|

MOST OF THE INFORMATION HERE TAKEN

FROM: from PowerOfTheShaman Website

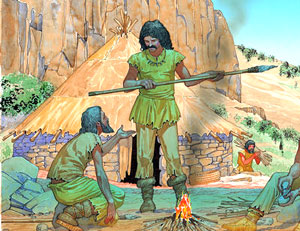

The image above shows an impression of a room called the 'Vulture Shrine' in the town of Çatal Hüyük, an ancient site still being excavated at Anatolia, Turkey.

Çatal Hüyük culture dates back to 6,500 BCE and yet these people were surprisingly sophisticated. The vulture image appears to represent for them a god-form, responsible for removing the head (i.e. the soul?) of the deceased, as can be seen in the picture above. They may have practiced 'sky-burials' (where corpses are left to the birds to eat) or the imagery may have been entirely metaphorical, or both. There is some evidence to suggest that over time as this culture developed the bird image evolved into that of a 'vulture-goddess'. But most importantly at least one of the murals from Çatal Hüyük apparently shows a human being dressed in a vulture skin.

In the 1950's the archaeologist/anthropologists Rose Solecki and her husband Ralph began excavating a cave site near the Greater Zab river in Kurdistan. This cave had been used for burials by the Zawi Chemi people (as this small area is called) around 8870 BC (plus or minus 300 years, according to carbon-dating) -- over 10,000 years ago -- and 4,000 years before the beginnings of the various Mesopotamia cultures referred to here. What did they discover that was so significant?

They found a number of goat skulls

placed next to the wing bones of large predatory birds, including

the bearded vulture, the griffon vulture, the white-tailed sea eagle

and the great bustard. The Soleckis had to ask themselves what the

purpose of such a 'ritual burial' was, and why it was that only

certain species of birds had been selected.

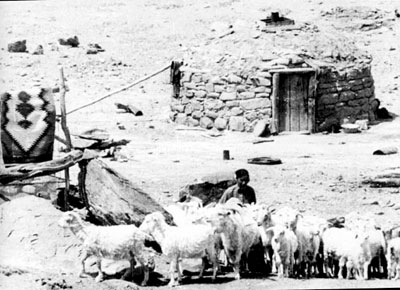

Around 11,000 years ago at Zawi Chemi in the Zagros Mountains, people used river boulders to build some of the earliest houses.

Remains of a Navajo rock hogan similar in construction Zawi Chemi stone houses. Located in Monument Valley, U.S. desert southwest.

Note door as well as

possibility of

same type roof construction.

An inhabited modern

day Navajo stone hogan. In 1977 the journal Sumer published an article by Rose Solecki entitled 'Predatory Bird Rituals at Zawi Chemi Shanidar' where she described the findings, going on to suggest that the wings had almost certainly been utilized as part of some kind of ritualistic costume, worn either for personal decoration or for ceremonial purposes.

She connected the finds with the Vulture Shamanism of the protoneolithic Çatal Hüyük community in Central Anatolia mentioned above (which was 2000 years later in time, and several hundred miles away in distance). Recognizing the importance of their discovery, however, Rose Solecki concluded the article by saying:

The ritual coats of present-day Siberian Shamans are cut to look like birds: they are cut to a point and tasselled in a way that is suggestive of feathers, and this is quite deliberate. And, although in all the forms of Shamanism across Asia there is little interest in creating any long-lasting images of winged humans, the notion of the Shaman being able to fly is nonetheless universal.

When stone-carved motifs do start to appear around 3,000 BC in Mesopotamia and the surrounding area, the wings of these winged beings seem to signify an ability to travel to places that ordinary people can't reach, along with an ability to 'mediate' between the human world and some other 'higher' state or states. Both of these qualities are (also) universally considered to be the main attributes of a Shaman.

Undoubtedly this also helps explain why

Shamen across the world generally tend to have a strong connection

with birds. The Shaman can 'fly' in trance, travelling to the realm

of the spirits where he can then either do battle against malign

entities, or try and persuade, flatter, cajole or otherwise entreat

the spirits to act for the benefit of one or more human beings.

Although it is not known what mural or murals the author of the above article is specifically referring to, the sketches below accompanied a 1984 article by James Mellaart, "Some Notes on the Prehistory of Anatolian Kilims." (B. Frauenknecht, Early Turkish Tapestries, pp. 25-41.) show what appears to be "a human figure dressed in a vulture skin."

Mellaart says the majority of the motifs were copied from Çatal Hüyük wall paintings (or in the case of Numbers 67-70 from Hacilar painted pots).

Please note drawing Number 74 as well as Number 82, traced or drawn by Mellaart from the walls of actual Çatal Hüyük murals. The images seem quite clear, while other close by motifs indicate a similar human figure, vulture theme as well, albeit in a much more abstract fashion.

Vulture wings had almost certainly been utilized as part of some kind of ritualistic costume, worn either for personal decoration or for ceremonial purposes.

The Golden Purifier

The Vulture uses air currents against the pull of gravity. It does not use its own energy, but uses the energies of the Earth instead, the energies of the Earth being ONE of the mainstay sources in The Power of the Shaman. A very valuable lesson.

The scientific name for the Turkey Vulture is CATHARTES AURA which means GOLDEN PURIFIER because as it goes about it's lifetime business it purifies the landscape and environment in it's own natural way, ensuring the continued health and life of other living things.

The Vulture is a promise that all

hardship was temporary and necessary for a higher purpose. Once a

Vulture enters your life as a totem or guide, it will remain with

you for life.

One roost was observed when they had a

dead cow in their neighborhood. They somehow contacted a roost of

100 vultures about 30 miles away to come join them. Several days

later, before they finished their feast, two more cows died. Within

a day the vultures had contacted another roost to join them. At

night all the birds visited together in the same or neighboring

trees. There were now three different roosts living together. When

the cows had been cleaned up the several visiting roosts went home.

(source)

Herodorus Ponticus relates that great men of legend were always very joyful when a vulture appeared upon any action. For it is a creature the least hurtful of any, pernicious neither to corn, fruit-tree, nor cattle; it preys only upon carrion, and never kills or hurts any living thing; and as for birds, it touches not them, though they are dead, as being of its own species, whereas eagles, owls, and hawks mangle and kill their own fellow-creatures.

That very same overall innate nature

imbedded in the actions and life of the vulture, never killing or

hurting a living thing or its own fellow creatures, is reflected for

the most part, in and by the the actions and life of the person that

truly has the vulture as a totem animal.

Be as it may, the Assyrians, Greeks and

other early civilization city-states were actually late comers to

the use or representation of vultures in ritual, religious, or

shamanistic rites.

The cave had been used for burials by an ancient tribal people called the Zawi Chami around 8870 BCE (plus or minus 300 years, according to carbon-dating) --over 10,000 years ago-- which is well over 4,000 years before the beginnings of any of the various cultures mentioned above. In their dig the Soleckis found a number of wing bones of large predatory birds, which turned out to be Gyptaeus barbatus (the bearded vulture) and Gyps fulvus (the griffon vulture).

Vulture image with

headless man at Çatal Hüyük Can Göknil in Creation Myths From Central Asia To Anatolia: Images From The Creation Myths Of The Turks writes:

Each place and location has its own power and potency. By raising our consciousness about the geo-cosmic specificities of gravity, light, magnetism, solstices, equinoxes, lunar cycles, indigenous plants, animals, climate, and so forth in any given area, we can come to value the variety of diverse cultures and regions whose multiple knowledges all serve to enhance life everywhere on our planet.

Most of these geo-cosmic teachings can only be acquired in the particular region in which they occur. If we are to awaken our own Shamanic abilities, perhaps lost in the mist of time, then we must attune ourselves to precisely those same forces as they manifest themselves in our own bio-regions.

In some cases this may require us to

learn about our region from the indigenous tribes in our area; in

other cases we must set about discovering the power of the places in

which we live on our own. We need not run away to other "exotic"

cultures, but begin exploring our own backyards.

|