|

Acknowledgements

Fingerprints of the Gods could not have been written without the

generous, warm-hearted and sustaining love of my partner Santha

Faiia— who always gives more than she takes and who enriches the

lives of everyone around her with creativity, kindness and

imagination. All the photographs in the book are her work.

I am also grateful for the support and encouragement of our six

children—Gabrielle, Leila, Luke, Ravi, Sean and Shanti—each one of

whom I feel privileged to know.

My parents, Donald and Muriel Hancock, have been incredibly helpful,

active and involved through this and many other difficult times and

projects. Together with my uncle James Macaulay they have also

patiently read the drafts of the evolving manuscript, offering a

wealth of positive suggestions. Thanks, too, to my oldest and

closest friend, Peter Marshall, with whom I have weathered many

storms, and to Rob Gardner, Joseph and Sherry Jahoda, Roel Oostra,

Joseph and Laura Schor, Niven Sinclair, Colin Skinner and Clem

Vallance, all of whom gave me good advice.

In 1992 I suddenly found that I had a friend in Lansing, Michigan.

His name is Ed Ponist and he got in touch with me soon after the

publication of my previous book, The Sign and the Seal. Like a

guardian angel he volunteered to devote a hefty chunk of his spare

time to helping me out in the US with research, contacts and the

collection of documentary resources of relevance to Fingerprints of

the Gods.

He did a brilliant job, always sending me the right books

just when I needed them and finding references that I didn’t even

know existed. He was also an accurate weather-vane on the quality of

my work, whose judgment I quickly learned to trust and respect.

Last but not least, when Santha and I went to Arizona, to the Hopi

Nation, it was Ed who came with us and who opened the way.

Ed’s initial letter was part of an overwhelming deluge of mail that

I received from around the world after writing The Sign and the

Seal. For a while I tried to answer all the letters individually.

Eventually, however, I got swamped with the new work on Fingerprints

and had to stop replying. I feel bad about this, and would like to

take this opportunity to thank everybody who wrote to me and to whom

I did not write back. I’m intending to be more systematic in the

future because I enormously value this correspondence and appreciate

the high-quality information that it frequently turns out to contain

...

Other researchers who have helped me on Fingerprints of the Gods

have been Martin Slavin, David Mestecky and Jonathan Derrick. In

addition I would like to thank my Anglophone editors on both sides

of the Atlantic, Tom Weldon at Heinemann, Jim Wade at Crown and John

Pearce at Doubleday Canada, as well as my literary agents Bill

Hamilton and Sara Fisher, for their continuing commitment,

solidarity and wise counsel.

My warmest appreciation also to those co-researchers and colleagues

who have become my friends during the course of this investigation:

Robert Bauval in Britain (with whom I shall be co-authoring two

future books on related subjects), Colin Wilson, John Anthony West

and Lew Jenkins in the United States, Rand and Rose Flem-Ath and

Paul William Roberts in Canada.

Finally I want to pay tribute to Ignatius Donnelly, Arthur Posnansky,

R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz, Charles Hapgood and Giorgio de Santillana—

investigators who saw that something was badly wrong with the

history of mankind, who had the courage to speak out against

intellectual adversity, and who pioneered the momentous paradigm

shift that is now irrevocably under way.

Back to

Contents

Part I

The Mystery of the Maps

Chapter 1 -

A Map of Hidden Places

8 RECONNAISSANCE TECHNICAL SQUADRON (SAC)

UNITED STATES AIRFORCE

Westover Airforce Base

Massachusetts

6 July 1960

SUBJECT: Admiral Piri Reis World Map

To: Professor Charles H. Hapgood,Keene College,Keene, New Hampshire.

Dear Professor Hapgood,

Your request for evaluation of certain unusual features of the

Piri

Reis World Map of 1513 by this organization has been reviewed.

The claim that the lower part of the map portrays the Princess

Martha Coast of Queen Maud Land Antarctica, and the Palmer

Peninsula, is reasonable. We find this is the most logical and in

all probability the correct interpretation of the map.

The geographical detail shown in the lower part of the map agrees

very remarkably with the results of the seismic profile made across

the top of the ice-cap by the Swedish-British Antarctic Expedition

of 1949.

This indicates the coastline had been mapped before it was covered

by the ice-cap.

The ice-cap in this region is now about a mile thick.

We have no idea how the data on this map can be reconciled with the

supposed state of geographical knowledge in 1513.

HAROLD Z. OHLMEYER

Lt Colonel, USAF Commander

Despite the deadpan language, Ohlmeyer’s letter1 is a bombshell. If

Queen Maud Land was mapped before it was covered by ice, the

original cartography must have been done an extraordinarily long

time ago.

1

Letter reproduced in Charles H. Hapgood FRGS,

Maps of the Ancient

Sea Kings, Chilton Books, Philadelphia and New York, 1966, p. 243.

How long ago exactly?

Conventional wisdom has it that the Antarctic ice-cap, in its

present extent and form, is millions of years old. On closer

examination, this notion turns out to be seriously flawed—so

seriously that we need not assume the map drawn by Admiral Piri Reis

depicts Queen Maud Land as it looked millions of years in the past.

The best recent evidence

suggests that Queen Maud Land, and the neighbouring regions shown on

the map, passed through a long ice-free period which may not have

come completely to an end until about six thousand years ago.2 This

evidence, which we shall touch upon again in the next chapter,

liberates us from the burdensome task of explaining who (or what)

had the technology to undertake an accurate geographical survey of

Antarctica in, say, two million BC, long before our own species came

into existence.

By the same token, since map-making is a complex and

civilized activity, it compels us to explain how such a task could

have been accomplished even six thousand years ago, well before the

development of the first true civilizations recognized by

historians.

Ancient sources

In attempting that explanation it is worth reminding ourselves of

the basic historical and geological facts:

1 - The Piri Reis Map, which is a genuine document, not a hoax of any

kind, was made at Constantinople in AD 1513.3

2 - It focuses on the

western coast of Africa, the eastern coast of South America and the

northern coast of Antarctica.

3 - Piri Reis could not have acquired his information on this latter

region from contemporary explorers because Antarctica remained

undiscovered until AD 1818,4 more than 300 years after he drew the

map.

4 - The ice-free coast of Queen Maud Land shown in the map is a

colossal puzzle because the geological evidence confirms that the

latest date it could have been surveyed and charted in an ice-free

condition is 4000 BC.5

5 - It is not possible to pinpoint the earliest date that such a task

could have been accomplished, but it seems that the Queen Maud Land

littoral may have remained in a stable, unglaciated condition for at

least 9000 years before the spreading ice-cap swallowed it

entirely.6

6 - There is no civilization known to history that had the capacity or

need

to survey that coastline in the relevant period: between 13,000 BC

and

4000 BC.7

2 Ibid., pp. 93-98, 235. The period lasted from about 13000 BC to

4000 BC according, for example, to the findings of Dr Jack Hough of

Illinois University, supported by experts at the Carnegie

Institution, Washington DC. John G. Weiphaupt, a University of

Colorado specialist in seismology and gravity and planetary geology,

is another who supports the view of a relatively late ice-free

period in at least parts of Antarctica. Together with a number of

other geologists, he places that period in a narrower band than

Hough et al.—from 7000 BC to 4000 BC.

3 Ibid., preface, pp. 1,

209-211.

4 Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1991, I:440.

5 Maps of The

Ancient Sea Kings, p. 235.

6 Ibid.

7 Historians recognize no ‘civilizations’ as such prior to 4000 BC.

In other words, the true enigma of this 1513 map is not so much its

inclusion of a continent not discovered until 1818 but its portrayal

of part of the coastline of that continent under ice-free conditions

which came to an end 6000 years ago and have not since recurred.

How can this be explained? Piri Reis obligingly gives us the answer

in a series of notes written in his own hand on the map itself. He

tells us that he was not responsible for the original surveying and

cartography. On the contrary, he admits that his role was merely

that of compiler and copyist and that the map was derived from a

large number of source maps.8 Some of these had been drawn by

contemporary or near-contemporary explorers (including

Christopher

Columbus), who had by then reached South America and the Caribbean,

but others were documents dating back to the fourth century BC or

earlier.9

Piri Reis did not venture any suggestion as to the identity of the

cartographers who had produced the earlier maps. In 1963, however,

Professor Hapgood proposed a novel and thought-provoking solution to

the problem. He argued that some of the source maps the admiral had

made use of, in particular those said to date back to the fourth

century BC, had themselves been based on even older sources, which

in turn had been based on sources originating in the furthest

antiquity. There was, he asserted, irrefutable evidence that the

earth had been comprehensively mapped before 4000 BC by a hitherto

unknown and undiscovered civilization which had achieved a high

level of technological advancement.10

It appears [he concluded] that accurate information has been passed

down from people to people. It appears that the charts must have

originated with a people unknown and they were passed on, perhaps by

the Minoans and the Phoenicians, who were, for a thousand years and

more, the greatest sailors of the ancient world. We have evidence

that they were collected and studied in the great library of

Alexandria [Egypt] and that compilations of them were made by the

geographers who worked there.11

8

Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings, pp. 220-4.

9 Ibid., p. 222.

10 Ibid., p. 193

11

Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings (revised edition), Turnstone Books,

London, 1979, preface.

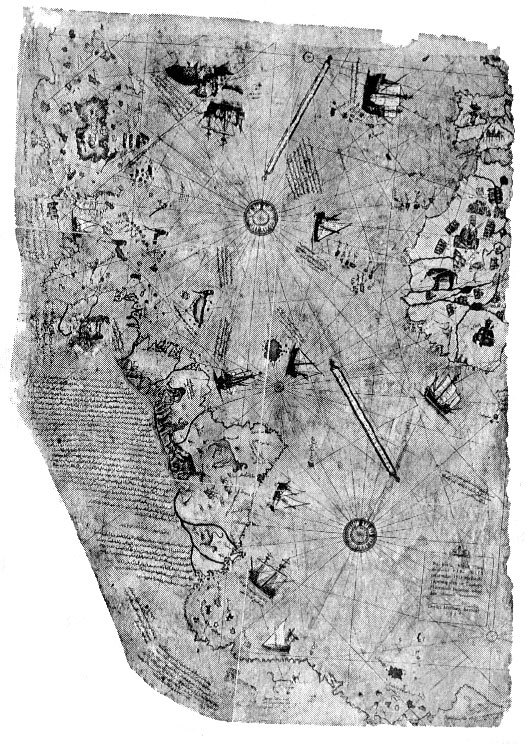

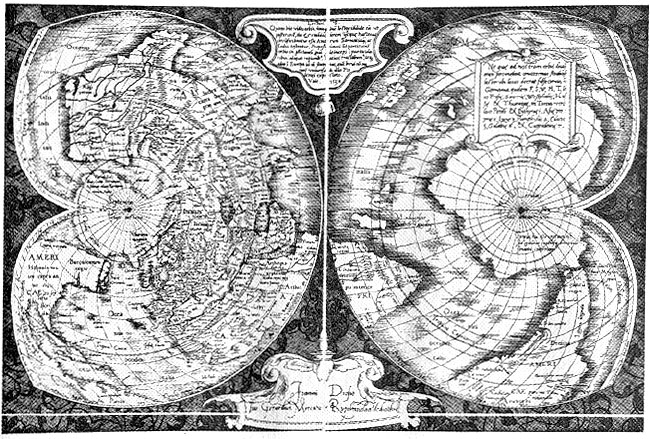

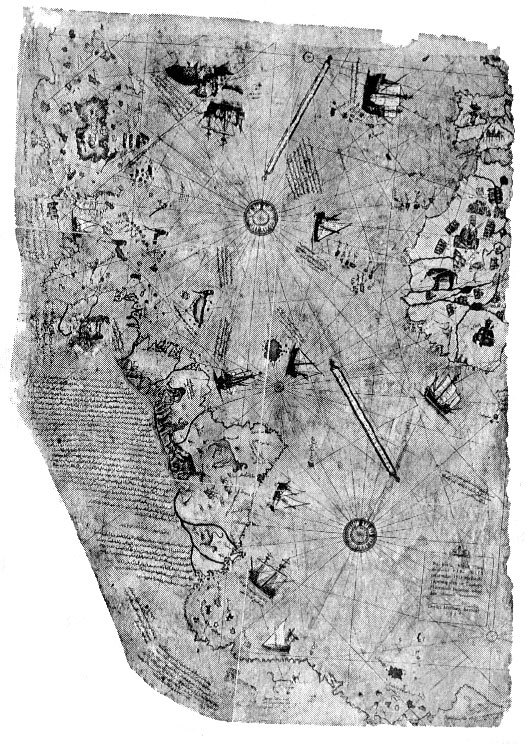

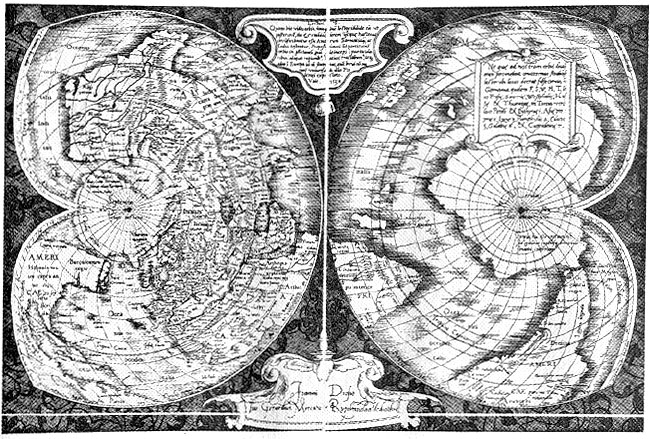

Piri Reis map (original)

Redrawing to show detail

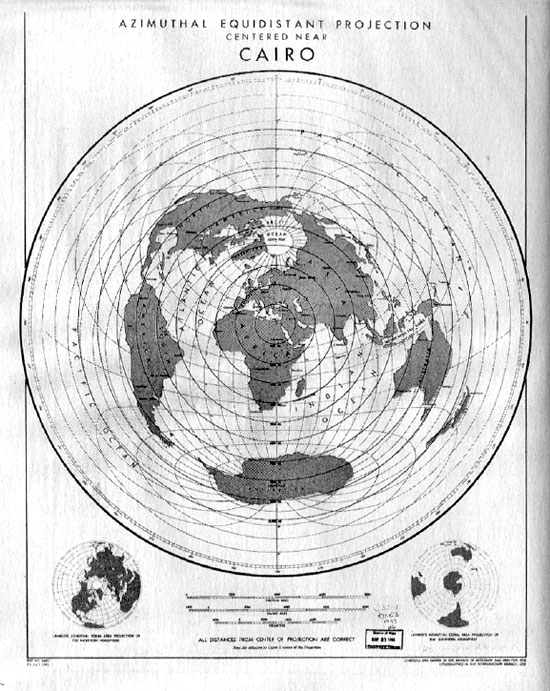

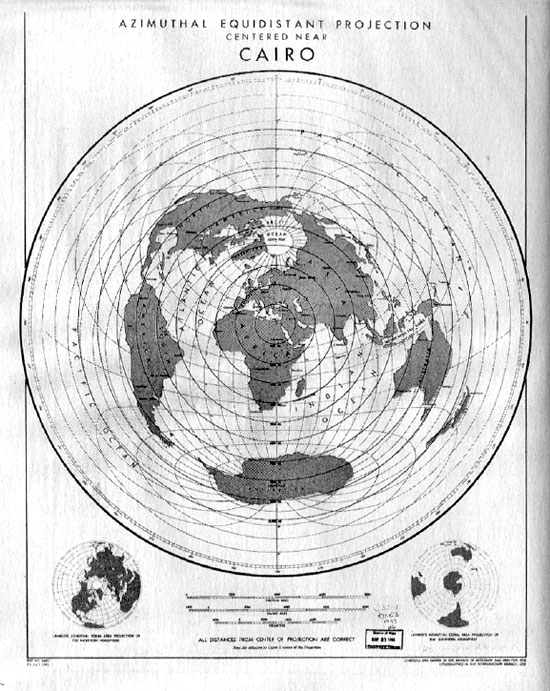

The US Airforce map shows the probable projection that governed the

layout of the ancient Piri Reis map.

From Alexandria, according to Hapgood’s reconstruction, copies of

these compilations and of some of the original source maps were

transferred to other centers of learning—notably Constantinople.

Finally, when Constantinople was seized by the Venetians during the

Fourth Crusade in 1204, the maps began to find their way into the

hands of European sailors and adventurers:

Most of these maps were of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. But

maps of other areas survived. These included maps of the Americas

and maps of the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans. It becomes clear that

the ancient voyagers travelled from pole to pole. Unbelievable as it

may appear, the evidence nevertheless indicates that some ancient

people explored Antarctica when its coasts were free of ice. It is

clear, too, that they had an instrument of navigation for accurately

determining longitudes that was far superior to anything possessed

by the peoples of ancient, medieval or modern times until the second

half of the eighteenth century.

This evidence of a lost technology will support and give credence to

many of the other hypotheses that have been brought forward of a

lost civilization in remote times. Scholars have been able to

dismiss most of that evidence as mere myth, but here we have

evidence that cannot be dismissed. The evidence requires that all

the other evidence that has been brought forward in the past should

be re-examined

with an open mind.12

Despite a ringing endorsement from Albert Einstein (see below), and

despite the later admission of John Wright, president of the

American Geographical Society, that Hapgood had ‘posed hypotheses

that cry aloud for further testing’, no further scientific research

has ever been undertaken into these anomalous early maps.

Moreover,

far from being applauded for making a serious new contribution to

the debate about the antiquity of human civilization, Hapgood until

his death was cold-shouldered by the majority of his professional

peers, who couched their discussion of his work in what has

accurately been described as ‘thick and unwarranted sarcasm,

selecting trivia and factors not subject to verification as the

bases for condemnation, seeking in this way to avoid the basic

issues’.13

A man ahead of his time

The late Charles Hapgood taught the history of science at Keene

College, New Hampshire, USA. He wasn’t a geologist, or an ancient

historian. It is possible, however, that future generations will

remember him as the man whose work undermined the foundations of

world history—and a large chunk of world geology as well.

Albert Einstein was among the first to realize this when he took the

unprecedented step of contributing the foreword to a book Hapgood

wrote in 1953, some years before he began his investigation of

the Piri Reis Map:

I frequently receive communications from people who wish to consult

me concerning their unpublished ideas [Einstein observed]. It goes

without saying that these ideas are very seldom possessed of

scientific validity. The very first communication, however, that I

received from Mr. Hapgood electrified me. His idea is original, of

great simplicity, and—if it continues to prove itself—of great

importance to everything that is related to the history of the

earth’s surface.14

12

- Ibid.

13 -

Ibid., foreword. See also F. N. Earll, foreword to C. H. Hapgood,

Path of the Pole, Chilton Books, New York, 1970, p. viii.

14 -

From Einstein's foreword (written in 1953) to Charles H. Hapgood,

Earth's Shifting Crust: A Key to Some Basic Problems of Earth

Science, Pantheon Books, New York, 1958, pp. 1-2.

The ‘idea’ expressed in Hapgood’s 1953 book is a global geological

theory which elegantly explains how and why large parts of

Antarctica could have remained ice-free until 4000 BC, together with

many other anomalies of earth science. In brief the argument is:

1 - Antarctica was not always covered with ice and was at one time

much warmer than it is today.

2 - It was warm because it was not physically located at the South

Pole in that period. Instead it was approximately 2000 miles farther

north. This ‘would have put it outside the Antarctic Circle in a

temperate or cold temperate climate’.15

3 - The continent moved to its present position inside the Antarctic

Circle as a result of a mechanism known as ‘earth-crust

displacement’. This mechanism, in no sense to be confused with

plate-tectonics or ‘continental drift’, is one whereby the

lithosphere, the whole outer crust of the earth, ‘may be displaced

at times, moving over the soft inner body, much as the skin of an

orange, if it were loose, might shift over the inner part of the

orange all in one piece’.16

4 - During the envisaged southwards movement of Antarctica brought

about by earth-crust displacement, the continent would gradually

have grown colder, an ice-cap forming and remorselessly expanding

over several thousands of years until it attained its present

dimensions.’17

Further details of the evidence supporting these radical proposals

are set out in Part VIII of this book. Orthodox geologists, however,

remain reluctant to accept Hapgood’s theory (although none has

succeeded in proving it incorrect). It raises many questions.

Of these by far the most important is: what conceivable mechanism

would be able to exert sufficient thrust on the lithosphere to

precipitate a phenomenon of such magnitude as a crustal

displacement?

We have no better guide than Einstein to summarize Hapgood’s

findings:

In a polar region there is continual deposition of ice,

which is not symmetrically distributed about the pole. The earth’s

rotation acts on these unsymmetrically deposited masses, and

produces centrifugal momentum that is transmitted to the rigid

crust of the earth. The constantly increasing centrifugal

momentum produced in this way will, when it has reached a

certain point, produce a movement of the earth’s crust over the

rest of the earth’s body ...18

15 Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings, 1966 ed., p. 189.

16 Ibid., p. 187.

17 Ibid., p. 189.

18 Einstein's foreword to Earth's Shifting Crust, p. 1

The Piri Reis Map seems to contain surprising collateral evidence in

support of the thesis of a geologically recent glaciation of parts

of Antarctica following a sudden southward displacement of the

earth’s crust. Moreover since such a map could only have been drawn

prior to 4000 BC, its implications for the history of human

civilization are staggering. Prior to 4000 BC there are supposed to

have been no civilizations at all.

At some risk of over-simplification, the academic consensus is

broadly:

-

Civilization first developed in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle

East.

-

This development began after 4000 BC, and culminated in the

emergence of the earliest true civilizations (Sumer and

Egypt)

around 3000 BC, soon followed by the Indus Valley and China.

-

About 1500 years later, civilization took off

spontaneously and

independently in the Americas.

-

Since 3000 BC in the Old World (and about 1500 BC in the New)

civilization has steadily ‘evolved’ in the direction of ever more

refined, complex and productive forms.

-

In consequence, and particularly by comparison with ourselves, all

ancient civilizations (and all their works) are to be understood as

essentially primitive (the Sumerian astronomers regarded the heavens

with unscientific awe, and even the pyramids of Egypt were built by

‘technological primitives’).

The evidence of the Piri Reis Map appears to contradict all this.

Piri Reis and his sources

In his day, Piri Reis was a well-known figure; his historical

identity is firmly established. An admiral in the navy of the

Ottoman Turks, he was involved, often on the winning side, in

numerous sea battles around the mid-sixteenth century. He was, in

addition, considered an expert on the lands of the Mediterranean,

and was the author of a famous sailing book, the Kitabi Bahriye,

which provided a comprehensive description of the coasts, harbours,

currents, shallows, landing places, bays and straits of the Aegean

and Mediterranean Seas. Despite this illustrious career he fell foul

of his masters and was beheaded in AD 1554 or 1555.19

The source maps Piri Reis used to draw up his 1513 map were in all

probability lodged originally in the Imperial Library at

Constantinople, to which the admiral is known to have enjoyed

privileged access. Those sources (which may have been transferred or

copied from even more ancient centers of learning) no longer exist,

or, at any rate, have not been found. It was, however, in the

library of the old Imperial Palace at Constantinople that the Piri

Reis Map was rediscovered, painted on a gazelle skin and rolled up

on a dusty shelf, as recently as 1929.20

19 Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings, pp. 209-11.

20 Ibid., p. 1.

Legacy of a lost civilization?

As the baffled Ohlmeyer admitted in his letter to

Hapgood in 1960,

the Piri Reis Map depicts the subglacial topography, the true

profile of Queen Maud Land Antarctica beneath the ice. This profile

remained completely

hidden from view from 4000 BC (when the advancing ice sheet covered

it) until it was revealed again as a result of the comprehensive

seismic survey of Queen Maud Land carried out during 1949 by a joint

British-Swedish scientific reconnaissance team.21

21 Ibid., pp. 76-7 and 231-2.

If Piri Reis had been the only cartographer with access to such

anomalous information, it would be wrong to place any great weight

on his map. At the most one might say, ‘Perhaps it is significant

but, then again, perhaps it is just a coincidence.’ However, the

Turkish admiral was by no means alone in the possession of seemingly

impossible and inexplicable geographical knowledge.

It would be

futile to speculate further than Hapgood has already done as to what

‘underground stream’ could have carried and preserved such knowledge

through the ages, transmitting fragments of it from culture to

culture and from epoch to epoch. Whatever the mechanism, the fact is

that a number of other cartographers seem to have been privy to the

same curious secrets.

Is it possible that all these map-makers could have partaken,

perhaps unknowingly, in the bountiful scientific legacy of a

vanished civilization?

Back to

Contents

Chapter 2 -

Rivers in the Southern Continent

In the Christmas recess of 1959-60 Charles Hapgood was looking for

Antarctica in the Reference Room of the Library of Congress,

Washington DC. For several consecutive weeks he worked there, lost

in the search, surrounded by literally hundreds of medieval maps and

charts.

I found [he reported] many fascinating things I had not expected to

find, and a number of charts showing the southern continent. Then,

one day, I turned a page and sat transfixed. As my eyes fell upon

the southern hemisphere of a world map drawn by Oronteus Finaeus in

1531, I had the instant conviction that I had found here a truly

authentic map of the real Antarctica.

The general shape of the continent was startlingly like the outline

of the continent on our modern maps. The position of the South Pole,

nearly in the center of the continent, seemed about right. The

mountain ranges that skirted the coasts suggested the numerous

ranges that have been discovered in Antarctica in recent years. It

was obvious, too, that this was no slapdash creation of somebody’s

imagination.

The mountain ranges were individualized, some

definitely coastal and some not. From most of them rivers were shown

flowing into the sea, following in every case what looked like very

natural and very convincing drainage patterns. This suggested, of

course, that the coasts may have been ice-free when the original map

was drawn. The deep interior, however, was free entirely of rivers

and mountains, suggesting that the ice might have been present

there.1

Closer investigation of the Oronteus Finaeus Map by Hapgood, and by

Dr Richard Strachan of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

confirmed the following:

1 - It had been copied and compiled from several earlier source maps

drawn up according to a number of different projections.2

2 - It did indeed show non-glacial conditions in coastal regions of

Antarctica, notably Queen Maud Land, Enderby Land, Wilkes Land,

Victoria Land (the east coast of the Ross Sea), and Marie Byrd

Land.3

3 - As in the case of the Piri Reis Map, the general profile of the

terrain, and the visible physical features, matched closely seismic

survey maps of the subglacial land surfaces of Antarctica.4

1 Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings (henceforth Maps), p. 79.

2 Ibid.,

p. 233.

3 Ibid., p. 89.

4 Ibid., p. 90. These maps were made in 1958, International

Geophysical Year, by survey teams from several different nations.

The Oronteus Finaeus Map, Hapgood concluded, appeared to document,

‘the surprising proposition that Antarctica was visited and perhaps

settled by men when it was largely if not entirely non-glacial. It

goes without saying that this implies a very great antiquity ...

[Indeed] the Oronteus Finaeus Map takes the civilization of the

original map-makers back to a time contemporary with the end of the

last Ice Age in the northern hemisphere.’5

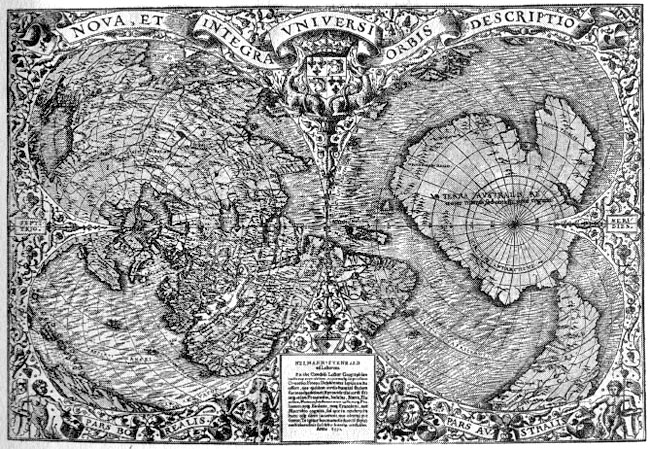

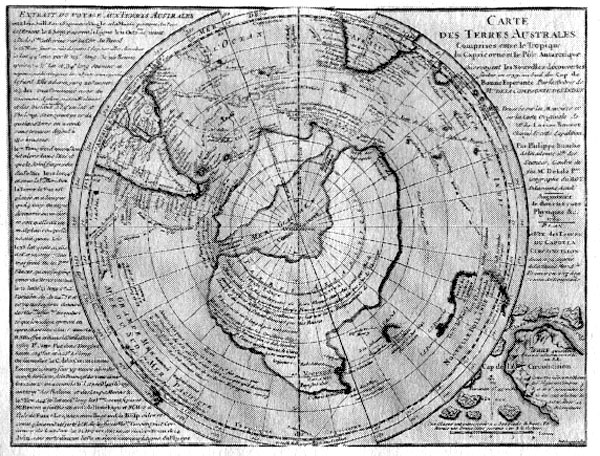

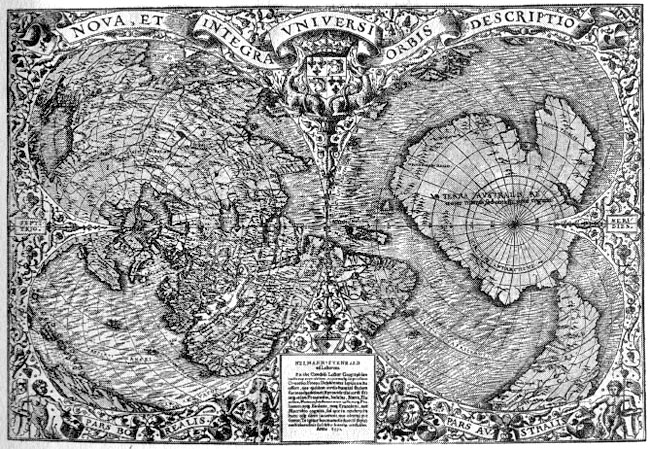

The Oronteus Finaeus map,

showing Antarctica with ice-free coasts,

mountains and rivers.

Ross Sea

Further evidence in support of this view arises from the manner in

which the Ross Sea was shown by Oronteus Finaeus. Where today great

glaciers like the Beardmore and the Scott disgorge themselves into

the sea, the 1531 map shows estuaries, broad inlets and indications

of rivers. The unmistakable implication of these features is that

there was no ice on the Ross Sea or its coasts when the source maps

used by Oronteus Finaeus were made:

‘There also had to be a

considerable hinterland free of ice to feed the rivers. At the

present time all these coasts and their hinterlands are deeply

buried in the mile-thick ice-cap, while on the Ross Sea itself there

is a floating ice-shelf hundreds of feet thick.’6

The Ross Sea evidence provides strong corroboration for the notion

that Antarctica must have been mapped by some unknown civilization

during the extensively ice-free period which ended around 4000 BC.

This is

emphasized by the coring tubes used, in 1949, by one of the

Byrd

Antarctic Expeditions to take samples of sediment from the bottom of

the Ross Sea.

The sediments showed numerous clearly demarcated

layers of stratification reflecting different environmental

conditions in different epochs:

‘coarse glacial marine’, ‘medium

glacial marine’, ‘fine glacial marine’, and so on. The most

surprising discovery, however, ‘was that a number of the layers were

formed of fine-grained, well-assorted sediments, such as are brought

down to the sea by rivers flowing from temperate (that is, ice-free)

lands ...’7

Using the ionium-dating method developed by

Dr W. D. Urry (which

makes use of three different radioactive elements found in sea

water8), researchers at the Carnegie Institute in Washington DC were

able to establish beyond any reasonable doubt that great rivers

carrying fine-grained well-assorted sediments had indeed flowed in

Antarctica until about 6000 years ago, as the Oronteus Finaeus Map

showed.

It was only after that date, around 4000 BC,

‘that the

glacial kind of sediment began to be deposited on the Ross Sea

bottom ... The cores indicate that warm conditions had prevailed for

a long period before that.’9

5 Ibid., p. 149.

6 Ibid., p. 93-6.

7 Ibid., p. 97.

8 For a detailed description of the process see Maps, P. 96.

9

Ibid., page 98.

Mercator and Buache

The Piri Reis and Oronteus Finaeus Maps therefore provide us with a

glimpse of

Antarctica as no cartographer in historical times could

possibly have seen it. On their own, of course, these two pieces of

evidence should not be sufficient to persuade us that we might be

gazing at the fingerprints of a lost civilization.

Can three, or

four, or six such maps, however, be dismissed with equal

justification?

The Mercator map,

showing Antarctica’s mountains and rivers covered

by ice.

Is it safe, or reasonable, for example, for us to continue to ignore

the historical implications of some of the maps made by the

sixteenth-century’s most famous cartographer: Gerard Kremer,

otherwise known as Mercator? Best remembered for the Mercator

projection, still used on most world maps today, this enigmatic

individual (who paid an unexplained visit to the Great Pyramid of

Egypt in 156310) was reportedly ‘indefatigable in searching out ...

the learning of long ago’, and spent many years diligently

accumulating a vast and eclectic reference library of ancient source

maps.11

10

He left his graffito there. See Peter Tompkins, Secrets of the Great

Pyramid, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, p. 38, 285.

11 Maps, p.

102.

Significantly, Mercator included the Oronteus Finaeus map in his

Atlas of 1569 and also depicted the Antarctic on several he himself

drew in the same year.

Identifiable parts of the then undiscovered

southern continent on these maps are:

-

Cape Dart and Cape Herlacher in

Marie Byrd Land

-

the Amundsen Sea

-

Thurston Island in Ellsworth

Land

-

the Fletcher Islands in the Bellinghausen Sea

-

Alexander I

Island

-

the Antarctic (Palmer) Peninsula

-

the Weddell Sea, Cape Norvegia

-

the Regula Range in Queen Maud Land (as islands)

-

the Muhlig-Hoffman Mountains (as islands)

-

the Prince Harald Coast

-

the Shirase Glacier as an estuary on Prince Harald Coast

-

Padda Island

in Lutzow-Holm Bay

-

the Prince Olaf Coast in Enderby Land

‘In

some cases these features are more distinctly recognizable than on

the Oronteus Finaeus Map,’ observed Hapgood, ‘and it seems clear, in

general, that Mercator had at his disposal source

maps other than those used by Oronteus Finaeus.’12

And not only Mercator.

Philippe Buache, the eighteenth-century French geographer, was also

able to publish a map of Antarctica long before the southern

continent was officially ‘discovered’. And the extraordinary feature

of Buache’s map is that it seems to have been based on source maps

made earlier, perhaps thousands of years earlier, than those used by

Oronteus Finaeus and Mercator.

What Buache gives us is an eerily

precise representation of Antarctica as it must have looked when

there was no ice on it at all.13 His map reveals the subglacial

topography of the entire continent, which even we did not have full

knowledge of until 1958, International Geophysical Year, when a

comprehensive seismic survey was carried out.

12 Ibid., pp. 103-4.

13 Ibid., p. 93.

That survey only confirmed what Buache had already proclaimed when

he published his map of Antarctica in 1737. Basing his cartography

on ancient sources now lost, the French academician depicted a clear

waterway across the southern continent dividing it into two

principal landmasses lying east and west of the line now marked by

the Trans-Antarctic Mountains.

Such a waterway, connecting the Ross, Weddell and Bellinghausen

Seas, would indeed exist if Antarctica were free of ice. As the 1958 IGY Survey shows, the continent (which appears on modern maps as one

continuous landmass) consists of an archipelago of large islands

with mile-thick ice packed between them and rising above sea level.

The epoch of the map-makers

As we have seen, many orthodox geologists believe that the last time

any waterway existed in these ice-filled basins was millions of

years ago. From the scholarly point of view, however, it is equally

orthodox to affirm that no human beings had evolved in those remote

times, let alone human beings capable of accurately mapping the

landmasses of the Antarctic.

The big problem raised by the Buache/IGY

evidence is that those landmasses do seem to have been mapped when

they were free of ice.

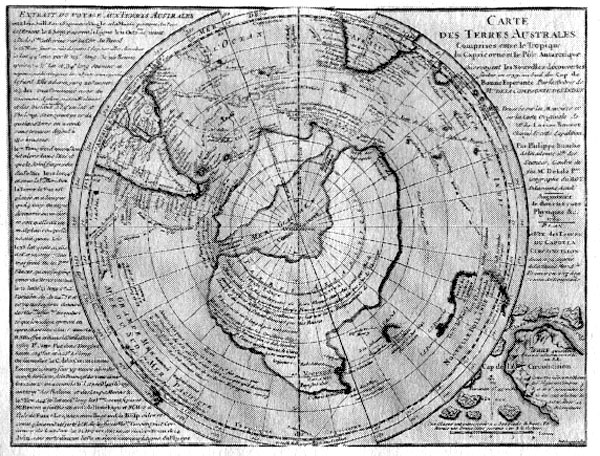

The Buache map,

with landmasses which show Antarctica very much as

it would have looked before it became covered by ice.

This confronts scholars with two

mutually contradictory propositions.

Which one is correct?

If we are to go along with orthodox geologists and accept that

millions of years have indeed elapsed since Antarctica was last

completely free of ice, then all the evidence of human evolution,

painstakingly accumulated by distinguished scientists from Darwin

on, must be wrong. It seems inconceivable that this could be the

case: the fossil record makes it abundantly clear that only the unevolved ancestors of humanity existed millions of years

ago—low-browed knuckle-dragging hominids incapable of advanced

intellectual tasks like map-making.

Are we therefore to assume the intervention of alien cartographers

in orbiting spaceships to explain the existence of sophisticated

maps of an ice-free Antarctica? Or shall we think again about the

implications of Hapgood’s theory of earth-crust displacement which

allows the southern continent to have been in the ice-free condition

depicted by Buache as little as 15,000 years ago?14

14 For a fuller discussion of the evidence behind this theory see

Part VIII of this book and Hapgood's Earth's Shifting Crust.

Above left and right: Redrawings of the Mercator and Oronteus Finaeus

maps showing the progressive glaciation of Antarctica.

Below left:

Redrawing of the Buache map.

Below right: The subglacial topography

of Antarctica, according to modern seismic surveys.

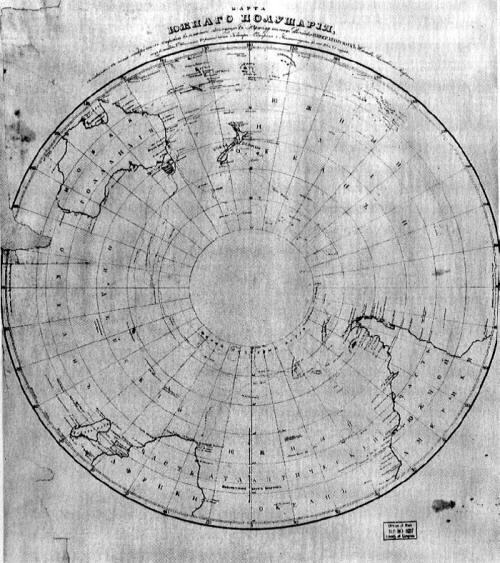

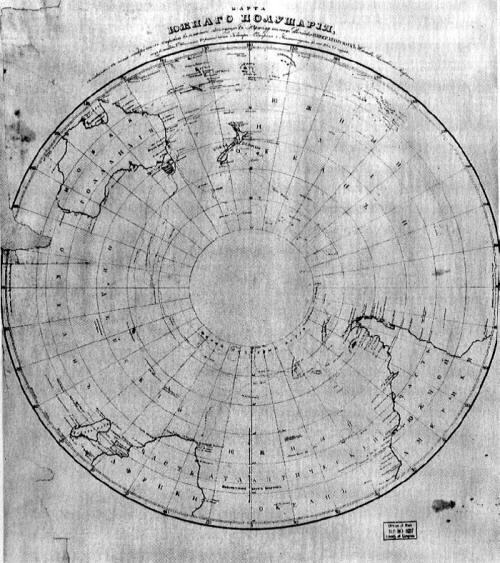

An early nineteenth-century Russian map showing that the existence

of Antarctica was at that time unknown. The continent was

‘discovered’ in AD 1818. But could it have been mapped thousands of

years earlier than that by the cartographers of an as yet

unidentified high civilization of prehistory?

Is it possible that a human civilization, sufficiently advanced to

have mapped Antarctica, could have developed by 13,000 BC and later

disappeared? And, if so, how much later?

The combined effect of the Piri Reis, Oronteus Finaeus, Mercator and

Buache Maps is the strong, though disturbing, impression that

Antarctica may have been continuously surveyed over a period of

several thousands of years as the ice-cap gradually spread outwards

from the interior, increasing its grip with every passing millennium

but not engulfing all the coasts of the southern continent until

around 4000 BC.

The original sources for the Piri Reis and

Mercator

Maps must therefore have been prepared towards the end of this

period, when only the coasts of Antarctica were free of ice; the

source for the Oronteus Finaeus Map, on the other hand, seems to

have been considerably earlier, when the icecap was present only in

the deep interior of the continent; and the source for the Buache

Map appears to originate in even earlier period (around 13,000 BC),

when there may have been no ice in Antarctica at all.

South America

Were other parts of the world surveyed and accurately charted at

widely separated intervals during this same epoch; roughly from

13,000 BC to 4000 BC? The answer may lie once again in the Piri Reis

Map, which contains more mysteries than just Antarctica:

Drawn in 1513, the map demonstrates an uncanny knowledge of South

America—and not only of its eastern coast but of the Andes mountains

on the western side of the continent, which were of course unknown

at that time. The map correctly shows the Amazon River rising in

these unexplored mountains and thence flowing eastwards.15

Itself compiled from more than twenty different source documents of

varying antiquity,16 the Piri Reis Map depicts

the Amazon not once

but twice (most probably as a result of the unintentional

overlapping of two of the source documents used by the Turkish

admiral17). In the first of these the Amazon’s course is shown down

to its Para River mouth, but the important island of Marajo does not

appear.

According to Hapgood, this suggests that the relevant source

map must have dated from a time, perhaps as much as 15,000 years

ago, when the Para River was the main or only mouth of the Amazon

and when Marajo Island was part of the mainland on the northern side

of the river.18

The second depiction of the Amazon, on the other

hand, does show Marajo (and in fantastically accurate detail)

despite the fact that this island was not discovered until 1543.19

Again, the possibility is raised of an unknown civilization which

undertook continuous surveying and mapping operations of the

changing face of the earth over a period of many thousands of years,

with Piri Reis making use of earlier and later source maps left

behind by this civilization.

15 Maps, p. 68.

16 Ibid., p. 222.

17 Ibid., pp. 64-5.

18 Ibid., p.

64.

19 Ibid., p. 65.

Neither the Orinoco River nor its present delta is represented on

the Piri Reis Map. Instead, as Hapgood proved,

‘two estuaries

extending far inland (for a distance of about 100 miles) are shown

close to the site of the present river. The longitude on the grid

would be correct for the

Orinoco, and the latitude is also quite accurate. Is it possible

that these estuaries have been filled in, and the delta extended

this much, since the source maps were made?’20

Although they remained undiscovered until 1592, the

Falkland Islands

appear on the 1513 map at their correct latitude.21

The library of ancient sources incorporated in the

Piri Reis Map may

also account for the fact that it convincingly portrays a large

island in the Atlantic Ocean to the east of the South American coast

where no such island now exists.

Is it pure coincidence that this

‘imaginary ’ island turns out to be located right over the

sub-oceanic Mid-Atlantic Ridge just north of the equator and 700

miles east of the coast of Brazil, where the tiny Rocks of Sts.

Peter and Paul now jut above the waves?22 Or was the relevant source

map drawn deep in the last Ice Age, when sea levels were far lower

than they are today and a large island could indeed have been

exposed at this spot?

20 Ibid., p. 69.

21 Ibid., p. 72.

22 Ibid., p. 65.

Sea levels and ice ages

Other sixteenth-century maps also look as though they could have

been based on accurate world surveys conducted during the last Ice

Age. One was compiled by the Turk Hadji Ahmed in 1559, a

cartographer, as Hapgood puts it, who must have had access to some

‘most extraordinary’ source maps.23

The strangest and most immediately striking feature of Hadji Ahmed’s

compilation is that it shows quite plainly a strip of territory,

almost 1000 miles wide, connecting Alaska and Siberia. Such a

‘land-bridge’, as geologists refer to it, did once exist (where the

Bering Strait is now) but was submerged beneath the waves by rising

sea levels at the end of the last Ice Age.24

The rising sea levels were caused by the tumultuous melting of the

icecap which was rapidly retreating everywhere in the northern

hemisphere by around 10,000 BC.25 It is therefore interesting that

at least one ancient map appears to show southern Sweden covered

with remnant glaciers of the kind that must indeed have been

prevalent then in these latitudes.

The remnant glaciers are on

Claudius Ptolemy’s famous Map of the North. Originally compiled in

the second century AD, this remarkable work from the last great

geographer of classical antiquity was lost for hundreds of

years and rediscovered in the fifteenth century.26

23 Ibid., p. 99.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid., p. 164.

26 Ibid., p. 159.

Ptolemy was custodian of the library at Alexandria, which contained

the greatest manuscript collection of ancient times,27 and it was

there that he consulted the archaic source documents that enabled

him to compile his own map.28 Acceptance of the possibility that the

original version of at least one of the charts he referred to could

have been made around 10,000 BC helps us to explain why he shows

glaciers, characteristic of that exact epoch, together with ‘lakes

... suggesting the shapes of present-day lakes, and streams very

much suggesting glacial streams ... flowing from the glaciers into

the lakes.’29

It is probably unnecessary to add that no one on earth in Roman

times, when Ptolemy drew his map, had the slightest suspicion that

ice ages could once have existed in northern Europe. Nor did anyone

in the fifteenth century (when the map was rediscovered) possess

such knowledge. Indeed, it is impossible to see how the remnant

glaciers and other features shown on Ptolemy’s map could have been

surveyed, imagined or invented by any known civilization prior to

our own.

The implications of this are obvious. So, too, are the implications

of another map, the ‘Portolano’ of Iehudi Ibn Ben Zara, drawn in the

year 1487.30 This chart of Europe and North Africa may have been

based on a source even earlier than Ptolemy’s, for it seems to show

glaciers much farther south than Sweden (roughly on the same

latitude as England in fact)31 and to depict the Mediterranean,

Adriatic and Aegean Seas as they might have looked before the

melting of the European ice-cap.32

Sea level would, of course, have

been significantly lower than it is today. It is therefore

interesting, in the case for instance of the Aegean section of the

map, to note that a great many more islands are shown than currently

exist.33 At first sight this seems odd. However, if ten or twelve

thousand years have indeed elapsed since the era when Ibn Ben Zara’s

source map was made, the discrepancy can be simply explained: the

missing islands

must have been submerged by rising sea levels at the end of the last

Ice Age.

27 See Luciano Canfora, The Vanished Library, Hutchinson Radius,

London, 1989

28 Maps, p. 159.

29 Ibid., p. 164.

30 Ibid., p. 171

31 Ibid., pp. 171-2.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid., pp. 176-7.

Once again we seem to be looking at the fingerprints of a vanished

civilization—one capable of drawing impressively accurate maps of

widely separated parts of the earth.

What kind of technology, and what state of science and culture,

would have been required to do a job like that?

Back to

Contents

Chapter 3 -

Fingerprints of a Lost Science

We saw that the Mercator World Map of 1569 included an accurate

portrayal of the coasts of Antarctica as they would have looked

thousands of years ago when they were free of ice. Interestingly

enough, this same map is considerably less accurate in its portrayal

of another region, the west coast of South America, than an earlier

(1538) map also drawn by Mercator.1

The reason for this appears to be that the sixteenth-century

geographer based the earlier map on the ancient sources which we

know he had at his disposal, whereas for the later map he relied

upon the observations and measurements of the first Spanish

explorers of western South America.

Since those explorers had

supposedly brought the latest information back to Europe, Mercator

can hardly be blamed for following them. In so doing the accuracy of

his work declined: instruments capable of finding longitude did not

exist in 1569, but appear to have been used to prepare the ancient

source documents Mercator consulted to produce his 1538 map.2

1 Maps, p. 107.

2 Ibid.

The mysteries of longitude

Let us consider the problem of longitude, defined as the distance in

degrees east or west of the prime meridian. The current

internationally accepted prime meridian is an imaginary curve drawn

from the North Pole to the South Pole passing through the Royal

Observatory at Greenwich, London. Greenwich therefore stands at

0°

longitude while New York, for example, stands at around 74° west,

and Canberra, Australia, at roughly 150° east.

It would be possible to write an elaborate explanation of longitude

and of what needs to be done to fix it precisely for any given point

on the earth’s surface. What we are concerned with here, however, is

not so much technical detail as the accepted historical facts about

humanity’s growing knowledge of the mysteries of longitude.

Among

these facts, this is the most important: until a breakthrough

invention in the eighteenth century, cartographers and navigators

were unable to fix longitude with any kind of precision. They could

only make guesses which were usually inaccurate by many hundreds of

miles, because the technology had not yet been developed to allow

them to do the job properly.

Latitude north or south of the equator did not pose such a problem:

it could be worked out by means of angular measurements of the sun

and stars taken with relatively simple instruments. But to find

longitude equipment of an altogether different and superior calibre

was needed, which could combine position measurements with time

measurements.

Throughout the span of known history the invention of

such equipment had remained beyond the capacities of scientists, but

by the beginning of the eighteenth century, with rapidly increasing

sea traffic, a mood of impatience and urgency had set in. In the

words of an authority on the period,

‘The search for longitude

overshadowed the life of every man afloat, and the safety of every

ship and cargo. Accurate measurement seemed an impossible dream and

“discovering the longitude” had become a stock phrase in the press

like “pigs might fly”.’3

3

Simon Bethon and Andrew Robinson, The Shape of the World: The

Mapping and Discovery of the Earth, Guild Publishing, London, 1991,

p. 117.

What was needed, above all else, was an instrument that would keep

the time (at the place of departure) with perfect accuracy during

long sea journeys despite the motion of the ship and despite the

adverse conditions of alternating heat and cold, wet and dry. ‘Such

a Watch’, as Isaac Newton told the members of the British

government’s official Board of Longitude in 1714, ‘hath not yet been

made’.4

Indeed not. The timepieces of the seventeenth and early eighteenth

centuries were crude devices which typically lost or gained as much

as a quarter of an hour per day. By contrast, an effective marine

chronometer could afford to lose or gain that much only over several

years.5

It was not until the 1720s that the talented English clockmaker John

Harrison began work on the first of a series of designs which

resulted in the manufacture of such a chronometer. His objective was

to win the prize of £20,000 offered by the Board of Longitude ‘for

the inventor of any means of determining a ship’s longitude within

30 nautical miles at the end of a six weeks’ voyage’.6

A chronometer

capable of fulfilling this condition would have to keep time to

within three seconds per day. It took almost forty years, during

which several prototypes were completed and tested, before Harrison

was able to meet these standards. Finally, in 1761, his elegant

Chronometer No. 4 left Britain on board HMS Deptford bound for

Jamaica, accompanied by Harrison’s son William.

Nine days into the

voyage, on the basis of longitude calculations made possible by the

chronometer, William advised the captain that they would sight the

Madeira Islands the following morning. The captain offered five to

one that he was wrong but agreed to hold the course. William won the

bet. Two months later, at Jamaica, the instrument was found to have

lost just five seconds.7

Harrison had surpassed the conditions set by the Board of Longitude.

Thanks to the British government’s bureaucratic dithering, however,

he was not awarded the £20,000 prize money until three years before

his death in 1776. Understandably, it was only when he had the funds

in his hands that he divulged the secrets of his design. As a result

of this delay, Captain James Cook did not have the benefit of a

chronometer when he made his first voyage of discovery in 1768.8

By

the time of his third voyage, however (1778-9), he was able to map

the Pacific with impressive accuracy, fixing not only the correct

latitude but the correct longitude of every island and coastline.9

4 Ibid., p. 121.

5 Ibid., p. 120.

6 Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1991, 3:289.

7 Shape of the World, pp.

123-4.

8 Ibid., p. 125.

9 Ibid., p. 131.

Henceforward, ‘thanks to Cook’s care and Harrison’s chronometer ...

no navigator could have an excuse for failing to find a Pacific

island ... or for being wrecked on a coastline appearing

from nowhere.’10

Indeed, with their accurate longitudes, Cook’s Pacific maps must be

ranked among the very first examples of the precise cartography of

our modern era. They remind us, moreover, that the making of really

good maps requires at least three key ingredients: great journeys of

discovery; first-class mathematical and cartographic skills;

sophisticated chronometers.

It was not until Harrison’s chronometer became generally available

in the 1770s that the third of these preconditions was fulfilled.

This brilliant invention made it possible for cartographers to fix

longitude precisely, something that the Sumerians, the Ancient

Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans, and indeed all other known

civilizations before the eighteenth century were supposedly unable

to do. It is therefore surprising and unsettling to come across

vastly older maps which give latitudes and longitudes with modern

precision.

Precision instruments

These inexplicably precise latitudes and longitudes are found in the

same general category of documents that contain the advanced

geographical knowledge I have outlined.

The Piri Reis Map of 1513, for example, places South America and

Africa in the correct relative longitudes,11 theoretically an

impossible feat for the science of the time. But Piri Reis was

candid in admitting that his map was based on far earlier sources.

Could it have been from one of these sources that he derived his

accurate longitudes?

Also of great interest is the so-called ‘Dulcert Portulano’ of AD

1339 which focuses on Europe and North Africa. Here latitude is

perfect across huge distances and the total longitude of the

Mediterranean and Black Seas is correct to within half a degree.12

Professor Hapgood comments that the maker of the original source

from which the Dulcert Portulano was copied had,

‘achieved highly

scientific accuracy in finding the ratio of latitude to longitude.

He could only have done this if he had precise information on the

relative longitudes of a great many places scattered all the way

from Galway in Ireland to the eastern bend of the Don in Russia.’13

The Zeno Map14 of AD 1380 is another enigma. Covering a vast area of

the north as far as Greenland, it locates a great many widely

scattered places at latitudes and longitudes which are ‘amazingly

correct’.15

10 Ibid.

11 Maps, pp. 1, 41.

12 Ibid., p. 116.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid., pp. 149-58.

15 Ibid, p. 152.

It is

‘unbelievable’, asserts Hapgood, ‘that anyone in the fourteenth

century could have found accurate latitudes for these places, to say

nothing of accurate longitudes’.16

The Oronteus Finaeus World Map also commands attention: it

successfully places the coasts of Antarctica in correct latitudes

and relative longitudes and finds a remarkably accurate area for the

continent as a whole. This reflects a level of geographical

knowledge not available until the twentieth century.17

The Portolano of lehudi Ibn Ben Zara is another map notable for its

accuracy where relative latitudes and longitudes are concerned.18

Total longitude between Gibraltar and the Sea of Azov is accurate to

half a degree, while across the map as a whole average errors of

longitude are less than a degree.19

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid., p. 98.

18 Ibid., p. 170.

19 Ibid., p. 173.

These examples represent only a small fraction of the large and

challenging dossier of evidence presented by Hapgood. Layer upon

layer, the cumulative effect of his painstaking and detailed

analysis is to suggest that we are deluding ourselves when we

suppose that accurate instruments for measuring longitude were not

invented until the eighteenth century.

On the contrary, the Piri

Reis and other maps appear to indicate very strongly that such

instruments were re-discovered then, that they had existed long ages

before and had been used by a civilized people, now lost to history,

who had explored and charted the entire earth. Furthermore, it seems

that these people were capable not only of designing and

manufacturing precise and technically advanced mechanical

instruments but were masters of a precocious mathematical science.

The lost mathematicians

To understand why, we should first remind ourselves of the obvious:

the earth is a sphere. When it comes to mapping it, therefore, only

a globe can represent it in correct proportion. Transferring

cartographic data from a globe to flat sheets of paper inevitably

involves distortions and can be accomplished only by means of an

artificial and complex mechanical and mathematical device known as

map projection.

There are many different kinds of projection. Mercator’s, still used

in atlases today, is perhaps the most familiar. Others are

dauntingly referred to as Azimuthal, Stereographic, Gnomonic,

Azimuthal Equidistant, Cordiform, and so on, but it is unnecessary

to go into this any further here.

We need only note that all

successful projections require

the use of sophisticated mathematical techniques of a kind

supposedly unknown in the ancient world20 (particularly in the

deepest antiquity before 4000 BC when there was allegedly no human

civilization at all, let alone one capable of developing and using

advanced mathematics and geometry).

Charles Hapgood submitted his collection of ancient maps to the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology for evaluation by Professor

Richard Strachan. The general conclusion was obvious, but he wanted

to know precisely what level of mathematics would have been required

to draw up the original source documents. On 18 April 1965 Strachan

replied that a very high level of mathematics indeed would have been

necessary.

Some of the maps, for example, seemed to express ‘a Mercator type projection’ long before the time of Mercator himself.

The relative complexity of this projection (involving latitude

expansion) meant that a trigonometric coordinate transformation

method must have been used.

Other reasons for deducing that the ancient map-makers must have

been skilled mathematicians were as follows:

1 - The determination of

place locations on a continent requires at least geometric

triangulation methods. Over large distances (of the order of 1000

miles) corrections must be made for the curvature of the earth,

which requires some understanding of spherical trigonometry.

2 - The

location of continents with respect to one another requires an

understanding of the earth’s sphericity, and the use of spherical

trigonometry.

3 - Cultures with this knowledge, plus the precision

instruments to make the required measurements to determine location,

would most certainly use their mathematical technology in creating

maps and charts.’21

20 Ibid., p. 225ff.

21 Ibid., p. 228.

Strachan’s impression that the maps, through generations of

copyists, revealed the handiwork of an ancient, mysterious and

technologically advanced civilization, was shared by reconnaissance

experts from the US Airforce to whom Hapgood submitted the evidence.

Lorenzo Burroughs, chief of the 8th Reconnaissance Technical

Squadron’s Cartographic Section at Westover Air Base, made a

particularly close study of the Oronteus Finaeus Map.

He concluded

that some of the sources upon which it was based must have been

drawn up by means of a projection similar to the modern Cordiform

Projection.

This, said Burroughs:

suggests the use of advanced mathematics. Further, the shape given

to the Antarctic Continent suggests the possibility, if not the

probability, that the original source maps were compiled on a

stereographic or gnomonic type of projection involving the use of

spherical trigonometry.

We are convinced that the findings made by you and your associates

are valid, and that they raise extremely important questions

affecting geology and ancient

history ...’22

Hapgood was to make one more important discovery: a Chinese map

copied from an earlier original on to a stone pillar in AD 1137.23

This map incorporates precisely the same kind of high quality

information about longitudes as the others. It has a similar grid

and was drawn up with the benefit of spherical trigonometry. Indeed,

on close examination, it shares so many features with the European

and Middle Eastern maps that only one explanation seems adequate: it

and they must have stemmed from a

common source.24

We seem to be confronted once again by a surviving fragment of the

scientific knowledge of a lost civilization. More than that, it

appears that this civilization must have been at least in some

respects as advanced as our own and that its cartographers had

‘mapped virtually the entire globe with a uniform general level of

technology, with similar methods, equal knowledge of mathematics,

and probably the same sorts of instruments’.25

22 Ibid., pp. 244-5.

23 Ibid., p. 135.

24 Ibid., p. 139.

25 Ibid.,

pp. 139, 145.

The Chinese map also indicates something else: a global legacy must

have been handed down—a legacy of inestimable value, in all

probability incorporating much more than sophisticated geographical

knowledge.

Could it have been some portion of this legacy that was distributed

in prehistoric Peru by the so-called ‘Viracochas’, mysterious

bearded strangers said to have come from across the seas, in a ‘time

of darkness’, to restore civilization after a great upheaval of the

earth?

I decided to go to Peru to see what I could find.

Back to

Contents

or

Continue to

Chapter 4

→

|