|

Carbon-dating the Great Pyramid

from

The Message of the Sphinx

The evidence presented in this book concerning the origins and

antiquity of the monuments of the Giza necropolis suggests that the

genesis and original planning and layout of the site may be dated,

using the tools of modern computer-aided archaeoastronomy, to the

epoch of 10,500 BC. We have also argued, on the basis of a

combination of geological, architectural and archaeoastronomical

indicators that the Great Sphinx, its associated megalithic

‘temples’, and at least the lower courses of the so-called ‘Pyramid

of Khafre’, may in fact have been built at that exceedingly remote

date.

It is important to note that we do not date the construction of the

Great Pyramid to 10,500 BC. On the contrary, we point out that its

internal astronomical alignments -the star-shafts of the King’s and

Queen’s Chambers -are consistent with a completion date during

ancient Egypt’s ‘Old Kingdom’, somewhere around 2500 BC. Such a date

should, in itself, be uncontroversial since it in no way contradicts

the scholarly consensus that the monument was built by Khufu, the

second Pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, who ruled from 2551 -2528 BC.

What places our theory in sharp contradiction to the orthodox view,

however, is our suggestion that the mysterious structures of the

Giza necropolis may all be the result of an enormously

long-drawn-out period of architectural elaboration and development-

a period that had its genesis in 10,500 BC, that came to an end with

the completion of the Great Pyramid come 8000 years later in 2500

BC, and that was guided throughout by a unified master-plan.

According to orthodox Egyptologists, the Great Pyramid is the result

of only just over 100 years of architectural development, beginning

with the construction of the step-pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara not

earlier than 2630 BC, passing through a number of ‘experimental’

models of true Pyramids (one at Meidum and at two Dashour, all

attributed to Khufu’s father Sneferu) and leading inexorably to the

technological mastery of the Great Pyramid not earlier than 2551 BC

(the date of Khufu’s own ascension to the throne). An evolutionary

‘sequence’ in pyramid-construction thus lies at the heart of the

orthodox Egyptological theory -a sequence in which the Great Pyramid

is seen as having evolved from (and thus having been preceded by)

the four earlier pyramids.

But suppose those four pyramids were proved to be not earlier but

later structures? Suppose, for example, that objective and

unambiguous archaeological evidence were to emerge- say, reliable

carbon dated samples -which indicated that work on the Great Pyramid

had in fact begun some 1300 years before the birth of Khufu and that

the monument had stood substantially complete some 300 years before

his accession to the throne?

Such evidence, if it existed, would render obsolete the orthodox Egyptological theory about the origins,

function and dating of the Great Pyramid since it would destroy the Saqqara ~ Meidum ~ Dashour ~ Giza ‘sequence’ by making the

technologically-advanced Great Pyramid far older than its supposed

oldest ‘ancestor’, the far more rudimentary step-pyramid of Zoser.

With the sequence no longer valid, it would then be even more

difficult than it is at present for scholars to explain the immense

architectural competence and precision of the Great Pyramid (since

it defies reason to suppose that such advanced and sophisticated

work could have been undertaken by builders with no prior knowledge

of monumental architecture).

Curiously, objective evidence does exist which casts serious doubt

on the orthodox archaeological sequence. This evidence was procured

and published in 1986 by the Pyramids Carbon-dating Project,

directed by Mark Lehner (and referred to in passing in his

correspondence with us). With funding from the Edgar Cayce

Foundation, Lehner collected fifteen samples of ancient mortar from

the masonry of the Great Pyramid. These samples of mortar were

chosen because they contained fragments of organic material which,

unlike natural stone, would be susceptible to carbon-dating. Two of

the samples were tested in the Radiocarbon Laboratory of the

Southern Methodist University in Dallas Texas and the other thirteen

were taken to laboratories in Zurich, Switzerland, for dating by the

more sophisticated accelerator method. According to proper

procedure, the results were then calibrated and confirmed with

respect to tree-ring samples.

The outcome was surprising. As Mark Lehner commented at the time:

The dates run from 3809 BC to 2869 BC. So generally the dates are …

significantly earlier than the best Egyptological date for Khufu …

In short, the radiocarbon dates, depending on which sample you note,

suggest that the Egyptological chronology is anything from 200 to

1200 years off. You can look at this almost like a bell curve, and

when you cut it down the middle you can summarize the results by

saying our dates are 400 to 450 years too early for the Old Kingdom

Pyramids, especially those of the Fourth Dynasty … Now this is

really radical … I mean it’ll make a big stink. The Giza pyramid is

400 years older than Egyptologists believe.

Despite Lehner’s insistence that the carbon-dating was conducted

according to rigorous scientific procedures (enough, normally, to

qualify these dates for full acceptance by scholars) it is a strange

fact that almost no ‘stink’ at all has been caused by his study. On

the contrary, its implications have been and continue to be

universally ignored by Egyptologists and have not been widely

published or considered in either the academic or the popular press.

We are at a loss to explain this apparent failure of scholarship and

are equally unable to understand why there has been no move to

extract and carbon-date further samples of the Great Pyramid’s

mortar in order to test Lehner’s potentially revolutionary results.

What has to be considered, however, is the unsettling possibility

that some kind of pattern may underlay these strange oversights.

As we reported in Chapter 6, a piece of wood that had been sealed

inside the shafts of the Queen’s Chamber since completion of

construction work on that room, was amongst the unique collection of

relics brought out of the Great Pyramid in 1872 by the British

engineer Waynman Dixon. The other two ‘Dixon relics’ - the small

metal hook and the stone sphere - have been located after having

been ‘misplaced’ by the British Museum for a very long while. The

whereabouts of the piece of wood, however, is today unknown.

This is very frustrating. Being organic, wood can be accurately

carbon dated. Since this particular piece of wood is known to have

been sealed inside the Pyramid at the time of construction of the

monument, radiocarbon results from it could, theoretically, confirm

the date when that construction took place.

A missing piece of wood cannot be tested. Fortunately, however, as

we also reported in Chapter 6, it is probable that another such

piece of wood is still in situ at some depth inside the northern

shaft of the Queen’s Chamber. This piece was clearly visible in

film, taken by Rudolf Gantenbrink’s robot-camera Upuaut, that was

shown to a gathering of senior Egyptologists at the British Museum

on 22 November 1993.

We are informed that it would be a relatively simple and inexpensive

task to extract the piece of wood from the northern shaft. More than

two and a half years after that screening at the British Museum,

however, no attempt has been made to take advantage of this

opportunity. The piece of wood still sits there, its age unknown,

and Rudolf Gantenbrink, as we saw in Chapter 6, has not been

permitted to complete his exploration of the shafts.

“The Missing Cigar Box” and “Cleopatra’s Needle and Victorian

Memorabilia”

from

The Orion Mystery

The Missing Cigar Box

A few days later, on 23 November 1872, two letters followed from

John Dixon to Piazzi Smyth. In one letter Dixon informed

Smyth that

he had dispatched the relics to him :

These relics are packed in a cigar box and carried by passenger

train. They consist of Stone Ball, Bronze Hook and Wood secured in

glass tube … copy, photo or anything you like with them … but return

them without delay as many are calling to see them and when next

week The Graphic has a drawing of these in … there will be a rush …

Is there any chance the British Museum giving a few hundred for

these relics? If so, I’d spend the money in a great clearance and

exploration [of the Pyramid base] ... I’ll beg them after their

existence [the Epilogue relics] become known …

In the second letter Dixon discussed Smyth’s ‘theory’ that these

shafts in the Queen’s Chamber might have been ‘air channels’:

Your remark as to the terminology of the new channels is forceful

and good but I dissent from adopting on too hasty an assumption the

theory that they are air channels for the obvious reason that they

have been so carefully formed up to but not into the chamber. That 5

inches of so carefully left stone is the stumbling block to such a

supposition. And again, one at any rate of them I am convinced from

its appearance - so clean and white as the day it was made - cannot

have any connection with the external atmosphere. It was here (in

the north passage) we found the tools …

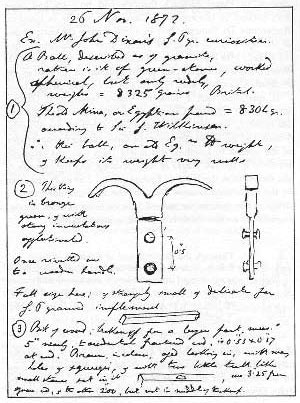

The now famous cigar box with the relics inside arrived safely on 26

November 1872 in the hands of Piazzi Smyth in Edinburgh. He entered

this in his diary and also produced a full-size sketch of the metal

‘tool’. Piazzi Smyth also correctly noted that the ‘tool’ was ‘…

strangely small and delicate for [being a] Great Pyramid implement

…’

On the 4 October 1993 I went to the Newspaper Library of the British

Library at Colindale. I looked up the December 1872 issues of The

Graphic and, in the issue 7 December 1872 I found John Dixon’s

article on P.53° (text) and P.545 (drawings).

From these, and Piazzi Smyth’s own diagrams and commentaries of the

relics, I concluded that the ‘bronze tool’ or ‘grapnel hook’ was an

instrument used for a ritual, probably something to do with the

‘opening of the mouth’ ceremony. It reminded me of a snake’s forked

tongue. Such a ‘snake-like’ instrument was actually used in this

ceremony and some good depictions can be seen in the famous Papyrus

of Hunifer at the British Museum.

The discovery of this implement

inside the northern shaft, which we now know pointed to the

circumpolar constellations - the sky region which is identified with

this ceremony - adds further support to this thesis. Professor Z. Zaba, the astronomer and Egyptologist, has argued that an instrument

called ‘Pesh-en-kef’, and shaped very much like the ‘tool’ found in

the channel by Dixon, was, in actual fact, used in very ancient

times in the ceremony of the ‘opening of the mouth’. Furthermore,

Zaba proved that the ‘Pesh-en-kef’ instrument, fixed on a wooden

piece and in conjunction with a plumb-bob, was used to align the

pyramid with the polar stars. It now seemed very likely that a

priest placed the ritualistic tools inside the northern shaft from

the other side of the wall of the Queen’s Chamber.

Where could these relics be now? If not at the British Museum, then

where? I took the diagrams of the relics to Dr Carol Andrews at the

Egyptian Antiquities Department of the British Museum, but she

seemed certain that they were not in their keep. Her first reaction

was that the items, judging from the diagrams, did not look ‘old

enough’, and she thought perhaps they were put in the shafts at a

later date. But I reminded her that the shafts were closed from both

ends until Waynman Dixon and Dr Grant opened them in

1872. The good

state of preservation was actually explained by John Dixon in a

letter dated 2 September 1872:

The passage being hermetically sealed, there was no appearance of

dust or smoke inside - but the walls were as clean as the day it was

made…

Dixon was right, of course. With such a sealed system the relics

were free from air corrosion. I gave Dr Andrews my opinion that the

‘tool’ was a Pesh-en-kef instrument, and also a sighting device for

stellar alignments. Dr Andrews favoured the latter idea, but said

that no Pesh-en-kef instrument of this shape was known before the

Eighteenth Dynasty. I then showed the diagrams to Dr Edwards in

Oxford and he, too, was compelled to support this idea but, unlike

Dr Andrews, he recognized the instrument as a type of Pesh-en-kef.

Both Rudolf Gantenbrink and I tend to agree with him on this.

Cleopatra’s Needle and Victorian Memorabilia

The next place to check was at the Sir John Soanes Museum at

Lincoln’s Inn. John and Waynman Dixon seemed to know the curator,

Dr Bunomi, at the time and so did Piazzi Smyth. But the archivist

there, Mrs. Parmer, was clear that no such items were ever given to

the Museum. I told her of Bunomi’s interest in Piazzi Smyth’s

theories and how he had been very excited by the arrival of

Cleopatra’s Needle in London. Apparently Dr Bunomi died in 1876,

during the early stages of the operation to bring the obelisk from

Alexandria. While we talked, Mrs. Parmer remembered a curious event

about Dr Bunomi: after his death, he had had placed on the roof of

the museum a Doulton ware type jar full of curious memorabilia.

It was then that I suddenly remembered John Dixon’s involvement with

the Cleopatra’s Needle affair. Both he and his brother, Waynman, had

been contracted by Sir Erasmus Wilson and Sir James Alexander to

supervise the transportation of the obelisk to London. But it was

John who was primarily involved in the last stages of the operation

and the erection of the monolith at the Victoria Embankment. The

story appeared in the Illustrated London News of the 21 September

1878. I drove to the monument and read the commemoration

inscriptions; one, on the north face of the monument, read :

Through the Patriotic zeal of Erasmus Wilson, F.R.S., this obelisk

was brought from Alexandria encased in an iron cylinder. It was

abandoned during a storm in the Bay of Biscay, recovered and erected

on this spot by John Dixon, C.E., in the 42nd year of Queen Victoria

(1878).

According to the Illustrated London News of 21 September 1878, all

sorts of curious memorabilia and relics were buried in the front

part of the pedestal. These were put there by John Dixon himself in

August 1878 during the construction of the pedestal, inside two Doulton ware jars. Among the strange Mystery items were ‘photographs

of twelve beautiful Englishwomen, a box of hairpins and other

articles of feminine adornment … a box of cigars …’

Could John Dixon have put the ancient relics which he once kept in a

‘box of cigars’ under the London Obelisk? I telephoned an historian

of the England National Heritage, Mr. Roger Bowdler, but he did not

think they had any details of the items under the Obelisk. He

suggested I try the Record Office of I the Metropolitan Board of

Works, who apparently were responsible for the operations to raise

the obelisk in 1878. A frustrating search in the archives brought no

result. Another search in the National Register of Archives also

proved a dead end. We cannot help wondering if these ancient relics

- indeed, perhaps the very sighting instruments that were used to

align the Great Pyramid to the stars - are in a cigar box under

Cleopatra’s Needle in London. Or perhaps they lie elsewhere, in some

dark attic or cupboard in one of the many London antiquarian shops.

We shall, perhaps, never know.

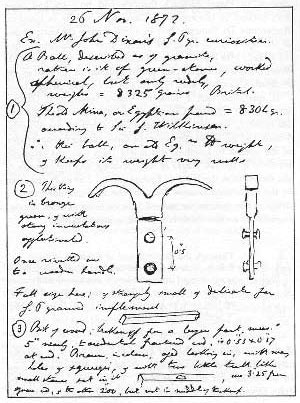

Entry 26 November 1872

from Piazzi Smyth’s diary

Discoveries in the Great Pyramid

1. Original Casing Stone from North Side

2. Granite Ball, 1 lb 3 oz

3. Piece of Cedar, apparently a Measure

4. Bronze Instrument with portion of the wooden handle adhering

to it.

The Last 3 items were found in

the northern shaft of the Queen’s

Chamber in 1872

|