|

Study 3: Avian

formation on a South-facing slope along the Northwest rim of the

Argyre Basin

by:

Wilmer C. Faust

Keith Laney

William R. Saunders

George J. Haas

James S. Miller

Contributing DVMs:

Doctor A. J. Cole

Doctor Joseph M. Friedlander

CONTENTS

Back to Contents

Abstract – James S. Miller

This is a description of a feature that rests against a web of

structural components found on a mound within the Argyre Basin of

Mars in Mars Global Surveyor image M1402185 (Figure1

below). There are

defining aspects of this feature, which when taken together induce

the visual impression of an avian formation. Adjoining this

formation is a composite of cellular features that form a

compartmentalized infrastructure. The topography and the geology of

the formation is examined and compared to a random example of

circular mounds and sediment ponds found in the Dao Vallis Region.

A list of other sites is provided that

is similar in nature but do not produce a similar feature. Two

veterinarians provide a critical analysis of the avian features and

an independent geo-scientist provides an analysis of the

topographical mechanisms required to shape these features. Finally

an overview of the topography is given.

This analysis will indicate that there are too many avian features

present in this formation to suggest that it was the result of

random forces. Natural forces in the area are seasonal and have

occurred over the millennium. In only 6 years of natural weathering

occurring in the same sequence the odds of an isolated effect would

be 1 in 46,656. Otherwise, it is 1 in 36 if it occurs only once.

The

basic underlying question is; what are the chances of seasonal

effects occurring only once? In other words, the avian formation

appears to have permanence. No possible combinations of natural

influences on the landscape could have altered the image without

erasing some part of the feature. The overall impression of this

feature as opposed to those, which are found naturally occurring, is

that this approaches a work of art in its completeness. A

terrestrial comparison is also offered, suggesting an aesthetic

origin.

To Top

History – Keith Laney

On March 7, 2002 independent researcher Wilmer Faust presented an

odd hillock formation captured in MOC image M1402185, to our

attention. The rectangular areas along the upper edge of the hillock

on an S-facing slope along the Northwest rim of the huge Argyre

Basin are what interested him most. Faust noted compartmentalized

structural features throughout its topography including a formation

reminiscent of a gigantic bird.

Images showing the feature and obtained for this study were

processed from raw data imq files via MSSS, subjected to the same

established procedures used in the processing of the MER2003 landing

site selection MOCs. MOC images, though high quality, rarely

decompress from IMQ into a quality high enough for detailed viewing.

The compression artifacts, data drops, and streaking inherent due to

the nature of the camera and data transferal methods are actually

only a slight hindrance. They can be removed from the images with a

little finesse and the appropriate software.

What follows are general steps used in decompressing, de-streaking,

clarifying, contrast adjusting and optimizing MOC images into file

size manageable yet quality .PNGs.

Processing Steps

1. Decompression

Decompress the .imq or .img file using the software of your

choice. A preliminary visual evaluation of the image can be done

now. Proceed to save it in uncompressed format for further

processing.

2. Dealing with Dropouts (if applicable)

Open the image in image editing software.

* If the image is

error free, and clear of data drops (bands that run across the

images in black/white strips or “fuzz”) save it as a .raw file,

and note the image size (***x***** pixels)

[or]

* If error bands or other data drops are visible further

steps must be taken as follows:

. Using the select tool set on rectangular shape, surround the

errors and cut these damaged areas from the darker albedo

images, or . Flood fill color them in solid black on higher

albedo images. . Save these corrected images as a .raw image and

note the image size (***x*****)

You lose those areas, but they are damaged and unusable anyway.

Take care to get them all. Left there they spread through the

histogram and distort the de-streaking and adjusting process.

3. De-streaking

The raw image is then de-streaked using a comb filter.

4. Final Enhancement

The resulting de-streaked image is then

opened in imaging software and finely tuned.

Apply clarifying, contrast & gamma adjusting, sharpening and various

other filters gently, noting the results on the histogram as the

grayscale potential begins to take good shape, with the surface

details becoming clearer and better defined as the albedo

differences are defined more sharply. The image was saved in PNG

format and minimal compression.

Final Notes

The average human eye has the ability to differentially

recognize between 12 to 16 shades of grey . Best results are to be

had when the widest variety of these 12 shades is distributed evenly

across the image.

After processing, the images were then aspect corrected using the

figures given in the image’s ancillary data, oriented N/S, and file

size optimized. All images in this study have been aspect corrected

but not map projected, which was unnecessary to the content.

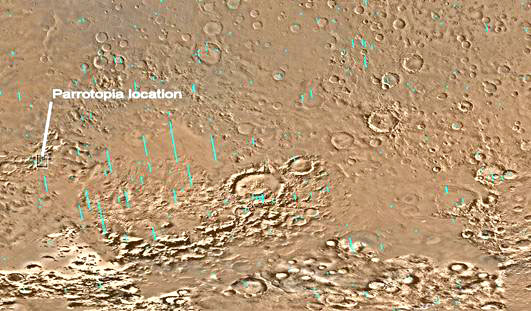

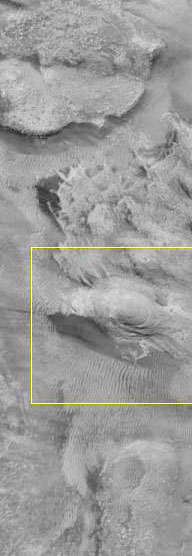

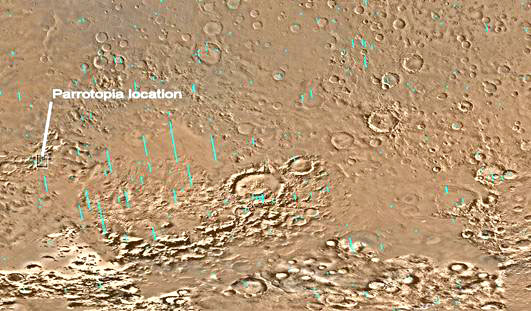

Figure 1

The Parrotopia Complex (M1402185)

Image courtesy Keith Laney

Note the profile of a full-bodied bird at the upper most portion of

this strip. The image is presented north south oriented and the

feature is boxed in yellow. It should be noted here that NASA

provides a north south orientation and a version as seen by the

camera as it passes over the surface. This means that the image is

oriented in both directions on the NASA site.

To Top

Avian Geoglyph at Argyre Basin – Wilmer

C. Faust

The following descriptions denote the anatomical features of the

proposed parrot formation that are detected within the source image

M1402185 (Figure 2). Starting at the head the mandibles appear

correctly shaped and illustrate typically serrated aspects in the

appropriate locations.

The mandibles appear hinged and

partially opened, revealing a tongue feature nested in the upper

beak. There is evidence of a cere, just behind the upper mandible,

with the suggestion of a nostril.

The eye appears correctly positioned and illustrates its typical

aspect when a parrot is looking forward as viewed from the side. The

remainder of the frontal and lateral aspects of the head gives the

visual impression of a light colored eye patch, which is a very

prominent aspect of many parrots.

Behind the hood line of the neck is the main body of the bird. In

comparing the shape of the breast to the exposed back between the

wing covers, to the wing cover size itself, the head size and the

overall body length appears correctly proportioned. The wing covers

are remarkable in their accuracy, in particular the lie of the

feathers when the wings are folded.

The left leg structure is represented with a visible

clawed foot.

Finally, the area that forms the tail feathers is somewhat less

distinct. This is due in part to the fact that a portion of the tail

feathers are cut off by the edge of the source image providing only

a suggestion of such a feature.

Figure 2

The Avian Formation

(Detailed crop of M1402185)

Image courtesy Keith Laney

To Top

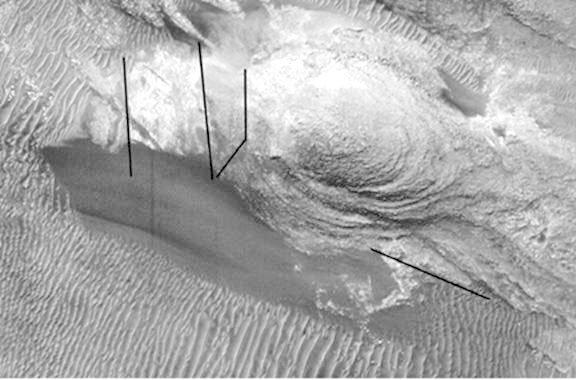

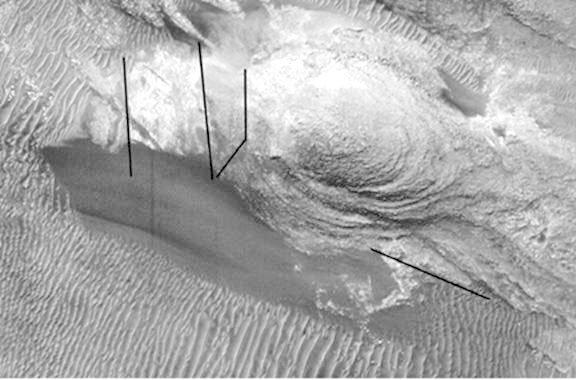

Geological analysis – William R. Saunders

This area contains many non-conforming and complex features (Figure

1) however it is the parrot-like formation that is of most interest

and will be discussed here. The avian structure in question is

composed of five segments: the beak, the head, the neck, the body

including left wing and tail feathers and the legs/feet (Figure 3).

These segments are differentiated by structure, albedo effect,

patterning and possibly lithology.

Figure 3

Five Segments of the Avian Formation

(Detailed crop of M1402185 with line annotations by William R.

Saunders)

Image courtesy Keith Laney

The central mound (according to the veterinarian’s analysis) which

forms the body, left wing and tail is most likely composed of

sandstone or siltstone and has striations which give the impression

of feathering. Initial interpretation is that these markings are

caused by erosion of horizontal stratigraphy by lateral water action

or wind erosion. It would seem that an almost cyclonic wind action

occurring at one place over a long period of time would be needed to

form the circular “feathered” wing striations.

The surrounding dunes however, indicate

prevailing winds from west to east which would not expose the east

side of the mound to abrasive wind erosion. It would seem that an

almost cyclonic wind action occurring at one place over a long

period of time would be needed to form the circular “feathered” wing

striations. Another hindrance to this explanation is that this type

of violent wind process or the necessary water action is not evident

elsewhere in the surrounding area.

The upper portion of the neck (Figure 5 F) is obscured by talus or

mass flow material from the mound. The lower portion of the neck

appears to be a continuation of the mound; however its multi-layered

truncation is irregular and does not conform to the layering pattern

seen in the body/wing.

If this irregular edge were caused by

folding there should be evidence of disturbance on either side,

which there is not. The texture and albedo of the face (Figure 6 L)

is anomalous to the area and shows no evidence of fluvial or wind

erosion or deposition consistent with what would be necessary to

form the striations seen on the body. There is a large mound or

pyramidal structure exactly positioned in the location of an eye

(Figure 5 &6 C). Shadow highlights this effect.

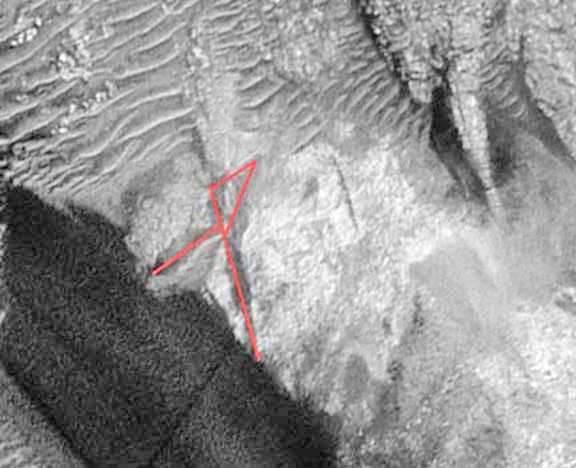

The lithology of the beak appears to be an isolated composition with

irregular patterning on its surface (Figure 4). What could be

considered to be cross faulting and or block faulting conveniently

separates the beak from the face and forms the mouth, tongue and

crown. Evidence that faulting has occurred at all is indeed arguable

as it would have to be extremely localized and multi-directional as

there is no evidence of faulting in the dunes around this feature.

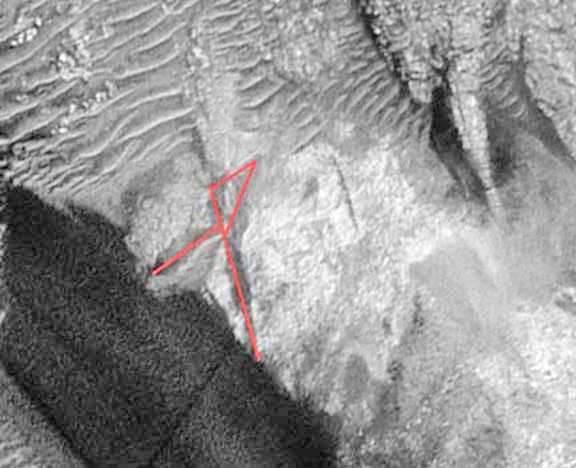

Figure 4

Multi-Directional Contours

(Detailed crop of M1402185 with line annotations by William R.

Saunders)

Image courtesy Keith Laney

Another anomalous aspect to this parrot-like structure is the dark

material beneath it that extends from the feet to beyond the beak

(Figure 5 N & H). This dark material appears to be aeolian detritus.

It is suggested that this material is composed of iron pistolite

weathered from the mound. This material has an air brushed

appearance and does not form dunes. If it is wind deposited, its

trapping mechanism is suspect.

Lastly the legs/feet (Figure 5 O, N, P) are note worthy in that one

would anticipate the composition to be of the same material as the

body and tail, however their structure is multi directional and

generally perpendicular to the body and tail. Conveniently for the

viewer, neither the dunes nor the dark material obscure them. It has

been suggested that faulting, possibly active, is at work forming

the legs and feet.

Once again the faulting would have to be

conveniently localized.

In conclusion, given the lack of similar lithology and evidence of

similar geo-processes in the immediate area, this structure is

indeed anomalous. Numerous geomorphologic and geological processes;

including, non-extensive, multi-directional faulting, erosion and,

deposition all occurring at exactly the right place and time would

be needed to produce this structure.

To Top

Veterinarian Analyses of the Anatomical

features of the Avian formation – Doctor A.J. Cole and Doctor Joseph

M. Friedlander

Two veterinarians have

examined this avian feature exhibited within the Argyre Basin. The

first doctor was aware of prior theories of artificial objects on

Mars, while the second doctor had no prior awareness of any theories

of artificial objects on Mars. Both doctors impartially and

independently evaluated the features of the proposed avian

formation, having access to both a printed hard copy and

computer-displayed image of the complete formation.

Doctor A.J. Cole:

Jackson Veterinarian Hospital,

Jackson, New Jersey

There are distinct anatomical similarities to the features found

on the formation located at Argyre Basin and the avian species.

Centrally there appears to be a midstructural breast and abdomen

with protruding structures resembling primary flight feathers

with feather shafts attached to the dorsal aspect of the image.

On the left (rostral) aspect of the structure there is a

resemblance to head and facial features ending at the nape of

the neck. The head includes a lateral left eye, a hinged beak

with a blunted tongue between a parted lower mandible. Between

the “eye” structure and beak there is an arching structure

resembling a cere without evidence of a nostril that may be

obscured by a crest or comb feature.

Below the abdomen (ventrocaudally)

there appears to be a claw feature consisting of a three or

four-toed foot with a bend at the equivalent of the tarsus.

There is only a hint of a paired second foot, which is

unresolved. The structural formation to the far right of the

body (caudally) resembles tail feathers; however no inference

can be made about a tapered or blunted tail in the available

image. The following analytical drawing (Figure 5) identifies a

set of 17 points of confirmation that Veterinarian A.J. Cole

believes provides evidence that the formation at Argyre Basin

not only represents an avian creature, but it’s sculptured

features appear anatomically correct.

Figure 5

Parrotopia Formation

Analytical Drawing with notations by Doctor A.J. Cole.

Drawing by George J. Haas

(Image source: M1402185)

A. Cere. B. Crest. C. Eye. D. Primary Flight Feathers (right

wing). E. Feather Shafts F. Hood Line (neck). G. Body (folded

left wing). H. Beak. I. Tongue. J. Jaw. K. Head. L Abdomen. M.

Claw. N. Foot and Toes. O. Tarsus Joint. P. Tibia. Q. Tail

Feathers.

Doctor Joseph M Friedlander:

Adamston Veterinarian

Clinic, Brick, New Jersey

Examination of the formation at Argyre Basin reveals features of

the avian species. Rostrally (left), one can visualize the beak

with its maxilla mandible surrounding the tongue. Features of

the head are clearly visible. The cere is noted dorsal to the

maxilla. The orbit, papillary margin and opening of the external

ear canal are evident. The head looks featherless. Down feathers

are seen in the cervical area. Visualized in the thoracic region

is the left wing folded in a natural position. Primary feathers

cover this region. Ventrally is the pectoral area ending at the

point of the keel.

Caudally (to the right) is the

abdomen and left pelvic limb. Three digits, tarsometatarsus and

tibiotartus are visible. The photograph includes the proximal

portion of tail feathers. Just rostral and dorsal to the tail

feathers is a change in feather pattern of the pygostyle (prcen

gland). The following analytical drawing (Figure 6) identifies a

set of 10 points of confirmation that Veterinarian Joseph M.

Friedlander believes provides evidence that the formation at Argyre Basin

not only represents an avian creature, but its

sculptured features appear anatomically correct.

Figure 6

Parrotopia Formation

Analytical Drawing with notations by Doctor A.J. Cole.

Drawing by George J. Haas

(Image source: M1402185)

A.Cere. B. Part of Crown. C. Eye. D. Ear. E. Down Feathers F.

Folded Wing.

G. Preen Gland H. Tail Feathers. I. Maxilla. J. Tongue. K.

Mandible. L. Face.

M. Abdomen. N. Digits. O. Tarsometatarsus. P. Tibiotartus

To Top

Comparison of a random feature on Mars at

Argyre Basin – William R. Saunders

Conducting a random search of the surrounding area of Argyre Basin

no suitable comparative features were found. Subsequently a search

was expanded to the outer regions, in which a comparable feature was

found with similar contours within the Dao Vallis region of Mars.

The comparable mound feature from Dao Vallis is displayed in Figure

7 and a cropped portion of the Argyre Basin formation is displayed

in Figure 2.

The appearance of sand furrowing

indicates water has surrounded both of these landforms in the past

leaving island remnants. The mound from the Dao Vallis region shows

a typical oval shape expected from the movement of water around the

feature with a slightly truncated left side and a small point bar on

the right. In contrast, the multiple features exhibited in the

formation found at the Argyre Basin area do not present the same

expected characteristics.

There is no truncation on either side, nor

is a point bar formation present. The formation at Argyre Basin

(Figure 2) also has what would appear at first to be multilayered

strand lines that are not present on the mound at Dao Vallis. The

conclusion being that the formation at Argyre Basin has undergone

post fluvial alteration.

Figure 7

Mound Formation at Dao Vallis

Crop from MOC Image R1502471 –

rotated right 90°

Image courtesy of Keith Laney

To Top

Aesthetic analysis – George J. Haas

The formation at Argyre Basin appears to be the result of a

composite structure of unrelated geological materials that were

altered to express the prominent features of an avian creature. The

topographical features appear to include an oval shaped mound that

conforms to the shape and size of a bird’s body including a folded

left wing (Figure 5G). Adjoining features to the left side of the

body-shaped mound suggest a composite of structural elements that

resemble a bird’s head (Figure 5K). The head includes an eye

formation (Figure 5C) and a parted beak (Figure 5H) with a fleshy

wattle-like crest (Figure 5B). Additional elements form an extended

left leg (Figure 5 O&P) and clawed foot (Figure 5 M&N).

There is also evidence of an extended

right wing along the back (Figure 5D) and tail feathers (Figure 5Q)

that may extend beyond the image. The majority of comparative

examples of manipulated terrestrial geology come to us in the form

of earthworks that were created by ancient cultures throughout North

and South America. Because there are a limited number of examples of

animal and figurative earthworks in the available database, only two

meet the criteria of this study with comparable detail and content.

The first is a 5,000-year-old eagle shaped Geoglyph located in the

town of Eatonton Georgia. A bed of quartz stones form a silhouette

of an eagle hovering within a circular mound. The body measures over

100 feet from head to tail and has a wingspan of over 120 feet

(Figure 8). The overall shape of the eagle is symmetrical in design,

featuring a set of out stretched wings, tail feathers and a head

that faces eastward.

As seen in the illustration, its contours

project only the simplest form of a bird without providing

additional details.

Figure 8

Eagle Effigy Mound: Eatonton Georgia

Drawing by George J. Haas

(Image source: National Geographic, vol.142, no.6, page 784)

A second example of an avian earthwork

is etched on a hillside in the Peruvian Andes, not far from the

famous

Nazca lines. The Peruvian pictograph is formed by a set of

conjoined lines that create the impression of a standing bird

(Figure 9). Although the awkward shape of the Peruvian pictograph is

not anatomically correct, the overwhelming consensus is that it

indeed represents the generic form of a small bird.

Figure 9

Bird Pictograph Nazca.

Drawing by George J. Haas

If this simple mound and hillside

rendering are accepted as intentional works of art by aerial

observations, then it would be reasonable to say that the formal

organization expressed within the Martian feature is not the result

of mere chance. This is beyond the modeling of relief sculpture and

there are no terrestrial Geoglyphs that induce such a visual

impression, as seen within the avian formation at Argyre Basin.

To Top

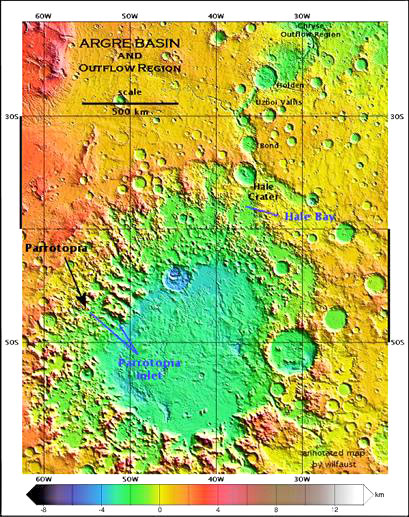

Regional Context -Wilmer C. Faust

The site of the complex of features we have identified lies within

the northwest quadrant of the Argyre Basin, which is centered on the

planet Mars at about 50 degrees south latitude, 43 degrees west

longitude Figure 12. The result of an ancient impact, the Argyre

Basin is the second largest cratered landform in the southern

hemisphere of the planet. It is ringed by ramparts rising several

kilometers above its central plain, known today as Argyre Planitia,

and is of roughly circular but somewhat irregular outline likely

resulting from environmental alteration subsequent to the primary

impact event.

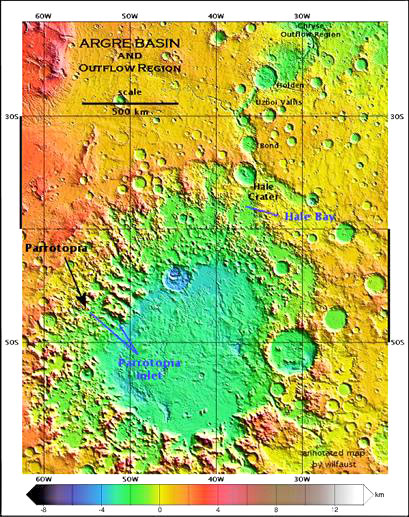

Figure 12

MOC planetary map showing the location of the M14 Series of images

with the exact location of M1402185

Annotated by Jim Miller Original

map at this address:

NASA/JPL/Malin

Space Science Systems

The encompassing Basin scarps and bluffs

are in turn surrounded by the generally more greatly elevated

Southern Highlands. Within the Basin is found a prominent but much

fragmented zone of rugged elevations, the Neiridium Montes, mainly

concentric with and extending from or near to the defining ramparts

approximately one-quarter of the diameter of the Basin towards the

central plain.

The Neiridium Montes are sufficiently prominent to

give a geophysical character possibly unique on Mars to the Basin

itself, with prominent elevations alternating with much lower institial plains and valleys more closely approximating the lower

elevations of Argyre Planitia. See Figure 13 for a graphic depiction

of this description.

Figure 13

MOLA image of Argyre Basin

(Annotated Map by Wil Faust)

From a previously published study based on topographic data produced

by the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter instrument (MOLA), it is now

known that at least once and perhaps more often the Argyre Basin was

an outflow source of water which emptied through a sequence of

lower-lying landforms toward the north-northeast (Figure 13). A

thorough assessment of the archaeohydrology of the Argyre Basin is

beyond the scope of the present examination. It is important here to

note that this area is near an inferred old polar cap, and some of

the geology is remarkably similar to southern Polar Regions.

To Top

Conclusion -

Wilmer C. Faust, Jim Miller, George

J. Haas, William R. Saunders

The overall impression of this area is

that regardless of the nature of the rock and sediment, the nature

of depositional and erosional forces, the avian formation is indeed

an anomalous structure when compared with the rest of the

topography. While there are known geological mechanisms that could

have created the anatomical accuracies presented in this formation,

it is highly unlikely that the entopic effects of environmental

degradation could have produced such prominent orientations and

postural representations at the same time, in the same place within

a 1.5 square mile area.

With respect to the modeling of these

anatomical features the visual perceptions of this avian formation

suggest it’s the result of an organized design as opposed to an

illusionary projection. Therefore it is conceivable that this avian

formation was originally a natural landform that was artificially

modified to illustrate all the required features and details of a

recognizable bird.

To Top

Biographical information about the

authors:

-

Wilmer C. Faust III acquired a

Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Dartmouth College, NH,

and a Master’s in Urban Planning from Penn State Harrisburg. He co-founded the Historic Harrisburg Association and his

memberships to scientific and research organizations include the

American Institute of City Planners, Harrisburg Astronomical

Society, SETI, Anomaly Hunters and Project Teardrop.

-

George J. Haas is a sculptor and a

former director of the Sculptors’ Association of New Jersey. He

is a member of both The Pre-Columbian Society at the University

of Pennsylvania and The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute in

San Francisco California and is the co-author of the book

The Cydonia Codex - Reflections from Mars.

-

Keith Laney is a digital-imaging and

software applications specialist, known for his imaging

contributions to NASA History, the MER2003 Rover missions and

NASA’s Landing Sites Project. He is also working on the complete

Apollo program image archives for NASA/JPL

-

Jim Miller is an independent

researcher and the founder of a Mars research group where this

feature was first presented and discussed. He has also written

and edited several company newsletters.

-

William R. Saunders graduated from

the University of Alberta in Edmonton in 1977 with a Bachelor of

Science degree in geomorphology. He currently works as a

petroleum geoscience consultant in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He

is the co-author of the book

The Cydonia Codex - Reflections from Mars.

Contributor:

Keith Phillips is an engineer. He

worked at 7 different Silicon Valley startup companies as a

manufacturing engineer, engineering supervisor, applications

engineer, applications engineering supervisor, technical support

supervisor and microwave and semiconductor engineer.

To Top

FOOTNOTES:

-

Keith Phillips provided the

mathematical, statistical computations NASAView 2.5.8 or

equivalent decompression software recommended Paint Shop Pro

or Photoshop recommended Comb2 or Mocomatic digital image

comb filter recommended

http://www.engr.udayton.edu/faculty/jloomis/ece563/notes/color/GrayScale/grays.html

http://chesapeake.towson.edu/data/all_image.asp

-

The following list represents

the data set of MOC images that were examined by George J.

Haas, Jim Miller and William R. Saunders in an effort to

locate a comparable image to the Parrotopia formation

observed in MOC image M1402185.

Those images include:

-

M04-00606 North facing slope

of crater.

-

M04-00926 Argyre Basin rim.

-

M13-00036 North Western

Argyre Basin.

-

M13-00220 SW Argyre Planitia.

-

M13-00471 Traverse of

Mountains W of Argyre Planitia.

-

M20-00992 sample terrain in

SW Argyre Rim Mountains.

-

R15-01672 North Central

Argyre Basin.

-

R15-01571 sample mountain

plain west of Argyre.

-

R15-01194 North Eastern

Argyre Planitia.

-

Wilmer Faust wrote his sections

of the paper prior to his untimely death on 7/25/2005. There

were extensive descriptions and dissertations regarding the Argyre Basin, its hydrology and possible theories for the

placement of this feature in this location. All of this

material was beyond the scope of this paper but is preserved

on a web site dedicated to the continued research of this

feature.

To Top

|