|

by Eric Jaffe

Grant, no longer a kid in stature if

still in spirit, now plays a substantial role in setting those odds.

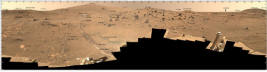

The geologist at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, part of

the National Air and Space Museum, is one of a half dozen scientists

in charge of creating itineraries for Spirit and Opportunity, the

two NASA rovers that since early 2004 have explored Mars for signs

of life, past or present.

These tasks are reserved for the Mars Science Laboratory mission, scheduled for 2010.

The search for life in the universe, however, isn't confined to the rovers' path. For that matter, it's no longer limited to Mars, or even the Earth's solar system. More and more, astronomers at labs and observatories around the world are finding evidence for the foundations of life—foremost, water—in our planet cluster and beyond.

That column received another check in

mid June, when a group of scientists revived the idea that a vast

ocean once existed on the northern hemisphere of Mars. A couple

decades ago, scientists analyzed images of this region and found

what seemed to be a shoreline. But an ocean shoreline has a uniform

elevation, and later topographical tests revealed great variation—in

some places, more than a mile separated the terrain's peaks and

dips.

Whether scientists can dig into the planet's surface and find evidence of water—and with it signatures of life—remains to be seen. Whether they can identity those signatures accurately is even another question. Still, the new work invites a fresh topic to a conversation that has focused on the rovers' images, writes Maria Zuber of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who was not associated with the study, in an accompanying commentary.

Many scientists believe that the blue

history of

Europa, one of Jupiter's moons, is still being written. Europa circles Jupiter every few days, and this rapid orbit

generates friction that heats up the moon's interior. For that

reason, some feel that an enormous salty ocean still exists beneath

Europa's frozen surface, containing perhaps twice as much liquid as

all the Earth's oceans combined.

Because Europa is bombarded by

radiation, Earth-like organisms could not live on the surface. But

they might exist just several feet below in visible cracks. In

recent papers and talks, Jere Lipps of the University of California,

Berkeley, has outlined several ways in which life on Europa, or its

remains, might be exposed to the surface—and likewise to rovers or

orbiters sent to study the moon. These include places where ice has

cracked and refrozen with life trapped inside; blocks of ice that

have broken off, flipped over and now face the surface; and debris

lodged in ridges or deep crevices.

While Europa and other sites near Earth,

such as Saturn's moon Titan, remain promising places to find water,

some scientists have set their sights far beyond this solar system.

Recently, Travis Barman of Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona,

detected water in the atmosphere of a planet some 150 light years

away—the first such evidence for a planet outside Earth's cluster.

An artist's impression shows an extended ellipsoidal envelope of oxygen and carbon discovered around the extrasolar planet HD 209458b. Credit: European Space Agency and Alfred Vidal-Madjar (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS, France)

A couple weeks later, a team of European researchers announced

another breakthrough outside this solar system: the discovery of a

planet incredibly similar to Earth. The planet, some 20 light years

away and five times the mass of Earth, circles the star Gliese 581.

Several years ago, scientists found another planet—this one similar

to Venus—orbiting this same star.

In the end, though, watery conditions, or even water itself, can only tell so much of the story of life beyond Earth. The conclusion must wait until more powerful tools or more precise explorations turn mere suggestion into solid proof.

|