|

by Philip Coppens

This article originally appeared in

Frontier 1.2 (1995) and has been

adapted

from

PhilipCoppens Website

|

The “megalithic

civilization” in Western Europe is still a

civilization that is ill-understood, if only because it

has suffered from decades of scientific neglect. At

present, some of the answers about the monuments they

left behind is becoming clearer, but questions remain as

to who this civilization was, and what became of them.

.

Philip

Coppens |

The megalithic civilization has only in

recent years become the subject of serious scientific investigation.

Previously, it seems that most archaeologists preferred the warmer

climates of Egypt and the Middle East to identify our forefather’s

past. After all, was that area not the cradle of civilization?

In retrospect, the answer suggests it is not, for once the

megalithic monuments were subjected to dating, some were found to be

much older than their counterparts in Egypt.

Some of the problem between megalithic Western Europe and the

civilizations of the Middle East is a question of prior interest. We

have the Bible, the pyramids and tales of the ancient Gods. Europe

only seems to have Stonehenge. Europe has stories of how the Romans

came and conquered the local population, leaving a less than

impressive accounts of what for a long time were believed to be the

megalith builders. It once again took well into the 20th century

before it was realized that the megalith builders were as far

removed from the Romans as we are… and the earliest megalithic

builders more than twice that amount of years, predating the

construction of the pyramids.

This picture also threw the entire debate of what came first on its

head. Civilization was thought to have spread from the Middle East.

But redating of the megalithic monuments indicated that it could

have been the other way around – even though no-one has ever

suggested this. There are various reasons for this. When in the

early 20th century it was suggested that the Egyptian civilization

was created by “white men”, this was seen as either evidence of the

foolish theory of Atlantis, or of racism on the part of the person

expressing that opinion. Though there is nothing to indicate that

“white men” did indeed create Egypt, the intriguing conclusion of

the available evidence is that they could have been. Furthermore,

“megalithic Europe” communicated with each other via the shores,

using boats.

Barry Cunliffe has labeled it “Facing

the Ocean”, as most of the people traveled along the Atlantic shores

of Western Europe, reaching from the Orkneys in the North, to

Morocco in the South. Thus, they had the boats to enter the

Mediterranean Sea and “seed” civilization there. Whether the

enigmatic megalithic

structures of Malta should therefore be seen as

an influence from the west or the east is a good question – and the

most likely answer might be that it was influenced from both sides,

resulting in the unique structures the megalithic temples of the

island have.

Despite making progress, little is still known about “the megalithic

civilization”. Megalithic literally means “large stones”, and thus

the civilization is identified by the legacy they left… and which in

Western Europe was often the subject of violent destructions in the

16th till 19th century, when terrain with megalithic remains were

often reclaimed for agricultural purposes.

The destruction or burial of stones, including those at Avebury,

makes the search for purpose and interpretation of the sites more

and more difficult.

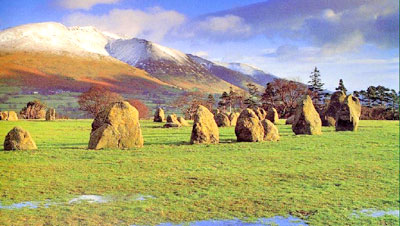

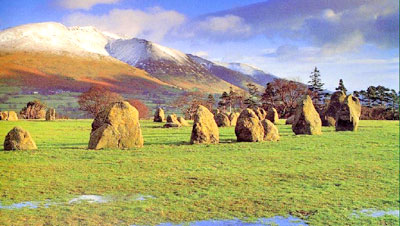

Today, megaliths seem to have survived

more in desolate locations – unless they are of the magnitude of

Stonehenge and Avebury, which were outside of all proportions that

the largest stones remained intact. But finding megaliths on the

slopes of mountains in the Lake District and not in the centre of

London should not lead one to conclude that megaliths were built in

inaccessible locations; more that those in the centre of London were

probably raised to the ground by Roman if not earlier times.

Major inroads into the megalithic civilization were created by

Gerald Hawkins and Alexander Thom. Hawkins stated that Stonehenge

clearly displayed astronomical knowledge and hence concluded it was

a calendar. Archaeologists disagree with the calendar, but do agree

that the alignments of Stonehenge are there because the builders had

specific ritual festivities at the main events of the sun: the

equinoxes and the solstices.

Thom concluded that many of the lesser

known monuments also had stellar alignments; and his research

occurred largely in Brittany, thus showing that the astronomical

component of the megalithic structures seemed at the core of the

building of the monuments itself. Since then, this possibility has

been confirmed in almost all megalithic remains, as far as Egypt.

Still, when their theories were originally aired, Thom and Hawkins

were largely treated as parias in the scientific community. Thom concluded that many of the lesser

known monuments also had stellar alignments; and his research

occurred largely in Brittany, thus showing that the astronomical

component of the megalithic structures seemed at the core of the

building of the monuments itself. Since then, this possibility has

been confirmed in almost all megalithic remains, as far as Egypt.

Still, when their theories were originally aired, Thom and Hawkins

were largely treated as parias in the scientific community.

Thom and Hawkins were breaking the

barrier that the megalithic civilization was indeed worthy of

scientific study. Furthermore, they began to push the boundaries,

making it older than Egypt and the rest of the Middle East. That did

not go down well, and it was even more bizarre that one researcher

who followed in their steps, Martin Brennan was not allowed to enter

Ireland after he had climbed a fence to photograph a sunrise from a

megalithic monument.

Much less known, yet equally impressive, is the 20 year long study

performed by Aubrey Burl, who finished his overview of hundreds if

not thousands of megalithic monuments in Europe in the mid 1990s.

His conclusion read that the first crude stone structures were

created in the Lake District, north-western England. From there,

they spread South, towards Wessex, Devon and Cornwall. From there,

they reached south-western Ireland. Northern Ireland was “seeded”

directly from the Lake District, as it was a short stretch of water

that separated the two locations. As to their purpose, Burl was very

careful, but did suggest that he felt they had a religious purpose,

though a dual purpose, such as meeting place for tribes or between

tribes, was most likely a secondary purpose of the sites.

An important clue is that even though Brittany is well-known for its

tremendous concentration of megalithic monuments, it is in the far

less known region east of Paris, around the city of Sens, that the

largest concentration can be found. As the area is largely urban and

industrial and not a holiday destination like Brittany, few people

are however aware of this fact. One person who did become intrigued

by these stones was the Belgian historian Marcel Mestdagh.

His area of expertise were the Viking

invasions. He noted that the invasion pattern in western Europe

seemed to follow a particular feature of the landscape that other

researchers had been unable to identify. Mestdagh believed that this

pattern had to do with the distribution of megaliths across the

landscape. Furthermore, he noted that this pattern seemed to focus

in on Sens, which was unique from a Viking perspective in the sense

that the town was besieged, rather than sacked as all other towns.

Aware that megaliths were often used by later people as border

stones, Mestdagh wondered whether they might actually be markers

along the roads.

Since then, other researchers have come

to the conclusion that many megalithic monuments were indeed

situated along ancient roads. If the megaliths marked roads – and

noting that the Vikings found a Europe that was largely rural, not

urbanized, could it be that they followed this system, eventually

ending up in Sens? If so, then it meant that all roads seemed to

lead to Sens – which made sense, as, having the largest

concentration of megaliths, it might thus be the capital.

Furthermore, Sens was close to Paris, which in later years would

become the capital of France.

Where did the megalithic builders come from, and more importantly,

where did they go to? Whereas the local European population at the

time might have decided to just start erecting large stone

monuments, the question is why they stopped – and whether they

abandoned the regions they formerly inhabited. And if so, why?

As they left no written sources, identifying these people by their

language is impossible. Thomas O’Rahilly researched early Irish

history and came across an ancient language that had words that were

Indo-European. One of these dialects was the Hiberno-Brittany

dialect, known as Ernbelre, the language of the Erainn. In

The

Secret Languages of Ireland, R.A. Stewart MacAlister noted how he

came across a group of people in Liverpool, a group largely on the

outskirts of society. They still spoke Ernbelre, in the beginning of

the 20th century. He concluded that the megalithic people were still

alive at the time of the Roman conquest. They were known as Ateconti

(Aithech Tuatha, “for rent”), as they were used in the Roman

legions. Later, the Irish would consider them to be lowest of all

social classes.

MacAlister noted that the group still lived as if they were a clan,

marrying inside the clan, behaving in mysterious ways about their

language, etc.

Though their descendents may thus have lived onwards in Western

Europe, what made them stop building with “large stones”? The

megalithic civilization in Europe ended in ca. 1200 BC, roughly the

time when Stonehenge was no longer extended. It times the end, but

does not identify the cause.

Perhaps foreign invaders came into Western Europe. Another option

might be that the end of the megalithic civilization coincided with

the onset of a Dark Age in Europe. It would last approx. half a

millennium, when the Greek and Roman civilizations began to

flourish. The onset of the Dark Age is also linked with the end of

the Cretan civilization, which itself was linked to the eruption of

the Santorini volcano.

Might the massive eruption of this volcano

have destroyed the Western economy? As both Crete and the Megalithic

civilization were strongly relying on the sea as a means of

communication, this may be the real cause for the end of the

megalithic era: the downturn in the European economy meant that

there was no more time or resource for a continued expansion of

megalithic monuments, such as Stonehenge.

However, the end of the civilization remains largely shrouded in

mystery – and might remain for a while longer.

|

Thom concluded that many of the lesser

known monuments also had stellar alignments; and his research

occurred largely in Brittany, thus showing that the astronomical

component of the megalithic structures seemed at the core of the

building of the monuments itself. Since then, this possibility has

been confirmed in almost all megalithic remains, as far as Egypt.

Still, when their theories were originally aired, Thom and Hawkins

were largely treated as parias in the scientific community.

Thom concluded that many of the lesser

known monuments also had stellar alignments; and his research

occurred largely in Brittany, thus showing that the astronomical

component of the megalithic structures seemed at the core of the

building of the monuments itself. Since then, this possibility has

been confirmed in almost all megalithic remains, as far as Egypt.

Still, when their theories were originally aired, Thom and Hawkins

were largely treated as parias in the scientific community.