LIBER LXXI

HELENA PETROVNA BLAVATSKY 8°=3°

WITH A COMMENTARY BY

FRATER O.M.

7°=4

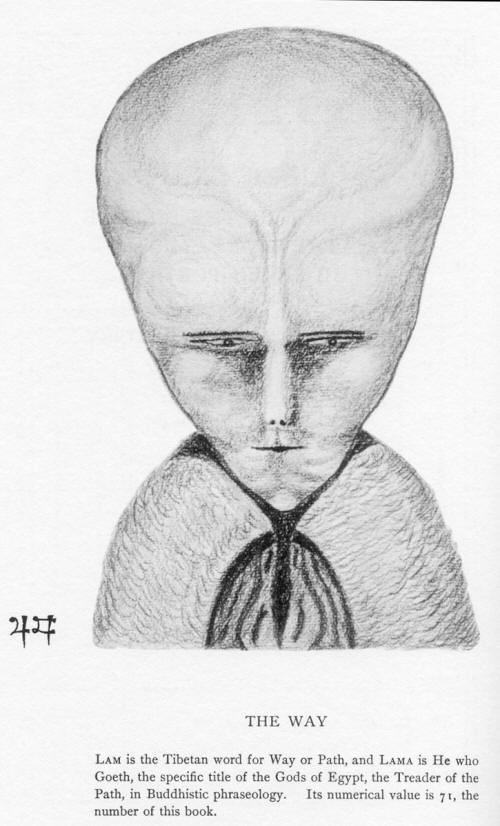

Figure 14. The

Way.

Lam is the Tibetan word for Way or Path, and Lama is He who

Goeth,

the specific title of the Gods of Egipt, the Treader of the Path,

in Buddhistic phraseology. Its numerical value is 71, the number

of

this book.

Prefatory Note

Do

what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

I

T is NOT VERY DIFFICULT to write a book, if one chance to possess the

necessary degree of Initiation, and the power of expression. It is infernally

difficult to comment on such a Book. The principal reason for this is that

every statement is true and untrue, alternately, as one advances upon the Path

of the Wise. The question always arises: For what grade is this Book meant? To

give one simple concrete example, it is stated in the third part of this

treatise that Change is the great enemy. This is all very well as meaning that

one ought to stick to one’s job. But in another sense Change is the Great

Friend. As it is marvelous well shewed forth by The Beast Himself in Liber Aleph, Love is the law, and Love

is Change, by definition. Short of writing a separate interpretation suited

for every grade, therefore, the commentator is in a bog of quandary which

makes Flanders Mud seem like polished granite. He can only do his poor best,

leaving it very much to the intelligence of each reader to get just what he

needs. These remarks are peculiarly applicable to the present treatise; for

the issues are presented in so confused a manner that one almost wonders

whether Madame Blavatsky was not a reincarnation of the Woman with the Issue

of Blood familiar to readers of the Gospels. It is astonishing and distressing

to notice how the Lanoo, no matter what happens to him, soaring aloft like the

phang, and sailing gloriously

through innumerable Gates of High Initiation, nevertheless keeps his original

Point of View, like a Bourbon. He is always getting rid of Illusions, but,

like the entourage of the Cardinal Lord Archbishop of Rheims after he

cursed the thief, nobody seems one penny the worse—or the

better.

Probably

the best way to take the whole treatise

(The

Voice of The Silence)

is to assume that it is written for

the absolute tyro, with a good deal between the lines for the more advanced

mystic. This will excuse, to the mahatma-snob, a good deal of apparent

triviality and crudity of standpoint. It is of course necessary for the

commentator to point out just those things which the novice is not expected to

see. He will have to shew mysteries in many grades, and each reader must glean

his own wheat.

At

the same time, the commentator has done a good deal to uproot some of the

tares in the mind of the tyro aforesaid, which Madame Blavatsky was apparently

content to let grow until the day of judgment. But that day is come since she

wrote this Book; the New Ćon is here, and its Word is Do what thou wilt. It is

certainly time to give the order: Chautauqua est

delenda.1

Love

is the law, love under will.

FRAGMENT

1

The

Voice of the Silence

1. These

instructions are for those ignorant of the dangers of the lower iddhi (magical

powers).

Do

what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Nothing less can satisfy than

this Motion in your orbit.

It

is important to reject any iddhi of

which you may become possessed. Firstly, because of the wasting of energy,

which should rather be concentrated on further advance; and secondly, because

iddhi are in many cases so

seductive that they lead the unwary to forget altogether the real purpose of

their endeavours.

The

Student must be prepared for temptations of the most extraordinary subtlety;

as the Scriptures of the Christians mystically put it, in their queer but

often illuminating jargon, the Devil can disguise himself as an Angel of

Light.

A

species of parenthesis is necessary thus early in this Comment. One must warn

the reader that he is going to swim in very deep waters. To begin with, it is

assumed throughout that the student is already familiar with at least the

elements of Mysticism. True, you are supposed to be ignorant of the dangers of

the lower iddhi; but there are

really quite a lot of people, even

in

Boston, who do not know that there are any iddhi at all, low or high. However,

one who has been assiduous with Book 4, by Frater Perdurabo, should have no

difficulty so far as a general comprehension of the subject-matter of the Book

is concerned. Too ruddy a cheerfulness on the part of the assiduous one will

however be premature, to say the least.

For the fact is that this treatise

does not contain an intelligible and coherent cosmogony. The unfortunate Lanoo

is in the position of a sea-captain who is furnished with the most elaborate

and detailed sailing-instructions, but is not allowed to have the

slightest idea of what port he is to make, still less given a chart of the

Ocean. One finds oneself accordingly in a sort of “Childe Roland to the Dark

Tower came” atmosphere. That poem of Browning owes much of its haunting charm

to this very circumstance, that the reader is never told who Childe Roland is,

or why he wants to get to the Dark Tower, or what he expects to find when he

does get there. There is a skillfully constructed atmosphere of Giants, and

Ogres, and Hunchbacks, and the rest of the apparatus of fairy-tales; but there

is no trace of the influence of Bćdeker in the style.

Now this is really very

irritating to anybody who happens to be seriously concerned to get to that

tower. I remember, as a boy, what misery

I

suffered over this poem. Had

Browning been alive,

I

think

I

would have sought him out, so seriously did

I

take the Quest. The student of Blavatsky is equally handicapped.

Fortunately, Book 4, Part III, comes to the rescue once more with a rough

sketch of the Universe as it is conceived by Those who know it; and a regular

investigation of that book, and the companion volumes ordered in “The

Curriculum of the A:. A:.,” fortified by steady persistence in practical

personal exploration, will enable this Voice of the Silence to become a

serious guide in some of the subtler obscurities which weigh upon the Eyelids

of the Seeker.

2. He who would hear the voice

of năda, the

“Soundless

Sound,”

and comprehend it, he has to learn the nature

of

dhărană.2

The

voice of nada is very soon heard by

the beginner, especially during the practice of pranayama (control of breath-force).

At first it resembles distant surf, though in the adept it is more like the

twittering of innumerable nightingales; but this sound is premonitory, as it

were, the veil of more distinct and articulate sounds which come later. It

corresponds in hearing to that dark veil which is seen when the eyes are

closed, although in this case a certain degree of progress is necessary before

anything at all is heard.

3. Having become indifferent

to objects of perception, the pupil must seek out the răja’ of the senses, the

Thought-Producer, he who awakes illusion.

The

word “indifferent” here implies “able to shut out.” The Rajah referred to is

in that spot whence thoughts spring. He turns out ultimately to be Mayan, the

great Magician described in the 3rd Ćthyr. 2 Let the Student notice that in

his early meditations, all his thoughts will be under the tamas-guna, the principle of

Inertia and Darkness. When he has destroyed all those, he will be under the

dominion of an entirely new set of the type of rajas-guna, the principle of Activity,

and so on.

To the advanced Student a simple ordinary thought, which seems

little or nothing to the beginner, becomes a great and terrible fountain of

iniquity, and the higher he goes, up to a certain point, the point of

definitive victory, the more that is the case. The beginner can think, “it is

ten o’clock,” and dismiss the thought. To the mind of the adept this sentence

will awaken all its possible correspondences, all the reflections he has

ever made on time, as also accidental sympathetics like Mr. Whistler’s essay;

and if he is sufficiently far advanced, all these thoughts in their hundreds

and thousands diverging from the one thought, will again converge, and become

the resultant of all those thoughts. He will get samadhi upon that original thought,

and this will be a terrible enemy to his progress.

4. The Mind is the great

Slayer of the Real.

In

the word “Mind” we should include all phenomena of Mind, including samadhi itself. Any phenomenon has

causes and produces results, and al! these things are below the “REAL.” By the

REAL is here meant the nibbanadhatu.

5.

Let

the Disciple slay the Slayer. For— This is a corollary of Verse 4. These texts

may be interpreted in a

quite

elementary sense. It is of course the object of even the beginner to suppress

mind and all its manifestations, but only as he advances will he discover what

Mind means.

6. When to himself his form

appears unreal, as do on

waking

all the forms he sees in dreams;

This

is a somewhat elementary result. Concentration on any subject leads soon

enough to a sudden and overwhelming conviction that the object is unreal.

The reason of this may perhaps be—speaking philosophically—that the object,

whatever it is, has only a relative existence.1

7. When he has ceased to hear

the many, he may discern the ONE —-the inner sound which kills the

outer.

By

the “many” are meant primarily noises which take place outside the Student,

and secondly, those which take place inside

hmm.

For

example, the pulsation of the blood in the ears, and later the mystic sounds

which are described in Verse 40.

8. Then only, not till then,

shall he forsake the region of asat,

the false, to come unto the realm of sat, the true.

By

“sat, the true,” is meant a thing

previous to the “REAL” referred to above. Sat itself is an illusion. Some

schools of philosophy have a higher asat, Not-Being, which is beyond sat, and consequently is to šivadaršana as sat is to atmadaršana.2 Nirvana is

beyond both these.

9. Before the soul can see,

the Harmony within must be

attained,

and fleshly eyes be rendered blind to all illusion.

By the “Harmony within” is meant that state in which neither

objects of sense, nor physiological sensations, nor emotions, can disturb the

concentration of thought.

10. Before the Soul can hear, the image

(man) has to

become

as deaf to roarings as to whispers, to cries of

bellowing

elephants as to the silvery buzzing of the golden

fire-fly.

In

the text the image is explained as “Man,” but it more properly refers to

the consciousness of man, which consciousness is considered as being a

reflection of the Non-Ego, or a creation of the Ego, according to the school

of philosophy to which the Student may belong.

11. Before the soul can comprehend and may

remember, she must unto the Silent Speaker be united just as the form to which

the clay is modeled, is first united with the

potter’s

mind.

Any

actual object of the senses is considered as a precipitation of an ideal. Just

as no existing triangle is a pure triangle, since it must be either

equilateral, isosceles, or scalene, so every object is a miscarriage of an

ideal. In the course of practice one concentrates upon a given thing,

rejecting this outer appearance and arriving at that ideal, which of course

will not in any way resemble any of the objects which are its incarnations. It

is with this in view that the verse tells us that the Soul must be united to

the Silent Speaker. The words “Silent Speaker” may be considered as a

hieroglyph of the same character as Logos, Adonai or the Ineffable

Name.

12. For then the soul will hear and will

remember.

The

word “hear” alludes to the tradition that hearing is the organ of Spirit, just

as seeing is that of Fire. The word “remember” might be explained as “will

attain to memory.” Memory is the link between the atoms of consciousness, for

each successive consciousness of Man is a single phenomenon, and has no

connection with any other. A looking-glass knows nothing of the different

people that look into it. It only reflects one at a time. The brain is however

more like a sensitive plate, and memory is the faculty of bringing up into

consciousness any picture required. As this occurs in the normal man with his

own experiences, so it occurs in the Adept with al! experiences. (This is one

more reason for His identifying Himself with others.)

13. And then to the inner ear will speak—

THE VOICE OF THE SILENCE

And

say:— What follows must be regarded as the device of the poet, for

of

course

the “Voice of the Silence”

cannot be interpreted in words. What follows is

only its utterance in respect of the Path itself.

14. If thy soul smiles while bathing in the

Sunlight of thy Life; if thy soul sings within her chrysalis of flesh and

matter; if thy soul weeps inside her castle of illusion; if thy soul struggles

to break the silver thread that binds her to the MASTER; know, O Disciple, thy

Soul is of the earth.

In

this verse the Student is exhorted to indifference to everything but his own

progress. It does not mean the indifference of the Man to the things around

him, as it has often been so unworthily and wickedly interpreted. The

indifference spoken of is a kind of inner indifference. Everything should be

enjoyed to the fu!!, but always with the reservation that the absence of the

thing enjoyed shall not cause regret. This is too hard for the beginner, and

in many cases it is necessary for him to abandon pleasures in order to prove

to himself that he is indifferent to them, and it may be occasionally

advisable even for the Adept to do this now and again. Of course during

periods of actual concentration there is no time whatever for anything but the

work itself; but to make even the mildest asceticism a rule of life is the

gravest of errors, except perhaps that of regarding Asceticism as a virtue.

This latter always leads to spiritual pride, and spiritual pride is the

principal quality of the brother of the Left-hand Path.

“Ascetic” comes from the Greek

“to work curiously, to

adorn, to exercise, to train. ”The Latin ars is derived from this same word.

Artist, in its finest sense of creative craftsman, is therefore the best

translation. The word has degenerated under Puntan foulness.

“to work curiously, to

adorn, to exercise, to train. ”The Latin ars is derived from this same word.

Artist, in its finest sense of creative craftsman, is therefore the best

translation. The word has degenerated under Puntan foulness.

15. When to the

World’s turmoil thy budding soul lends ear; when to the roaring voice of the

great illusion thy Soul responds; when frightened at the sight of the hot

tears of pain, when deafened by the cries of distress, thy soul withdraws like

the shy turtle within the carapace of

SELFHOOD,

learn, O Disciple, of her Silent “God,” thy Soul is an unworthy

shrine.

This

verse deals with an obstacle at a more advanced stage. It is again a warning

not to shut one’s self up in one’s own universe. It is not by the exclusion of

the Non-Ego that saintship is attained, but by its inclusion. Love is the law,

love under will.

16. When waxing stronger, thy Soul glides

forth from her secure retreat; and breaking bose from the protecting shrine,

extends her silver thread and rushes onward; when beholding her image on the

waves of Space she whispers, “This is I,” —declare, O Disciple, that thy Soul

is caught in the webs of delusion.

An

even more advanced instruction, but still connected with the question of the

Ego and the non-Ego. The phenomenon described is perhaps ătmadaršana, which is still a

delusion, in one sense still a delusion of personality; for although the Ego

is destroyed in the Universe, and the Universe in it, there is a distinct

though exceedingly subtle tendency to sum up its experience as

Ego.

These

three verses might be interpreted also as quite elementary; y. 14 as

blindness to the First Noble Truth “Everything is Sorrow”; y. 15 as the

coward’s attempt to escape Sorrow by Retreat; and y. 16 as the acceptance of

the Astral as SAT.

17. This Earth, Disciple, is the Hall of Sorrow,

wherein are set along the Path of dire probations, traps to

ensnare

thy

EGO by the delusion called “Great Heresy.” Develops still further these

remarks.

18. This earth, O ignorant Disciple, is but the

dismal

entrance

leading to the twilight that precedes the valley of true light—that light

which no wind can extinguish, that light which burns without a wick or fuel.

19. Saith the Great Law:—”In order to

become the KNOWER of ALL-SELF, thou hast

first

of

SELF to be the knower.” To reach the knowledge of that SELF, thou hast to give

up Self to Non-Self, Being to

Non-Being, and then thou canst repose between the wings of the GREAT BIRD.

Aye, sweet is rest between the wings of that which is not born, nor dies, but

is the AUM throughout eternal ages.

The

words “give up” may be explained as “yield” in its subtler or

quasi-masochistic erotic sense, but on a higher plane. In the following

quotation from the “Great Law” it explains that the yielding is not the

beginning but the end of the Path.

55.

Then

let the End awake. Long hast thou

slept, O great God Terminus! Long ages hast

thou waited at the end of the city and the

roads thereof.

Awake Thou! wait no

more!

56. Nay, Lord! but I am come to

Thee. It is I

that wait at last.

57. The prophet cried against the

mountain;

come thou hither, that I may speak with

thee!

58. The mountain stirred not.

Therefore went

the prophet unto the mountain, and spake

unto it. But the feet of the prophet were

weary, and the mountain heard not his

voice.

59. But 1 have called unto Thee, and 1 have

journeyed unto Thee, and it availed me not.

60. b waited patiently, and Thou

wast with me

from the beginning.

61. This now I know, O my beloved, and we

are stretched at our ease among the vines.

62. But these thy prophets; they must cry

aloud and scourge themselves; they must cross trackless wastes and unfathomed

oceans; to await Thee is the end, not the beginning.’

Auth

is

here quoted as the hieroglyph of the Eternal.

“A” the beginning of sound,

“u” its middle, and “m” its end,

together form a single word or Trinity, indicating that the Real must be

regarded as of this three-fold nature, Birth, Life and Death, not successive,

but one. Those who have reached trances in which “time” is no more will

understand better than others how this

may be.

20. Bestride the Bird of Life, if thou

would’st know.

The

word “know” is specially used here in a technical sense.

Avidya, ignorance, the first of the

fetters, is moreover one which includes all the others.

With

regard to this Swan Auth compare

the following verses from the “Great Law,” “Liber LXV,”

11:17—25.

17. Also the Holy One came upon me, and I

beheld a white swan floating in the blue.

18. Between its wings I sate, and the ćons

fled away.

19. Then the swan flew and dived and

soared, yet no whither we went.

20. A little crazy boy that rode with me

spake unto the swan, and said:

21. Who art thou that dost float and fly

and dive and soar in the inane? Behold, these many ćons have passed; whence

camest thou? Whither wilt thou go?

22. And laughing ˇ child him, saying: No

whence! No whither!

23. The swan being silent, he answered:

Then, if with no goal, why this eternal journey?

24. And I laid my head against the Head of

the Swan, and laughed, saying: ˇs there not joy ineffable in this aimless

winging? Is there not weariness and impatience for who would attain to some

goal?

25. And the swan was ever silent. Ah! but

we floated in the infinite Abyss. Joy! Joy!

White

swan, bear thou ever me up

between

thy wings!

21. Give up thy life, if thou would’st

live.

This verse may be compared

with similar statements in the Gospels, in

The Vision and the Voice, and in the

Books of It does not mean

asceticism in the sense usually understood by the world. The l2th Ćthyr2

gives the clearest explanation of this phrase.

22. Three Halls, O weary pilgrim, lead to the end of toils. Three Halls, O

conqueror of Mara, will bring thee through three states into

the fourth and thence into the seven worlds, the worlds of Rest

Eternal.

If this had been a genuine

document I should have taken the three states to be sirotăpanna,3 etc., and

the fourth arhat, for which the reader should consult “Science and Buddhism”4

and similar treatises. But as it is better than “genuine,” being, like

The Chemical Marriage of Christian Rosencreutz, the forgery of a great adept, one

cannot too confidently refer it thus. For the “Seven Worlds” are not

Buddhism.

23. If

thou would’st learn their names, then hearken, and

remember.

The name of the first Hall

is IGNORANCE —avidyă. It is the Hall in which thou saw’s the light, in which

thou livest and shalt die.

These

three Halls correspond to the gunas:

Ignorance, tamas; Learning,

rajas; Wisdom,

sattva.

Again,

ignorance corresponds to Malkuth and Nephesch (the animal soul), Learning to

Tiphareth and Ruach (the mi), and Wisdom to Binah and Neschamah (the

aspiration or Divine Mind).

24. The name of Hall the second is the Hall

of LEARNING. in it thy Soul will find the blossoms of life, but under every

flower a serpent coiled.

This

Hall is a very much larger region than that usually understood by the

Astral World. It would certainly include alI states up to

dhyăna. The Student will remember that

his “rewards” immediately transmute themselves into

temptations.

25.

The

name of the third Hall is Wisdom, beyond which stretch the shoreless waters of

aksara,1 the indestructible Fount

of Omniscience.

Aksara

is

the same as the Great Sea of the Qabalah. The reader must consult

The Equinox for a full study of this

Great Sea.2

26. If thou would’st cross the first Hall

safely, let not thy mind mistake the fires of lust that burn therein for the

Sunlight of life.

The

metaphor is now somewhat changed. The Hall of ignorance represents the

physical life. Note carefully the phraseology, “let not thy mind mistake the

fires of lust.” It is legitimate to warm yourself by those fires so long as

they do not deceive you.

27. If thou would’st cross the second

safely, stop not the fragrance of its stupefying blossoms to inhale. if freed

thou would’st be from the karmic

chains, seek not for thy guru

in those măyăvic

regions.

A

similar lesson is taught in this verse. Do not imagine that your early psychic

experiences are Ultimate Truth. Do not become a slave to your

results.

28. The WISE ONES tarry not in

pleasure-grounds of senses.

This

lesson is confirmed. The wise ones tarry not. That is to say, they do not

allow pleasure to interfere with business.

29. The WISE ONES heed not the

sweet-tongued voices of illusion.

The

wise ones heed not. They listen to them, but do not necessarily attach

importance to what they say.

30. Seek for him who is to give thee birth,

in the Hall of Wisdom, the Hall which lies beyond, wherein all shadows are

unknown, and where the light of truth shines with unfading

glory.

This

apparently means that the only reliable

guru is one who has attained the grade

of Magister Templi. For the attainments of this grade consult

iber 418], etc.1

31. That which is uncreate abides in thee,

Disciple, as it abides in that Hall. If thou would’st reach it and blend the

two, thou must divest thyself of thy dark garments of illusion. Stifle the

voice of flesh, albow no image of the senses to get between its light and

thine that thus the twain may blend in one. And having learnt thine own

ajńăna2, flee from the Hall of

Learning. This Hall is dangerous in its perfidious beauty, is needed but for

thy probation. Beware, Lanoo, lest dazzled by illusive radiance thy Soul

should linger and be caught in its deceptive light.

This

is a résumé of the previous seven verses. It inculcates the necessity of

unwavering aspiration, and in particular warns the advanced Student against

accepting his rewards. There is ant method of meditation in which the Student

kills thoughts as they arise by the reflection, “That’s not it.” Frater P.

indicated the same by taking as his motto, in the Second Order which reaches

from Yesod to Chesed,1 “OT MH,” “No, certainly

not!”

32. This light shines from the jewel of the

Great Ensnarer, (Măra). The senses it bewitches, blinds the mind, and leaves

the unwary an abandoned wreck.

I

am inclined to believe that most of Blavatsky’s notes are intended as blinds.

“Light” such as is described has a technical meaning. It would be too petty to

regard Mara as a Christian would regard a man who offered him a cigarette. The

supreme and blinding light of this jewel is the great vision of Light. It is

the light which streams from the threshold of

nirvăna, and Măra is the “dweller on

the threshold.” It is absurd to call this light “evil” in any commonplace

sense. It is the two-edged sword, flaming every way, that keeps the gate of

the Tree of Life. And there is a further Arcanum connected with this which it

would be improper here to divulge.

33. The moth attracted to the dazzling

flame of thy nightlamp is doomed to perish in the viscid oil. The unwary

Soul that fails to grapple with the mocking demon of illusion, will return to

earth the slave of Mára.

The

result of failing to reject rewards is the return to earth. The temptation is

to regard oneself as having attained, and so do no more

work.

34. Behold the Hosts of Souls. Watch how

they hover o’er the stormy sea of human life, and how exhausted, bleeding,

broken-winged, they drop one after other on the swelling waves. Tossed by the

fierce winds, chased by the gale, they drift into the eddies and disappear

within the first great vortex.

In

this metaphor is contained a warning against identifying the Soul with human

life, from the failure of its aspirations.

35.

If

through the Hall of Wisdom, thou would’st reach the Vale of Bliss, Disciple,

close fast thy senses against the great dire heresy of separateness that weans

thee from the rest.

This

verse reads at first as if the heresy were still possible in the Hall of

Wisdom, but this is not as it seems. The Disciple is urged to find out his Ego

and slay it even in the beginning.

36. Let not thy “Heaven-born,” merged in

the sea of mäyă, break from the

Universal Parent (SOUL), but let the

fiery

power retire into the inmost chamber, the chamber of the Heart, and the abode

of the World’s Mother.

This

develops verse 35. The heaven-born

is the human consciousness. The chamber of the Heart is the anahata lotus. The abode of the

World’s Mother is the mulădhăra

lotus. But there is a more technical meaning yet—and this whole verse

describes a particular method of meditation, a final method, which is far too

difficult for the beginner.1

37. Then from the heart that Power shall

rise into the sixth, the middle region, the place between thin eyes, when it

becomes the breath of the ONE-SOUL, the voice which filleth all, thy Master’s

voice.

This

verse teaches the concentration of the kundalini in the ajńăcakra. “Breath” is that which

goes to and fro, and refers to the uniting of Šiva with Šakti in the sahasrara.2

38. ‘Tis only then thou canst become a

“Walker of the Sky” who treads the winds above the waves, whose

step

touches

not the waters.

This

partly refers to certain iddhi,

concerning Understanding of devas

(gods), etc.; here the word “wind” may be interpreted as “spirit.” It is

comparatively easy to reach this state, and it has no great importance. The

“walker of the sky” is much superior to the mere reader of the minds of

ants.

39. Before thou set’st thy foot upon the

ladder’s upper rung, the ladder of the mystic sounds, thou hast to hear the

voice of thy inner GOD in seven

manners.

The

word “seven” is here, as so frequently, rather poetic than mathematic; for

there are many more. The verse also reads as if it were necessary to hear all

the seven, and this is not the case— some will get one and some another. Some

students may even miss ah of them.1

40. The first is like the nightingale’s

sweet voice chanting a song of parting to its mate.

The

second comes as the sound of a silver cymbal of the dhyănis, awakening the twinkling

stars.

The

next is as the plaint melodious of the ocean-sprite imprisoned in its

shell.

And

this is followed by the chant of vina

The

fifth like sound of bamboo-flute shrills in thine ear. It changes next into a

trumpet-blast.

The

last vibrates like the dull rumbling of a

thundercloud.

The

seventh swallows alt the other sounds. They die, and then are heard no

more.

The

first four are comparatively easy to obtain, and many people can hear them at

will. The last three are much rarer, not necessarily because they are

more difficult to get, and indicate greater advance, but because the

protective envelope of the Adept is become so strong that they cannot pierce

it. The last of the seven sometimes occurs, not as a sound, but as an

earthquake, if the expression may be permitted. It is a mingling of terror and

rapture impossible to describe, and as a general rule it completely discharges

the energy of the Adept, leaving him weaker than an attack of Malaria would

do; but if the practice has been right, this soon passes off, and the

experience has this advantage, that one is far

less troubled with minor

phenomena than before. It is just possible that this is referred to in the

Apocalypse XVI, XVII, XVIII.

41. When the six are slain and at the

Master’s feet are laid, then is the pupil merged into the ONE, becomes that o

N E and lives therein.

The

note tells that this refers to the six principles, so that the subject is

completely changed. By the slaying of the principles is meant the withdrawal

of the consciousness from them, their rejection by the seeker of truth.

Sabhapaty Swămi has an excellent method on these unes;1 it is

given, in an improved form, in “Liber HHH.”2

42. Before that path is entered, thou must

destroy thy lunar body, cleanse thy mind-body and make clean thy

heart.

The

Lunar body is Nephesch, and the Mind body Ruach. The heart is Tiphareth, the

centre of Ruach.

43. Eternal life’s pure waters, clear and

crystal, with the monsoon tempest’s muddy torrents cannot

mingle.

We

are now again on the subject of suppressing thought. The pure water is the

stilled mind, the torrent the mind invaded by thoughts.

44. Heaven’s dew-drop glittering in the

morn’s first sunbeam within the bosom of the lotus, when dropped on earth

becomes a piece of clay; behold, the pearl is now a speck of

mire.

This

is not a mere poetic image. This dew-drop in the lotus is connected with the

mantra “aum mani padme hum,”3 and

to what this verse really refers is known only to members of the ninth degree

of O.T.O.

45.

Strive

with thy thoughts unclean before they overpower thee. Use them as they will

thee, for if thou sparest them and they take root and grow, know well, these

thoughts will overpower and kill thee. Beware, Disciple,

suffer

not,

e’en though it be their shadow, to approach. For it will grow, increase in

size and power, and then this

thing

of darkness will absorb thy being before thou hast well realized the black

four monster’s presence.

The

text returns to the question of suppressing thoughts. Verse 44 has been

inserted where it is in the hope of deluding the reader into the belief that

it belongs to verses 43 and 45, for

the Arcanum which it contains is so dangerous that it must be guarded in alt

possible ways. Perhaps even to call attention to it is a blind intended to

prevent the reader from looking for something else.

46. Before the “mystic Power” can make of

thee a god, Lanoo, thou must have gained the faculty to slay thy lunar form at

will.

It

is now evident that by destroying or slaying is not meant a permanent

destruction. If you can slay a thing at will it means that you can revive it

at will, for the word “faculty” implies repeated action.

47. The Self of Matter and the Self of

Spirit can never

meet. One of the twain must disappear;

there is no place for both.

This

is a very difficult verse, because

it appears so easy. It is not merely a question of Advaitism, it

refers to the spiritual marriage.1

48. Ere thy Soul’s mind can understand, the

bud of personality must be crushed out, the worm of sense destroyed past

resurrection.

This

is again filled with deeper meaning than that which appears on the surface.

The words “bud” and “worm” form a clue.

49. Thou canst not travel on the Path

before thou hast become that Path itself.

Compare

the scene in Parsifal, where the

scenery comes to the knight instead of the knight going to the scenery. But

there is also implied the doctrine of the tao, and only one who is an

accomplished Taoist can hope to understand this

verse.1

50.

Let

thy Soul lend its ear to every cry of pain like as the lotus bares its heart

to drink the morning sun.

51. Let not the fierce sun dry one tear of

pain before thyself hast wiped it from the sufferer’s

eye.

52.

But

let each burning human tear drop on thy heart and there remain; nor ever brush

it off, until the pain that caused it is removed.

This

is a counsel never to forget the original stimulus which has driven you to the

Path, the “first noble truth.” Everything is now “good.” This is why verse 53 says that these tears are the

streams that irrigate the fields of charity immortal. (Tears, by the way.

Think!)

53. These tears, O thou of heart most

merciful, these are

the

streams that irrigate the fields of charity immortal. ‘Tis on such soil that

grows the midnight blossom of Buddha, more difficult to find, more rare to

view than is the flowers of the vogay

tree. It is the seed of freedom from rebirth. It isolates the arhat both from strife and lust, it

leads him through the fields of Being unto the peace and bliss known only in

the land of Silence and Non-Being.

The

“midnight blossom” is a phrase connected with the doctrine of the Night of

Pan, familiar to Masters of the Temple. “The Poppy that flowers in the dusk”2

is another name for it. A most secret Formula of Magick is connected with this

“Heart of the Circle.”

54.

Kill

out desire; but if thou killest it take heed lest from the dead it should

again rise.

By

“desire” in al! mystic treatises of any merit is meant tendency. Desire is

manifested universally in the law of gravitation, in that of chemical

attraction, and so on; in fact, everything that is done is caused by the

desire to do it, in this technical sense of the word. The “midnight blossom”

implies a certain monastic Renunciation of al! desire, which reaches to all

planes. One must however distinguish between desire, which means unnatural

attraction to an ideal, and love, which is natural

Motion.

55.

Kill

love of life, but if thou slayest tanhă,1 let this not be for

thirst of life eternal, but to replace the fleeting by the

everlasting.

This

particularizes a special form of desire. The English is very obscure to any

one unacquainted with Buddhist literature. The “everlasting” referred to is

not a life-condition at all.

56.

Desire

nothing. Chafe not at karma, nor at

Nature’s

changeless

laws. But struggle only with the personal, the transitory, the evanescent and

the perishable.

The

words “desire nothing” should be interpreted positively as well as negatively.

The main sense of the rest of the verse is to advise the Disciple to work, and

not to complain.

57.

Help

Nature and work on with her; and Nature will

regard

thee as one of her creators and make obeisance.

Although

the object of the Disciple is to transcend Law, he must work through Law to

attain this end.

It

may be remarked that this treatise—and this comment for the most part—is

written for disciples of certain grades only. It is altogether inferior to

such Books as Liber CXI Aleph; but

for that very reason, more useful, perhaps, to the average seeker.

58. And she will open wide before thee the

portals of her secret chambers, lay bare before thy gaze the treasures hidden

in the depths of her pure virgin bosom. Unsullied by the hand of matter

she shows her treasures only to the eye of Spirit—the eye which never closes,

the eye for which there is no veil in all her kingdoms.

This

verse reminds one of the writings of Alchemists; and it should be interpreted

as the best of them would have interpreted

it.

59.

Then

will she show thee the means and way, the first gate and the second, the

third, up to the very seventh. And then, the goal—beyond which he, bathed in

the sunlight of the Spirit, glories untold, unseen by any save the eye of

Soul.

These

gates are described in the third treatise. The words “spirit” and “soul” are

highly ambiguous, and had better be regarded as poetic figures, without a

technical meaning being sought.

60. There is but one road to the Path; at

its very end alone the “Voice of the Silence” can be heard. The ladder by

which the candidate ascends is formed of rungs of suffering and pain; these

can be silenced only by the voice of virtue. Woe, then, to thee, Disciple, if

there is one single vice thou hast not left behind. For then the ladder will

give way and overthrow thee; its foot rests in the deep mire of thy sins and

failings, and ere thou canst attempt to cross this wide abyss of matter thou

hast to lave thy feet in Waters of Renunciation.

Beware lest thou should’st

set a foot still soiled upon the ladder’s lowest rung. Woe unto him who dares

pollute one rung with miry feet. The foul and viscous mud will dry, become

tenacious, then glue his feet unto the spot, and like a bird caught in the

wily fowler’s lime, he will be stayed from further progress. His vices will

take shape and drag him down. His sins will raise their voices like as the

jackal’s laugh and sob after the sun goes down; his thoughts become an army,

and bear him off a captive slave.

A

warning against any impurity in the original aspiration of the Disciple. By

impurity is meant, and should always be meant, the mingling (as opposed to the

combination) of two things. Do one thing at a time. This is particularly

necessary in the matter of the aspiration. For if the aspiration be in any way

impure, it means divergence in the will itself; and this is will’s one fatal

flaw. It will however be understood that aspiration constantly changes and

develops with progress.

The beginner can only see a certain distance. Just so

with our first telescopes we discovered many new stars, and with each

improvement in the instrument we have discovered more. The second and more

obvious meaning in the verse preaches the practice of yama, niyama, before serious

practice is started, and this in actual

life means, map out your career

as well as you can. Decide to do so many hours’ work a day in such conditions

as may be possible. It does not mean that you should set up neuroses and

hysteria by suppressing your natural instincts, which are perfectly right on

their own plane, and only wrong when they invade other planes, and set up

alien tyrannies.

61.

Kill thy desires,

Lanoo, make thy vices impotent, ere the first step is taken on the solemn

journey.

By

“desires” and “vices” are meant those things which you yourself think to

be inimical to the work; for each man they will be quite different, and any

attempt to lay down a general rule leads to worse than

confusion.

62. Strangle thy sins, and make them dumb

for ever, before thou dost lift one foot to mount the

ladder.

This

is merely a repetition of verse 61 in different language. But remember: “The

word of Sin is Restriction.” “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the

Law.”1

63. Silence thy thoughts and fix thy whole

attention on thy

Master

whom yet thou dost not see, but whom thou feelest.

This

again commands the stilling of thoughts. The previous verses referred rather

to emotions, which are the great stagnant pools on which the mosquito thought

breeds. Emotions are objectionable, as they represent an invasion of the

mental plane by sensory or moral impressions.

64. Merge into one sense thy senses, if

thou would’st be secure against the foe. ‘Tis by that sense alone which lies

concealed within the hollow of thy brain, that the steep path which leadeth to

thy Master may be disclosed before thy Soul’s dim eyes.

This

verse refers to a Meditation practice somewhat similar to those described in

“Liber 831.

65. Long and weary is the way before thee,

O Disciple. One single thought about the past that thou hast left behind, will

drag thee down and thou wilt have to start the climb

anew.

Remember

Lot’s wife.

66. Kill in thyself al! memory of past

experiences. Look not behind or thou art lost.

Remember

Lot’s wife.

It is a division of Will to

dwell in the past. But one’s past experiences must be built into one’s

Pyramid, as one advances, layer by layer. One must also remark that this verse

only applies to those who have not yet

come co reconcile past, present, and

future.

Every incarnation is a Veil of Isis.

67.

Do not believe that lust

can ever be killed out if gratified or satiated, for this is an

abomination inspired by Măra. It is by feeding více that it expands and waxes

strong, like to the worm that fattens on the blossom’s

heart.

This verse must not be

taken in its literal sense. Hunger is not conquered by starvation. One’s

attitude to all the necessities which the traditions of earthly life involve

should be to rule them, neither by mortification nor by indulgence. In order

co do the work you must keep in proper physical and mental condition. Be

sane. Asceticism always excites the mind, and the object of the Disciple is to

calm it. However, ascetic originally meant

athletic,

and it has only acquired its modern meaning on account of the corruptions that

crept into the practices used by those in “training.”

The prohibitions,

relatively valuable, were exalted into general rules. To “break training” is

not a sin for anyone who is not in training. Incidentally, it takes all sorts

to make a world. Imagine the stupidity of a universe full of arhats! All work and no play makes

Jack a dull boy.

68. The rose must re-become the bud born of

its parent

stem,

before the parasite has eaten through its heart and drunk its

life-sap.

The

English is here ambiguous and obscure, but the meaning is that it is important

to achieve the Great Work while you have youth and

energy.

69. The golden tree puts forth its

jewel-buds before its trunk is withered by the storm.

Repeats

this in clearer language.

70. The Pupil must regain the child-state he has lost ere the

first sound can fall upon his ear.

Compare

the remark of “Christ,” “Except ye become as little children ye shall in no

wise enter into the Kingdom of Heaven,” and also, “Ye must be born again.”1 It

also refers to the overcoming of shame and of the sense of sin. If you

think the Temple of the Holy Ghost to be a pig-style, it is certainly improper

to perform therein the Mass of the Graal. Therefore purify and consecrate

yourselves; and then, Kings and Priests unto God, perform ye the Miracle of

the One Substance.

71. The light from the ONE Master, the one

unfading

golden

light of Spirit, shoots its effulgent beams on the disciple from the very

first. lts rays thread through the thick, dark clouds of

Matter.

The

Holy Guardian Angel is already aspiring to union with the Disciple, even

before his aspiration is formulated in the latter.

72. Now here, now there, these rays

illumine it, like sunsparks light the earth through the thick foliage of

jungle growth. But, O Disciple, unless the flesh is passive, head cool, the

soul as firm and pure as flaming diamond, the radiance will not reach the

chamber,

its

sunlight will not warm the heart, nor will the mystic sounds of ăkăsic heights reach the ear, however

eager, at the initial stage.

The

uniting of the Disciple with his Angel depends upon the former. The Latter is

always at hand. “Akašic

heights”—the dwelling-place of Nuit.

73. Unless thou hearest, thou canst not

see.

Unless

thou seest, thou canst not hear. To hear and see this is the second

stage.

This

is an obscure verse. It implies that the qualities of fire and Spirit

commingle to reach the second stage. There is evidently a verse missing, or

rather omitted, as may be understood by the row of dots; this presumably

refers to the third stage. This third stage may be found by the discerning in

“Liber 831.”

74. When the disciple sees and hears, and

when he smells and tastes, eyes closed, ears shut, with mouth and nostrils

stopped; when the four senses blend and ready are to pass into the fifth, that

of the inner touch—then into stage the fourth he hath passed

on.

The

practice indicated in verse 74 is described in most books upon the tatwas. The orifices of the face being

covered with the fingers, the senses take on a new

shape.

75.

And

in the fifth, O slayer of thy thoughts, all these again have to be killed

beyond reanimation.

It

is not sufficient to get rid temporarily of one’s obstacles. One must seek out

their roots and destroy them, so that they can never rise again. This involves

a very deep psychological investigation, as a preliminary. But the whole

matter is one between the Self and its modifications, not at all between the

Instrument and its gates. To kill out the sense of sight is nor achieved by

removing the eyes. This mistake has done more to obscure the Path than any

other, and has been responsible for endless misery.

76. Withhold thy mind from ah external

objects, ah

external

sights. Withhold internal images, hest on thy Soul-light a dark shadow they

should cast.

This

is the usual instruction once more, but, going further, it intimates that

the internal image or reality of the object must be destroyed as well as the

outer image and the idea! image.

77. Thou art now in

dhărană,

the

sixth stage.

Dharana

has

been explained thoroughly in Book 4, q.v.1

78. When thou hast passed into the seventh,

O happy one, thou shall perceive no more the sacred three, for thou shalt have

become that three thyself. Thyself and mind, like twins upon a line, the star

which is thy goal, burns overhead. The three that dwell in glory and in bliss

ineffable, now in the world of măyă have host their names. They have

become one star, the fire that burns but scorches not, that fire which is the

upădhi2 of the

Flame.

It would be a mistake to attach more than a poetic meaning to

these remarks upon the sacred Three; but Ego, non-Ego, and That which is

formed from their wedding, are here referred to. There are two Triangles of

especial importance to mystics; one is the equilateral, the other that

familiar to the Past Master in Craft Masonry. The last sentence in the text

refers to the “Seed” of Fire, the “Ace of Wands,” the “Lion-Serpent,” the

“Dwarf-Self,” the “Winged Egg,” etc., etc., etc.

79. And this, O yogin of success, is what men cali dhyăna, the right precursor of samădhi.

These

states have been sufficiently, and much better, described in Book 4, q.v.3

80. And now thy Self is lost in SELF, thyself unto THYSELF, merged in THAT

SELF from which thou first didst

radiate.

In

this verse is given a hint of the underlying philosophical theory of the

Cosmos. See Liber CXI for a full

and proper account of this.

81. Where is thy individuality, Lanoo,

where the Lanoo

himself?

It is the spark lost in the fire, the drop within the ocean, the ever-present

Ray become the ALL and the eternal radiance.

Again

principally poetical. The man is conceived as a mere accretion about his

“Dwarf-Self,” and he is now wholly absorbed therein. For IT is also ALL, being

of the Body of Nuit.

82. And now, Lanoo, thou art the doer and

the witness, the radiator and the radiation, Light in the Sound, and

the

Sound

in the Light.

Important,

as indicating the attainment of a mystical state, in which you are not only

involved in an action, but apart from it. There is a higher state described in

the Bhagavad-gtta. “I who am al!,

and made it al!, abide its separate Lord.”1

83. Thou art acquainted with the five

impediments, O

blessed

one. Thou art their conqueror, the Master of the sixth, deliverer of the four

modes of Truth. The Light that falls upon them shines from thyself, O thou who

wast Disciple but art Teacher now.

The

five impediments are usually taken to be the five senses. In this case the

term “Master of the sixth” becomes of profound significance. The “sixth sense”

is the race-instinct, whose common manifestation is in sex; this sense is then

the birth of the Individual or Conscious Self with the “Dwarf-Self,” the

Silent Babe, Harpocrates. The “four modes of Truth” (noble Truths) are

adequately described in “Science and Buddhism.”

84. And

of these modes of

Truth:—Hast

thou not passed through knowledge of all misery—Truth the

first?

85.

Hast

thou not conquered the Măras’ King at Tsi, the portal of assembling—truth the

second?

86. Hast thou not sin at the third gate

destroyed and truth the third attained?

87. Hast thou not entered Tau, “the Path”

that leads to knowledge—the fourth truth?

The

reference to the “Măras’ King” confuses the second truth with the third. The

third Truth is a mere corollary of the Second, and the Fourth a Grammar of the

Third.

88. And now, rest ‘neath the

bodhi tree, which is perfection of a!!

knowledge, for, know, thou art the Master of

samădhi—the state of faultless

vision.

This

account of samadhi is very

incongruous. Throughout the whole treatise Hindu ideas are painfully mixed

with Buddhist, and the introduction of the “four noble truths” comes very

strangely as the precursor of verses 88 and 89.

89. Behold! thou hast become the light,

thou hast become the Sound, thou art thy Master and thy God. Thou art THYSELF

the object of thy search: the VOICE unbroken, that resounds throughout

eternities, exempt from change, from sin exempt, the seven sounds in one,

the

VOICE

OF THE SILENCE

Auth

Tat Sat.

This

is a pure peroration, and clearly involves an egocentric

metaphysic.

The

style of the whole treatise is

characteristically

occidental

![]() “to work curiously, to

adorn, to exercise, to train. ”The Latin ars is derived from this same word.

Artist, in its finest sense of creative craftsman, is therefore the best

translation. The word has degenerated under Puntan foulness.

“to work curiously, to

adorn, to exercise, to train. ”The Latin ars is derived from this same word.

Artist, in its finest sense of creative craftsman, is therefore the best

translation. The word has degenerated under Puntan foulness.