|

by David Talbott

from

Thunderbolts Website

May 16, 2005

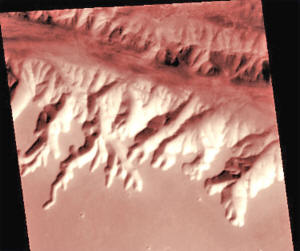

Upper credit:

NASA/JPL/Arizona State

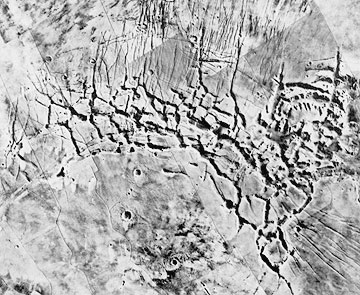

Lower Credit: ESA

The greatest canyon in

the solar system, Valles Marineris on Mars, underscores the contrast

between two interpretations of the planet’s history. Now,

high-resolution images of the chasm cast new doubts on old

explanations.

In recent years, no planet (apart from Earth) has received more

scrutiny than our neighbor Mars. The “planet of a thousand

mysteries” is more than an unusual member of the solar system. It

has emerged as a laboratory in space for the exploration of solar

system history. And the story it has to tell is so different from

the things we learned in school that a retreat from all prior

doctrines is now essential. Current geologic concepts, based on

terrestrial observations of volcanism, erosion, and shifting

surfaces, fail to account for the features of Mars, and the history

and geology of Mars that have been built on those concepts is

incomprehensible. But letting go of a cherished belief system often

requires a shock.

Fittingly, it is the electrical viewpoint that provides the required

“shock to the system”. The contributors to this page believe that on

the objective test of “predictive ability”—the only legitimate test

in the theoretical sciences—the electrical hypothesis will account

for the dominant features on Mars, where popular theory fails.

Often the simplest test of a new approach is to consider its most

extraordinary claim. Of all the enigmatic features on Mars, none is

more striking than Valles Marineris, the great trench cutting across

more than 3000 miles of the Martian surface. In our Picture of the

Day for April 08, 2005 “The Thunderbolt that Changed the Face of

Mars”, we suggested that Valles Marineris was created within minutes

or hours,

"by a giant electric arc sweeping across the surface of

Mars. Rock and soil were lifted into space and some fell back to

create the great, strewn fields of boulders first seen by the Viking

and Pathfinder landers”.

But what will it take for planetary scientists to consider a new way

of seeing Valles Marineris? It will require a willingness to

reconsider all assumptions, without prejudice. A prejudice is an

unfounded assumption that leaves one in a state of partial

blindness. On the matter of Martian history in general, and Valles

Marineris in particular, the most powerful prejudice is an untested

supposition, the bane of space age science: the idea that planets

have moved on their present courses for billions of years. No one

should have the intellectual privilege of asserting such an idea as

dogma. The idea originated as a guess and then, in the absence of

any definitive evidence, crystallized into a doctrine held in place

only by the inertia of belief.

The second requirement is to allow for the possibility that the Sun

and planets are charged bodies so that, within an unstable solar

system, electrical arcing between these bodies may have been the

dominant force that carved surface features. Yes, this is an

extraordinary possibility, but it is also supported by an immense

library of evidence, as we intend to show in these Pictures of the

Day.

Forces external to the planet Mars have shaped its past far more

dramatically than any process in the toolkit of standard geology.

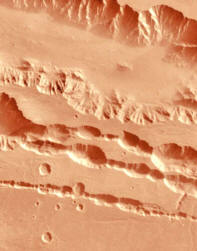

Look at the Valles Mariners as pictured above. The continental-scale

chasm lies on a bulge rising 11 km (6.8 mi) above the surrounding

plains. Did evolution of the planet in isolation produce this vast

bulge? And what of the trench itself? Traditional geology cannot

explain in a plausible way Valles Marineris! Here, for example, is

the “explanation” offered in a recent release by the European Space

Agency:

“The whole canyon system itself is the result of a variety of

geological processes. Probably tectonic rifting, water and wind

action, volcanism and glacial activity all have played major roles

in its formation and evolution.”

The anomalies and exceptions to

this litany of standard geologic processes reduce the applicability

of standard theory to the point of leaving nothing that it explains.

In the electric view, the electric force raised the Tharsis bulge,

along with the surface “blisters” of Olympus Mons and its companions

to the west, and a planetary-sized electric arc cut Valles Marineris

into the bulge.

Today all but a tiny minority of geologists have dropped the idea of

creation by flooding. The most common agent currently cited is

surface spreading. But higher resolution pictures lend no credence

to this concept as well, and many high-resolution views appear to

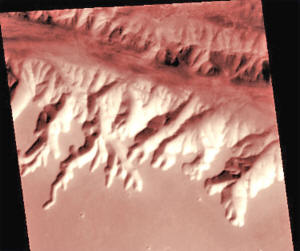

categorically refute it. To illustrate the point we offer a close-up

view (lower image) of a small section of the western end of the

canyons of Valles Marineris—Tithonium Chasma and Ius Chasma (marked

by the white box in the context picture above). The second (lower)

picture, with a resolution of 52 meters per pixel, shows the neatly

“machined” look predicted by the electrical arcing hypothesis.

This is certainly not the appearance predicted by the popular idea

of a massive “rift” opening up on the Martian surface.

There is no evidence of lateral surface movement, and the stubby,

cleanly cut alcoves stand as clear witnesses to the removal of

material, as if by a router bit. So too, the sharply defined chain

of overlapping craters in the upper right speaks for the scooping

out and removal of material, not for rifting. Of this pattern,

predictable under the electric hypothesis, the Valles Marineris

provides many instances.

We have placed two examples

in below images:

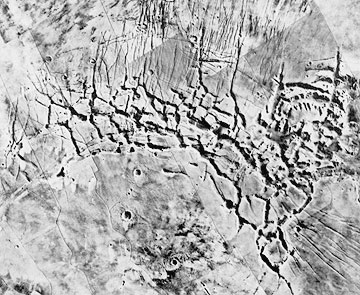

For a time, the most plausible instance of surface spreading was

Labyrinthus Noctis, the chaotic region to the west (left) in the

upper top picture. In particular, that explanation seemed plausible in

the earlier Mariner probe image seen below.

Some scientists had

compared this region to the cracked surface of a loaf of bread as

the surface is raised and spread during baking.

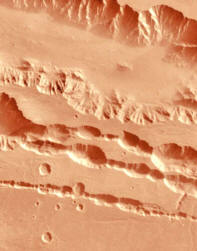

But more recent pictures show something quite different.

Above we see

the same indications of cleanly cut trenches or channels now

revealed throughout Valles Marineris, though the pattern is more

chaotic and the depressions more shallow. From an electric

viewpoint, the stupendous arc that cut Valles Marineris was diffused

into secondary filaments before being quenched. As seen in numerous

counterparts on Mars, the depressions of Labyrinthus Noctis appear

as complexes of crater chains and flat valleys, cut by the same

force that created the overlapping craters elsewhere on Mars.

The

surface areas untouched by the arc thus remain as buttes and

surrounding plains above scalloped cliffs. The smooth surfaces above

the valleys show no evidence of rifting or of the supposed stressed

that are claimed to have "torn" the surface, just a complex of even

more shallow, flat-bottomed and often parallel grooves, a recognized

signature of electric arcing.

|