|

Part VI

The Giza Invitation

Egypt 1

Chapter 33

-

Cardinal Points

Giza, Egypt, 16 March 1993, 3:30 a.m.

We walked through the deserted lobby of our hotel and stepped into

the white Fiat waiting for us in the driveway outside. It was driven

by a lean, nervous Egyptian named Ali whose job it was to get us

past the guards at the Great Pyramid and away again before sunrise.

He was nervous because if things went wrong Santha and I would be

deported from Egypt and he would go to jail for six months.

Of course, things were not supposed to go wrong. That was why Ali

was with us. The day before we’d paid him 150 US dollars which he

had changed into Egyptian pounds and spread among the guards

concerned. They, in return, had agreed to turn a blind eye to our

presence during the next couple of hours.

We drove to within half a mile of the Pyramid, then walked the rest

of the way—around the side of the steep embankment that looms above

the village of Nazlet-el-Samaan and leads to the monument’s north

face. None of us said very much as we trudged through the soft sand

just out of range of the security lights. We felt excited and

apprehensive at the same time. Ali was by no means certain that his

bribes were going to work.

For a while we stood still in the shadows, gazing at the monstrous

bulk of the Pyramid reaching into the darkness above us and blotting

out the southern stars. Then a patrol of three men armed with

shotguns and wrapped in blankets against the night chill came into

view at the northeastern corner, about fifty yards away, where they

stopped to share a cigarette. Indicating that we should stay put,

Ali stepped forward into the light and walked over to the guards. He

talked to them for several minutes, apparently arguing heatedly.

Finally he beckoned to us, indicating that we should join him.

‘There’s a problem,’ he explained. ‘One of them, the captain here,

[he indicated a short, unshaven, disgruntled looking fellow] is

insisting that we pay an extra thirty dollars otherwise the deal is

off. What do you want to do?’

I fished around in my wallet, counted

out thirty dollars and handed the bills to Ali. He folded them and

passed them to the captain. With an air of aggrieved dignity, the

captain stuffed the money into his shirt pocket, and, finally, we

all shook hands.

‘OK,’ said Ali, ‘let’s go.’

Inexplicable precision

As the guards continued their patrol in a westerly direction along

the northern face of the Great Pyramid, we made our way around the

northeastern corner and along the base of the eastern face.

I had long ago fallen into the habit of orienting myself according

to the monument’s sides. The northern face was aligned, almost

perfectly, to true north, the eastern face almost perfectly to true

east, the southern to true south, and the western face to true west.

The average error was only around three minutes of arc (down to less

than two minutes on the southern face)1—incredible accuracy for any

building in any epoch, and an inexplicable, almost supernatural feat

here in Egypt 4500 years ago when the Great Pyramid was supposed to

have been built.

1 The

Pyramids of Egypt, p. 208

An error of three arc minutes represents an infinitesimal deviation

from true of less than 0.015 per cent. In the opinion of structural

engineers, with whom I had discussed the Great Pyramid, the need for

such precision was impossible to understand.

From their point of

view as practical builders, the expense, difficulty and time spent

achieving it would not have been justified by the apparent results:

even if the base of the monument had been as much as two or three

degrees out of true (an error of say 1 per cent) the difference to

the naked eye would still have been too small to be noticeable. On

the other hand the difference in the magnitude of the tasks required

(to achieve accuracy within three minutes as opposed to three

degrees) would have been immense.

Overview of Giza from the north looking south, with the Great

Pyramid in the foreground.

Obviously, therefore, the ancient master-builders who had raised the

Pyramid at the very dawn of human civilization must have had

powerful motives for wanting to get the alignments with the cardinal

directions just right. Moreover, since they had achieved their

objective with uncanny exactness they must have been highly skilled,

knowledgeable and competent people with access to excellent

surveying and setting-out equipment.

This impression was confirmed

by many of the monument’s other characteristics. For example, its

sides at the base were all almost exactly the same length,

demonstrating a margin of error far smaller than modern architects

would be required to achieve today in the construction of, say, an

average-size office block. This was no office block, however. It was

the Great Pyramid of Egypt, one of the largest structures ever built

by man and one of the oldest. Its north side was 755 feet 4.9818

inches in length; its west side was 755 feet 9.1551 inches in

length; its east side was 755 feet 10.4937 inches; its south side

756 feet 0.9739 inches.2

2

J. H. Cole, Survey of Egypt, paper no. 39: ‘The Determination of the

Exact Size and Orientation of the Great Pyramid of Giza’, Cairo,

1925.

This meant that there was a difference of

less than 8 inches between its shortest and longest sides: an error

amounting to a tiny fraction of 1 per cent on an average side length

of over 9063 inches.

Once again, I knew from an engineering perspective that the bare

figures did not do justice to the enormous care and skill required

to achieve them. I knew, too, that scholars had not yet come up with

a convincing explanation of exactly how the Pyramid builders had

adhered consistently to such high standards of precision.3

3

The conventional explanations, as given in The Pyramids of Egypt,

for example, are entirely unsatisfactory, as Edwards himself admits;

see pp. 85-7, 206-41.

What really interested me, however, was the even bigger

question-mark over another issue:

If they had permitted a margin of error of

1-2 per cent— instead of less than one-tenth of 1 per cent—they

could have simplified their tasks with no apparent loss of quality.

-

Why hadn’t they done so?

-

Why had they insisted on making everything

so difficult?

-

Why, in short, in a supposedly ‘primitive’ stone

monument built more than 4500 years ago were we seeing this strange, obsessional adherence to machine-age standards of precision?

Black hole in history

Our plan was to climb the Great Pyramid—something that had been

strictly illegal since 1983 when the messy falls of several

foolhardy tourists had forced the government of Egypt to impose a

ban. I realized that we were being foolhardy too (particularly in

attempting the climb at night) and I didn’t feel good about breaking

what was basically a sensible law. By this stage, however, my

intense interest in the Pyramid, and my desire to learn everything I

could about it, had over-ridden my common sense.

Now, after parting company with the guard patrol at the

north-eastern corner of the monument, we continued to make our way

surreptitiously along the eastern face towards the south-eastern

corner.

There were dense shadows among the twisted and broken paving stones

that separated the Great Pyramid from the three much smaller

‘subsidiary’ pyramids lying immediately to its east. There were also

three deep and narrow rock-cut pits which resembled giant graves.

These had been found empty by the archaeologists who had excavated

them, but were shaped as though they had been intended to enclose

the hulls of high-prowed, streamlined boats.

Roughly halfway along the Pyramid’s eastern face we encountered

another patrol. This time it consisted of two guards, one of whom

must have been eighty years old. His companion, a teenager with

pustulant acne, informed us that the money Ali had paid was

insufficient and that fifty more Egyptian pounds would be required

if we were to proceed. I already had the notes in my hand and gave

them to the lad without delay. I was past caring how much this was

costing; I just wanted to make the climb and get down and away

before dawn without being arrested.

We walked on, reaching the south-eastern corner at a little after

4:15

a.m.

Very few modern buildings, even the houses we live in, have corners

that consist of perfect ninety degree right angles; it is common for

them to be a degree or more out of true. It doesn’t make any

difference structurally and nobody notices such minute errors. In

the case of the Great Pyramid, however, I knew that the ancient

master-builders had found a way to narrow the margin of error to

almost nothing.

Thus, while falling short of the perfect ninety

degrees, the south-eastern corner achieved an impressive 89° 56’

27”. The north-eastern corner measured 90° 3’ 2”; the southwestern

90° 0’ 33”, and the north-western was just two seconds of a degree

out of true at 89° 59’ 58”.4

4 Ibid., p. 87.

This was, of course, extraordinary. And like almost everything else

about the Great Pyramid it was also extremely difficult to explain.

Such accurate building techniques—as accurate as the best we have

today— could have evolved only after thousands of years of

development and experimentation. Yet there was no evidence that any

process of this kind had ever taken place in Egypt. The Great

Pyramid and its neighbors at Giza had emerged out of a black hole

in architectural history so deep and so wide that neither its bottom

nor its far side had ever been identified.

Ships in the desert

Guided by the increasingly perspiring Ali, who had not yet explained

why it was necessary for us to circumnavigate the Pyramid before

climbing it, we now began to make our way in a westerly direction

along the monument’s southern side. Here there were two further

boat-shaped pits, one of which, although still sealed, had been

investigated with fibre-optic cameras and was known to contain a

high-prowed sea-going vessel more than 100 feet long. The other pit

had been excavated in the 1950s. Its contents—an even larger

seagoing vessel, a full 141 feet in length5—had been placed in the

so-called Boat Museum, an ugly modern structure that gangled on

stilts beneath the south face of the Pyramid.

Made of cedarwood, the beautiful ship in the museum was still in

perfect condition 4500 years after it had been built. With a

displacement of around 40 tons, its design was particularly

thought-provoking, incorporating, in the words of one expert,

‘all

the sea-going ship’s characteristic properties, with prow and stern

soaring upward, higher than in a Viking ship, to ride out the

breakers and high seas, not to contend with the little ripples of

the Nile.’6

5

See Lionel Casson, Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times, University

of Texas Press, 1994, p. 17; The Ra Expeditions, p. 15.

6 The Ra

Expeditions, p. 17.

Another authority felt that the careful and clever design of this

strange pyramid boat could potentially have made it ‘a far more

seaworthy craft than anything available to Columbus’.7 Moreover, the

experts agreed that it had been built to a pattern that could only

have been ‘created by shipbuilders from a people with a long, solid

tradition of sailing on the open sea.’ 8

Present at the very beginning of Egypt’s 3000-year history, who had

those as yet unidentified shipbuilders been? They had not

accumulated their ‘long, solid tradition of sailing on the open sea’

while ploughing the fields of the landlocked Nile Valley. So where

and when had they developed their maritime skills?

There was yet another puzzle. I knew that the Ancient Egyptians had

been very good at making scale models and representations of all

manner of things for symbolic purposes.9 I therefore found it hard

to understand why they would have gone to the trouble of

manufacturing and then burying a boat as big and sophisticated as

this if its only function, as the Egyptologists claimed, had been as

a token of the spiritual vessel that would carry the soul of the

deceased king to heaven.10

That could have been achieved as

effectively with a much smaller craft, and only one would have been

needed, not several. Logic therefore suggested that these gigantic

vessels might have been intended for some other purpose altogether,

or had some quite different and still unsuspected symbolic

significance ...

We had reached the rough midpoint of the southern face of the Great

Pyramid when we at last realized why we were being taken on this

long walkabout. The objective was for us to be relieved of moderate

sums of money at each of the four cardinal points. The tally thus

far was 30 US dollars at the northern face and 50 Egyptian pounds at

the eastern face. Now I shelled out a further 50 Egyptian pounds to

yet another patrol Ali was supposed to have paid off the day before.

‘Ali,’ I hissed, ‘when are we going to climb the Pyramid?’

‘Right away, Mr. Graham,’ our guide replied. He walked confidently

forward, gesturing directly ahead, then added, ‘We shall ascend at

the south-west corner ...’

7 Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, pp. 132-3.

8 The Ra Expeditions,

p. 16.

9

See, for example, Christine Desroches-Noblecourt, Tutankhamen,

Penguin Books, London, 1989, pages 89, 108, 113, 283.

10 A.J.

Spencer, The Great Pyramid Fact Sheet, P.J. Publications, 1989.

Back to

Contents

Chapter 34

-

Mansion of Eternity

Have you ever climbed a pyramid, at night, fearful of arrest, with

your nerves in shreds?

It’s a surprisingly difficult thing to do, especially where the

Great Pyramid is concerned. Even though its top 31 feet are no

longer intact, its presently exposed summit platform still stands

more than 450 feet above ground level.1 It consists, moreover, of

203 separate courses of masonry, with the average course height

being about two and a quarter feet.2

1 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 8.

2

Peter Lemesurier, The Great Pyramid: Your Personal Guide, Element

Books, Shaftesbury, 1987, p. 225.

Averages do not tell you everything, as I discovered soon after we

began the climb. The courses turned out to be of unequal depth, some

barely reaching knee level while others came up almost to my chest

and created formidable obstacles. At the same time the horizontal

ledges between each of the steps were very narrow, often only a

little wider than my foot, and many of the big limestone blocks,

which had looked so solid from below, proved to be crumbling and

broken.

Somewhere around 30 courses up Santha and I began to appreciate what

we had let ourselves in for. Our muscles were aching and our knees

and fingers stiff and bruised—yet we were barely one-seventh of the

way to the summit and there were still more than 170 courses to

climb. Another worry was the vertiginous drop steadily opening

beneath us.

Looking down along the ruptured contours that marked the

line of the southwestern corner, I was taken aback to see how far we

had already climbed and experienced a momentary, giddying

presentiment of how easy it would be for us to fall, head over heels

like Jack and Jill, bouncing and jolting over the huge layers of

stone, breaking our crowns at the bottom.

Ali had permitted a pause of a few moments for us to catch our

breaths, but now he signalled that we should press on and began to

climb again. Still using the corner as a guideline, he rapidly

disappeared into the darkness above.

Somewhat less confidently, Santha and I followed.

Time and motion

The 35th course of masonry was a hard one to clamber over, being

made of particularly massive blocks, much larger than any of the

others we had

so far encountered (except those at the very base) and estimated to

weigh between 10 and 15 tons apiece.3

This contradicted engineering

logic and commonsense, both of which called for a progressive

decrease in the size and weight of the blocks that had to be

transported to the summit as the pyramid rose ever higher. Courses

1-18, which diminished from a height of about 55.5 inches at ground

level to just over 23 inches at course 17, did obey this rule.

Then

suddenly, at course 19, the block height rose again to almost 36

inches. At the same time the other dimensions of the blocks also

increased and their weight grew from the relatively manoeuvrable

range of 2-6 tons that was common in the first 18 courses to the

more ponderous and cumbersome range of 10-15 tons.4 These,

therefore, were really big monoliths that had been carved out of

solid limestone and raised more than 100 feet into the air before

being placed faultlessly in position.

To have worked effectively the pyramid builders must have had nerves

of steel, the agility of mountain goats, the strength of lions and

the confidence of trained steeplejacks. With the cold morning wind

whipping around my ears and threatening to launch me into flight, I

tried to imagine what it must have been like for them, poised

dangerously at this (and much higher) altitudes, lifting,

manoeuvring and positioning exactly an endless production line of

chunky limestone monoliths—the smallest of which weighed as much as

two modern family cars.

How long had the pyramid taken to complete? How many men had worked

on it? The consensus among Egyptologists was two decades and 100,000

men.5 It was also generally agreed that the construction project had

not been a year-round affair but had been confined (through labour

force availability) to the annual three-month agricultural lay-off

season imposed by the flooding of the Nile.6

As I continued to climb, I reminded myself of the implications of

all this. It wasn’t just the tens of thousands of blocks weighing 15

tons or more that the builders would have had to worry about. Year

in, year out, the real crises would have been caused by the millions

of ‘average-sized’ blocks, weighing say 2.5 tons, that also had to

be brought to the working plane. The Pyramid has been reliably

estimated to consist of a total of 2.3 million blocks.7

3

Dr. Joseph Davidovits and Margie Morris, The Pyramids: An Enigma

Solved, Dorset Press, New York, 1988, pp. 39-40.

4 Ibid., p. 37.

5

John Baines and Jaromir Malek, Atlas of Ancient Egypt, Time-Life

Books, Virginia, 1990,

p. 160; The Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 229-30.

6 The Pyramids of Egypt,

p. 229.

7 Ibid., p. 85.

Assuming

that the masons worked ten hours a day, 365 days a year, the

mathematics indicate that they would have needed to place 31 blocks

in position every hour (about one block every two minutes) to

complete the Pyramid in twenty years. Assuming that construction

work had been confined to the annual three-month lay-off,

the problems multiplied: four blocks a minute would have had to be

delivered, about 240 every hour.

Such scenarios are, of course, the stuff construction managers’

nightmares are made of. Imagine, for example, the daunting degree of

coordination that must have been maintained between the masons and

the quarries to ensure the requisite rate of block flow across the

production site. Imagine also the havoc if even a single 2.5 ton

block had been dropped from, say, the 175th course.

The physical and managerial obstacles seemed staggering on their

own, but beyond these was the geometrical challenge represented by

the pyramid itself, which had to end up with its apex positioned

exactly over the centre of its base. Even the minutest error in the

angle of incline of any one of the sides at the base would have led

to a substantial misalignment of the edges at the apex. Incredible

accuracy, therefore, had to be maintained throughout, at every

course, hundreds of feet above the ground, with great stone blocks

of killing weight.

Rampant stupidity

How had the job been done?

At the last count there were more than thirty competing and

conflicting theories attempting to answer that question. The

majority of academic Egyptologists have argued that ramps of one

kind or another must have been used. This was the opinion, for

example, of Professor I.E.S Edwards, a former keeper of Egyptian

Antiquities at the British Museum who asserted categorically:

‘Only

one method of lifting heavy weights was open to the ancient

Egyptians, namely by means of ramps composed of brick and earth

which sloped upwards from the level of the ground to whatever height

was desired.’8

John Baines, professor of Egyptology at Oxford University, agreed

with Edwards’s analysis and took it further:

‘As the pyramid grew in

height, the length of the ramp and the width of its base were

increased in order to maintain a constant gradient (about 1 in 10)

and to prevent the ramp from collapsing. Several ramps approaching

the pyramid from different sides were probably used.’9

To carry an inclined plane to the top of the Great Pyramid at a

gradient of 1:10 would have required a ramp 4800 feet long and more

than three times as massive as the Great Pyramid itself (with an

estimated volume of 8 million cubic meters as against the Pyramid’s

2.6 million cubic meters).10

8 Ibid., p. 220.

9 Atlas of Ancient Egypt, p. 139.

10

Peter Hodges and Julian Keable, How the Pyramids Were Built, Element

Books, Shaftesbury, 1989, p. 123.

Heavy weights could not have been

dragged up any gradient

steeper than this by any normal means.11 If a lesser gradient had

been chosen, the ramp would have had to be even more absurdly and

disproportionately massive.

The problem was that mile-long ramps reaching a height of 480 feet

could not have been made out of ‘bricks and earth’ as Edwards and

other Egyptologists supposed. On the contrary, modern builders and

architects had proved that such ramps would have caved in under

their own weight if they had consisted of any material less costly

and less stable than the limestone ashlars of the Pyramid itself.12

Since this obviously made no sense (besides, where had the 8 million

cubic meters of surplus blocks been taken after completion of the

work?), other Egyptologists had proposed the use of spiral ramps

made of mud brick and attached to the sides of the Pyramid. These

would certainly have required less material to build, but they would

also have failed to reach the top.13

They would have presented

deadly and perhaps insurmountable problems to the teams of men

attempting to drag the big blocks of stone around their hairpin

corners. And they would have crumbled under constant use. Most

problematic of all, such ramps would have cloaked the whole pyramid,

thus making it impossible for the architects to check the accuracy

of the setting-out during building.14

But the pyramid builders had checked the accuracy of the setting

out, and they had got it right, because the apex of the pyramid was

poised exactly over the centre of the base, its angles and its

corners were true, each block was in the correct place, and each

course had been laid down level—in near-perfect symmetry and with

near-perfect alignment to the cardinal points.

Then, as though to

demonstrate that such tours-de-force of technique were mere trifles,

the ancient master-builders had gone on to play some clever

mathematical games with the monument’s dimensions, presenting us,

for example, as we saw in Chapter Twenty-three, with an accurate use

of the transcendental number pi in the ratio of its height to its

base perimeter.15 For some reason, too, it had taken their fancy to

place the Great Pyramid almost exactly on the 30th parallel at

latitude 29° 58’ 51”.

11 Ibid., p. 11.

12 Ibid., p. 13.

13

Ibid., p. 125-6. Failure to reach the top would be because spiral

ramps and linked scaffolds overlap and exceed the space available

long before arrival at the summit.

14 Ibid., p. 126.

15

See Chapter Twenty-three; The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 219; Atlas of

Ancient Egypt, p. 139.

This, as a former astronomer royal of Scotland

once observed, was ‘a sensible defalcation from 30°’, but not

necessarily in error:

For if the original designer had wished that men should see with

their body, rather than their mental eyes, the pole of the sky from

the foot of the Great Pyramid, at an altitude before them of 30°, he

would have had to take account of the refraction of the atmosphere;

and that would have necessitated the building standing not at

30° but at 29° 58’ 22”.16

16

Piazzi Smyth, The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed,

Bell Publishing Company, New York, 1990, p. 80.

Compared to the true position of 29° 58’ 51”, this was an error of

less than half an arc minute, suggesting once again that the

surveying and geodetic skills brought to bear here must have been of

the highest order.

Feeling somewhat overawed, we climbed on, past the 44th and 45th

courses of the hulking and enigmatic structure. At the 40th course

an angry voice hailed us in Arabic from the plaza below and we

looked down to see a tiny, turbaned man dressed in a billowing

kaftan. Despite the range, he had unslung his shotgun and was

preparing to take aim at us.

The guardian and the vision

He was, of course, the guardian of the Pyramid’s western face, the

patrolman of the fourth cardinal point, and he had not received the

extra funds dispensed to his colleagues of the north, east and south

faces.

I could tell from Ali’s perspiration that we were in a potentially

tricky situation. The guard was ordering us to come down at once so

that he could place us under arrest.

‘This, however, could probably

be avoided with a further payment,’ Ali explained.

I groaned. ‘Offer him 100 Egyptian pounds.’

‘Too much,’ Ali cautioned, ‘it will make the others resentful. I

shall offer him 50.’

More words were exchanged in Arabic. Indeed, over the next few

minutes, Ali and the guard managed to have quite a sustained

conversation up and down the south-western corner of the Pyramid at

4:40 in the morning. At one point a whistle was blown. Then the

guards of the southern face put in a brief appearance and stood in

conference with the guard of the western face, who had now also been

joined by the two other members of his patrol.

Just when it seemed that Ali had lost whatever argument he was

having on our behalf, he smiled and heaved a sigh of relief.

‘You

will pay the extra 50 pounds when we have returned to the ground,’

he explained. ‘They’re letting us continue but they say that if any

senior officer comes along and sees us they will not be able to help

us.’

We struggled upwards in silence for the next ten minutes or so until

we had reached the tooth course—roughly the halfway mark and already

well over 250 feet above the ground. We gazed over our shoulders to

the southwest, where a once-in-a-lifetime vision of staggering

beauty and power confronted us. The crescent moon, which hung low in

the sky to the south-east, had emerged from behind a scudding cloud

bank and projected its ghostly radiance directly at the northern and

eastern faces of the neighbouring Second Pyramid, supposedly built

by the Fourth

Dynasty Pharaoh Khafre (Chephren).

This stunning monument, second

only in size and majesty to the Great Pyramid itself (being just a

few feet shorter and 48 feet narrower at the base) appeared lit up,

as though energized from within, by a pale and unearthly fire.

Behind it in the distance, slightly offset among the dark desert

shadows, was the smaller Pyramid of Menkaure (Mycerinus), measuring

356 feet along each side and some 215 feet in height.17

17 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 125.

For a moment, against the glittering backdrop of the inky

sky, experienced the illusion of being in motion, of standing at the

stern of some great ship of the heavens and looking back at two

other vessels which seemed to follow in my wake, strung out in

battle order behind me.

-

So where was this convoy going, this squadron of pyramids?

-

And were

the prodigious structures all the work of megalomaniac pharaohs, as

the Egyptologists believed?

-

Or had they been designed by mysterious

hands to voyage eternally through time and space towards some as yet

unidentified objective?

From this altitude, though the southern sky was partially occluded

by the vast bulk of the Pyramid of Khafre, I could see all the

western sky as it arched down from the celestial north pole towards

the distant rim of the revolving planet. Polaris, the Pole Star, was

far to my right, in the constellation of the Little Bear. Low on the

horizon, about ten degrees north of west, Regulus, the paw-star of

the imperial constellation of Leo, was about to set.

Under Egyptian skies

Just above the 150th course, Ali hissed at us to keep our heads

down. A police car had come into view around the north-western

corner of the Great Pyramid and was now proceeding along the western

flank of the monument with its blue light slowly flashing.

We stayed

motionless in the shadows until the car had passed. Then we began to

climb again, with a renewed sense of urgency, heading as fast as we

could towards the summit, which we now imagined we could see jutting

out above the misty predawn haze.

For what seemed like five minutes we climbed without stopping. When

I looked up, however, the top of the Pyramid still seemed as far

away as ever. We climbed again, panting and sweating, and once again

the summit drew back before us like some legendary Welsh peak. Then,

just when we’d resigned ourselves to an endless succession of such

disappointments, we found ourselves at the top, under a breathtaking

canopy of stars, more than 450 feet above the surrounding plateau on

the most extraordinary viewing platform in the world.

To our north

and east, sprawled out across the wide, sloping valley of the River

Nile, lay the

city of Cairo, a jumble of skyscrapers and flat traditional roofs

separated by the dark defiles of narrow streets and interspersed

with the needlepoint minarets of a thousand and one mosques. A film

of reflected street-lighting shimmered over the whole scene, closing

the eyes of modern Cairenes to the wonder of the stars but at the

same time creating the hallucination of a fairyland illuminated in

greens and reds and blues and sulphurous yellows.

I felt privileged to witness this strange, electronic mirage from

such an incredible vantage point, perched on the summit platform of

the last surviving wonder of the ancient world, hovering in the sky

over Cairo like Aladdin on his magic carpet.

Not that the 203rd course of the Great Pyramid of Egypt could be

described as a carpet! Measuring just under 30 feet on each side (as

against the monument’s side length of around 755 feet at the base)

it consisted of several hundred waist-high limestone blocks, each of

which weighed about five tons. The course was not completely level:

a few blocks were missing or broken, and rising towards the southern

end there were the substantial remains of about half an additional

step of masonry.

Moreover, at the very centre of the platform,

someone had arranged for a triangular wooden scaffold to be erected,

through the middle of which rose a thick pole, just over 31 feet

long, which marked the monument’s original true height of 481.3949

feet.18 Beneath this a scrawl of graffiti had been carved into the

limestone by generations of tourists.19

18 Ibid., p. 87.

19

‘One is irritated by the number of imbeciles’ names written

everywhere,’ Gustave Flaubert commented in his Letters From Egypt.

‘On the top of the Great Pyramid there is a certain Buffard, 79 rue

St Martin, wallpaper manufacturer, in black letters.’

The complete ascent of the Pyramid had taken us about half an hour

and it was now just after 5 a.m., the time of morning worship.

Almost in unison, the voices of a thousand and one muezzins rang out

from the balconies of the minarets of Cairo, calling the faithful to

prayer and reaffirming the greatness, the indivisibility, the mercy

and the compassion of God. Behind me, to the south-west, the top 22

courses of Khafre’s Pyramid, still clad with their original facing

stones, seemed to float like an iceberg on the ocean of moonlight.

Knowing that we could not stay long in this bewitching place, I sat

down and gazed around at the heavens. Over to the west, across

limitless desert sands, Regulus had now set beneath the horizon, and

the rest of the lion’s body was poised to follow. The constellations

of Virgo and Libra were also dropping lower in the sky and, much

farther to the north, I could see the Great and Little Bears slowly

pacing out their eternal cycle around the celestial pole.

I looked south-east across the Nile Valley and there was the

crescent moon still spreading its spectral radiance from the bank of

the Milky Way.

Following the course of the celestial river, I looked due south:

there, crossing the meridian, was the resplendent constellation of

Scorpius dominated by the first-magnitude star Antares—a red

supergiant 300 times the diameter of the sun. North-east, above

Cairo, sailed Cygnus the swan, his tail feathers marked by Deneb, a

blue-white supergiant visible to us across more than 1800 light

years of interstellar space. Last but not least, in the northern

sky, the dragon Draco coiled sinuously among the circumpolar stars.

Indeed, 4500 years ago, when the Great Pyramid was

supposedly being

built for the Fourth Dynasty Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops), one of the

stars of Draco had stood close to the celestial north pole and had

served as the Pole Star. This had been alpha Draconis, also known as

Thuban. With the passing of the millennia, however, it had gradually

been displaced from its position by the remorseless celestial mill

of the earth’s axial precession so that the Pole Star today is

Polaris in the Little Bear.20

20 Skyglobe 3.6.

I lay back, cushioned my head in my hands and gazed directly up

towards the zenith of heaven. Through the smooth cold stones I

rested on, I thought I could sense beneath me, like a living force,

the stupendous gravity and mass of the pyramid.

Thinking like giants

Covering a full 13.1 acres at the base, it weighed about six million

tons— more than all the buildings in the Square Mile of the City of

London added together,21 and consisted, as we have seen, of roughly

2.3 million individual blocks of limestone and granite. To these had

once been added a 22-acre, mirror-like cladding consisting of an

estimated 115,000 highly polished casing stones, each weighing 10

tons, which had originally covered all four of its faces.22

After being shaken loose by a massive earthquake in AD 1301, the

majority of the facing blocks had subsequently been removed for the

construction of Cairo.23 Here and there around the base, however, I

knew that enough had remained in position to permit the great

nineteenth century archaeologist, W.M. Flinders Petrie, to carry out

a detailed study of them.

21 How the Pyramids Were Built, p. 4-5.

22 Secrets of the Great

Pyramid, pp. 232, 244.

23 Ibid., p. 17.

He had been stunned to encounter

tolerances of less than one-hundredth of an inch and cemented joints

so precise and so carefully aligned that it was impossible to slip

even the fine blade of a pocket knife between them.

‘Merely to place

such stones in exact contact would be careful work’, he admitted,

‘but to do so with cement in the joint seems almost impossible; it

is to be compared to the finest opticians’ work on a

scale of acres.’24

Of course, the jointing of the casing stones was by no means the

only ‘almost impossible’ feature of the Great Pyramid. The

alignments to true north, south, east and west were ‘almost

impossible’, so too were the near- perfect ninety-degree corners,

and the incredible symmetry of the four enormous sides. And so were

the engineering logistics of raising millions of huge stones

hundreds of feet in the air ...

Whoever they had been, therefore, the architects, engineers and

stonemasons who had designed and successfully built this stupendous

monument must indeed have ‘thought like men 100 feet tall’, as

Jean-François Champollion, the founder of modern Egyptology, had

once observed.

He had seen clearly what generations of his

successors were to close their eyes to: that the pyramid builders

could only have been men of giant intellectual stature. Beside the

Egyptians of old, he had added, ‘we in Europe are but

Lilliputians.’25

24 Cited in Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p. 90.

25 Ibid., p. 40. Champollion of course, deciphered the Rosetta Stone.

Back to

Contents

Chapter 35 -

Tombs and Tombs Only?

Climbing down the Great Pyramid was more nerve wracking than

climbing up. We were no longer struggling against the force of

gravity, so the physical effort was less. But the possibilities of a

fatal fall seemed greatly magnified now that our attention was

directed exclusively towards the ground rather than the heavens. We

picked our way with exaggerated care towards the base of the

enormous mountain of stone, sliding and slithering among the

treacherous masonry blocks, feeling as though we had been reduced to

ants.

By the time we had completed the descent the night was over and the

first wash of pale sunlight was filtering into the sky. We paid the

50 Egyptian pounds promised to the guard of the pyramid’s western

face and then, with a tremendous sense of release and exultation, we

walked jauntily away from the monument in the direction of the

Pyramid of Khafre, a few hundred meters to the south-west.

Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure ... Cheops, Chephren, Mycerinus.

Whether

they were referred to by their Egyptian or their Greek names, the

fact remained that these three pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty

(2575-2467 BC) were universally acclaimed as the builders of the Giza pyramids. This had been the case at least since Ancient

Egyptian tour guides had told the Greek historian Herodotus that the

Great Pyramid had been built by Khufu.

Herodotus had incorporated

this information into the oldest surviving written description of

the monuments, which continued:

Cheops, they said, reigned for fifty years, and on his death the

kingship was taken over by his brother Chephren. He also made a

pyramid ... it is forty feet lower than his brother’s pyramid, but

otherwise of the same greatness ... Chephren reigned for fifty-six

years ... then there succeeded Mycerinus, the son of Cheops ... This

man left a pyramid much smaller than his father’s.1

1

Herodotus, The History (translated by David Grene), University of

Chicago Press, 1987, pp. 187-9.

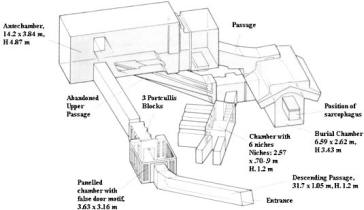

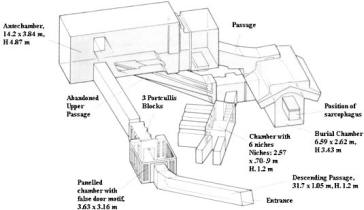

Site plan of the Giza necropolis

Herodotus saw the monuments in the fifth century BC, more than 2000

years after they had been built. Nevertheless it was largely on the

foundation of his testimony that the entire subsequent judgment of

history was based. All other commentators, up to the present,

continued uncritically to follow in the Greek historian’s footsteps.

And down the ages—although it had originally been little more than

hearsay—the attribution of the Great Pyramid to Khufu, the Second

Pyramid to Khafre and the Third Pyramid to Menkaure had assumed the

stature of unassailable fact.

Trivializing the mystery

Having parted company with Ali, Santha and I continued our walk into

the desert. Skirting the immense south-western corner of the Second

Pyramid, our eyes were drawn towards its summit. There we noted

again the intact facing stones that still covered its top 22

courses.

We also noticed that the first few courses above its base,

each of which had a ‘footprint’ of about a dozen acres, were

composed of truly massive blocks of limestone, almost too high to

clamber over, which were about 20 feet long and 6 feet thick. These

extraordinary monoliths, as I was later to discover, weighed 200

tons apiece and belonged to a distinct style of masonry to be found

at several different and widely scattered locations within the Giza

necropolis.

On its north and west sides the Second Pyramid sat on a level

platform cut down out of the surrounding bedrock and was thus

enclosed within a wide trench more than 15 feet deep in places.

Walking due south, parallel to the monument’s scarred western flank,

we picked our way along the edge of this trench towards the much

smaller Third Pyramid, which lay some 400 metres ahead of us in the

desert.

Khufu ... Khafre ... Menkaure ... According to all orthodox

Egyptologists the pyramids had been built as tombs—and only as

tombs—for these three pharaohs.

Yet there were some obvious

difficulties with such assertions. For example, the spacious burial

chamber of the Khafre Pyramid was empty when it was opened in 1818

by the European explorer Giovanni Belzoni. Indeed, more than empty,

the chamber was starkly, austerely bare.

The polished granite

sarcophagus which lay embedded in its floor had also been found

empty, with its lid broken into two pieces nearby.2 How was this to

be explained?

To Egyptologists the answer seemed obvious. At some early date,

probably not many hundreds of years after Khafre’s death, tomb

robbers must have penetrated the chamber and cleared all its

contents including the mummified body of the pharaoh.

Much the same thing seemed to have happened at the smaller Third

Pyramid, towards which Santha and I were now walking—that attributed

to Menkaure. Here the first European to break in had been a British

colonel, Howard Vyse, who had entered the burial chamber in 1837. He

found an empty basalt sarcophagus, an anthropoid coffin lid made of

wood, and some bones. The natural assumption was that these were the

remains of Menkaure.

Modern science had subsequently proved,

however, that the bones and coffin lid dated from the early

Christian era, that is, from 2500 years after the Pyramid Age, and

thus represented the ‘intrusive burial’ of a much later individual

(quite a common practice throughout Ancient Egyptian history).

As to

the basalt sarcophagus—well, it could have belonged to Menkaure.

Unfortunately, however, nobody had the opportunity to examine it

because it had been lost at sea when the ship on which Vyse sent it

to England had sunk off the coast of Spain.3 Since it was a matter

of record that the sarcophagus had been found empty by Vyse, it was

once again assumed that the body of the pharaoh must have been

removed by tomb robbers.

A similar assumption had been made about the body of Khufu, which

was also missing. Here the scholarly consensus, expressed as well as

anyone by George Hart of the British Museum, was that ‘no later than

500 years after Khufu’s funeral’ robbers had forced their way into

the Great Pyramid ‘to steal the burial treasure’.4

2 The Riddle of the Pyramids, p. 54.

3 Ibid., p. 55.

4 George Hart, Pharaohs and Pyramids, Guild Publishing, London,

1991, p. 91.

The implication

is that this incursion must have occurred by or before 2000 BC—since Khufu is

believed to have died in 2528 BC.5 Moreover it was assumed by

Professor

I.E.S Edwards, a leading authority on these matters, that the burial

treasure had been removed from the famous inner sanctum now known as

the King’s Chamber and that the empty ‘granite sarcophagus’ which

stood at the western end of that sanctum had ‘once contained the

King’s body, probably enclosed within an inner coffin made of

wood’.6

All this is orthodox, mainstream, modern scholarship, which is

unquestioningly accepted as historical fact and taught as such at

universities everywhere.7

But suppose it isn’t fact.

5 Atlas of Ancient Egypt, p. 36.

6 The Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 94-5.

7

The Pyramids of Egypt by Professor I. E. S. Edwards is the standard

text on the pyramids.

The cupboard was bare

The mystery of the missing mummy of Khufu begins with the records of

Caliph Al-Ma’mun, a Muslim governor of Cairo in the ninth century

AD. He had engaged a team of quarriers to tunnel their way into the

pyramid’s northern face, urging them on with promises that they

would discover treasure.

Through a series of lucky accidents

‘Ma’mun’s Hole’, as archaeologists now refer to it, had joined up

with one of the monument’s several internal passageways, the

‘descending corridor’ leading downwards from the original concealed

doorway in the northern face (the location of which, though known in

classical times, had been forgotten by Ma’mun’s day).

By a further

lucky accident the vibrations that the Arabs had caused with their

battering rams and drills dislodged a block of limestone from the

ceiling of the descending corridor. When the socket from which it

had fallen was examined it was found to conceal the opening to

another corridor, this time ascending into the heart of the pyramid.

There was a problem, however. The opening was blocked by a series of

enormous plugs of solid granite, clearly contemporaneous with the

construction of the monument, which were held in place by a

narrowing of the lower end of the corridor.8

8 W. M.

Flinders Petrie, The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh (New and Revised

Edition), Histories and Mysteries of Man Ltd., London, 1990,

p. 21.

The quarriers were

unable either to break or to cut through the plugs. They therefore

tunnelled into the slightly softer limestone surrounding them and,

after several weeks of backbreaking toil, rejoined the ascending

corridor higher up—having bypassed a formidable obstacle never

before breached.

The implications were obvious. Since no previous treasure-seekers

had penetrated this far, the interior of the pyramid must still be

virgin territory. The diggers must have licked their lips with

anticipation at the

immense quantities of gold and jewels they could now expect to find.

Similarly—though perhaps for different reasons, Ma’mun must have

been impatient to be the first into any chambers that lay ahead.

It

was reported that his primary motive in initiating this

investigation had not been an ambition to increase his vast personal

wealth but a desire to gain access to a storehouse of ancient wisdom

and technology which he believed to lie buried within the monument.

In this repository, according to age-old tradition, the pyramid

builders had placed,

‘instruments of iron and arms which rust not,

and glasse which might be bended and yet not broken, and strange

spells ...’9

9 John Greaves, Pyramidographia, cited in Serpent in the Sky, p.

230.

The Great Pyramid: entrance and plugging blocks in the ascending

corridor.

The Great Pyramid: detail of corridors, shafts and chambers.

But Ma’mun and his men found nothing, not even any down-to-earth

treasure—and certainly not any high-tech, anachronistic plastic or

instruments of iron or rustproof weapons ... or strange spells

either.

The erroneously named ‘Queen’s Chamber’ (which lay at the end a long

horizontal passageway that branched off from the ascending corridor)

turned out to be completely empty—just a severe, geometrical room.10

More disappointing still, the King’s Chamber (which the Arabs

reached after climbing the imposing Grand Gallery) also offered

little of interest. Its only furniture was a granite coffer just big

enough to contain the body of a man. Later identified, on no very

good grounds, as a ‘sarcophagus’, this undecorated stone box was

approached with trepidation by Ma’mun and his team, who found it to

be lidless and as empty as everything else in the pyramid.11

10 Secrets of the Great Pyramid, p. 11.

11 The Traveller’s Key to

Ancient Egypt, p. 120.

-

Why, how and when exactly had the Great Pyramid been emptied of its

contents?

-

Had it been 500 years after Khufu’s death, as the

Egyptologists suggested?

-

Or was it not more likely, as the evidence

was beginning to suggest, that the inner chambers of the pyramid had

been empty all along, from the very beginning, that is, from the day

that the monument had originally been sealed?

Nobody, after all, had

reached the upper part of the ascending corridor before Ma’mun and

his men. And it was certain, too, that nobody had cut through the

granite plugs blocking the entrance to that corridor.

Commonsense ruled out the possibility of any earlier

incursion—unless there was another way in.

Bottlenecks in the well-shaft

There was another way in.

Farther down the descending corridor, more than 200 feet beyond the

point where the plugged end of the ascending corridor had been

found, lies the concealed entrance to another secret passageway,

deep within the subterranean bedrock of the Giza plateau. If Ma’mun

had discovered this passageway, he could have saved himself a great

deal of trouble, since it provided a readymade route around the

plugs blocking the ascending corridor.

His attention, however, had

been distracted by the challenge of tunnelling past those plugs, and

he made no effort to investigate the lower reaches of the descending

corridor (which he ended up using as a dump for the tons of stone

his diggers removed from the core of the pyramid).12

The full extent of the descending corridor was, however, well-known

and explored in classical times. The Graeco-Roman geographer Strabo

left quite a clear description of the large subterranean chamber it

debouched into (at a depth of almost 600 feet below the apex of the

pyramid).13 Graffiti from the period of the Roman occupation of

Egypt was also found inside this underground chamber, confirming

that it had once been regularly visited.

Yet, because it had been so

cunningly hidden in the beginning, the secret doorway leading off to

one side about two-thirds of the way down the western wall of the

descending corridor, remained sealed and undiscovered until the

nineteenth century.14

What the doorway led to was a narrow well-shaft, about 160 feet in

extent, which rose almost vertically through the bedrock and then

through more than twenty complete courses of the Great Pyramid’s

limestone core blocks, until it joined up with the main internal

corridor system at the base of the Grand Gallery. There is no

evidence to indicate what the purpose of this strange architectural

feature might have been (although several scholars have hazarded

guesses).15

Indeed the only thing that is clear is that it was

engineered at the time of the construction of the pyramid and was

not the result of an intrusion by tunnelling tomb-robbers.16 The

question remains open, however, as to whether tomb-robbers might

have discovered the hidden entrance to the shaft, and made use of it

to siphon off the treasures from the King’s and Queen’s

Chambers.

12 Secrets of the Great Pyramid, p. 58.

13

The Geography of Strabo, (trans. H. L. Jones), Wm. Heinemann,

London, 1982, volume VIII, pp. 91-3.

14 Secrets of the Great

Pyramid, p. 58.

15

In general, it is assumed to have been used as an escape route by

workers sealed within the pyramid above the plugging blocks in the

ascending passage.

16

Because, over a distance of several hundred feet through solid

masonry, it joins two narrow corridors. This could not have been

achieved by accident.

Such a possibility cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, a review of

the

historical record indicates little in its favour.

For example, the upper end of the well-shaft was entered off the

Grand Gallery by the Oxford astronomer John Greaves in 1638. He

managed to descend to a depth of about sixty feet. In 1765 another

Briton, Nathaniel Davison, penetrated to a depth of about 150 feet

but found his way blocked by an impenetrable mass of sand and

stones. Later, in the 1830s, Captain G.B. Caviglia, an Italian

adventurer, reached the same depth and encountered the same

obstacle.

More enterprising than his predecessors, he hired Arab

workers to start excavating the rubble in the hope that there might

be something of interest beneath it. Several days of digging in

claustrophobic conditions followed before the connection with the

descending corridor was discovered.17

Is it likely that such a cramped, blocked-up shaft could have been a

viable conduit for the treasures of Khufu, supposedly the greatest

pharaoh of the magnificent Fourth Dynasty?

Even if it hadn’t been choked with debris and sealed at the lower

end, it could not have been used to bring out more than a tiny

fraction of the treasures of a typical royal tomb. This is because

the well-shaft is only three feet in diameter and incorporates

several tricky vertical sections.

At the very least, therefore, when Ma’mun and his men battered their

way into the King’s Chamber around the year AD 820, one would have

expected some of the bigger and heavier pieces from the original

burial to be still in place—like the statues and shrines that bulked

so large in Tutankhamen’s much later and presumably inferior tomb.18

17 Secrets of the Great Pyramid, pp. 56-8.

18 See Nicholas Reeves,

The Complete Tutankhamun, Thames & Hudson, London, 1990.

But nothing was found inside Khufu’s Pyramid, making this and the

alleged looting of Khafre’s monument the only tomb robberies in the

history of Egypt which achieved a clean sweep, leaving not a single

trace behind—not a torn cloth, not a shard of broken pottery, not an

unwanted figurine, not an overlooked piece of jewellery—just the

bare floors and walls and the gaping mouths of empty sarcophagi.

Not like other tombs

It was now after six in the morning and the rising sun had bathed

the summits of Khufu’s and Khafre’s Pyramids with a fleeting blush

of pastel-pink light. Menkaure’s Pyramid, being some 200 feet lower

than the other two, was still in shadow as Santha and I skirted its

north-western corner and continued our walk into the rolling sand

dunes of the surrounding desert.

I still had the tomb robbery theory on my mind. As far as I could

see the only real ‘evidence’ in favour of it was the absence of

grave goods and mummies that it had been invented to explain in the

first place. All the

other facts, particularly where the Great Pyramid was concerned,

seemed to speak persuasively against any robbery having occurred. It

was not just a matter of the narrowness and unsuitability of the

well-shaft as an escape route for bulky treasures.

The other

remarkable feature of Khufu’s Pyramid was the absence of

inscriptions or decorations anywhere within its immense network of

galleries, corridors, passageways and chambers, and the same was

true of Khafre’s and Menkaure’s Pyramids. In none of these amazing

monuments had a single word been written in praise of the pharaohs

whose bodies they were supposed to house.

This was exceptional. No other proven burial place of any Egyptian

monarch had ever been found undecorated. The fashion throughout

Egyptian history had been for the tombs of the pharaohs to be

extensively decorated, beautifully painted from top to bottom (as in

the Valley of the Kings at Luxor, for example) and densely inscribed

with the ritual spells and invocations required to assist the

deceased on his journey towards eternal life (as in the Fifth

Dynasty pyramids at Saqqara, just twenty miles to the south of

Giza.)19

19

See Valley of the Kings; for Saqqara (Fifth and Sixth Dynasties) see

Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, pp. 163-7.

Why had Khufu, Khafre and

Menkaure done things so differently?

-

Had

they not built their monuments to serve as tombs at all, but for

another and more subtle purpose?

-

Or was it possible, as certain Arab

and esoteric traditions maintained, that the Giza pyramids had been

erected long before the Fourth Dynasty by the architects of some

earlier and more advanced civilization?

Neither hypothesis was popular with Egyptologists for reasons that

were easy to understand. Moreover, while conceding that the Second

and Third Pyramids were completely devoid of internal inscriptions,

lacking even the names of Khafre and Menkaure, the scholars were

able to cite certain hieroglyphic ‘quarry marks’ (graffiti daubed on

stone blocks before they left the quarry) found inside the Great

Pyramid, which did seem to bear the name of Khufu.

A certain smell ...

The discoverer of the quarry marks was Colonel Howard Vyse, during

the destructive excavations he undertook at Giza in 1837. Extending

an existing crawlway, he cut a tunnel into the series of narrow

cavities, called ‘relieving chambers’, which lay directly above the

King’s Chamber.

The quarry marks were found on the walls and

ceilings of the top four of these cavities and said things like

this:

THE CRAFTSMEN-GANG,

HOW POWERFUL IS THE WHITE CROWN OF KHNUM—

KHUFU

KHUFU

KHNUM-KHUFU

YEAR SEVENTEEN20

It was all very convenient. Right at the end of a costly and

otherwise fruitless digging season, just when a major archaeological

discovery was needed to legitimize the expenses he had run up, Vyse

had stumbled upon the find of the decade—the first incontrovertible

proof that Khufu had indeed been the builder of the hitherto

anonymous Great Pyramid.

One would have thought that a discovery of this nature would have

settled conclusively any lingering doubts over the ownership and

purpose of that enigmatic monument. But the doubts remained, largely

because, from the beginning, ‘a certain smell’ hung over Vyse’s

evidence:

1 - It was odd that the marks were the only signs of the name Khufu

ever found anywhere inside the Great Pyramid.21

2 - It was odd that they had been found in such an obscure,

out-of-theway corner of that immense building.

3 - It was odd that they had been found at all in a monument otherwise

devoid of inscriptions of any kind.

4 - And it was extremely odd that they had been found only in the top

four of the five relieving chambers. Inevitably, suspicious minds

began to wonder whether ‘quarry marks’ might also have appeared in

the lowest of these five chambers had that chamber, too, been

discovered by Vyse (rather than by Nathaniel Davison seventy years

earlier).22

5 - Last but not least it was odd that several of the hieroglyphs in

the ‘quarry marks’ had been painted upside down, and that some were

unrecognizable while others had been misspelt or used

ungrammatically.23

Was Vyse a forger?

I know of one plausible case made to suggest he was exactly that,24

and although final proof will probably always be lacking, it seemed

to me incautious of academic Egyptology to have accepted the

authenticity of the quarry marks without question. Besides, there

was alternative hieroglyphic evidence, arguably of purer provenance,

which appeared to indicate that Khufu could not have built the Great

Pyramid.

20 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 211-12; The Great Pyramid: Your

Personal Guide, p. 71.

21 Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 96.

22 Secrets of

the Great Pyramid, p. 35-6.

23 Zecharia Sitchin, The Stairway To

Heaven, Avon Books, New York, 1983, pp. 253-82.

24 Ibid.

Strangely, the same Egyptologists who readily ascribed immense

importance to Vyse’s

quarry marks were quick to downplay the significance of these other,

contradictory, hieroglyphs, which appeared on a rectangular

limestone stela which now stood in the Cairo Museum.25

The Inventory Stela, as it was called, had been discovered at Giza

in the nineteenth century by the French archaeologist Auguste

Mariette. It was something of a bombshell because its text clearly

indicated that both the Great Sphinx and the Great Pyramid (as well

as several other structures on the plateau) were already in

existence long before Khufu came to the throne.

The inscription also

referred to Isis as the ‘Mistress of the Pyramid’, implying that the

monument had been dedicated to the goddess of magic and not to Khufu

at all. Finally, there was a strong suggestion that Khufu’s pyramid

might have been one of the three subsidiary structures alongside the

Great Pyramid’s eastern flank.26

All this looked like damaging evidence against the orthodox

chronology of Ancient Egypt. It also challenged the consensus view

that the Giza pyramids had been built as tombs and only as only.

However, rather than investigating the anachronistic statements in

the Inventory Stela, Egyptologists chose to devalue them. In the

words of the influential American scholar James Henry Breasted,

‘These references would be of the highest importance if the stela

were contemporaneous with Khufu; but the orthographic evidences of

its late date are entirely conclusive ...’27

Breasted meant that the nature of the hieroglyphic writing system

used in he inscription was not consistent with that used in the

Fourth Dynasty but belonged to a more recent epoch: All

Egyptologists concurred with this analysis and the final judgement,

still accepted today, was that the stela had been carved in the

Twenty-First Dynasty, about 1500 years after Khufu’s reign, and was

therefore to be regarded as a work of historical fiction.28

25

James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents

from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, reprinted by

Histories and Mysteries of Man Ltd., London, 1988, pp. 83-5.

26

Ibid., p. 85.

27 Ibid., p. 84.

28 Ibid., and Travellers Key to

Ancient Egypt, p. 139.

Thus, citing orthographic evidence, an entire academic discipline

found reason to ignore the boat-rocking implications of the

Inventory Stela and at no time gave proper consideration to the

possibility that it could have been based upon a genuine Fourth

Dynasty inscription (just as the New English Bible, for example, is

based on a much older original). Exactly the same scholars, however,

had accepted the authenticity of a set of dubious ‘quarry marks’

without demur, turning a blind eye to their orthographic and other

peculiarities.

Why the double standard? Could it have been because the information

contained in the ‘quarry marks’ conformed strictly to orthodox

opinion that the Great Pyramid had been built as a tomb for Khufu?

whereas the

information in the Inventory Stela contradicted that opinion?

Overview

By seven in the morning Santha and I had walked far out into the

desert to the south-west of the Giza pyramids and had made ourselves

comfortable in the lee of a huge dune that offered an unobstructed

panorama over the entire site.

The date, 16 March, was just a few days away from the Spring

Equinox, one of the two occasions in the year when the sun rose

precisely due east of wherever you stood in the world. Ticking out

the days like the pointer of a giant metronome, it had bisected the

horizon this morning at a point a hair’s breadth south of due east

and had already climbed high enough to shrug off the Nile mists

which clung like a shroud to much of the city of Cairo.

Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure ... Cheops, Chephren, Mycerinus. Whether you

called them by their Egyptian or their Greek names, there was no

doubt that the three famous pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty had been

commemorated by the most splendid, the most honourable, the most

beautiful and the most enormous monuments ever seen anywhere in the

world.

Moreover, it was clear that these pharaohs must indeed have

been closely associated with the monuments, not only because of the

folklore passed on by Herodotus (which surely had some basis in

fact) but because inscriptions and references to Khufu, Khafre and

Menkaure had been found in moderate quantities, outside the three

major pyramids, at several different parts of the Giza necropolis.

Such finds had been made consistently in and around the six

subsidiary pyramids, three of which lay to the east of the Great

Pyramid and the other three to the south of the Menkaure Pyramid.

Since much of this external evidence was ambiguous and uncertain, I

found it difficult to understand why the Egyptologists were happy to

go on citing it as confirmation of the ‘tombs and tombs only’

theory.

The problem was that this same evidence was capable of supporting—

as equally valid—a number of different and mutually contradictory

interpretations. To give just one example, the ‘close association’

observed between the three great pyramids and the three Fourth

Dynasty pharaohs could indeed have come about because these pharaohs

had built the pyramids as their tombs. But it could also have come

about if the gigantic monuments of the Giza plateau had been

standing long before the dawn of the historical civilization known

as Dynastic Egypt.

In that case, it was only necessary to assume

that in due course Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure had come along and

built a number of the subsidiary structures around the three older

pyramids—something that they would have had every reason to do

because in this way they could have appropriated the high prestige

of the original anonymous monuments (and would, almost certainly, be

viewed by posterity as their builders).

There were other possibilities too. The point was, however, that the

evidence for exactly who had built which great pyramid, when and for

what purpose was far too thin on the ground to justify the dogmatism

of the orthodox ‘tombs and tombs only’ theory. In all honesty, it

was not clear who built the pyramids. It was not clear in what epoch

they had been built. And it was not at all clear what their function

had been.

For all these reasons they were surrounded by a wonderful,

impenetrable air of mystery and as I gazed down at them out of the

desert they seemed to march towards me across the dunes ...

Back to

Contents

Chapter 36 -

Anomalies

Viewed from our vantage point in the desert south west of the Giza

necropolis, the site plan of the three great pyramids seemed

majestic but bizarre.

Menkaure’s pyramid was closest to us, with Khafre’s and Khufu’s

monuments behind it to the north-east. These two were situated along

a near perfect diagonal—a straight line connecting the south-western

and north-eastern corners of the pyramid of Khafre would, if

extended to the north-east, also pass through the south-western and

north-eastern corners of the Great Pyramid.

This, presumably, was

not an accident. From where we sat, however, it was easy to see that

if the same imaginary straight line was extended to the south-west

it would completely miss the Third Pyramid, the entire body of which

was offset to the east of the principal diagonal.

Egyptologists refused to recognize any anomaly in this. Why should

they? As far as they were concerned there was no site plan at Giza.

The pyramids were tombs and tombs only, built for three different

pharaohs over a period of about seventy-five years.1 It made sense

to assume that each ruler would have sought to express his own

personality and idiosyncrasies through his monument, and this was

probably why Menkaure had ‘stepped out of line’.

The Egyptologists were wrong. Though I was unaware of it that March

morning in 1993, a breakthrough had been made proving beyond doubt

that the necropolis did have an overall site plan, which dictated

the exact positioning of the three pyramids not only in relation to

one another but in relation to the River Nile a few kilometers east

of the Giza plateau.

With eerie fidelity, this immense and ambitious

layout modelled a celestial phenomenon2—which was perhaps why

Egyptologists (who pride themselves on looking exclusively at the

ground beneath their feet) had failed to spot it. On a truly giant

scale, as we see in later chapters, it also reflected the same

obsessive concern with orientations and dimensions demonstrated in

each of the monuments.

1 Atlas of Ancient Egypt, p. 36.

2 The Orion Mystery.

A singular oppression ...

Giza, Egypt, 16 March 1993, 8 a.m.

At a little over 200 feet tall (and with a side length at the base

of 356

feet) the Third Pyramid was less than half the height and well under

half the mass of the Great Pyramid. Nevertheless, it possessed a

stunning and imposing majesty of its own. As we stepped out of the

desert sunlight and into its huge geometrical shadow, I remembered

what the Iraqi writer Abdul Latif had said about it when he had

visited it in the twelfth century:

‘It appears small compared with

the other two; but viewed at a short distance and to the exclusion

of these, it excites in the imagination a singular oppression and

cannot be contemplated without painfully affecting the sight ...’3

The lower sixteen courses of the monument were still cased, as they

had been since the beginning, with facing blocks quarried out of red

granite (‘so extremely hard’, in Abdul Latif s words, ‘that iron

takes a long time, with difficulty, to make an impression on it’).4

Some of the blocks were very large; they were also closely and

cunningly fitted together in a complex interlocking jigsaw-puzzle

pattern strongly reminiscent of the cyclopean masonry at Cuzco,

Machu Picchu and other locations in far-off Peru.

As was normal, the entrance to the Third Pyramid was situated in its

northern face well above the ground. From here, at an angle of 26°

2’, a descending corridor lanced arrow-straight down into the

darkness.5 Oriented exactly north to south, this corridor was

rectangular in section and so cramped that we had to bend almost

double to fit into it. Where it passed through the masonry of the

monument its ceiling and walls consisted of well-fitted granite

blocks. More surprisingly, these continued for some distance below

ground level.

3 Abdul Latif, The Eastern Key, cited in Traveller’s Key to Ancient

Egypt, p. 126.

4 Ibid.

5 Blue Guide: Egypt, A & C Black, London, 1988, p. 433.

At about seventy feet from the entrance, the corridor levelled off

and opened out into a passageway where we could stand up. This led

into a small ante-chamber with carved panelling and grooves cut into

its walls, apparently to take portcullis slabs. Reaching the end of

the chamber, we had to crouch again to enter another corridor. Bent

double, we proceeded south for about forty feet before reaching the

first of the three main burial chambers—if burial chambers they

were.

These sombre, soundless rooms were all hewn out of solid bedrock.

The one that we stood in was rectangular in plan and oriented east

to west. Measuring about 30 feet long x 15 wide x 15 high, it had a

flat ceiling and a complex internal structure with a large,

irregular hole in its western wall leading into a dark, cave-like

space beyond. There was also an opening near the centre of the floor

which gave access to a ramp, sloping westwards, leading down to even

deeper levels. We descended the ramp.

It terminated in a short,

horizontal passage to the right of which, entered through a narrow

doorway, lay a small empty chamber, Six cells, like the sleeping

quarters of medieval monks, had been hewn

out of its walls: four on the eastern side and two to the north.

These were presumed by Egyptologists to have functioned as

‘magazines ... for storing objects which the dead king wished to

have close to his body.’6

Coming out of this chamber, we turned right again, back into the

horizontal passage. At its end lay another empty chamber,7 the

design of which is unique among the pyramids of Egypt. Some twelve

feet long by eight wide, and oriented north to south, its walls and

extensively broken and damaged floor were fashioned out of a

peculiarly dense, chocolate-coloured granite which seemed to absorb

light and sound waves.

Its ceiling consisted of eighteen huge slabs

of the same material, nine on each side, laid in facing gables.

Because they had had been hollowed from below to form a markedly

concave surface, the effect of these great monoliths was of a

perfect barrel vault, much as one might expect to find in the crypt

of a Romanesque cathedral.

Retracing our steps, we left the lower chambers and walked back up

the ramp to the large, flat-roofed, rock-hewn room above. Passing

through the ragged aperture in its western wall, we found ourselves

looking directly at the upper sides of the eighteen slabs which

formed the ceiling of the chamber below. From this perspective their

true form as a pointed gable was immediately apparent. What was less

clear was how they had been brought in here in the first place, let

alone laid so perfectly in position.

Each one must have weighed many

tons, heavy enough to have made them extremely difficult to handle

under any circumstances. And these were no ordinary circumstances.

As though they had set out deliberately to make things more

complicated for themselves (or perhaps because they found such tasks

simple?) the pyramid builders had disdained to provide an adequate

working area between the slabs and the bedrock above them.

By

crawling into the cavity, I was able to establish that the clearance

varied from approximately two feet at the southern end to just a few