|

from

AncientEgypt Website

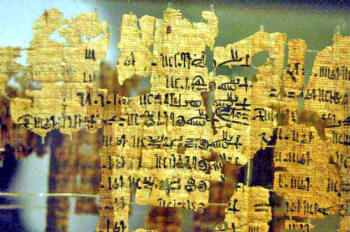

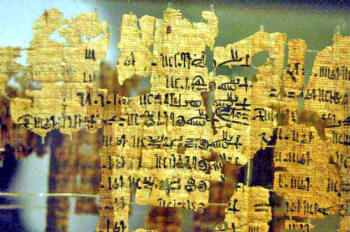

The Turin Kinglist, also known as

the Turin Royal Canon, is a unique papyrus, written in

hieratic, currently in the Egyptian Museum at Turin, to which it

owes its modern name.

It is broken into over 160 often very small fragments, many of which

have been lost. When it was discovered in the Theban necropolis by

the Italian traveller Bernardino Drovetti in 1822, it seems

to have been largely intact, but by the time it became part of the

collection of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, its condition had

severely deteriorated.

Turin Kinglist

The importance of this papyrus was first recognized by the French

Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion, who, later followed

by Gustavus Seyffarth took up its reconstruction and

restoration. Although they succeeded in placing most of the

fragments in the correct order, the diligent intervention of these

two men came too late and many lacunae to thus important papyrus

still remain.

Written during the long reign of Ramesses II, the papyrus, now

estimated at 1.7m long and 0.41m high, comprises on the recto an

unknown number of pages that hold a list of names of persons and

institutions, along with what appears to be the tax-assessment of

each.

It is, however, the verso of the papyrus that has attracted the most

attention, as it contains a list of gods, demi-gods,

spirits,

mythical and human kings who ruled Egypt from the beginning of time

presumably until the composition of this valuable document.

The beginning and ending of the list are now lost, which means that

we are missing both the introduction of the list - if ever there was

such an introduction - and the enumeration of the kings following the

17th Dynasty. We therefore do not know for certain when after the

composition of the tax-list on the recto an unknown scribe used the

verso to write down this list of kings. This may have occurred

during the reign of Ramesses II, but a date as late as the 20th

Dynasty can not be excluded. The fact that the list was scribbled on

the back of an older papyrus has been seen by some as an indication

that it was of no great importance to the writer. Perhaps it was a

text that needed to be copied in a scribes' school by way of

exercise?

We are also left in the dark as to what source or sources our

laborious scribe used to write down the list.

-

Did he simply copy an

already existing papyrus?

-

And if so, for what reason?

-

And what has

happened to the original?

-

How was that compiled?

-

Or did the scribe,

probably having access to the archives of the temples, compile the

list himself, using ancient tax-notes, decrees and documents?

The

latter possibility seems the less likely and would infer that the

Turin Kinglist is indeed a unique document.

There are several other lists that enumerate the predecessors of a

king, such as the lists in the temples of Seti I and Ramesses II at

Abydos -to name but two-, so what makes the Turin Kinglist so

exceptional? The other lists, although very valuable for the study

of Ancient Egyptian chronology as well, are nothing more than an

enumeration of some of the "ancestors" of the current king.

Often the current king, or one of his

contemporaries, is seen in adoration before the cartouches or

representations of the king’s "ancestors". The current king is in

fact represented as the good heir who pays respect to his long line

of "ancestors". The word "ancestor" can not be taken literally, as

the current king was in no way a descendant of most of his

predecessors. Such lists had a more cultic and political reason for

being, for indeed they confirmed that the current king was the

rightful heir of the kings that had ruled Egypt for many centuries.

These cultic lists are more a subjective

choice of predecessors than an actual enumeration of all kings: they

will in most cases include kings such as Menes and Mentuhotep II,

for they have played a pivotal role in the history of Ancient Egypt.

Other, less important kings, usurpers or kings that were considered

to be illegitimate, such as the kings connected to the Amarna-revolution,

were omitted from the lists.

The Turin Kinglist, on the other hand, does a lot more than

simply list some kings: it groups them together and it mentions the

duration of their reigns. What’s more, it even takes note of some

kings that are omitted from the cultic lists, such as the otherwise

quite unpopular Hyksos! Despite the fact that it begins with an

enumeration of gods, demi-gods, spirits and mythical that were

supposed to have ruled Egypt before the reign of Menes, it was not a

cultic list and it does not serve the purpose of showing the current

king as the good heir to his "ancestors".

The king list of the Turin Kinglist was originally divided

over an unknown number of columns or sheets, of which only 11

remain. Columns I to V comprised 25 or 26 lines of text, column VI

at least 27 and columns IX and X at least 30. The increasing number

of lines as the Canon reaches its end seems to indicate that the

scribe realized that he would not have sufficient space on his

papyrus to write down all the royal names known to him in 25- or

26-line columns.

Most lines give the name of a particular king, written in a

cartouche, followed by the number of years he ruled, and in some

cases even by the number of months and days. The number of years

credited to some kings of the 1st and 2nd Dynasty is so high, that,

in those particular cases, they are most likely not correct. It has

sometimes been postulated that this high number of years does not

reflect the length of a reign but the age at which the king died.

Although this possibility can not

entirely be overruled, it is strange that the writer should choose

to note the age of a king in one case and the length of his reign in

another. I would rather suspect that the scribe mistook the

year-labels of early kings as representations of different years,

whereas it is likely that several labels actually referred to the

same year..

For the kings of the first three dynasties, a name is written in a

cartouche as well, despite the fact that cartouche-names were not

used prior to the rule of the last king of the 3rd Dynasty, Huni.

The cartouche-name used for these kings is often similar to the

names used for the same kings in the cultic king-lists, but they are

quite different from the Horus-name by which they were known

officially during their reign.

The relationship between the Horus-names

of these early kings and the names used in the Turin Kinglist is not

certain: for the later 1st Dynasty kings, the name in the kinglists

seems to be based on their Nebti-name, but how the earlier kings of

the 1st Dynasty and all kings of the 2nd and 3rd Dynasties got their

names is not known.

The kings are grouped together logically based on the city where

they took up residence. These groups do not (entirely) correspond to

the dynasties into which the kings were placed by Manetho. This

indicates that the notion of dynasties was not present or fully

developed before the 19th or 20th Dynasty.

Most groups comprise a line of summation that totals the number of

years that this particular group has ruled. These summations are

sometimes written on 1 line, sometimes divided over 2 lines and

sometimes written in 1 line that is so long that it encroaches the

next column. In some cases a group is introduced by a heading. The

fact that there are far less headings than summations may rather be

the result of the fragmentary state of the Canon than an

inconsistency on the part of the scribe who wrote or copied the

list.

Despite its incomplete and fragmentary nature, and despite the fact

that the placing of the fragments has been contested from time to

time, the Turin Kinglist is one of our most important sources of

knowledge about the chronology of Egypt between the 1st and 17th

Dynasty.

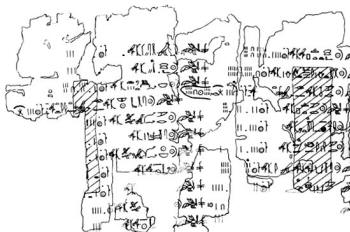

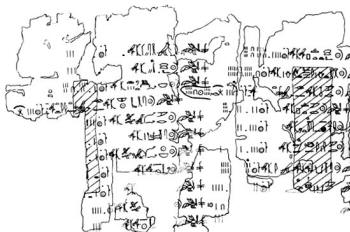

The following pages contain a hieroglyphic transcription of that

part of the Turin Kinglist that lists actual kings. The

transcription has been based on the publication of the Turin Kinglist by

Alan H. Gardiner. Although a rather old publication (the

first edition is dated to the late 50's), the placement of the

different fragments as proposed by Gardiner is still largely

accepted by most Egyptologists. Since his publication, other

fragments seem to have been placed as well. This will not yet be

reflected in my current transcription of the Canon.

When making this hieroglyphic transcription, I have tried to respect

the disposition of the signs as much as possible, except that I have

oriented the signs from left to right for practical reasons, instead

of from right to left as they were written in the original hieratic

text.

The translations are written in italics and are my own. Words in the

translation that are written in red were written in red ink in the

original text as well. Translations between [ ] are restorations of

smaller lacunae. Where a restoration of a lacuna was not possible or

uncertain, the signs /// will appear.

If the need arises to make some additional remarks about a

particular line of text, this will be done using a smaller font.

A total of 16 "groups" can be distinguished (clicking on the links

below will take you to a hieroglyphic transcription and a

translation of that particular group):

Contents

-

I,x - I,21: Ptah and the

Great Ennead

-

I,22 - II,3 : Horus and the

Lesser Ennead (?)

-

II,4 - II,8 : the spirits

-

II,9 : a mythical group of

kings

-

II,10 : another group of

mythical kings (?)

-

II,11 - III,26/27: 1st to

5th Dynasty

-

IV,1 - IV,14/15: 6th to 8th

(?) Dynasty

-

IV,15/17: 1st to 6th (or

8th ?) Dynasty

-

IV,18 - V,10: 9th and 10th

Dynasty

-

V,11 - V,18: 11th Dynasty

-

V,19 - VI,3: 12th Dynasty

-

VI,4 - X,12/13: 13th and

14th Dynasty

-

X,14 - X,21: 15th Dynasty (Hyksos)

-

X,22, X,30 (?): a group of

non-identified kings

-

XI,1 (?) - XI,15: a group

of probably Theban kings contemporary with the Hyksos

(17th Dynasty ?)

-

unplaced fragments

|