|

Chapter 43 -

Looking for the First Time

Here is what the Ancient Egyptians said about the First Time,

Zep

Tepi, when the gods ruled in their country: they said it was a

golden age1 during which the waters of the abyss receded, the

primordial darkness was banished, and humanity, emerging into the

light, was offered the gifts of civilization.2 They spoke also of

intermediaries between gods and men—the Urshu, a category of lesser

divinities whose title meant ‘the Watchers’.3

And they preserved

particularly vivid recollections of the gods themselves, puissant

and beautiful beings called the Neteru who lived on earth with

humankind and exercised their sovereignty from Heliopolis and other

sanctuaries up and down the Nile. Some of these Neteru were male and

some female but all possessed a range of supernatural powers which

included the ability to appear, at will, as men or women, or as

animals, birds, reptiles, trees or plants.

Paradoxically, their

words and deeds seem to have reflected human passions and

preoccupations. Likewise, although they were portrayed as stronger

and more intelligent than humans, it was believed that they could

grow sick—or even die, or be killed—under certain circumstances.4

1

Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, pp. 263-4; see also Nicolas Grimal,

A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell, Cambridge, 1992, p. 46.

2 New

Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, p. 16.

3

The Gods of the Egyptians, volume I, pp. 84, 161; The Ancient

Egyptian Pyramid Texts, pp. 124, 308.

4 Osiris And The Egyptian

Resurrection, volume I, p. 352.

Records of prehistory

Archaeologists are adamant that the epoch of the gods, which the

Ancient Egyptians, called the First Time, is nothing more than a

myth. The Ancient Egyptians, however, who may have been better

informed about their past than we are, did not share this view.

The

historical records they kept in their most venerable temples

included comprehensive lists of all the kings of Egypt: lists naming

every pharaoh of every dynasty recognized by scholars today.5 Some

of these lists went even further, reaching back beyond the

historical horizon of the First Dynasty into the uncharted depths of

a remote and profound antiquity.

5

Michael Hoffman, Egypt before the Pharaohs, Michael O’Mara Books,

1991, pp. 12-13; Archaic Egypt, pp. 21-3; The Encyclopaedia of

Ancient Egypt, pp. 138-9.

Two lists of kings in this category have survived the ravages of the

ages and, having been exported from Egypt, are now preserved in

European

museums. We shall consider these lists in more detail later in this

chapter. They are known respectively as the Palermo Stone (dating

from the Fifth Dynasty—around the twenty-fifth century BC), and the

Turin Papyrus, a nineteenth Dynasty temple document inscribed in a

cursive form of hieroglyphs known as hieratic and dated to the

thirteenth century BC.6

In addition, we have the testimony of a Heliopolitan priest named

Manetho. In the third century BC he compiled a comprehensive and

widely respected history of Egypt which provided extensive king

lists for the entire dynastic period. Like the Turin Papyrus and the

Palermo Stone, Manetho’s history also reached much further back into

the past to speak of a distant epoch when gods had ruled in the Nile

Valley.

Manetho’s complete text has not come down to us, although copies of

it seem to have been in circulation as late as the ninth century

AD.7 Fortuitously, however, fragments of it were preserved in the

writings of the Jewish chronicler Josephus (AD 60) and of Christian

writers such as Africanus (AD 300), Eusebius (AD 340) and George Syncellus (AD 800).8 These fragments, in the words of the late

Professor Michael Hoffman of the University of South Carolina,

provide the ‘framework for modern approaches to the study of Egypt’s

past’.9

This is quite true.10 Nevertheless, Egyptologists are prepared to

use Manetho only as a source for the historical (dynastic) period

and repudiate the strange insights he provides into prehistory when

he speaks of the remote golden age of the First Time.

-

Why should we

be so selective in our reliance on Manetho?

-

What is the logic of

accepting thirty ‘historical’ dynasties from him and rejecting all

that he has to say about earlier epochs?

-

Moreover, since we know

that his chronology for the historical period has been vindicated by

archaeology,11 isn’t it a bit premature for us to assume that his

pre-dynastic chronology is wrong because excavations have not yet

turned up evidence confirming it?12

6

Egypt before the Pharaohs, pp. 12-13; The Encyclopaedia of Ancient

Egypt, pp. 200,

268.

7 Egypt before the Pharaohs, p. 12.

8

Archaic Egypt, p. 23; Manetho, (trans. W. G. Waddell), William

Heinemann, London, 1940, Introduction pp. xvi-xvii.

9 Egypt before

the Pharaohs, p. 11.

10 Ibid., p. 11-13; Archaic Egypt, pp. 5, 23.

11 See, for example, Egypt before the Pharaohs, pp. 11-13.

12

This is a particularly important point to remember in a discipline

like Egyptology where so much of the record of the past has been

lost through looting, the ravages of time, and the activities of

archaeologists and treasure hunters. Besides, vast numbers of

Ancient Egyptian sites have not been investigated at all, and many

more may lie out of our reach beneath the millennial silt of the

Nile Delta (or beneath the suburbs of Cairo for that matter), and

even at well-studied locations such as the Giza necropolis there are

huge areas—the bedrock beneath the Sphinx for example—which still

await the attentions of the excavator.

Gods, Demigods and Spirits of the Dead

If we are to allow Manetho to speak for himself, we have no choice

but to turn to the texts in which the fragments of his work are

preserved. One of the most important of these is the Armenian

version of the Chronica of Eusebius. It begins by informing us that

it is extracted,

‘from the Egyptian History of Manetho, who composed

his account in three books. These deal with the Gods, the Demigods,

the Spirits of the Dead and the mortal kings who ruled Egypt ...’13

Citing Manetho directly, Eusebius begins by reeling off a list of

the gods which consists, essentially, of the familiar Ennead of Heliopolis—Ra, Osiris, Isis, Horus, Set, and so on:14

These were the first to hold sway in Egypt. Thereafter, the kingship

passed from one to another in unbroken succession ... through 13,900

years — ... After the Gods, Demigods reigned for 1255 years; and

again another line of kings held sway for 1817 years; then came

thirty more kings, reigning for 1790 years; and then again ten kings

ruling for 350 years. There followed the rule of the Spirits of the

Dead ... for 5813 years ...’15

The total of all these periods adds up to 24,925 years and takes us

far beyond the biblical date for the creation of the world (some

time in the fifth millennium BC16). Because it suggested that

biblical chronology was wrong, this created difficulties for

Eusebius, a staunchly Christian commentator. But, after a moment’s

thought, he overcame the problem in an inspired way:

‘The year I

take to be a lunar one, consisting, that is, of 30 days: what we now

call a month the Egyptians used formerly to style a year ...’17

Of course they did no such thing.18 By means of this sleight of

hand, however, Eusebius and others succeeded in boiling down Manetho’s grand pre-dynastic span of almost 25,000 years into a

sanitized dollop a bit over 2000 years which fits comfortably into

the 2242 years orthodox biblical chronology allows between Adam and

the Flood.19

A different technique for downplaying the disturbing chronological

implications of Manetho’s evidence is employed by the monk George Syncellus (c. AD 800). This commentator, who relies entirely on

invective, writes,

‘Manetho, chief priest of the accursed temples of

Egypt [tells us] of gods who never existed. These, he says, reigned

for 11,895 years ...’20

13 Manetho, p. 3.

14 Ibid., pp. 3-5.

15 Ibid., p. 5.

16 Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1991, 12:214-15.

17 Manetho, p. 5.

18

There is absolutely no evidence that the Ancient Egyptians ever

confused years and months, or styled one as the other; ibid, p. 4,

note 2.

19 Ibid., p. 7. 20 Ibid., p. 15.

Several other curious and contradictory numbers crop up in the

fragments. In particular, Manetho is repeatedly said to have given

the

enormous figure of 36,525 years for the entire duration of the

civilization of Egypt from the time of the gods down to the end of

the thirtieth (and last) dynasty of mortal kings.21 This figure of

course, incorporates the

365.25 days of the Sothic year (the interval between two consecutive

heliacal risings of Sirius, as described in the last chapter). More

likely by design than by accident, it also represents 25 cycles of

1460 Sothic years, and 25 cycles of 1461 calendar years (since the

ancient Egyptian civil calendar was constructed around a ‘vague

year’ of 365 days exactly).22

21 Ibid., p. 231; see also The Splendour that was Egypt, p. 12.

22

Like the Maya, (see Part III), the Ancient Egyptians made use for

administrative purposes of a civil calendar year (or vague year) of

365 days exactly. See Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico, p. 151, for

further details on the Maya vague year. The Ancient Egyptian civil

calendar year was geared to the Sothic year so that both would

coincide on the same day/month position once every 1461 calendar

years.

What, if anything, does all this mean? It’s hard to be sure. Out of

the welter of numbers and interpretations, however, there is one

aspect of Manetho’s original message that comes through loud and

clear. Irrespective of everything we have been taught about the

orderly progress of history, what he seems to be telling us is that

civilized beings (either gods or men) were present in Egypt for an

immensely long period before the advent of the First Dynasty around

3100 BC.

Diodorus Siculus and Herodotus

In this assertion, Manetho finds much support among classical

writers.

In the first century BC, for example, the Greek historian Diodorus

Siculus visited Egypt. He is rightly described by C.H. Oldfather,

his most recent translator, as ‘an uncritical compiler who used good

sources and reproduced them faithfully’.23 In plain English, what

this means is that Diodorus did not try to impose his prejudices and

preconceptions on the material he collected. He is therefore

particularly valuable to us because his informants included Egyptian

priests whom he questioned about the mysterious past of their

country.

This is what they told him:

‘At first gods and heroes ruled Egypt for a little less than 18,000

years, the last of

the gods to rule being Horus, the son of Isis ... Mortals have been

kings of their

country, they say, for a little less than 5000 years ...24

Let us review these figures ‘uncritically’ and see what they add up

to. Diodorus was writing in the first century BC. If we journey back

from there for the 5000 years during which the ‘mortal kings’

supposedly ruled, we get to around 5100 BC. If we go even further

back to the beginning of the age of ‘gods and heroes’, we find that

we have arrived at 23,100 BC, when the world was still firmly in the

grip of the last Ice Age.

23

Diodorus Siculus, translated by C.H. Oldfather, Harvard University

Press, 1989, jacket text.

24 Ibid., volume I, p. 157.

Long before Diodorus, Egypt was visited by another and more

illustrious Greek historian: the great Herodotus, who lived in the

fifth century BC. He too, it seems, consorted with priests and he

too managed to tune in to traditions that spoke of the presence of a

high civilization in the Nile Valley at some unspecified date in

remote antiquity.

Herodotus outlines these traditions of an immense

prehistoric period of Egyptian civilization in Book II of his

History. In the same document he also hands on to us, without

comment, a peculiar nugget of information which had originated with

the priests of Heliopolis:

During this time, they said, there were four occasions when the sun

rose out of his

wonted place—twice rising where he now sets, and twice setting where

he now

rises.25

What is this all about?

According to the French mathematician Schwaller de Lubicz, what

Herodotus is transmitting to us (perhaps unwittingly) is a veiled

and garbled reference to a period of time—that is, to the time that

it takes for sunrise on the vernal equinox to precess against the

stellar background through one and a half complete cycles of the

zodiac.26

25

The History, pp. 193-4. In the first century AD a similar tradition

was recorded by the Roman scholar Pomponious Mela: ‘The Egyptians

pride themselves on being the most ancient people in the world. In

their authentic annals one may read that since they have been in

existence, the course of the stars has changed direction four times,

and that the sun has set twice in the part of the sky where it rises

today.’ (Pomponious Mela, De Situ Orbis.)

26 Sacred Science, p. 87

As we have seen, the equinoctial sun spends roughly 2160 years in

each of the twelve zodiacal constellations. A full cycle of

precession of the equinoxes therefore takes almost 26,000 years to

complete (12 x 2160 years). It follows that one and a half cycles

takes nearly 39,000 years (18 x 2160 years).

In the time of Herodotus the sun on the vernal equinox rose due east

at dawn against the stellar background of Aries—at which moment the

constellation of Libra was ‘in opposition’, lying due west where the

sun would set twelve hours later. If we wind the clock of precession

back half a cycle, however—six houses of the zodiac or approximately

13,000 years—we find that the reverse configuration prevails: the

vernal sun now rises due east in Libra while Aries lies due west in

opposition. A further 13,000 years back, the situation reverses

itself once more, with the vernal sun rising again in Aries and with

Libra in opposition.

This takes us to 26,000 years before Herodotus.

If we then step back another 13,000 years, another half precessional

cycle, to 39,000 years before Herodotus, the vernal sunrise returns

to Libra, and Aries is again in opposition.

The point is this: with 39,000 years we have an expanse of time

during which the sun can be described as ‘twice rising where he now

sets’, i.e. in

Libra in the time of Herodotus (and again at 13,000 and at 39,000

years earlier), and as ‘twice setting where he now rises’, i.e. in

Aries in the time of Herodotus (and again at 13,000 and 39,000 years

earlier).27

27 As the following table makes clear:

If Schwaller’s interpretation is correct—and there is

every reason to suppose it is—it suggests that the Greek historian’s

priestly informants must have had access to accurate records of the

precessional motion of the sun going back at least 39,000 years

before their own era.

The Turin Papyrus and the Palermo Stone

The figure of 39,000 years accords surprisingly closely with the

testimony of the Turin Papyrus (one of the two surviving Ancient

Egyptian king lists that extends back into prehistoric times before

the First Dynasty).

Originally in the collection of the king of Sardinia, the brittle

and crumbling 3000-year-old papyrus was sent in a box, without

packing, to its present home in the Museum of Turin. As any

schoolchild could have predicted, it arrived broken into countless

fragments. Scholars were obliged to work for years to piece together

and make sense of what remained, and they did a superb job.28

Nevertheless, more than half the contents of this precious record

proved impossible to reconstruct.29

What might we have learned about the First Time if the Turin Papyrus

had remained intact?

The surviving fragments are tantalizing. In one register, for

example, we read the names often Neteru with each name inscribed in

a cartouche (oblong enclosure) in much the same style adopted in

later periods for the historical kings of Egypt. The number of years

that each Neter was believed to have reigned was also given, but

most of these numbers are missing from the damaged document.30

In another column there appears a list of the mortal kings who ruled

in upper and lower Egypt after the gods but prior to the supposed

unification of the kingdom under Menes, the first pharaoh of the

First Dynasty, in 3100 BC.

From the surviving fragments it is possible to

372 establish that nine ‘dynasties’ of these pre-dynastic pharaohs

were mentioned, among which were ‘the Venerables of Memphis’, ‘the

Venerables of the North’ and, lastly, the Shemsu Hor (the

Companions, or Followers, of Horus) who ruled until the time of

Menes.

The final two lines of the column, which seem to represent a

summing up or inventory, are particularly provocative. They read:

‘... Venerables Shemsu-Hor, 13,420 years; Reigns before the

Shemsu-Hor, 23,200 years; Total 36,620 years’.31

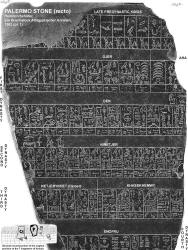

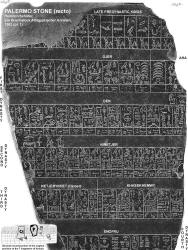

The other king list that deals with prehistoric times is the Palermo

Stone, which does not take us as far back into the past as the Turin

Papyrus. The earliest of its surviving registers record the reigns

of 120 kings who ruled in upper and lower Egypt in the late

pre-dynastic period: the centuries immediately prior to the

country’s unification in 3100 BC.32

Once again, however, we really

have no idea how much other information, perhaps relating to far

earlier periods, might originally have been inscribed on this

enigmatic slab of black basalt, because it, too, has not come down

to us intact. Since 1887 the largest single part has been preserved

in the Museum of Palermo in Sicily; a second piece is on display in

Egypt in the Cairo Museum; and a third much smaller fragment is in

the Petrie Collection at the University of London.33

These are

reckoned by archaeologists to have been broken out of the centre of

a monolith which would originally have measured about seven feet

long by two feet high (stood on its long side).34 Furthermore, as

one authority has observed:

It is quite possible—even probable—that many more pieces of this

invaluable monument remain, if we only knew where to look. As it is

we are faced with the tantalising knowledge that a record of the

name of every king of the Archaic Period existed, together with the

number of years of his reign and the chief events which occurred

during his occupation of the throne. And these events were compiled

in the Fifth Dynasty, only about 700 years after the Unification, so

that the margin of error would in all probability have been very

small ...’35

The late Professor Walter Emery, whose words these are, was

naturally concerned about the absence of much-needed details

concerning the Archaic Period, 3200 BC to 2900 BC,36 the focus of

his own specialist interests. We should also spare a thought,

however, for what an intact

Palermo Stone might have told us about even earlier epochs, notably

Zep Tepi—the golden age of the gods.

28

See, for example, Sir A.H. Gardner, The Royal Cannon of Turin,

Griffith Institute, Oxford.

29 Archaic Egypt, p. 4.

30 For further

details, Sacred Science, p. 86.

31 Ibid., p. 86. See also Egyptian Mysteries, p. 68.

32 Archaic

Egypt, p. 5; Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egypt, p. 200.

33 Archaic

Egypt, p. 5; Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1991, 9:81.

34 Encyclopaedia

of Ancient Egypt, p. 200.

35 Archaic Egypt, p. 5.

36 Egypt to the End

of the Old Kingdom, p. 12.

The deeper we penetrate into the myths and memories of Egypt’s long

past, and the closer we approach to the fabled First Time, the

stranger the landscapes that surround us become ... as we shall see.

Back to

Contents

Chapter 44 -

Gods of the First Time

According to Heliopolitan theology, the nine original gods who

appeared in Egypt in the First Time were Ra, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut,

Osiris, Isis, Nepthys and Set. The offspring of these deities

included well-known figures such as Horus and Anubis. In addition,

other companies of gods were recognized, notably at Memphis and

Hermopolis, where there were important and very ancient cults

dedicated to Ptah and to Thoth.1

These First Time deities were all

in one sense or another gods of creation who had given shape to

chaos through their divine will. Out of that chaos they formed and

populated the sacred land of Egypt,2 wherein, for many thousands of

years, they ruled among men as divine pharaohs.3

What was ‘chaos’?

The Heliopolitan priests who spoke to the Greek historian Diodorus

Siculus in the first century BC put forward the thought-provoking

suggestion that ‘chaos’ was a flood—identified by Diodorus with the

earth-destroying flood of Deucalion, the Greek Noah figure: 4

In general, they say that if in the flood which occurred in the time

of Deucalion most living things were destroyed, it is probable that

the inhabitants of southern Egypt survived rather than any others

... Or if, as some maintain, the destruction of living things was

complete and the earth then brought forth again new forms of

animals, nevertheless, even on such a supposition, the first genesis

of living things fittingly attaches to this country ...5

Why should Egypt have been so blessed? Diodorus was told that it had

something to do with its geographical situation, with the great

exposure of its southern regions to the heat of the sun, and with

the vastly increased rainfall which the myths said the world had

experienced in the aftermath of the universal deluge:

‘For when the

moisture from the abundant rains which fell among other peoples was

mingled with the intense heat which prevails in Egypt itself ... the

air became very well tempered for the first generation of all living

things ...’6

1

Kingship and the Gods, pp. 181-2; The Encyclopaedia of Ancient

Egypt, pp. 209, 264; Egyptian Myths, pp. 18-22. See also T. G. H.

James, An Introduction to Ancient Egypt, British Museum

Publications, London, 1979, p. 125ff.

2

Cyril Aldred, Akhenaton, Abacus, London, 1968, p. 25: ‘It was

believed that the gods had ruled in Egypt after first making it

perfect.’

3

Kingship and the Gods, pp. 153-5; Egyptian Myths, pp. 18-22;

Egyptian Mysteries, pp. 8-11; New Larousse Encyclopaedia of

Mythology, pp. 10-28. 4 See Part IV.

5 Diodorus Siculus, volume I,

p. 37.

6 Ibid.

Curiously enough, Egypt does enjoy a special geographical situation:

as

is well known, the latitude and longitude lines which intersect just

beside the Great Pyramid (30° north and 31° east) cross more dry

land than any others.7

Curiously, too, at the end of the last Ice

Age, when millions of square miles of glaciation were melting in

northern Europe, when rising sea levels were flooding coastal areas

all around the globe, and when the huge volume of extra moisture

released into the atmosphere through the evaporation of the ice

fields was being dumped as rain, Egypt benefited for several

thousands of years from an exceptionally humid and fertile climate.8

It is not difficult to see how such a climate might indeed have been

remembered as ‘well tempered for the first generation of all living

things’.

The question therefore has to be asked: whose information about the

past are we receiving from Diodorus, and is the apparently accurate

description of Egypt’s lush climate at the end of the last Ice Age a

coincidence, or is an extremely ancient tradition being transmitted

to us here—a memory, perhaps, of the First Time?

7 Mystic Places, Time-Life Books,

1987, p. 62.

8 Early Hydraulic Civilization in

Egypt, p. 13; Egypt before the Pharaohs, pp. 27, 261.

Breath of the divine serpent

Ra was believed to have been the first king of the First Time and

ancient myths say that as long as he remained young and vigorous he

reigned peacefully. The passing years took their toll on him,

however, and he is depicted at the end of his rule as an old,

wrinkled, stumbling man with a trembling mouth from which saliva

ceaselessly dribbles.9

Shu followed Ra as king on earth, but his reign was troubled by

plots and conflicts. Although he vanquished his enemies he was in

the end so ravaged by disease that even his most faithful followers

revolted against him: ‘Weary of reigning, Shu abdicated in favour of

his son Geb and took refuge in the skies after a terrifying tempest

which lasted nine days ...’10

Geb, the third divine pharaoh, duly succeeded Shu to the throne. His

reign was also troubled and some of the myths describing what took

place reflect the odd idiom of the Pyramid Texts in which a

non-technical vocabulary seems to wrestle with complex technical and

scientific imagery.

For example, one particularly striking tradition

speaks of a ‘golden box’ in which Ra had deposited a number of

objects—described, respectively, as his ‘rod’ (or cane), a lock of

his hair, and his uraeus (a rearing cobra with its hood extended,

fashioned out of gold, which was worn on the royal head-dress).11

9 New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, p. 11.

10 Ibid., p.

13.

11 Ibid., pp. 14-15.

A powerful and dangerous talisman, this box, together with its

bizarre

contents, remained enclosed in a fortress on the ‘eastern frontier’

of Egypt until a great many years after Ra’s ascent to heaven. When

Geb came to power he ordered that it should be brought to him and

unsealed in his presence. In the instant that the box was opened a

bolt of fire (described as the ‘breath of the divine serpent’)

ushered from it, struck dead all Geb’s companions and gravely burned

the god-king himself.12

It is tempting to wonder whether what we are confronted by here

might not be a garbled account of a malfunctioning man-made device:

a confused, awe-stricken recollection of a monstrous instrument

devised by the scientists of a lost civilization. Weight is added to

such extreme speculations when we remember that this is by no means

the only golden box in the ancient world that functioned like a

deadly and unpredictable machine.

It has a number of quite unmissable similarities to the Hebrews’ enigmatic

Ark of the

Covenant (which also struck innocent people dead with bolts of fiery

energy, which also was ‘overlaid round about with gold’, and which

was said to have contained not only the two tablets of the Ten

Commandments but ‘the golden pot that had manna, and Aaron’s

rod.’)13

A proper look at the implications of all these weird and wonderful

boxes (and of other ‘technological’ artifacts referred to in ancient

traditions) is beyond the scope of this book. For our purposes here

it is sufficient to note that a peculiar atmosphere of dangerous and

quasi-technological wizardry seems to surround many of the gods of

the Heliopolitan Ennead.

Isis, for example (wife and sister of Osiris and mother of Horus)

carries a strong whiff of the science lab. According to the Chester

Beatty Papyrus in the British Museum she was ‘a clever woman ...

more intelligent than countless gods ... She was ignorant of nothing

in heaven and earth.’14

Renowned for her skilful use of witchcraft

and magic, Isis was particularly remembered by the Ancient Egyptians

as,

‘strong of tongue’, that is being in command of words of power

‘which she knew with correct pronunciation, and halted not in her

speech, and was perfect both in giving the command and in saying the

word’.15

In short, she was believed, by means of her voice alone, to

be capable of bending reality and overriding the laws of physics.

These same powers, though perhaps in greater degree, were attributed

to the wisdom god Thoth who although not a member of the

Heliopolitan Ennead is recognized in the Turin Papyrus and other

ancient records as the sixth (or sometimes as the seventh) divine

pharaoh of Egypt.16

12 Ibid.

13

Hebrews 9:4. For details of the Ark’s baleful powers see Graham

Hancock, The Sign and the Seal, Mandarin, London, 1993, Chapter 12,

p. 273ff.

14 Cited in Egyptian Myths, p. 44.

15

Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, Kegan Paul, Trench, London,

1901, p. 5; The Gods of the Egyptians, volume II, p. 214.

16

New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, p. 27. If Set’s usurpation

is included as a

reign, we have seven divine pharaohs up to and including Thoth

(i.e., Ra, Shu, Geb, Osiris, Set, Horus, Thoth).

Frequently represented on temple and tomb walls as an ibis, or an

ibis-headed man, Thoth was venerated as the regulative force

responsible for all heavenly calculations and annotations, as the

lord and multiplier of time, the inventor of the alphabet and the

patron of magic. He was particularly associated with astronomy,

mathematics, surveying and geometry, and was described as ‘he who

reckons in heaven, the counter of the stars and the measurer of the

earth’.17

He was also regarded as a deity who understood the

mysteries of ‘all that is hidden under the heavenly vault’, and who

had the ability to bestow wisdom on selected individuals. It was

said that he had inscribed his knowledge in secret books and hidden

these about the earth, intending that they should be sought for by

future generations but found ‘only by the worthy’—who were to use

their discoveries for the benefit of mankind.18

What stands out most clearly about Thoth, therefore, in addition to

his credentials as an ancient scientist, is his role as a benefactor

and civilizer.19 In this respect he closely resembles his

predecessor Osiris, the high god of the Pyramid Texts and the fourth

divine pharaoh of Egypt,

‘whose name becometh Sah [Orion], whose leg

is long, and his stride extended, the President of the Land of the

South ...’20

Osiris and the Lords of Eternity

Occasionally referred to in the texts as a neb tem, or ‘universal

master’,21 Osiris is depicted as human but also superhuman,

suffering but at the same time commanding. Moreover, he expresses

his essential dualism by ruling m heaven (as the constellation of

Orion) and on earth as a king among men.

Like Viracocha in the Andes

and Quetzalcoatl in Central America, his ways are subtle and

mysterious. Like them, he is exceptionally tall and always depicted

wearing the curved beard of divinity.22

And like them too, although

he has supernatural powers at his

disposal, he avoids the use of force wherever possible.23

17

The Gods of the Egyptians, volume I, p. 400; Garth Fowden, The

Egyptian Hermes, Cambridge University Press, 1987, pp. 22-3. see

also From Fetish to God in Ancient Egypt, pp. 121-2; Egyptian Magic,

pp. 128-9; New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, pp. 27-8.

18

Manetho, quoted by the neo-Platonist Iamblichus. See Peter

Lemesurier, The Great Pyramid Decoded, Element Books, 1989, p. 15;

The Egyptian Hermes, p. 33.

19

See, for example, Diodorus Siculus, volume I, p. 53, where Thoth

(under his Greek name of Hermes) is described as being ‘endowed with

unusual ingenuity for devising things capable of improving the

social life of man’.

20 Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, volume

II, p. 307.

21

Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, p. 179; New Larousse Encyclopaedia

of Mythology,

p. 16.

22

New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, pp. 9-10, 16; Encyclopaedia

of Ancient Egypt, p. 44; The Gods of the Egyptians, volume II, pp.

130-1; From Fetish to God in

Ancient Egypt, p. 190; Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, p. 230.

We saw in Chapter Sixteen that Quetzalcoatl, the god-king of the

Mexicans, was believed to have departed from Central America by sea,

sailing away on a raft of serpents. It is therefore hard to avoid a

sense of déjà vu when we read in the Egyptian Book of the Dead that

the abode of Osiris also ‘rested on water’ and had walls made of

‘living serpents’.24 At the very least, the convergence of symbolism

linking these two gods and two far-flung regions is striking.

There are other obvious parallels as well.

The central details of the story of Osiris have been recounted in

earlier chapters and we need not go over them again. The reader will

not have forgotten that this god—once again like Quetzalcoatl and

Viracocha—was remembered principally as a benefactor of mankind, as

a bringer of enlightenment and as a great civilizing leader.25

He

was credited, for example, with having abolished cannibalism and was

said to have introduced the Egyptians to agriculture—in particular

to the cultivation of wheat and barley—and to have taught them the

art of fashioning agricultural implements.

Since he had an especial

liking for fine wines (the myths do not say where he acquired this

taste), he made a point of ‘teaching mankind the culture of the

vine, as well as the way to harvest the grape and to store the wine

...’26 In addition to the gifts of good living he brought to his

subjects, Osiris helped to wean them ‘from their miserable and

barbarous manners’ by providing them with a code of laws and

inaugurating the cult of the gods in Egypt.27

When he had set everything in order, he handed over the control of

the kingdom to Isis, quit Egypt for many years, and roamed about the

world with the sole intention, Diodorus Siculus was told,

of visiting all the inhabited earth and teaching the race of men how

to cultivate the vine and sow wheat and barley; for he supposed that

if he made men give up their savagery and adopt a gentle manner of

life he would receive immortal honours because of the magnitude of

his benefactions ...28

Osiris travelled first to Ethiopia, where he taught tillage and

husbandry to the primitive hunter-gatherers he encountered. He also

undertook a number of large-scale engineering and hydraulics works:

‘He built canals, with flood gates and regulators ... he raised the

river banks and took precautions to prevent the Nile from

overflowing ...’29

Later he made his

way to Arabia and thence to India, where he established many cities.

Moving on to Thrace he killed a barbarian king for refusing to adopt

his system of government. This was out of character; in general,

Osiris was remembered by the Egyptians for having

forced no man to carry out his instructions, but by means of gentle

persuasion and an appeal to their reason he succeeded in inducing

them to practice what he preached. Many of his wise counsels were

imparted to his listeners in hymns and songs, which were sung to the

accompaniment of instruments of music.’ 30

Once again the parallels with Quetzalcoatl and Viracocha are hard to

avoid. During a time of darkness and chaos—quite possibly linked to

a flood—a bearded god, or man, materializes in Egypt (or Bolivia, or

Mexico). He is equipped with a wealth of practical and scientific

skills, of the kind associated with mature and highly developed

civilizations, which he uses unselfishly for the benefit of

humanity.

He is instinctively gentle but capable of great firmness

when necessary. He is motivated by a strong sense of purpose and,

after establishing his headquarters at Heliopolis (or Tiahuanaco, or

Teotihuacan), he sets forth with a select band of companions to

impose order and to reinstate the lost balance of the world.31

23 Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, volume I, p. 2.

24 Chapter CXXV, cited in ibid., volume II, p. 81.

25

See Parts II and III for Quetzalcoatl and Viracocha. A good summary

of Osiris’s civilizing attributes is the New Larousse Encyclopaedia

of Mythology, p. 16. See also Diodorus Siculus, pp. 47-9; Osiris and

the Egyptian Resurrection, volume I, pp. 1-12.

26 Diodorus Siculus,

p. 53.

27 Ibid.; Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, volume I, p.

2.

28 Diodorus Siculus, p. 55.

29 Osiris and the Egyptian

Resurrection, volume I, p. 11.

30 Ibid., p. 2.

31

Ibid., 2-11. For Quetzalcoatl and Viracocha see Parts II and III.

Interestingly enough, Osiris was said to have been accompanied on

his civilizing mission by two ‘openers of the way’: (Diodorus

Siculus page 57), ‘Anubis and Macedo, Anubis wearing a dog’s skin

and Macedo the fore-parts of a wolf ...’

Leaving aside for the present the issue of whether we are dealing

here with gods or men, with figments of the primitive imagination or

with flesh-and-blood beings, the fact remains that the myths always

speak of a company of civilizers: Viracocha has his ‘companions’, as

have both Quetzalcoatl and Osiris.

Sometimes there are fierce

internal conflicts within these groups, and perhaps struggles for

power: the battles between Seth and Horus, and between

Tezcatlipoca

and Quetzalcoatl are obvious examples. Moreover, whether the

mythical events unfold in Central America, or in the Andes, or in

Egypt, the upshot is also always pretty much the same: the civilizer

is eventually plotted against and either driven out or killed.

The myths say that Quetzalcoatl and Viracocha never came back

(although, as we have seen, their return to the Americas was

expected at the time of the Spanish conquest). Osiris, on the other

hand, did come back. Although he was murdered by Set soon after the

completion of his worldwide mission to make men ‘give up their

savagery’, he won eternal life through his resurrection in the

constellation of Orion as the all-powerful god of the dead.

Thereafter, judging souls and providing an immortal example of

responsible and benevolent kingship, he dominated the religion (and

the culture) of Ancient Egypt for the entire span of its known

history.

Serene stability

Who can guess what the civilizations of the Andes and of Mexico

might have achieved if they too had benefited from such powerful

symbolic continuity. In this respect, however, Egypt is unique.

Indeed, although the Pyramid Texts and other archaic sources

recognize a period of disruption and attempted usurpation by Set

(and his seventy-two ‘precessional’ conspirators), they also depict

the transition to the reigns of Horus, Thoth and the later divine

pharaohs as being relatively smooth and inevitable.

This transition was mimicked, through thousands of years, by the

mortal kings of Egypt. From the beginning to the end, they saw

themselves as the lineal descendants and living representatives of

Horus, son of Osiris. As generation succeeded generation, it was

supposed that each deceased pharaoh was reborn in the sky as ‘an

Osiris’ and that each successor to the throne became a ‘Horus’.32

This simple, refined, and stable scheme was already fully evolved

and in place at the beginning of the First Dynasty—around 3100 BC.33

Scholars accept this; the majority also accept that what we are

dealing with here is a highly developed and sophisticated

religion.34 Strangely, very few Egyptologists or archaeologists have

questioned where and when this religion took shape.

Is it not to defy logic to suppose that well-rounded social and

metaphysical ideas like those of the Osiris cult sprung up fully

formed in 3100 BC, or that they could have taken such perfect shape

in the 300 years which Egyptologists sometimes grudgingly allow for

them to have done so?35

There must have been a far longer period of

development than that, spread over several thousands rather than

several hundreds of years. Moreover, as we have seen, every

surviving record in which the Ancient Egyptians speak directly about

their past asserts that their civilization was a legacy of ‘the

gods’ who were ‘the first to hold sway in Egypt’.36

The records are not internally consistent: some attribute much

greater antiquity to the civilization of Egypt than others. All,

however, clearly and firmly direct our attention to an epoch far,

far in the past—anything from 8000 to almost 40,000 years before the

foundation of the First Dynasty.

Archaeologists insist that no material artefacts have ever been

found in Egypt to suggest that an evolved civilization existed at

such early dates, but this is not strictly true. As we saw in Part

VI, a handful of objects and structures exist which have not yet

been conclusively dated by any

scientific means.

32

Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, volume II, p. 273. See also in

general, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts.

33 Archaic Egypt, p.

122; Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, p. 98.

34 See, in general,

Kingship and the Gods; Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection; The

Gods of the Egyptians.

35 Archaic Egypt, p. 38.

36 Manetho, p. 5.

The ancient city of Abydos conceals one of the most extraordinary of

these undatable enigmas ...

Back to

Contents

Chapter 45

-

The Works of Men and Gods

Among the numberless ruined temples of Ancient Egypt, there is one

that is unique not only for its marvellous state of preservation,

which (rare indeed!) includes an intact roof, but for the fine

quality of the many acres of beautiful reliefs that decorate its

towering walls. Located at Abydos, eight miles west of the present

course of the Nile, this is the Temple of Seti I, a monarch of the

illustrious nineteenth Dynasty, who ruled from 1306-1290 BC.1

Seti is known primarily as the father of a famous son: Ramesses II

(1290-1224 BC), the pharaoh of the biblical Exodus.2 In his own

right, however, he was a major historical figure who conducted

extensive military campaigns outside Egypt’s borders, who was

responsible for the construction of several fine buildings and who

carefully and conscientiously refurbished and restored many older

ones.3

His temple at Abydos, which was known evocatively as ‘The

House of Millions of Years’, was dedicated to Osiris,4 the ‘Lord of

Eternity’, of whom it was said in the Pyramid Texts:

You have gone, but you will return, you have slept, but you will

awake, you have died, but you will live ... Betake yourself to the

waterway, fare upstream ... travel about Abydos in this spirit-form

of yours which the gods commanded to belong to you.5

1 Atlas of Ancient Egypt, p. 36.

2

Dates from Atlas of Ancient Egypt. For further data on Ramesses II

as the pharaoh of the exodus see Profuses K. A. Kitchen, Pharaoh

Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, Aris and Phillips,

Warminster, 1982, pp. 70-1.

3 See, for example, A Biographical

Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, pp. 135-7.

4 Traveller’s Key to Ancient

Egypt, p. 384.

5 The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, pp. 285, 253.

Atef Crown

It was eight in the morning, a bright, fresh hour in these

latitudes, when I entered the hushed gloom of the Temple of Seti I.

Sections of its walls were floor-lit by low-wattage electric bulbs;

otherwise the only illumination was that which the pharaoh’s

architects had originally planned: a few isolated shafts of sunlight

that penetrated through slits in the outer masonry like beams of

divine radiance.

Hovering among the motes of dust dancing in those

beams, and infiltrating the heavy stillness of the air amid the

great columns that held up the roof of the Hypostyle

Hall, it was easy to imagine that the spirit-form of Osiris could

still be present. Indeed, this was more than just imagination

because Osiris was physically present in the astonishing symphony of

reliefs that adorned the walls—reliefs that depicted the once and

future civilizer-king in his role as god of the dead, enthroned and

attended by Isis, his beautiful and mysterious sister.

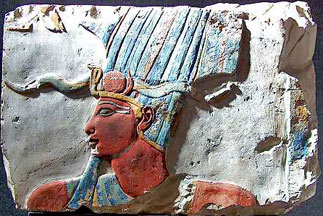

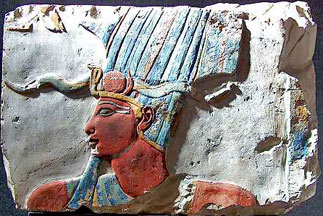

In these scenes Osiris wore a variety of different and elaborate

crowns which I studied closely as I walked from relief to relief.

Crowns similar to these in many respects had been important parts of

the wardrobe of all the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt, at least on the

evidence of reliefs depicting them. Strangely, however, in all the

years of intensive excavations, archaeologists had not found a

single example of a royal crown, or a small part of one, let alone a

specimen of the convoluted ceremonial headdresses associated with

the gods of the First Time.6

Of particular interest was the Atef crown. Incorporating the uraeus,

the royal serpent symbol (which in Mexico was a rattlesnake but in

Egypt was a hooded cobra poised to strike), the central core of this

strange contraption was recognizable as an example of the hedjet,

the white skittle-shaped war helmet of upper Egypt (again known only

from reliefs).

Rearing up on either side of this core were what

seemed to be two thin leaves of metal, and at the front was an

attached device, consisting of two wavy blades, which scholars

normally describe as a pair of rams’ horns.7

In several reliefs of the Seti I Temple

Osiris was depicted wearing

the Atef crown, which seemed to stand about two feet high. According

to the Ancient Egyptian

Book of the Dead, it had been given to him

by Ra:

‘But on the very first day that he wore it Osiris had much

suffering in his head, and when Ra returned in the evening he found

Osiris with his head angry and swollen from the heat of the Atef

crown. Then Ra proceeded to let out the pus and the blood.’8

All this was stated in a matter-of-fact way, but—when you stopped to

think about it—what kind of crown was it that radiated heat and

caused the skin to haemorrhage and break out in pustulant sores?

6 Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p. 386.

7 The Encyclopaedia of

Ancient Egypt, p. 59.

8

Chapter 175 of the Ancient Egyptian Book of

the Dead, cited in Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, p. 137.

Abydos.

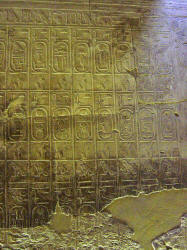

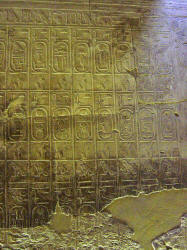

Seventeen centuries of kings

I walked on into the deeper darkness, eventually finding my way to

the Gallery of the Kings. It led off from the eastern edge of the

inner Hypostyle Hall about 200 feet from the entrance to the temple.

To pass through the Gallery was to pass through time itself. On the

wall to my left was a list of 120 of the gods of Ancient Egypt,

together with the names of their principal sanctuaries. On my right,

covering an area of perhaps ten feet by six feet, were the names of

the 76 pharaohs who had preceded Seti I to the throne; each name was

carved in hieroglyphs inside an oval cartouche.

This tableau was known as the ‘Abydos King List’.

Glowing with colours of molten gold, it was designed to be read from left to

right and was divided into five vertical and three horizontal

registers. It covered a grand expanse of almost 1700 years,

beginning around 3000 BC with the reign of Menes, first king of the

First Dynasty, and ending with Seti’s own reign around 1300 BC. At

the extreme left stood two figures exquisitely carved in high

relief: Seti and his young son, the future Ramesses II.

Hypogeum

Belonging to the same class of historical documents as the

Turin

Papyrus and the Palermo Stone, the list spoke eloquently of the

continuity of tradition. An inherent part of that tradition, was the

belief or memory of a First Time, long, long ago, when the gods had

ruled in Egypt.

|

Left half of

the Turin papyrus map |

Right half

of the Turin papyrus map |

|

Palermo

Stone |

Principal among those gods was Osiris, and it was

therefore appropriate that the Gallery of the Kings should provide

access to a second corridor, leading to the rear of the temple where

a marvellous building was located—one associated with Osiris from

the beginning of written records in Egypt9 and described by the

Greek geographer Strabo (who visited Abydos in the first century BC)

as ‘a remarkable structure built of solid stone ... [containing] a

spring which lies at a great depth, so that one descends to it down

vaulted galleries made of monoliths of surpassing size and

workmanship.

There is a canal leading to the place from the great

river ...’10

A few hundred years after Strabo’s visit, when the religion of

Ancient Egypt had been supplanted by the new cult of Christianity,

the silt of the river and the sands of the desert began to drift

into the Osirieon, filling it foot by foot, century by century,

until its upright monoliths and huge lintels were buried and

forgotten.

And so it remained, out of sight and out of mind, until

the beginning of the twentieth century, when the archaeologists

Flinders Petrie and Margaret Murray began excavations. In their 1903

season of digging they uncovered parts of a hall and passageway,

lying in the desert about 200 feet south-west of the Seti I Temple

and built in the recognizable architectural style of the Nineteenth

Dynasty.

However, sandwiched between these remains and the rear of

the Temple, they also found unmistakable signs that ‘a large

underground building’ lay concealed.11

‘This hypogeum’, wrote

Margaret Murray, ‘appears to Professor Petrie to be the place that Strabo mentions, usually called Strabo’s Well.’12

This was good

guesswork on the part of Petrie and Murray. Shortage of cash,

however, meant that their theory of a buried building was not tested

until the digging season of 1912-13. Then, under the direction of

Professor Naville of the Egypt Exploration Fund, a long transverse

chamber was cleared, at the end of which, to the north-east, was

found a massive stone gateway made up of cyclopean blocks of granite

and sandstone.

The next season, 1913-14, Naville and his team returned with 600

local helpers and diligently cleared the whole of the huge

underground building:

What we discovered [Naville wrote] is a gigantic construction of

about 100 feet in length and 60 in width, built with the most

enormous stones that may be seen in Egypt. In the four sides of the

enclosure walls are cells, 17 in number, of the height of a man and

without ornamentation of any kind.

The building itself is divided

into three naves, the middle one being wider than those of the

sides; the division is produced by two colonnades made of huge

granite monoliths supporting architraves of equal size.13

9

See Henry Frankfort, The Cenotaph of Seti I at Abydos, 39th Memoir

of the Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1933, p. 25.

10 The

Geography of Strabo, volume VIII, pp. 111-13.

11

Margaret A. Murray, The Osireion at Abydos, Egyptian Research

Account, ninth year (1903), Bernard Quaritch, London, 1904, p. 2.

12

Ibid.

13 The Times, London, 17 March 1914.

Naville commented with some astonishment on one block he measured in

the corner of the building’s northern nave, a block more than

twenty-five

feet long.14 Equally surprising was the fact that the cells cut into

the enclosure walls had no floors, but turned out, as the

excavations went deeper, to be filled with increasingly moist sand

and earth:

The cells are connected by a narrow ledge between two and three feet

wide; there is a ledge also on the opposite side of the nave, but no

floor at all, and in digging to a depth of 12 feet we reached

infiltrated water. Even below the great gateway there is no floor,

and when there was water in front of it the cells were probably

reached with a small boat.15

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

The most ancient stone building in Egypt

Water, water, everywhere—this seemed to be the theme of the

Osireion, which lay at the bottom of the huge crater Naville and his

men had excavated in 1914. It was positioned some 50 feet below the

level of the floor of the Seti I Temple, almost flush with the

water-table, and was approached by a modern stairway curving down to

the south-east. Having descended this stairway, I passed under the

hulking lintel slabs of the great gateway Naville (and Strabo) had

described and crossed a narrow wooden footbridge—again modern—which

brought me to a large sandstone plinth.

Measuring about 80 feet in length by 40 in width, this plinth was

composed of enormous paving blocks and was entirely surrounded by

water. Two pools, one rectangular and the other square, had been cut

into the plinth along the centre of its long axis and at either end

stairways led down to a depth of about 12 feet below the water

level.

The plinth also supported the two massive colonnades

Naville

mentioned in his report, each of which consisted of five chunky

rose-coloured granite monoliths about eight feet square by 12 feet

high and weighing, on average, around 100 tons.16 The tops of these

huge columns were spanned by granite lintels and there was evidence

that the whole building had once been roofed over with a series of

even larger monolithic slabs.17

16 Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt, p. 391. 17 The Cenotaph of Seti

I at Abydos, p. 18.

Plan of the Osireion.

To get a proper understanding of the structure of the

Osireion, I

found it helpful to raise myself directly above it in my mind’s eye,

so that I could look down on it. This exercise was assisted by the

absence of the original roof which made it easier to envisage the

whole edifice in plan. Also helpful was the fact that water had now

seeped up to fill all of the building’s pools, cells and channels to

a depth of a few inches below the lip of the central plinth, as the

original designers had apparently intended it should.18

Looking down in this manner, it was immediately apparent that the

plinth formed a rectangular island, surrounded on all four sides by

a water-filled moat about 10 feet wide. The moat was contained by an

immense, rectangular enclosure wall, no less than 20 feet thick,19

made of very large blocks of red sandstone disposed in polygonal

jigsaw-puzzle patterns. Into the huge thickness of this wall were

set the 17 cells mentioned in Naville’s report. Six lay to the east,

six to the west, two to the south and three to the north.

Off the

central of the three northern cells lay a long transverse chamber,

roofed with and composed of limestone. A similar transverse chamber,

also of limestone but no longer with an intact roof, lay immediately

south of the great gateway. Finally, the whole structure was

enclosed within an outer wall of limestone, thus completing a

sequence of inter-nested rectangles, i.e., from the outside in,

wall, wall, moat, plinth.

Another notable and outstandingly unusual feature of the

Osireion

was that it was not even approximately aligned to the cardinal

points. Instead, like the Way of the Dead at Teotihuacan in Mexico,

it was oriented to the east of due north. Since Ancient Egypt had

been a civilization that could and normally did achieve precise

alignments for its buildings, it seemed to me improbable that this

apparently skewed orientation was accidental. Moreover, although 50

feet higher, the Seti I Temple was oriented along exactly the same

axis—and again not by accident.

The question was: which was the

older building? Had the axis of the Osireion been predetermined by

the axis of the Temple or vice versa? This, it turned out, was an

issue over which considerable controversy, now long forgotten, had

once raged. In a debate which had many connections with that

surrounding the Sphinx and the Valley Temple at Giza, eminent

archaeologists had initially argued that the Osireion was a building

of truly immense antiquity, a view expressed by Professor Naville in

the London Times of 17 March 1914:

This monument raises several important questions. As to its date,

its great similarity with the Temple of the Sphinx [as the Valley

Temple was then known] shows it to be of the same epoch when

building was made with enormous stones without any ornament. This is

characteristic of the oldest architecture in Egypt. I should even

say that we may call it the most ancient stone building in Egypt.20

18 Ibid., p. 28-9.

19

E. Naville, ‘Excavations at Abydos: The Great Pool and the Tomb of

Osiris’, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, volume I, 1914, p. 160.

20

The Times, London, 17 March 1914.

Reconstruction of the Osireion.

Describing himself as overawed by the ‘grandeur and stern

simplicity’ of the monument’s central hall, with its remarkable

granite monoliths, and by ‘the power of those ancients who could

bring from a distance and move such gigantic blocks’, Naville made a

suggestion concerning the function the Osireion might originally

have been intended to serve:

‘Evidently this huge construction was a

large reservoir where water was stored during the high Nile ... It

is curious that what we may consider as a beginning in architecture

is neither a temple nor a tomb, but a gigantic pool, a waterwork

...21

21 Ibid.

Curious indeed, and well worth investigating further; something

Naville hoped to do the following season. Unfortunately, the First

World War intervened and no archaeology could be undertaken in Egypt

for several years. As a result, it was not until 1925 that the Egypt

Exploration Fund was able to send out another mission, which was led

not by Naville but by a young Egyptologist named Henry Frankfort.

Frankfort’s facts

Later to enjoy great prestige and influence as professor of

Pre-Classical Antiquity at the University of London, Frankfort spent

several consecutive digging seasons re-clearing and thoroughly

excavating the Osireion between 1925 and 1930. During the course of

this work he made discoveries which, so far as he was concerned,

‘settled the date of the building’:

1 - A granite dovetail in position at the top of the southern side of

the

main entrance to the central hall, which was inscribed with the

cartouche of Seti I.

2 - A similar dovetail in position inside the eastern wall of the

central hall.

3 - Astronomical scenes and inscriptions by Seti I carved in relief on

the ceiling of the northern transverse chamber.

4 - The remains of similar scenes in the southern transverse chamber.

5 - An ostracon (piece of broken potsherd) found in the entrance

passage and bearing the legend ‘Seti is serviceable to Osiris’.22

The reader will recall the lemming behaviour which led to a dramatic

change of scholarly opinion about the antiquity of the Sphinx and

the Valley Temple (due to the discovery of a few statues and a

single cartouche which seemed to imply some sort of connection with

Khafre).

Frankfort’s finds at Abydos caused a similar volte-face

over the antiquity of the Osireion. In 1914 it was ‘the most ancient

stone building in Egypt’. By 1933, it had been beamed forward in

time to the reign of Seti I— around 1300 BC—whose cenotaph it was

now believed to be.23

22 The Cenotaph of Seti I at Abydos, pp. 4, 25, 68-80.

23 Ibid., in

general.

Within a decade, the standard Egyptological texts began to print the

attribution to Seti I as though it were a fact, verifiable by

experience or observation. It is not a fact, however, merely

Frankfort’s interpretation of the evidence he had found.

The only facts are that certain inscriptions and decorations left by

Seti appear in an otherwise completely anonymous structure. One

plausible explanation is that the structure must have been built by

Seti, as Frankfort proposed. The other possibility is that the

half-hearted and scanty decorations, cartouches and inscriptions

found by Frankfort could have been placed in the Osireion as part of

a renovation and repair operation undertaken in Seti’s time

(implying that the structure was by then ancient, as Naville and

others had proposed).

What are the merits of these mutually contradictory propositions

which

identify the Osireion as (a) the oldest building in Egypt, and (b) a

relatively late New Kingdom structure?

Proposition (b)—that it is the

cenotaph of Seti I—is the only

attribution accepted by Egyptologists. On close inspection, however,

it rests on the circumstantial evidence of the cartouches and

inscriptions which prove nothing. Indeed part of this evidence

appears to contradict Frankfort’s case. The ostracon bearing the

legend ‘Seti is serviceable to Osiris’ sounds less like praise for

the works of an original builder than praise for a restorer who had

renovated, and perhaps added to, an ancient structure identified

with the First Time god Osiris.

And another awkward little matter

has also been overlooked. The south and north ‘transverse chambers’,

which contain Seti I’s detailed decorations and inscriptions, lie

outside the twenty-foot-thick enclosure wall which so adamantly

defines the huge, undecorated megalithic core of the building. This

had raised the reasonable suspicion in Naville’s mind (though

Frankfort chose to ignore it) that the two chambers concerned were

‘not contemporaneous with the rest of the building’ but had been

added much later during the reign of Seti I, ‘probably when he built

his own temple’.24

To cut a long story short, therefore, everything about proposition

(b) is based in one way or another on Frankfort’s not necessarily

infallible interpretation of various bits and pieces of possibly

intrusive evidence.

Proposition (a)—that the core edifice of

the Osireion had been built

millennia before Seti’s time—rests on the nature of the architecture

itself. As Naville observed, the Osireion’s similarity to the Valley

Temple at Giza ‘showed it to be of the same epoch when building was

made with enormous stones’.

Likewise, until the end of her life,

Margaret Murray remained convinced that the Osireion was not a

cenotaph at all (least of all Seti’s). She said,

It was made for the celebration of the mysteries of Osiris, and so

far is unique among all the surviving buildings of Egypt. It is

clearly early, for the great blocks of which it is built are of the

style of the Old Kingdom; the simplicity of the actual building also

points to it being of that early date. The decoration was added by Seti I, who in that way laid claim to the building, but seeing how

often a Pharaoh claimed the work of his predecessors by putting his

name on it, this fact does not carry much weight. It is the style of

the building, the type of the masonry, the tooling of the stone, and

not the name of a king, which date a building in Egypt.25

This was an admonition Frankfort might well have paid more attention

to, for as he bemusedly observed of his ‘cenotaph’, ‘It has to be

admitted that no similar building is known from the Nineteenth

Dynasty.’26

24 ‘Excavations at Abydos’, pp. 164-5.

25 The Splendour that was

Egypt, pp. 160-1.

26 The Cenotaph of Seti I at Abydos, p. 23.

Indeed it is not just a matter of the Nineteenth Dynasty. Apart from

the Valley Temple and other Cyclopean edifices on the Giza plateau,

no other building remotely resembling the Osireion is known from any

other

epoch of Egypt’s long history. This handful of supposedly Old

Kingdom structures, built out of giant megaliths, seems to belong in

a unique category.

They resemble one another much more than they

resemble any other known style of architecture and in all cases

there are question-marks over their identity.

-

Isn’t this precisely what one would expect of buildings not erected

by any historical pharaoh but dating back to prehistoric times?

-

Doesn’t it make sense of the mysterious way in which the Sphinx and

the Valley Temple, and now the Osireion as well, seem to have become

vaguely connected with the names of particular pharaohs (Khafre and

Seti I), without ever yielding a single piece of evidence that

clearly and unequivocally proves those pharaohs built the structures

concerned?

-

Aren’t the tenuous links much more indicative of the work

of restorers seeking to attach themselves to ancient and venerable

monuments than of the original architects of those monuments—whoever

they might have been and in whatever epoch they might have lived?

Setting sail across seas of sand and time

Before leaving Abydos, there was one other puzzle that I wanted to

remind myself of. It lay buried in the desert, about a kilometer

north-west of the Osireion, across sands littered with the rolling,

cluttered tumuli of ancient graveyards.

Out among these cemeteries, many of which dated back to early

dynastic and pre-dynastic times, the jackal gods Anubis and

Upuaut

had traditionally reigned supreme. Openers of the way, guardians of

the spirits of the dead, I knew that they had played a central role

in the mysteries of Osiris that had been enacted each year at

Abydos— apparently throughout the span of Ancient Egyptian history.

It seemed to me that there was a sense in which they guarded the

mysteries still. For what was the Osireion if was not a huge,

unsolved mystery that deserved closer scrutiny than it has received

from the scholars whose job it is to look into these matters? And

what was the burial in the desert of twelve high-prowed, seagoing

ships if not also a mystery that cried out, loudly, for solution?

It was the burial place of those ships I was now crossing the

cemeteries of the jackal gods to see:

The Guardian, London, 21

December 1991:

A fleet of 5000-year-old royal ships has been found

buried eight miles from the Nile. American and Egyptian

archaeologists discovered the 12 large wooden boats at Abydos ...

Experts said the boats—which are 50 to 60 feet long—are about 5000

years old, making them Egypt’s earliest royal ships and among the

earliest boats found anywhere ...

The experts say the ships,

discovered in September, were probably meant for burial so the souls

of the pharaohs could be transported on them. ‘We never expected to

find such a fleet, especially so far from the Nile,’ said David

O’Connor, the expedition leader and curator of the Egyptian Section

of the University Museum of

the University of Pennsylvania ...27

The boats were buried in the shadow of a gigantic mud-brick

enclosure, thought to have been the mortuary temple of a Second

Dynasty pharaoh named Khasekhemwy, who had ruled Egypt in the

twenty-seventh century BC.28

O’Connor, however, was certain that

they were not associated directly with Khasekhemwy but rather with

the nearby (and largely ruined) ‘funerary-cult enclosure built for

Pharaoh Djer early in Dynasty I. The boat graves are not likely to

be earlier than this and may in fact have been built for Djer, but

this remains to be proven.’29

A sudden strong gust of wind blew across the desert, scattering

sheets of sand. I took refuge for a while in the lee of the looming

walls of the Khasekhemwy enclosure, close to the point where the

University of Pennsylvania archaeologists had, for legitimate

security reasons, reburied the twelve mysterious boats they had

stumbled on in 1991. They had hoped to return in 1992 to continue

the excavations, but there had been various hitches and, in 1993,

the dig was still being postponed.

In the course of my research O’Connor had sent me the official

report of the 1991 season,30 mentioning in passing that some of the

boats might have been as much as 72 feet in length.31

He also noted

that the boat-shaped brick graves in which they were enclosed, which

would have risen well above the level of the surrounding desert in

early dynastic times, must have produced quite an extraordinary

effect when they were new:

Each grave had originally been thickly coated with mud plaster and

whitewash so the impression would have been of twelve (or more) huge

‘boats’ moored out in the desert, gleaming brilliantly in the

Egyptian sun. The notion of their being moored was taken so

seriously that an irregularly shaped small boulder was found placed

near the ‘prow’ or ‘stern’ of several boat graves. These boulders

could not have been there naturally or by accident; their placement

seems deliberate, not random. We can think of them as ‘anchors’

intended to help ‘moor’ the boats.32

Like the 140-foot ocean-going vessel found buried beside the Great

Pyramid at Giza (see Chapter Thirty-three), one thing was

immediately clear about the Abydos boats—they were of an advanced

design capable of riding out the most powerful waves and the worst

weather of the open seas.

According to Cheryl Haldane, a nautical

archaeologist at Texas A-and-M University, they showed ‘a high

degree of technology combined with grace’.33

27 Guardian, London, 21 December 1991.

28

David O’Connor, ‘Boat Graves and Pyramid Origins’, in Expedition,

volume 33, No. 3, 1991, p. 7ff.

29 Ibid., pp. 9-10.

30 Sent to me by

fax 27 January 1993.

31 David O’Connor, ‘Boat Graves and Pyramid

Origins’, p. 12.

32 Ibid., p. 11-12.

33 Guardian, 21 December 1991.

Exactly as was the case

with the Pyramid boat, therefore (but at least 500 years earlier)

the Abydos fleet seemed to indicate that a people able to draw upon

the accumulated experiences of a long tradition

of seafaring had been present in Egypt from the very beginning of

its 3000 year history.

Moreover I knew that the earliest wall

paintings found in the Nile Valley, dating back perhaps as much as

1500 years before the burial of the Abydos fleet (to around 4500 BC)

showed the same long, sleek, high-prowed vessels in action.34

Could an experienced race of ancient seafarers have become involved

with the indigenous inhabitants of the Nile Valley at some

indeterminate period before the official beginning of history at

around 3000 BC? Wouldn’t this explain Egypt’s curious and

paradoxical—but nonetheless enduring—obsession with ships in the

desert (and references to what sounded like sophisticated ships in

the Pyramid Texts, including one said to have been more than 2000

feet long)?35

34 See Cairo Museum, Gallery 54, wall-painting of ships from Badarian period c. 4500 BC.

35

The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, p. 192, Utt. 519: ‘O Morning

Star, Horus of the Netherworld ... you having a soul and appearing

in front of your boat of 770 cubits ... Take me with you in the

cabin of your boat.’

In raising these conjectures, I did not doubt that religious

symbolism had existed in Ancient Egypt in which, as scholars

endlessly pointed out, ships had been designated as vessels for the

pharaoh’s soul. Nevertheless that symbolism did not solve the

problem posed by the high level of technological achievement of the

buried ships; such evolved and sophisticated designs called for a

long period of development.

Wasn’t it worth looking into the

possibility—even if only to rule it out—that the Giza and Abydos

vessels could have been parts of a cultural legacy, not of a

land-loving, riverside-dwelling, agricultural people like the

indigenous Ancient Egyptians but of an advanced seafaring nation?

Such seafarers could have been expected to be navigators who would

have known how to set a course by the stars and who would perhaps

also have developed the skills necessary to draw up accurate maps

and charts of the oceans they had traversed.

Might they also have been architects and stonemasons whose

characteristic medium had been polygonal, megalithic blocks like

those of the Valley Temple and the Osireion?

And might they have been associated in some way with the legendary

gods of the First Time, said to have brought to Egypt not only

civilization and astronomy and architecture, and the knowledge of

mathematics and writing, but a host of other useful skills and

gifts, by far the most notable and the most significant of which had

been the gift of agriculture?

There is evidence of an astonishingly early period of agricultural

advance and experimentation in the Nile Valley at about the end of

the last Ice Age in the northern hemisphere. The characteristics of

this great

Egyptian ‘leap forward’ suggest that it could only have resulted

from an influx of new ideas from some as yet unidentified source.

Back to

Contents

or

Continue to Chapter 46

→

|