|

by Philip Coppens This article first appeared in Frontier Magazine 8.3 (May 2002) and has been slightly adapted. from PhilipCoppens Website

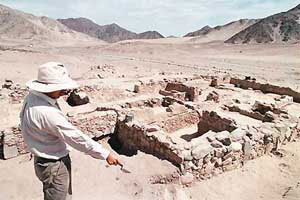

Even though they were discovered in 1905, they were quickly forgotten as the site rendered no gold or even ceramics. Ruth Shady has been excavating in Caral since 1994. She is a member of the Archaeological Museum of the National University of San Marcos in Lima. Since 1996, she has co-operated with Jonathan Haas, of the American Field Museum. She felt that the “pyramids” were just that: before, they were considered to be natural hills. Her research led to the announcement of the carbon dating of the site, in the magazine Science on April 27, 2001.

What is Caral like? The site is in fact so old that it predates the ceramic period. Its importance resides in its domestication of plants, including cotton, beans, squashes and guava. The absence of ceramics meant that these foods could not be cooked – though roasting was an option.

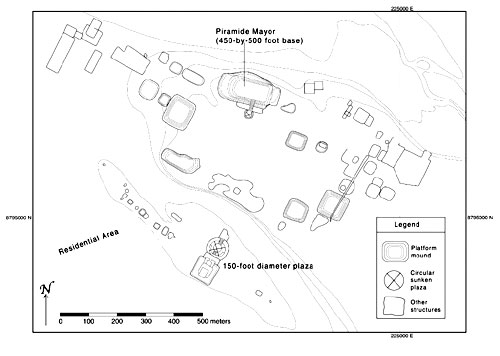

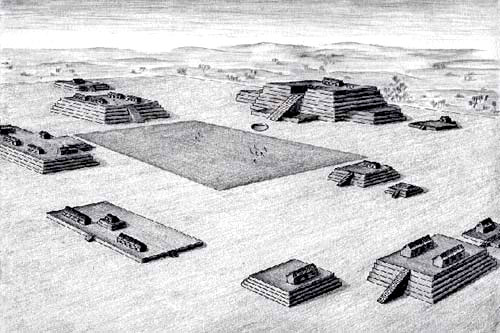

The heart of the site covers 150 acres and contains six stone platform mounds – pyramids. The largest mound measures 154 by 138 m, though it rises only to an altitude of twenty meters; two sunken plazas are at the base of the mound and a large plaza connects all the mounds. The largest pyramid of Peru was terraced with a staircase leading up to an atrium-like platform, culminating in a flattened top housing enclosed rooms and a ceremonial fire pit.

All pyramids were built in one or two phases, which means that there was a definitive plan in erecting these monuments. The design of the central plaza would also later be incorporated in all similar structures across the Andes in the millennia to come – thus showing that Caral was a true cradle of civilization.

But apart from an economic model of exchange, the new social model also meant that a labor force existed that had in essence little to do. This labor force could thus be used for “religious purposes”. Caral might have been the natural result of this process – just like the pyramids of Egypt seem to have been the result of an available workforce.

(Courtesy of Field

Museum)

For an unknown reason, Caral was abandoned rapidly after a period of 500 years (ca. 2100 BC). The preferred theory as to why the people migrated is that the region was hit by a drought, forcing the inhabitants to go elsewhere in search of fertile plains. The harsh living conditions have since not disappeared. According to the World Monuments Fund (WMF), Caral is one of the 100 important sites under extreme danger. Shady argues that if the existing pyramids are not reinforced, they will disintegrate further. The environmental conditions are such so extreme that this will not be an easy task. The task is further complicated by the fact that thieves roam the area, in search of archaeological treasures.

Though the Peruvian government has given half a million dollars in aide, Shady argues it is not sufficient – and the WMF even argues that the Peruvian government is a contributing factor to the site’s decay. Private donators have stepped in to help, such as Telefonica del Peru.

But Shady is

hopeful that the main source of income will be tourism, who for a

long period were shunned from the site as they might inhibit

archaeological excavations. The hope is that the site will soon

become part of the tourist route, taking in the enigmatic Nazca

lines and the infamous Machu Picchu. Though much less famous than

those two sites – it is much older and offers the traveler the

possibility to see pyramids – in South America.

|

22

km inland from Puerto Supe, along the desert coast, 120 km north of

the Peruvian capital Lima, archaeologists proved that even in modern

times, major discoveries can still be made. The ancient pyramids of Caral (click image right) predate the

Inca civilization by 4000 years, but were flourishing a century

before the pyramids of Gizeh… They have been identified as the most

important archaeological discovery since the discovery of Machu

Picchu in 1911.

22

km inland from Puerto Supe, along the desert coast, 120 km north of

the Peruvian capital Lima, archaeologists proved that even in modern

times, major discoveries can still be made. The ancient pyramids of Caral (click image right) predate the

Inca civilization by 4000 years, but were flourishing a century

before the pyramids of Gizeh… They have been identified as the most

important archaeological discovery since the discovery of Machu

Picchu in 1911.

How

did the culture begin? Before Caral, there is no evidence except the

existence of several small villages. It is suggested that these

merged in 2700 BC, quite possibly based on the success of early

agricultural cultivation and fishing techniques. The invention of

cotton fishing nets must have greatly facilitated the fishing

industry. It is believed that this excess of food might have

resulted in trade with the religious centers.

How

did the culture begin? Before Caral, there is no evidence except the

existence of several small villages. It is suggested that these

merged in 2700 BC, quite possibly based on the success of early

agricultural cultivation and fishing techniques. The invention of

cotton fishing nets must have greatly facilitated the fishing

industry. It is believed that this excess of food might have

resulted in trade with the religious centers.