocène du Portugal.

Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie

Préhistoriques, Bruxelles, 1872, Compte Rendu: 95-100.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1873b. Sur la position

géologique des couches miocènes et pliocènes du Portugal qui

contiennent des silex taillés. Congrès International

d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques, Bruxelles,

1872, Compte Rendu 100-104.

-

Ribeiro, C., 1884. L’homme tertiaire

en Portugal. Congrès International d’Anthropologie et

d’Archéologie Préhistoriques, Lisbon, 1880, Compte Rendu: 81-91.

-

Ribeiro, C. and J.F. Nery Delgado,

1867. Carta Geologica de Portugal na Escala 1:500000.

-

Ribeiro, C. and J.F. Nery Delgado,

1876. Carta Geologica de Portugal na Escala 1:500000.

-

Roebroeks, W. and T. Van Kolfschoten

(eds), 1995. The Earliest Occupation of Europe. Proceedings of

the European Science Foundation Workshop at Tautavel (France),

1993, Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 27. Leiden: University of

Leiden.

-

Sankhyan, A.R., 1981. First evidence

of early man from Haritalyangar area, Himalchal Pradesh. Science

and Culture 47:358-359.

-

S. Semaw, P. Renne, J.W.K. Harris,

C.S. Feibel, R.L. Bernor, N. Fesseha and K. Mowbray, 1997.

2.5-million-year-old stone tools from Gona, Ethiopia. Nature

385:333-336.

-

Steele, J., 1999. Stone legacy of

skilled hands. Nature 399:24-25.

-

Verworn, M., 1905. Die

archaeolithische Cultur in den Hipparionschichten von Aurillac (Cantal).

Abhandlungen der königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu

Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse, Neue Folge

4(4):3-60.

-

Von Dücker, Baron, 1873. Sur la

cassure artificelle d’ossements recuellis dans le terrain

miocène de Pikermi. Congrès International d’Anthropologie et

d’Archéologie Préhistoriques, Bruxelles, 1872, Compte Rendu:

104-107.

Whitney, J.D., 1880. The auriferous gravels of the Sierra Nevada

of California. Harvard University, Museum of Comparative Zoology

Memoir 6(1).

-

Zbyszewski, G. and O. da Veiga

Ferreira, 1966. Carta Geológica de Portugal Na Escala 1/50,000.

Notícia Explicativa da Folha 30-B Bombarral. Lisbon: Serviço

Geológicos de Portugal. See also the actual map, published

separately.

|

geologist of the 19th

century. (image left)

geologist of the 19th

century. (image left)