|

Chapter 37 -

Made by Some God

I had climbed the Great Pyramid the night before, but as I

approached it in the full glare of midday, I experienced no sense of

triumph. On the contrary, standing at its base on the north side, I

felt fly-sized and puny— an impermanent creature of flesh and blood

confronted with the awe-inspiring splendour of eternity.

I had the

impression that it might have been here for ever, ‘made by some god

and set down bodily in the surrounding sand’, as the Greek historian

Diodorus Siculus commented in the first century BC.1 But which god

had made it, if not the God-King Khufu whose name generations of

Egyptians had associated with it?

For the second time in twelve hours, I began to climb the monument.

Up close in this light, indifferent to human chronologies and

subject only to the slow erosive forces of geological time, it

reared above me like a frowning, terrifying crag. Fortunately, I

only had six courses to clamber over, assisted in places by modern

steps, before reaching Ma’mun’s Hole, which now served as the

pyramid’s principal entrance.

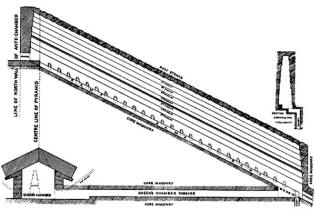

The original entrance, still well-hidden in the ninth century when

Ma’mun began tunnelling, was some ten courses higher, 55 feet above

ground level and 24 feet east of the main north-south axis.

Protected by giant limestone gables, it contained the mouth of the

descending corridor, which led downwards at an angle of 26° 31’ 23”.

Strangely, although itself measuring only some 3 feet 5 inches x 3

feet 11 inches, this corridor was sandwiched between roofing blocks

8 feet 6 inches thick and 12 feet wide and a flooring slab (known as

the ‘Basement Sheet’) 2 feet 6 inches thick and 33 feet wide.2

1 Diodorus Siculus, Harvard University Press, 1989, p. 217.

2 The

Pyramids of Egypt, p. 88; The Great Pyramid: Your Personal Guide,

pp. 30-1.

Hidden structural features like these abounded in the Great Pyramid,

manifesting both incredible complexity and apparent pointlessness.

Nobody knew how blocks of this size had been successfully installed,

neither did anybody know how they had been set so carefully in

alignment with other blocks, or at such precise angles (because, as

the reader may have realized, the 26° slope of the descending

corridor was part of a deliberate and regular pattern). Nobody knew

either why these things had been done.

The Beacon

Entering the pyramid through Ma’mun’s Hole did not feel right. It

was like

entering a cave or grotto cut into the side of a mountain; it lacked

the sense of deliberate and geometrical purposefulness that would

have been conveyed by the original descending corridor. Worse still,

the dark and inauspicious horizontal tunnel leading inwards looked

like an ugly, deformed thing and still bore the marks of violence

where the Arab workmen had alternately heated and chilled the stones

with fierce fires and cold vinegar before attacking them with

hammers and chisels, battering rams and borers.

On the one hand, such vandalism seemed gross and irresponsible. On

the other, a startling possibility had to be considered: was there

not a sense in which the pyramid seemed to have been designed to

invite human beings of intelligence and curiosity to penetrate its

mysteries?

After all, if you were a pharaoh who wanted to ensure

that his deceased body remained inviolate for eternity, would it

make better sense,

(a) to advertise to your own and all subsequent

generations the whereabouts of your burial place, or

(b) to choose

some secret and unknown location, of which you would never speak and

where you might never be found?

The answer was obvious: you would go for secrecy and seclusion, as

the vast majority of the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt had done.3

3 In the isolated Valley of the Kings in Luxor in upper Egypt, for

example.

-

Why, then, if it was indeed a royal tomb, was the Great Pyramid so

conspicuous?

-

Why did it occupy a ground area of more than thirteen

acres?

-

Why was it almost 500 feet high?

-

Why, in other words, if its

purpose was to conceal and protect the body of Khufu, had it been

designed so that it could not fail to attract the attention—in all

epochs and under all imaginable circumstances—of treasure-crazed

adventurers and of prying and imaginative intellectuals?

It was simply not credible that the brilliant architects,

stonemasons, surveyors and engineers who had created the Great

Pyramid could have been ignorant of basic human psychology. The vast

ambition and the transcendent beauty, power and artistry of their

handiwork spoke of refined skills, deep insight, and a complete

understanding of the symbols and primordial patterns by which the

minds of men could be manipulated.

Logic therefore suggested that

the pyramid builders must also have understood exactly what kind of

beacon they were piling up (with such incredible precision) on this

windswept plateau, on the west bank of the Nile, in those high and

far away times.

They must, in short, have wanted this remarkable structure to exert

a perennial fascination: to be violated by intruders, to be measured

with increasing degrees of exactitude, and to haunt the collective

imagination of mankind like a persistent ghost summoning intimations

of a profound and long-forgotten secret.

Mind games of the pyramid builders

The point where Ma’mun’s Hole intersected with the 26° descending

corridor was closed off by a modern steel door. Beyond it, to the

north, that corridor sloped up until it reached the gables of the

monument’s original entrance. To the south, as we have seen, the

corridor sloped down for almost another 350 feet into the bedrock,

before opening out into a huge subterranean chamber 600 feet beneath

the apex of the pyramid. The accuracy of this corridor was

astonishing. From top to bottom the average deviation from straight

amounted to less than 1/4inch in the sides and 3/10-inch on the

roof.4

Passing the steel door, I continued through Ma’mun’s tunnel,

breathing in its ancient air and adjusting my eyes to the gloom of

the low-wattage bulbs that lit it. Then ducking my head I began to

climb through the steep and narrow section hacked upwards by the

Arab diggers in their feverish thrust to by-pass the series of

granite plugs blocking the lower part of the ascending corridor.

At

the top of the tunnel two of the original plugs could be seen, still

in situ but partially exposed by quarrying. Egyptologists assumed

that they had been slid into their present position from above5—all

the way down the lag-foot length of the ascending corridor from the

foot of the Grand Gallery.6

Builders and engineers, however, whose

trend of thought was perhaps more practical, had pointed out that it

was physically impossible for the plugs to have been installed in

this way. Because of the leaf-thin clearance that separated them

from the walls, floor and ceiling of the corridor, friction would

have foiled any ‘sliding’ operation in a matter of inches, let alone

100 feet.7

4 The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 19.

5 Discussed in Secrets

of the Great Pyramid, p. 230ff.

6 Dimension from The Traveller’s Key

to Ancient Egypt, p. 114.

7 Secrets of the Great Pyramid, p. 230ff.

The puzzling implication was therefore that the ascending corridor

must have been plugged while the pyramid was still being built. But

why would anyone have wished to block the main entrance to the

monument at such an early stage in its construction (even while

continuing to enlarge and elaborate its inner chambers)?

Moreover,

if the objective had been to deny intruders admission, wouldn’t it

have been much easier and more efficient to have plugged the

descending corridor from its entrance in the north face to a point

below its junction with the ascending corridor? That would have been

the most logical way to seal the pyramid and would have made plugs

unnecessary in the ascending corridor.

There was only one certainty: since the beginning of history, the

single known effect of the granite plugs had not been to prevent an

intruder from gaining access; instead, like Bluebeard’s locked door,

the barrier had magnetized Ma’mun’s attention and inflamed his

curiosity so that he had felt compelled to tunnel his way past them,

convinced that

something of inestimable value must lie beyond them.

Might this not have been what the pyramid builders had intended the

first intruder who reached this far to feel? It would be premature

to rule out such a strange and unsettling possibility. At any rate,

thanks to Ma’mun (and to the predictable constants of human nature)

I was now able to insert myself into the unblocked upper section of

the original ascending corridor. A smoothly cut aperture measuring 3

feet 5 inches wide x 3 feet 11 inches high (exactly the same

dimensions as the descending corridor), it sloped up into the

darkness at an angle of 26° 2’ 30” 8 (as against 26° 31’ 23” in the

descending corridor).9

What was this meticulous interest in the angle of 26°, and was it a

coincidence that it amounted to half of the angle of inclination of

the pyramid’s sides—52°.10

The reader may recall the significance of this angle. It was a key

ingredient of the sophisticated and advanced formula by which the

design of the Great Pyramid had been made to correspond precisely to

the dynamics of spherical geometry. Thus the original height of the

monument (481.3949 feet), and the perimeter of its base (3023.16

feet), stood in the same ratio to each other as did the radius of a

sphere to its circumference.

This ratio was 2pi (2 x 3.14) and to

express it the builders had been obliged to specify the tricky and

idiosyncratic angle of 52° for the pyramid’s sides (since any

greater or lesser slope would have meant a different

height-to-perimeter ratio).

In Chapter Twenty-three we saw that the so-called Pyramid of the Sun

at Teotihuacan in Mexico also expressed a knowledge and deliberate

use of the transcendental number pi; in its case the height (233.5

feet) stood in a relationship of 4pi to the perimeter of its base

(2932.76 feet).11

The crux, therefore, was that the most remarkable monument of

Ancient Egypt and the most remarkable monument of Ancient Mexico

both incorporated pi relationships long before and far away from the

official ‘discovery’ of this transcendental number by the Greeks.12

Moreover, the evidence invited the conclusion that something was

being signalled by the use of pi—almost certainly the same thing in

both cases.

8 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 91.

9 Ibid., p. 88.

10 Or 51° 50’ 35” to be exact, Ibid., page 87; Traveller’s Key to

Ancient Egypt, p. 112.

11 See Chapter Twenty-three.

12 Ibid.

Not for the first time, and not for the last, I was overwhelmed by a

sense of contact with an ancient intelligence, not necessarily

Egyptian or Mexican, which had found a way to reach out across the

ages and draw people towards it like a beacon. Some might look for

treasure; others, captivated by the deceptively simple manner in

which the builders had used pi to demonstrate their mastery of the

secrets of transcendental numbers, might be inspired to search for

further mathematical

epiphanies.

Bent almost double, my back brushing against the polished limestone

ceiling, it was with such thoughts in my mind that I began to

scramble up the 26° slope of the ascending corridor, which seemed to

penetrate the vast bulk of the six million ton building like a

trigonometrical device.

After I had banged my head on its ceiling a

couple of times, however, I began to wonder why the ingenious people

who’d designed it hadn’t made it two or three feet higher. If they

could erect a monument like this in the first place (which they

obviously could) and equip it with corridors, surely it would not

have been beyond their capabilities to make those corridors roomy

enough to stand up in?

Once again I was tempted to conclude that it

was the result of a deliberate decision by the pyramid builders:

they had made the ascending corridor this way because they had

wanted it this way (rather than because such a design had been

forced upon them.)

Was there motive in the apparent madness of these archaic mind

games?

Unknown dark distance

At the top of the ascending corridor I emerged into yet another

inexplicable feature of the pyramid, ‘the most celebrated

architectural work to have survived from the Old Kingdom’13—the

Grand Gallery. Soaring upwards at the continuing majestic angle of

26°, and almost entirely vanishing into the airy gloom above, its

spacious corbelled vault made a stunning impression.

It was not my intention to climb the Grand Gallery yet. Branching

off due south at its base was a long horizontal passageway, 3 feet 9

inches high and 127 feet in length, that led to the Queen’s

Chamber.14 I wanted to revisit this room, which I had admired for

its stark beauty since becoming acquainted with the Great Pyramid

several years previously. Today, however, to my considerable

irritation, the passageway was barred within a few feet of its

entrance.

13 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 93.

14 Dimensions from Traveller’s Key to

Ancient Egypt, p. 121, and The Pyramids of Egypt,

p. 93.

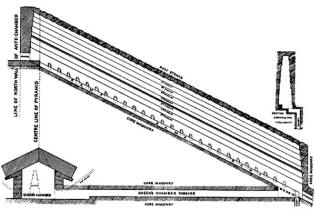

The Grand Gallery and the King’s and Queen’s Chambers with their

northern and southern shafts.

The reason, though I was unaware of it at the time, was that a

German robotics engineer named

Rudolf Gantenbrink

was at work

within, slowly and painstakingly manoeuvring a $250,000 robot up the

narrow southern shaft of the Queen’s Chamber. Hired by the Egyptian

Antiquities Organization to improve the ventilation of the Great

Pyramid, he had already used his high-tech equipment to clear debris

from the King’s Chamber’s narrow ‘southern shaft’ (believed by

Egyptologists to have been designed as a ventilation shaft in the

first place) and had installed an electric fan at its mouth.

At the

beginning of March 1993 he transferred his attentions to the Queen’s

Chamber, deploying Upuaut, a miniaturized remote-controlled robot

camera to explore its southern shaft.

On 22 March, some 200 feet

along the steeply sloping shaft (which rose at an angle of 39.5° and

was only about 8 inches high x 9 inches wide),15 the floor and walls

suddenly became very smooth as Upuaut crawled into a section made of

fine Tura limestone, the type normally used for lining sacred areas

such as chapels or tombs.

That, in itself, was intriguing enough,

but at the end of this corridor, apparently leading to a sealed

chamber deep within the pyramid’s masonry, was a solid limestone

door complete with metal fittings ...

15 The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 24.

It had long been known that neither this southern shaft nor its

counterpart in the Chamber’s northern wall had any exit on the

outside of the Great Pyramid. In addition, and equally inexplicably,

neither had originally been fully cut through. For some reason the

builders had left the last five inches of stone intact in the last

block over the mouth of each of the shafts, thus rendering them

invisible and inaccessible to any

casual intruder.

-

Why?

-

To make sure they would never be found?

-

Or to make sure that

they would be found, some day, under the right circumstances?

After all, there had from the beginning been two conspicuous shafts

in the King’s Chamber, penetrating the north and south walls. It

should not have been beyond the mental powers of the pyramid

builders to predict that sooner or later some inquiring person would

be tempted to look for shafts in the Queen’s Chamber as well. In the

event nobody did look for more than a thousand years after Caliph

Ma’mun had opened the monument to the world in AD 820.

Then in 1872

an English engineer named Waynman Dixon, a Freemason who ‘had been

led to suspect the existence of the shafts by their presence in the

King’s Chamber above’,16 went tapping around the Queen’s Chamber’s

walls and located them.

He opened the southern shaft first, setting

his,

‘carpenter and man-of-allwork, Bill Grundy, to jump a hole with

a hammer and steel chisel at that place. So to work the faithful

fellow went, and with a will which soon began to make a way into the

soft stone [limestone] at this point, when lo! after a comparatively

very few strokes, flop went the chisel right through into something

or other.’17

The ‘something or other’ Bill Grundy’s chisel had reached turned out

to be,

‘a rectangular, horizontal, tubular channel, about 9 inches by

8 inches in transverse breadth and height, going back 7 feet into

the wall, and then rising at an angle into an unknown, dark distance

...’18

It was up that angle, and into that ‘unknown dark distance’, 121

years later, that Rudolf Gantenbrink sent his robot—the technology

of our species having finally caught up with our powerful instincts

to pry.

Those instincts were clearly no weaker in 1872 than in 1993;

among the many interesting things the remote-controlled camera

succeeded in filming in the Queen’s Chamber shafts was the far end

of a long, sectioned metal rod of nineteenth century design which Waynman Dixon and the faithful Bill Grundy had secretly stuffed up

the intriguing channel.19

Predictably, they had assumed that if the

pyramid builders had gone to the trouble of constructing and then

concealing the shafts, then they must have hidden something worth

looking for inside them.

16 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 92.

17 The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets

and Mysteries Revealed, p. 428.

18 Ibid.

19

Presentation at the British Museum, 22 November 1993, by Rudolf

Gantenbrink, of footage shot in the shafts by the robot camera

Upuaut.

The notion that there might have been an intention from the outset

to stimulate such investigations would seem quite implausible if the

final upshot of the discovery and exploration of the shafts had been

a dead-end. Instead, as we have seen, a door was found—a sliding,

portcullis door with curious metal fittings and an enticing gap at

its base beneath which the laser-spot projected by Gantenbrink’s

robot was seen to

disappear entirely ...

Once again there seemed to be a clear invitation to proceed further,

the latest in a long line of invitations which had encouraged Caliph Ma’mun and his diggers to break into the central passageways and

chambers of the monument, which had waited for Waynman Dixon to test

the hypothesis that the walls of the Queen’s Chamber might contain

concealed shafts, and which had then waited again until arousing the

curiosity of Rudolf Gantenbrink, whose high-tech robot revealed the

existence of the hidden door and brought within reach whatever

secrets— or disappointments, or further invitations—might lie behind

it.

The Queen’s Chamber

We shall hear more of Rudolf Gantenbrink and

Upuaut in later

chapters. 16 March 1993, however, knowing nothing of this, I was

frustrated to find the Queen’s Chamber closed, and glared

resentfully through the metal grille that barred its entrance

corridor.

I remembered that the height of that corridor, 3 feet 9 inches, was

not constant. Approximately 110 feet due south from where I stood,

and only about 15 feet from the entrance to the Chamber, a sudden

downward step in the floor increased the standing-room to 5 feet 8

inches.20 Nobody had come up with a convincing explanation for this

peculiar feature.

The Queen’s Chamber itself—apparently empty since the day it was

built—measured 17 feet 2 inches from north to south and 18 feet 10

inches from east to west. It was equipped with an elegant gabled

ceiling, 20 feet 5 inches in height, which lay exactly along the

east-west axis of the pyramid.21 Its floor, however, was the

opposite of elegant and looked unfinished. There was a constant

salty emanation through its pale, rough-hewn limestone walls, giving

rise to much fruitless speculation.

In the north and south walls, still bearing the incised legend

OPENED 1872, were the rectangular apertures discovered by Waynman

Dixon which led into the dark distance of the mysterious shafts. The

western wall was quite bare. Offset a little over two feet to the

south of its centre line, the eastern wall was dominated by a niche

in the form of a corbel vault 15 feet 4 inches high and 5 feet 2

inches wide at the base. Originally 3 feet 5 inches deep, a further

cavity had been cut in the back of this niche in medieval times by

Arab treasure-seekers looking for hidden chambers.22 They had found

nothing.

Egyptologists had also been unable to come to any persuasive

conclusions about the original function of the niche, or, for that

matter, of the Queen’s Chamber as a whole.

20 The Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 92-3.

21 Ibid., p. 92; The Pyramids

and Temples of Gizeh, p. 23.

22 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 92.

All was confusion. All was paradox. All was mystery.

Instrument

The Grand Gallery had its mysteries too. Indeed it was among the

most mysterious of all the internal features of the Great Pyramid.

Measuring 6 feet 9 inches wide at the floor, its walls rose

vertically to a height of 7 feet 6 inches; above that level

seven

further courses of masonry (each one projecting inwards some 3

inches beyond the course immediately below it) carried the vault to

its full height of 28 feet and its culminating width of 3 feet 5

inches.23 seven

further courses of masonry (each one projecting inwards some 3

inches beyond the course immediately below it) carried the vault to

its full height of 28 feet and its culminating width of 3 feet 5

inches.23

Remember that structurally the Gallery was required to support, for

ever, the multi-million ton weight of the upper three-quarters of

the largest and heaviest stone monument ever built on planet earth.

Was it not quite remarkable that a group of supposed ‘technological

primitives’ had not only envisaged and designed such a feature but

had completed it successfully, more than 4500 years before our time?

Even if they had made the Gallery only 20 feet long, and had sought

to erect it on a level plane, the task would have been difficult

enough— indeed extraordinarily difficult. But they had opted to

erect this astonishing corbel vault at a slope of 26°, and to extend

its length to a staggering 153 feet.24 Moreover, they had made it

with perfectly dressed limestone megaliths throughout—huge, smoothly

polished blocks carved into sloping parallelograms and laid together

so closely and with such rigorous precision that the joints were

almost invisible to the naked eye.

The pyramid builders had also included some interesting symmetries

in their work. For example, the culminating width of the Gallery at

its apex was 3 feet 5 inches while its width at the floor was 6 feet

9 inches. At the exact centre of the floor, running the entire

length of the Gallery—and sandwiched between flat-topped masonry

ramps each 1 foot 8 inches wide—there was a sunken channel 2 feet

deep and 3 feet 5 inches wide.

What could have been the purpose of

this slot? And why had it been necessary for it to mirror so

precisely the width and form of the ceiling, which also looked like

a ‘slot’ sandwiched between the two upper courses of masonry?

I knew that I was not the first person to have stood at the foot of

the Grand Gallery and to have been overtaken by the disorienting

sense of being ‘in the inside of some enormous instrument of some

sort.’25 Who was to say that such intuitions were completely wrong?

Or, for that matter, that they were right? No record as to function

remained, other than in mystical and symbolic references in certain

ancient Egyptian

23 Ibid., p. 93; Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p. 115.

24 The

Pyramids of Egypt, p. 93.

25 Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p.

115.

liturgical texts. These appeared to indicate that the pyramids had

been seen as devices designed to turn dead men into immortal beings:

to ‘throw open the doors of the firmament and make a road’, so that

the deceased pharaoh might ‘ascend into the company of the gods’.26

I had no difficulty accepting that such a belief system might have

been at work here, and obviously it could have provided a motive for

the whole enterprise. Nevertheless, I was still puzzled why more

than six million tons of physical apparatus, intricately interlaced

with channels and tubes, corridors and chambers, had been deemed

necessary to achieve a mystical, spiritual and symbolic objective.

Being inside the Grand Gallery did feel like being inside an

enormous instrument. It had an undeniable aesthetic impact upon me

(admittedly a heavy and domineering one), but it was also completely

devoid of decorative features and of anything (figures of deities,

reliefs of liturgical texts, and so on) which might be suggestive of

worship or religion.

The primary impression it conveyed was one of

strict functionalism and purposefulness—as though it had been built

to do a job. At the same time I was aware of its focused solemnity

of style and gravity of manner, which seemed to demand nothing less

than serious and complete attention.

By now I had climbed steadily through about half the length of the

Gallery. Ahead of me, and behind, shadows and light played tricks

amid the looming stone walls. Pausing, I turned my head, looking

upwards through the gloom towards the vaulted ceiling which

supported the crushing weight of the Great Pyramid of Egypt.

It suddenly hit me how dauntingly and disturbingly old it was, and

how completely my life at this moment depended on the skills of the

ancient builders. The hefty blocks that spanned the distant ceiling

were examples of those skills—every one of them laid at a slightly

steeper gradient than that of the Gallery. As the great

archaeologist and surveyor Flinders Petrie had observed, this had

been done

in order that the lower edge of each stone should hitch like a pawl

into a ratchet cut into the top of the walls; hence no stone can

press on the one below it, so as to cause a cumulative pressure all

down the roof; and each stone is separately upheld by the side walls

which it lies across.27

26 The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, p. 281, Utt. 667A.

27 The

Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 25.

And this was the work of a people whose civilization had only recently emerged from neolithic hunter-gathering?

I began to walk up the Gallery again, using the 2-foot-deep central

flooring slot. A modern wooden covering fitted with helpful slats

and side railings made the ascent relatively easy. In antiquity,

however, the floor had been smoothly polished limestone, which, at a

gradient of 26°, must have been almost impossible to climb.

How had it been done? Had it been done at all?

Looming ahead at the end of the Grand Gallery was the dark opening

to the King’s Chamber beckoning each and every inquiring pilgrim

into the heart of the enigma.

Back to

Contents

Chapter 38 -

Interactive Three-Dimensional Game

Reaching the top of the Grand Gallery, I clambered over a chunky

granite step about three feet high. I remembered that it lay, like

the roof of the Queen’s Chamber, exactly along the east-west axis of

the Great Pyramid, And therefore marked the point of transition

between the northern and southern halves of the monument.1 Somewhat

like an altar in appearance, the step also provided a solid

horizontal platform immediately in front of the low square tunnel

that served as the entrance to the King’s Chamber.

1 The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 25.

Pausing for a moment, I looked back down the Gallery, taking in once

again its lack of decoration, its lack of religious iconography, and

its absolute lack of any of the recognizable symbolism normally

associated with the archaic belief system of the Ancient Egyptians.

All that registered upon the eye, along the entire 153-foot length

of this magnificent geometrical cavity, was its disinterested

regularity and its stark machinelike simplicity.

Looking up, I could just make out the opening of a dark aperture,

chiselled into the top of the eastern wall above my head. Nobody

knew when or by whom this foreboding hole had been cut, or how deep

it had originally penetrated. It led to the first of the five

relieving chambers above the King’s Chamber and had been extended in

1837 when Howard Vyse had used it to break through to the remaining

four.

Looking down again, I could just make out the point at the

bottom of the Gallery’s western wall where the near-vertical

well-shaft began its precipitous 160 foot descent through the core

of the pyramid to join the descending corridor far below

ground-level.

Why would such a complicated apparatus of pipes and passageways have

been required? At first sight it didn’t make sense. But then nothing

about the Great Pyramid did make much sense, unless you were

prepared to devote a great deal of attention to it. In unpredictable

ways, when you did that, it would from time to time reward you.

If you were sufficiently numerate, for example, as we have seen, it

would respond to your basic inquiries into its height and base

perimeter by ‘printing out’ the value of pi. And if you were

prepared to investigate further, as we shall see, it would download

other useful mathematical tidbits, each a little more complex and

abstruse that its predecessor.

There was a programmed feel about this whole process, as though it

had been carefully prearranged. Not for the first time, I found

myself willing to consider the possibility that the pyramid might

have been

designed as a gigantic challenge or learning machine—or, better

still, as an interactive three-dimensional puzzle set down in the

desert for humanity to solve.

Antechamber

Just over 3 feet 6 inches high, the entry passage to the lung’s

Chamber required all humans of normal stature to stoop. About four

feet farther on, however, I reached the ‘Antechamber’, where the

roof level rose suddenly to 12 feet above the floor.

The east and

west walls of the Antechamber were composed of red granite, into

which were cut four opposing pairs of wide parallel slots, assumed

by Egyptologists to have held thick portcullis slabs.2 Three of

these pairs of slots extended all the way to the floor, and were

empty.

2 The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 94.

The fourth (the northernmost) had been cut down only as far

as the roof level of the entry passage (that is, 3 feet 6 inches

above floor level) and still contained a hulking sheet of granite,

perhaps nine inches thick and six feet high. There was a horizontal

space of only 21 inches between this suspended stone portcullis and

the northern end of the entry passage from which I had just emerged.

There was also a gap of a little over 4 feet deep between the top of

the portcullis and the ceiling. Whatever function it was designed to

serve it was hard to agree with the Egyptologists that this peculiar

structure could have been intended to deny access to tomb robbers.

The antechamber.

Genuinely puzzled, I ducked under it and then stood up again in the

southern portion of the Antechamber, which was some 10 feet long and

maintained the same roof height of 12 feet. Though much worn, the

grooves for the three further ‘portcullis’ slabs were still visible

in the eastern and western walls. There was no sign of the slabs

themselves and, indeed, it was difficult to see how such cumbersome

pieces of stone could have been installed in so severely constricted

a working space.

I remembered that Flinders Petrie, who had systematically surveyed

the entire Giza necropolis in the late nineteenth century, had

commented on a similar puzzle in the Second Pyramid:

‘The granite

portcullis in the lower passage shows great skill in moving masses,

as it would need 40 or 60 men to lift it; yet it has been moved, and

raised into place, in a narrow passage, where only a few men could

possibly reach it.’3

Exactly the same observations applied to the

portcullis slabs of the Great Pyramid. If they were portcullis

slabs—gateways capable of being raised and lowered.

3 The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 36.

The problem was that the physics of raising and lowering them

required they be shorter than the full height of the Antechamber, so

that they could be drawn into the roof space to allow the entry and

exit of legitimate individuals prior to the closure of the tomb.

This meant, of course, that when the bottom edges of the slabs were

lowered to the floor to block the Antechamber at that level, an

equal and opposite space would have opened up between the top edges

of the slabs and the ceiling, through which any enterprising

tomb-robber would certainly have been able to climb.

The Antechamber clearly qualified as another of the pyramid’s many

thought-provoking paradoxes, in which complexity of structure was

combined with apparent pointlessness of function.

An exit tunnel, the same height and width as the entrance tunnel and

lined with solid red granite, led off from the Antechamber’s

southern wall (also made of granite but incorporating a 12-inch

thick limestone layer at its very top). After about a further 9 feet

the tunnel debouched into the King’s Chamber, a massive sombre red

room made entirely of granite, which radiated an atmosphere of

prodigious energy and power.

Stone enigmas

I moved into the centre of the King’s Chamber, the lung axis of

which was perfectly oriented east to west while the short axis was

equally perfectly oriented north to south. The room was exactly 19

feet 1 inch in height and formed a precise two-by-one rectangle

measuring 34 feet 4 inches long by 17 feet 2 inches wide.

With a

floor consisting of 15 massive granite paving stones, and walls

composed of 100 gigantic granite blocks, each weighing 70 tons or

more and laid in five courses, and with a ceiling spanned by nine

further granite blocks each weighing approximately 50 tons,4 the

effect was of intense and overwhelming

compression.

At the Chamber’s western end was the object which, if the

Egyptologists were to be believed, the entire Great Pyramid, had

been built to house. That object, carved out of one piece of dark

chocolatecoloured granite containing peculiarly hard granules of

feldspar, quartz and mica, was the lidless coffer presumed to have

been the sarcophagus of Khufu.5

Its interior measurements were 6

feet 6.6 inches in length, 2 feet 10.42 inches in depth, and 2 feet

2.81 inches in width. Its exterior measurements were 7 feet 5.62

inches in length, 3 feet 5.31 inches in depth, and 3 feet 2.5 inches

in width6 an inch too wide, incidentally, for it to have been

carried up through the lower (and now plugged) entrance to the

ascending corridor.7

4 The Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 94-5; The Great Pyramid: Your Personal

Guide, p. 64.

5 The Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 94-5.

6 The Pyramids and

Temples of Gizeh, p. 30.

7 Ibid., p. 95.

Some routine mathematical games were built into the dimensions of

the sarcophagus. For example, it had an internal volume of 1166.4

liters and an external volume of exactly twice that, 2332.8 liters.8

Such a precise coincidence could not have been arrived at

accidentally: the walls of the coffer had been cut to machine-age

tolerances by craftsmen of enormous

skill and experience. It seemed, moreover, as Flinders Petrie

admitted with some puzzlement after completing his painstaking

survey of the Great Pyramid, that these craftsmen had access to

tools ‘such as we ourselves have only now reinvented ...’9

Petrie examined the sarcophagus particularly closely and reported

that it must have been cut out of its surrounding granite block with

straight saws ‘8 feet or more in length’. Since the granite was

extremely hard, he could only assume that these saws must have had

bronze blades (the hardest metal then supposedly available) inset

with ‘cutting points’ made of even harder jewels:

‘The character of

the work would certainly seem to point to diamond as being the

cutting jewel; and only the considerations of its rarity in general,

and its absence from Egypt, interfere with this conclusion ...’10

An even bigger mystery surrounded the hollowing out of the

sarcophagus, obviously a far more difficult enterprise than

separating it from a block of bedrock. Here Petrie concluded that

the Egyptians must have:

adapted their sawing principle into a circular instead of a

rectilinear form, curving the blade round into a tube, which drilled

out a circular groove by its rotation; thus by breaking away the

cores left in such grooves, they were able to hollow out large holes

with a minimum of labour. These tubular drills varied from 1/4 inch

to 5 inches diameter, and from 1/30 to 1/5 inch thick ...11

Of course, as Petrie admitted, no actual jewelled drills or saws had

ever been found by Egyptologists.12 The visible evidence of the

kinds of drilling and sawing that had been done, however, compelled

him to infer that such instruments must have existed.

He became

especially interested in this and extended his study to include not

only the King’s Chamber sarcophagus but many other granite artifacts

and granite ‘drill cores’ which he collected at Giza. The deeper his

research, however, the more puzzling the stone-cutting technology of

the Ancient Egyptians became:

The amount of pressure, shown by the rapidity with which the drills

and saws pierced through the hard stones, is very surprising;

probably a load of at least a ton or two was placed on the 4-inch

drills cutting in granite. On the granite core No 7 the spiral of

the cut sinks 1 inch in the circumference of 6 inches, a rate of

ploughing out which is astonishing ... These rapid spiral grooves

cannot be ascribed to anything but the descent of the drill into the

granite under enormous pressure ...13

8

Livio Catullo Stecchini in Secrets of the Great Pyramid, p. 322.

Stecchini gives slightly more accurate measures than those of Petrie

(quoted) for the internal and external dimensions of the pyramid.

9 Secrets of the Great Pyramid, p. 103.

10 The Pyramids and Temples

of Gizeh, p. 74.

11 Ibid., p. 76.

12 Ibid., p. 78.

13 Ibid.

Wasn’t it peculiar that at the supposed dawn of human civilization,

more than 4500 years ago, the Ancient Egyptians had acquired what

sounded

like industrial-age drills packing a ton or more of punch and

capable of slicing through hard stones like hot knives through

butter?

Petrie could come up with no explanation for this conundrum. Nor was

he able to explain the kind of instrument used to cut hieroglyphs

into a number of diorite bowls with Fourth Dynasty inscriptions

which he found at Giza:

‘The hieroglyphs are incised with a very

free-cutting point; they are not scraped or ground out, but are

ploughed through the diorite, with rough edges to the line ...’14

This bothered the logical Petrie because he knew that diorite was

one of the hardest stones on earth, far harder even than iron.15 Yet

here it was in Ancient Egypt being cut with incredible power and

precision by some as yet unidentified graving tool:

As the lines are only 1/150 inch wide it is evident that the cutting

point must have been much harder than quartz; and tough enough not

to splinter when so fine an edge was being employed, probably only

1/200 inch wide. Parallel lines are graved only 1/30 inch apart from

centre to centre.16

In other words, he was envisaging an instrument with a needle-sharp

point of exceptional, unprecedented hardness capable of penetrating

and furrowing diorite with ease, and capable also of withstanding

the enormous pressures required throughout the operation. What sort

of instrument was that? By what means would the pressure have been

applied? How could sufficient accuracy have been maintained to scour

parallel lines at intervals of just 1/30-inch?

At least it was possible to conjure a mental picture of the circular

drills with jewelled teeth which Petrie supposed must have been used

to hollow out the lung’s Chamber sarcophagus. I found, however, that

it was not so easy to do the same for the unknown instrument capable

of incising hieroglyphs into diorite at 2500 BC, at any rate not

without assuming the existence of a far higher level of technology

than Egyptologists were prepared to consider.

Nor was it just a few hieroglyphs or a few diorite bowls. During my

travels in Egypt I had examined many stone vessels—dating back in

some cases to pre-dynastic times—that had been mysteriously hollowed

out of a range of materials such as diorite, basalt, quartz crystal

and metamorphic schist.17

For example, more than 30,000 such vessels had been found in the

chambers beneath the Third Dynasty Step Pyramid of Zoser at

Saqqara.18 That meant that they were at least as old as Zoser

himself (i.e. around 2650 BC19). Theoretically, they could have been

even older than that,

because identical vessels had been found in pre-dynastic strata

dated to 4000 BC and earlier,20 and because the practice of handing

down treasured heirlooms from generation to generation had been

deeply ingrained in Egypt since time immemorial.

Whether they were made in 2500 BC or in 4000 BC or even earlier, the

stone vessels from the Step Pyramid were remarkable for their

workmanship, which once again seemed to have been accomplished by

some as yet unimagined (and, indeed, almost unimaginable) tool.

Why unimaginable? Because many of the vessels were tall vases with

long, thin, elegant necks and widely flared interiors, often

incorporating fully hollowed-out shoulders. No instrument yet

invented was capable of carving vases into shapes like these,

because such an instrument would have had to have been narrow enough

to have passed through the necks and strong enough (and of the right

shape) to have scoured out the shoulders and the rounded interiors.

And how could sufficient upward and outward pressure have been

generated and applied within the vases to achieve these effects?

The tall vases were by no means the only enigmatic vessels unearthed

from the Pyramid of Zoser, and from a number of other archaic sites.

There were monolithic urns with delicate ornamental handles left

attached to their exteriors by the carvers. There were bowls, again

with extremely narrow necks like the vases, and with widely flared,

pot-bellied interiors. There were also open bowls, and almost

microscopic vials, and occasional strange wheel-shaped objects cut

out of metamorphic schist with inwardly curled edges planed down so

fine that they were almost translucent.21

14 Ibid., pp. 74-5.

15 The Pyramids: An Enigma Solved, p. 8.

16 The Pyramids and Temples

of Gizeh, p. 75.

17 The Pyramids: An Enigma Solved, p. 118.

18

Egypt: Land of the Pharaohs, Time-Life Books, 1992, p. 51.

19 Atlas

of Ancient Egypt, p. 36.

20

For example, see Cyril Aldred, Egypt to the End of the Old Kingdom,

Thames & Hudson, London, 1988, p. 25.

21 Ibid., p. 57. The relevant artefacts are in the Cairo Museum.

In all cases what was

really perplexing was the precision with which the interiors and

exteriors of these vessels had been made to correspond—curve

matching curve—over absolutely smooth, polished surfaces with no

tool marks visible.

There was no technology known to have been available to the Ancient

Egyptians capable of achieving such results. Nor, for that matter,

would any stone-carver today be able to match them, even if he were

working with the best tungsten-carbide tools. The implication,

therefore, is that an unknown or secret technology had been put to

use in Ancient Egypt.

Ceremony of the sarcophagus

Standing in the King’s Chamber, facing west—the direction of death

amongst both the Ancient Egyptians and the Maya—I rested my hands

lightly on the gnarled granite edge of the sarcophagus which

Egyptologists insist had been built to house the body of Khufu. I

gazed

into its murky depths where the dim electric lighting of the chamber

seemed hardly to penetrate and saw specks of dust swirling in a

golden cloud.

It was just a trick of light and shadow, of course, but the King’s

Chamber was full of such illusions. I remembered that Napoleon

Bonaparte had paused to spend a night alone here during his conquest

of Egypt in the late eighteenth century. The next morning he had

emerged pale and shaken, having experienced something which had

profoundly disturbed him but about which he never afterwards

spoke.22

22

Reported in P. W. Roberts,

River in the Desert: Modern Travels in

Ancient Egypt, Random House, New York and Toronto, 1993, p. 115.

Had he tried to sleep in the sarcophagus?

Acting on impulse, I climbed into the granite coffer and lay down,

face upwards, my feet pointed towards the south and my head to the

north.

Napoleon was a little guy, so he must have fitted comfortably. There

was plenty of room for me too. But had Khufu been here as well?

I relaxed and tried not to worry about the possibility of one of the

pyramid guards coming in and finding me in this embarrassing and

probably illegal position. Hoping that I would remain undisturbed

for a few minutes, I folded my hands across my chest and gave voice

to a sustained low-pitched tone—something I had tried out several

times before at other points in the King’s Chamber. On those

occasions, in the centre of the floor, I had noticed that the walls

and ceiling seemed to collect the sound, to gather and to amplify it

and project it back at me so that I could sense the returning

vibrations through my feet and scalp and skin.

Now in the sarcophagus I was aware of very much the same effect,

although seemingly amplified and concentrated many times over. It

was like being in the sound-box of some giant, resonant musical

instrument designed to emit for ever just one reverberating note.

The sound was intense and quite disturbing. I imagined it rising out

of the coffer and bouncing off the red granite walls and ceiling of

the King’s Chamber, shooting up through the northern and southern

‘ventilation’ shafts and spreading across the Giza plateau like a

sonic mushroom cloud.

With this ambitious vision in my mind, and with the sound of my

low-pitched note echoing in my ears and causing the sarcophagus to

vibrate around me, I closed my eyes. When I opened them a few

minutes later it was to behold a distressing sight: six Japanese

tourists of mixed ages and sexes had congregated around the

sarcophagus—two of them standing to the east, two to the west and

one each to the north and south.

They all looked ... amazed. And I was amazed to see them. Because of

recent attacks by armed Islamic extremists there were now almost no

tourists at Giza and I had expected to have the King’s Chamber to

myself.

What does one do in a situation like this?

Gathering as much dignity as I could muster, I stood upright,

smiling and dusting myself off. The Japanese stepped back and I

climbed out of the sarcophagus. Cultivating a businesslike manner,

as though I did things like this all the time, I strolled to the

point two-thirds of the way along the northern wall of the King’s

Chamber where the entrance to what Egyptologists refer to as the

‘northern ventilation shaft’ is located, and began to examine it

minutely.

Some 8 inches wide by 9 inches high, it was, I knew, more than 200

feet in length and emerged into open air at the pyramid’s 103rd

course of masonry. Presumably by design rather than by accident, it

pointed to the circumpolar regions of the northern heavens at an

angle of 32° 30’. This, in the Pyramid Age around 2500 BC, would

have meant that it was directed on the upper culmination of Alpha Draconis, a prominent star in the constellation of Draco.23

Much to my relief the Japanese rapidly completed their tour of the

King’s Chamber and left, stooping, without a backward glance. As

soon as they had gone I crossed over to the other side of the room

to take a look at the southern shaft. Since I had last been here

some months before, its appearance had changed horribly. Its mouth

now contained a massive electrical air-conditioning unit installed

by Rudolf Gantenbrink, who even now was turning his attentions to

the neglected shafts of the Queen’s Chamber.

Since Egyptologists were satisfied that the King’s Chamber shafts

had been built for ventilation purposes, they saw nothing untoward

in using modern technology to improve the efficiency of this task.

Yet wouldn’t horizontal shafts have been more effective than sloping

ones if their primary purpose had been ventilation, and easier to

build?24 It was therefore unlikely to be an accident that the

southern shaft of the King’s Chamber targeted the southern heavens

at 45°.

During the Pyramid Age this was the location for the

meridian transit of Zeta Orionis, the lowest of the three stars of

Orion’s Belt25—an alignment, I was to discover in due course, that

would turn out to be of the utmost significance for future pyramid

research.

23 Robert Bauval, Discussions in Egyptology No. 29, 1994.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid. See also The Orion Mystery, p. 172.

The game-master

Now that I had the Chamber to myself again, I walked over to the

western wall, on the far side of the sarcophagus, and turned to face

east.

The huge room had an endless capacity to generate indications of

mathematical game-playing. For example, its height (19 feet 1 inch)

was

exactly half of the length of its floor diagonal (38 feet 2

inches).26 Moreover, since the King’s Chamber formed a perfect 1 x 2

rectangle, was it conceivable that the pyramid builders were unaware

that they had also made it express and exemplify the ‘golden

section’?

Known as phi, the golden section was another irrational number like

pi that could not be worked out arithmetically. Its value was the

square root of 5 plus 1 divided by 2, equivalent to 1.61803.27 This

proved to be the ‘limiting value of the ratio between successive

numbers in the Fibonacci series—the series of numbers beginning 0,

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13—in which each term is the sum of the two

previous terms.’28

Phi could also be obtained schematically by dividing a line A-B at a

point C in such a way that the whole line A-B was longer than the

first part, A-C, in the same proportion as the first part, A-C, was

longer than the remainder, C-B.29 This proportion, which had been

proven particularly harmonious and agreeable to the eye, had

supposedly been first discovered by the Pythagorean Greeks, who

incorporated it into the Parthenon at Athens. There is absolutely no

doubt, however, that phi illustrated and obtained at least 2000

years previously in the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid at Giza.

26

Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p. 117; The Great Pyramid: Your

Personal Guide, p.

64.

27 John Ivimy, The Sphinx and the Megaliths, Abacus, London, 1976,

p. 118.

28 Ibid.

29 Secrets of the Great Pyramid, p. 191.

At the very beginning of its Dynastic history, Egypt inherited a

system of measures from unknown predecessors. Expressed in these

ancient measures, the floor dimensions of the King’s Chamber (34 ft.

4” x 17 ft. 2”) work out at exactly 20 x 10 royal cubits’, while the

height of the side walls to the ceiling is exactly 11.18 royal

cubits. The semi-diagonal of the floor (A-B) is also exactly 11.18

royal cubits and can be ‘swung up’ to C to confirm the height of the

chamber. Phi is defined mathematically as the square root of 5 + 1 +

2, i.e. 1.618. Is it a coincidence that the distance C-D (i.e. the

wall height of the King’s Chamber plus half the width of its floor)

equals 16.18 royal cubits, thus incorporating the essential digits

of phi?

To understand how it is necessary to envisage the rectangular floor

of the chamber as being divided into two imaginary squares of equal

size, with the side length of each square being given a value of 1.

If either of these two squares were then split in half, thus forming

two new rectangles, and if the diagonal of the rectangle nearest to

the centerline of the King’s Chamber were swung down to the base,

the point where its tip touched the base would be phi, or 1.618, in

relation to the side length (i.e., 1) of the original square.30

(An

alternative way of obtaining phi, also built into the King’s

Chamber’s dimensions, is illustrated on the previous page.)

30 Ibid. See also Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, pp. 117-19.

The Egyptologists considered all this was pure chance. Yet the

pyramid builders had done nothing by chance. Whoever they had been,

I found it

hard to imagine more systematic and mathematically minded people.

I’d had quite enough of their mathematical games for one day. As I

left the King’s Chamber, however, I could not forget that it was

located in line with the 50th course of the Great Pyramid’s masonry

at a height of almost 150 feet above the ground.31

This meant, as

Flinders Petrie pointed out with some astonishment, that the

builders had managed to place it ‘at the level where the vertical

section of the Pyramid was halved, where the area of the horizontal

section was half that of the base, where the diagonal from corner to

corner was equal to the length of the base, and where the width of

the face was equal to half the diagonal of the base’.32

31 The Great Pyramid: Your Personal Guide, p. 64.

32 The Pyramids

and Temples of Gizeh, p. 93.

Confidently and efficiently fooling around with more than six

million tons of stone, creating galleries and chambers and shafts

and corridors more or less at will, achieving near-perfect symmetry,

near-perfect right angles, and near-perfect alignments to the

cardinal points, the mysterious builders of the Great Pyramid had

found the time to play a great many other tricks as well with the

dimensions of the vast monument.

Why did their minds work this way? What had they been trying to say

or do? And why, so many thousands of years after it was built, did

the monument still exert a magnetic influence upon so many people,

from so many different walks of life, who came into contact with it?

There was a Sphinx in the neighbourhood, so I decided that I would

put these riddles to It ...

Back to

Contents

Chapter 39 -

Place of the Beginning

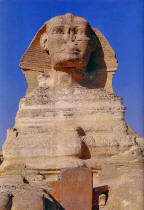

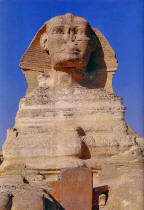

Giza, Egypt, 16 March 1993, 3:30 p.m.

It was mid afternoon by the time I left the Great Pyramid. Retracing

the route that Santha and I had followed the night before when we

had climbed the monument, I walked eastwards along the northern

face, southwards along the flank of the eastern face, clambered over

mounds of rubble and ancient tombs that clustered closely in this

part of the necropolis, and came out on to the sand-covered

limestone bedrock of the Giza plateau, which sloped down towards the

south and east.

At the bottom of this long gentle slope, about half a kilometre from

the south-eastern corner of the Great Pyramid, the Sphinx crouched

in his rock-hewn pit. Sixty-six feet high and more than 240 feet

long, with a head measuring 13 feet 8 inches wide,1 he was, by a

considerable margin, the largest single piece of sculpture in the

world—and the most renowned:

Approaching the monument from the north-west I crossed the ancient

causeway that connected the Second Pyramid with the so-called Valley

Temple of Khafre, a most unusual structure located just 50 feet

south of the Sphinx itself on the eastern edge of the Giza

necropolis.

This Temple had long been believed to be far older than the time of

Khafre. Indeed throughout much of the nineteenth century the

consensus among scholars was that it had been built in remote

prehistory, and had nothing to do with the architecture of dynastic

Egypt.3 What changed all that was the discovery, buried within the

Temple precincts, of a number of inscribed statues of Khafre.

Most

were pretty badly smashed, but one, found upside down in a deep pit

in an antechamber, was almost intact. Life-sized, and exquisitely

carved out of black, jewel-hard diorite, it showed the Fourth

Dynasty pharaoh seated on his throne and gazing with serene

indifference towards infinity.

1 Measurements from The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 106.

2 W. B. Yeats,

‘The Second Coming’.

3 The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 48.

At this point the razor-sharp reasoning of Egyptology was brought to

bear, and a solution of almost awe-inspiring brilliance was worked

out: statues of Khafre had been found in the Valley Temple therefore

the Valley Temple had been built by Khafre. The normally sensible

Flinders

Petrie summed up: ‘The fact that the only dateable remains found in

the Temple were statues of Khafre shows that it is of his period;

since the idea of his appropriating an earlier building is very

unlikely.’4

But why was the idea so unlikely?

Throughout the history of Dynastic Egypt many pharaohs appropriated

the buildings of their predecessors, sometimes deliberately striking

out the cartouches of the original builders and replacing them with

their own.5 There was no good reason to assume that Khafre would

have been deterred from linking himself to the Valley Temple,

particularly if it had not been associated in his mind with any

previous historical ruler but with the great ‘gods’ said by the

Ancient Egyptians to have brought civilization to the Nile Valley in

the distant and mythical epoch they spoke of as the First Time.6

In

such a place of archaic and mysterious power, which he does not

appear to have interfered with in any other way, Khafre might have

thought that the setting up of beautiful and lifelike statues of

himself could bring eternal benefits. And if, among the gods, the

Valley Temple had been associated with Osiris (whom it was every

pharaoh’s objective to join in the afterlife),7 Khafre’s use of

statues to forge a strong symbolic link would be even more

understandable.

4 Ibid., p. 50.

5

Margaret A. Murray, The Splendour that was Egypt, Sidgwick &

Jackson, London, 1987, pp. 160-1.

6 See Part VII, for a full

discussion of the ‘First Time’.

7 Discussed in Part VII; see also

Part III for a comparison of the Osirian rebirth cult and of the

rebirth beliefs of Ancient Mexico.

Temple of the giants

After crossing the causeway, the route I had chosen to reach the

Valley Temple took me through the rubble of a ‘mastaba’ field, where

lesser notables of the Fourth Dynasty had been buried in

subterranean tombs under bench-shaped platforms of stone (mastaba is

a modern Arabic word meaning bench, hence the name given to these

tombs).

I walked along the southern wall of the Temple itself,

recalling that this ancient building was almost as perfectly

oriented north to south as was the Great Pyramid (with an error of

just 12 arc minutes).8

The Temple was square in plan, 147 feet along each side. It was

built in to the slope of the plateau, which was higher in the west

than in the east. In consequence, while its western wall stood only

a little over 20 feet tall, its eastern wall exceeded 40 feet.9

8 The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, p. 47.

9

Measurements from The Pyramids and Temples of Egypt, p. 48, and The

Pyramids of Egypt, p. 108.

Viewed from the south, the impression was of a wedge-shaped

structure, squat and powerful, resting firmly on bedrock. A closer

examination revealed that it incorporated several characteristics

quite alien and inexplicable to the modern eye, which that must have

seemed almost as alien and inexplicable to the Ancient Egyptians.

For a start, there was the stark absence, both inside and out, of

inscriptions and other identifying marks.

In this respect, as the

reader will appreciate, the Valley Temple could be compared with a

few of the other anonymous and frankly undatable monuments on the

Giza plateau, including the great pyramids (and also with a

mysterious structure at Abydos known as the Osireion, which we

consider in detail in a later chapter) but otherwise bore no

resemblance to the typical and well-known products of Ancient

Egyptian art and architecture—all copiously decorated, embellished

and inscribed.10

Another important and unusual feature of the Valley Temple was that

its core structure was built entirely, entirely, of gigantic

limestone megaliths. The majority of these measured about 18 feet

long x 10 feet wide x 8 feet high and some were as large as 30 feet

long x 12 feet wide x 10 feet high.11 Routinely exceeding 200 tons

in weight, each was heavier than a modern diesel locomotive—and

there were hundreds of blocks.12

10

In addition to the three Giza pyramids, the Mortuary Temples of

Khafre and Menkaure can be compared with the Valley Temple in terms

of their absence of adornment and use of megaliths weighing 200 tons

or more.

11 Serpent in the Sky, p. 211; also Mystery of the Sphinx,

NBC-TV, 1993.

12

For block weights see The Pyramids of Egypt, p. 215; Serpent in the

Sky, p. 242; The Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p. 144; The

Pyramids: An Enigma Solved, p. 51; Mystery of the Sphinx, NBC-TV,

1993.

Was this in any way mysterious?

Egyptologists did not seem to think so; indeed few of them had

bothered to comment, except in the most superficial manner—either on

the staggering size of these blocks or the mind-bending logistics of

how they might have been put in place. As we have seen, monoliths of

up to 70 tons, each about as heavy as 100 family-sized cars, had

been lifted to the level of the King’s Chamber in the Great

Pyramid—again without provoking much comment from the Egyptological

fraternity—so the lack of curiosity about the Valley Temple was

perhaps no surprise.

Nevertheless, the block size was truly

extraordinary, seeming to belong not just to another epoch but to

another ethic altogether—one that reflected incomprehensible

aesthetic and structural concerns and suggested a scale of

priorities utterly different from our own.

-

Why, for example, insist

on using these cumbersome 200-ton monoliths when you could simply

slice each of them up into 10 or 20 or 40 or 80 smaller and more manoeuvrable blocks?

-

Why make things so difficult for yourself when

you could achieve much the same visual effect with much less effort?

-

And how had the builders of the Valley Temple lifted these colossal

megaliths to heights of more than 40 feet?

At present there are only two land-based cranes in the world that

could lift weights of this magnitude. At the very frontiers of

construction technology, these are both vast, industrialized

machines, with booms reaching more than 220 feet into the air, which

require on-board counterweights of 160 tons to prevent them from

tipping over. The preparation-time for a single lift is around six

weeks and calls for the skills of specialized teams of up to 20

men.13

13

Personal communication from John Anthony West. See also Mystery of

the Sphinx, NBC-TV.

In other words, modern builders with all the advantages of high-tech

engineering at their disposal, can barely hoist weights of 200 tons.

Was it not, therefore, somewhat surprising that the builders at Giza

had hoisted such weights on an almost routine basis?

Moving closer to the Temple’s looming southern wall I observed

something else about the huge limestone blocks: not only were they

ridiculously large but, as though to complicate still further an

almost impossible task, they had been cut and fitted into

multi-angled jigsaw-puzzle patterns similar to those employed in the

cyclopean stone structures at Sacsayhuaman and Machu Picchu in Peru

(see Part II).

Another point I noticed was that the Temple walls appeared to have

been constructed in two stages. The first stage, most of which was

intact (though deeply eroded), consisted of the strong and heavy

core of 200ton limestone blocks. On to both sides of these had been

grafted a façade of dressed granite which (as we shall see) was

largely intact in the interior of the building but had mainly fallen

away on the outside. A closer look at some of the remaining exterior

facing blocks where they had become detached from the core revealed

a curious fact.

When they had been placed here in antiquity the

backs of these blocks had been cut to fit into and around the deep

coves and scallops of existing weathering patterns on the limestone

core. The presence of those patterns seemed to imply that the core

blocks must have stood here, exposed to the elements, for an immense

span of time before they had been faced with granite.

The Sphinx and the Sphinx Temple with the Valley Temple of Khafre.

Lord of Rostau

I now moved around to the entrance of the Valley Temple, located

near the northern end of the 43-foot high eastern wall. Here I saw

that the granite facing was still in perfect condition, consisting

of huge slabs weighing between 70 and 80 tons apiece which protected

the underlying limestone core blocks like a suit of armour.

Incorporating a tall, narrow, roofless corridor, this dark and

imposing portal ran east to west at first, then made a right-angle

turn to the south, leading me into a spacious antechamber. It was

here that the life-size diorite statue of Khafre had been found,

upside down and apparently ritually buried, at the bottom of a deep

pit.

Lining the entire interior of the antechamber was a majestic jigsaw

puzzle of smoothly polished granite facing blocks (which continued

through the whole building). Exactly like the blocks on some of the

bigger and more bizarre pre-Inca monuments in Peru, these

incorporated multiple, finely chiselled angles in the joints and

presented a complex overall pattern. Of particular note was the way

certain blocks wrapped around corners and were received by

re-entering angles cut into other blocks.

From the antechamber I passed through an elegant corridor which led

west into a spacious T-shaped hall. I found myself standing at the

head of the T looking further westwards along an imposing avenue of

monolithic columns. Reaching almost 15 feet in height and measuring

41 inches on each side, all these columns supported granite beams,

which were again 41 inches square. A row of six further columns,

also supporting beams, ran along the north-south axis of the T; the

overall effect was of massive but refined simplicity.

What was this building for? According to the Egyptologists who

attributed it to Khafre its purpose was obvious. It had been

designed, they said, as a venue for certain of the purification and

rebirth rituals required for the funeral of the pharaoh. The Ancient

Egyptians themselves, however, had left no inscriptions confirming

this.

On the contrary, the only written evidence that has come down

to us indicated that the Valley Temple could not (originally at any

rate) have had anything to do with Khafre, for the simple reason

that it was built before his reign. This written evidence is the

Inventory Stela, (referred to in Chapter Thirty-five), which also

indicated a much greater age for the Great Pyramid and the Sphinx.

What the Inventory Stela had to say about the Valley Temple was that

it had been standing during the reign of Khafre’s predecessor Khufu,

when it had been regarded not as a recent but as a remotely ancient

building. Moreover, it was clear from the context that it was not

thought to have been the work of any earlier pharaoh. Instead, it

was believed to have come down from the ‘First Time’ and to have

been built by the ‘gods’ who had settled in the Nile Valley in that

remote epoch. It was referred to quite explicitly as the ‘House of

Osiris, Lord of Rostau 14 (Rostau being an

archaic name for the Giza

necropolis).15

14 Ancient Records of Egypt, volume I, p. 85.

15

See, for example, Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature,

University of California Press, 1976, volume II, pp. 85-6. 16

Ancient Records of Egypt, volume I, p. 85.

As we shall see in Part VII, Osiris was in many respects the

Egyptian counterpart of Viracocha and Quetzalcoatl, the civilizing

deities of the Andes and of Central America. With them he shared not

only a common mission but a vast heritage of common symbolism. It

seemed appropriate, therefore, that the ‘House’ (or sanctuary, or

temple) of such a wise teacher and lawgiver should have been

established at Giza within sight of the Great Pyramid and in the

immediate vicinity of the Great Sphinx.

Vastly, remotely, fabulously ancient

Following the directions given in the Inventory Stela—which stated

that the Sphinx lay ‘on the north-west of the House of Osiris’16—I

made my way to the north end of the western wall that enclosed the

Valley Temple’s T-shaped hall. I passed through a monolithic doorway

and entered a long, sloping, alabaster floored corridor (also

oriented northwest) which eventually opened out on to the lower end

of the causeway

that led up to the Second Pyramid.

From the edge of the causeway I had an unimpeded view of the Sphinx

immediately to my north. As long as a city block, as high as a

six-storey building it was perfectly oriented due east and thus

faced the rising sun on the two equinoctial days of the year.

Man-headed, lion-bodied, crouched as though ready at last to move

its slow thighs after millennia of stony sleep, it had been carved

in one piece out of a single ridge of limestone on a site that must

have been meticulously preselected.

The exceptional characteristic

of this site, as well as overlooking the Valley of the Nile, was

that its geological make-up incorporated a knoll of hard rock

jutting at least 30 feet above the general level of the limestone

ridge. From this knoll the head and neck of

the Sphinx had been

carved, while beneath it the vast rectangle of limestone that would

be shaped into the body had been isolated from the surrounding

bedrock. The builders had done this by excavating an 18-foot wide,

25-foot deep trench all around it, creating a free-standing

monolith.

The first and lasting impression of the Sphinx, and of its

enclosure, is that it is very, very old—not a mere handful of

thousands of years, like the Fourth Dynasty of Egyptian pharaohs,

but vastly, remotely, fabulously old. This was how the Ancient

Egyptians in all periods of their history regarded the monument,

which they believed guarded the ‘Splendid Place of The Beginning of

all Time’ and which they revered as the focus of ‘a great magical

power extending over the whole region’.17

This, as we have already seen, is the general message of the

Inventory Stela. More specifically, it is also the message of the

‘Sphinx Stela’ erected here in around 1400 BC by Thutmosis IV, an

Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh. Still standing between the paws of the

Sphinx, this granite tablet records that prior to Thutmosis’s rule

the monument had been covered up to its neck in sand. Thutmosis

liberated it by clearing all the sand, and erected the stela to

commemorate his work.18

There have been no significant changes in the climate of the Giza

plateau over the last 5000 years.19 It therefore follows that

throughout this entire period the Sphinx enclosure must have been as

susceptible to sand encroachment as when Thutmosis cleared it—and,

indeed, as it still is today.

Recent history proves that the

enclosure can fill up rapidly if left unattended. In 1818 Captain Caviglia had it cleared of sand for the purposes of his excavations,

and in 1886, when Gaston Maspero came to re-excavate the site, he

was obliged to have it cleared of sand once again. Thirty-nine years

later, in 1925, the sands had returned in full force and the Sphinx

was buried to its neck when the Egyptian Service des Antiquités undertook its clearance and restoration once more.20

-

Does this not suggest that the climate could have been very

different when the Sphinx enclosure was carved out?

-

What would have

been the sense of creating this immense statue if its destiny were

merely to be engulfed by the shifting sands of the eastern Sahara?

-

However, since the Sahara is a young desert, and since the Giza area

in particular was wet and relatively fertile 11,000-15,000 years

ago, is it not worth considering another scenario altogether?

-

Is it

not possible that the Sphinx enclosure was carved out during those

distant green millennia when topsoil was still anchored to the

surface of the plateau by the roots of grasses and shrubs and when

what is now a desert of wind-blown sand more closely resembled the

rolling savannahs of modern Kenya and Tanzania?

17 A History of Egypt, 1902, volume 4, p. 80ff, ‘Stela of the

Sphinx’.

18 Ibid.

19

Karl W. Butzer, Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt: A Study in

Cultural Ecology, University of Chicago Press, 1976.

20

The Pyramids of Egypt, pp. 106-7.

Under such congenial climatic conditions, the creation of a

semi-subterranean monument like the Sphinx would not have outraged