|

Queen’s Chamber

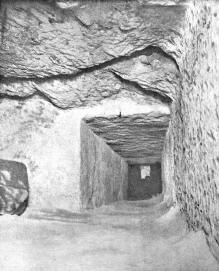

As mentioned before, if you continue at the junction of the

ascending passage and Grand Gallery through the horizontal passage,

which runs for 127 feet, you wind up in the Queen’s Chamber, which

is directly beneath the apex of the pyramid. This passage is 3 feet

9 inches high and 3 feet 5 inches wide. A sudden drop of 2 feet

occurs towards the end of the passage before the entrance to the Queen’s Chamber.

The drop or step in the horizontal passage

leading to the Queen’s

Chamber

The Queen’s Chamber has a rough floor and a gabled limestone roof.

The name Queen’s Chamber is a misnomer. The custom among

Arab’s was to place their women in tombs with gabled ceilings (as

opposed to flat ones for men), so this room came to be labeled by

the Arab’s as the Queen’s Chamber.

The chamber dimensions are 18

feet 10 inches by 17 feet 2 inches. It has a double pitched ceiling

20 1/2 feet at its highest point, formed by huge blocks of limestone

at a slope of about 30 degrees. When this chamber was first entered,

the walls were encrusted with salt up to 1/2 inch thick. This has

been removed since then, most likely when the chamber was cleaned.

Salt encrustation was also found on the walls of the subterranean

chamber. The cause is unknown.

The Queen’s chamber showing the Niche in the east wall

and high

gabled roof to the left

There is a report by an Arab, Edrisi, who died around 1166 AD. He

entered the pyramid through the forced entrance made by Al mamoun and describes not only an empty granite box in the king’s

chamber, but also a similar one in the queen’s chamber.

It was uninscribed and undecorated just like the one in the king’s chamber.

What ever happened to this granite box in the queen’s chamber if it

ever existed remains a mystery.

The Niche in the

Queen’s Chamber

Colonel Vyse also dug up the floor in the Queen’s chamber but only

found an old basket so they refilled the holes. What ever happened

to this basket remains a mystery. The Niche was originally about 3 ½

feet deep. Throughout the years, explorers have hacked it deeper and

it currently is about several yards deep. The Niche is just over 16

feet high.

We have seen that the airshafts from the King’s Chamber were found

to exit to the outside of the pyramid. It appears that the Queen’s

Chamber airshafts do not lead to the outside but may terminate

within the pyramid. The discovery of these airshafts in the Queen’s

Chamber is an interesting story. John and Waynman Dixon, in 1872

thought there may be similar shafts in the Queen’s chamber. A crack

was observed in the south wall of the Queens Chamber in a spot where

they suspected an airshaft might be located. They inserted a wire

into this crack and it went through a certain distance. After

chiseling for about 5 inches through the masonry, they broke into

the southern airshaft.

They noticed this airshaft was about 9 inches

square. It went vertically for about 6 feet and than went upward and

disappeared from their sight. They also found the airshaft in the

northern wall by chiseling through the northern wall in the same

location of where they found the air shaft in the Southern wall.

They tried to locate the exit points of these shafts but could not

find any. They even lit a fire in the shafts and the smoke did not

billow back or exit to the outside. Why were these shafts sealed off

with 5 inches of masonry at their ends? Where do they lead?

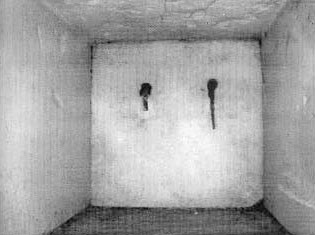

North airshaft of the Queen’s Chamber

Rudolf Gantenbrink in 1993 sent a small robot with a camera up the

southern airshaft in the Queen’s Chamber. After traveling about 200

feet up the airshaft it came to a small door complete with copper

handles. The airshafts are about 9 inches square. In September of

this year, both airshafts were explored using a robot and this

continued search for hidden chambers will be explored in Chapter 5.

Now, we will go back and continue down the descending passage way.

It’s dimensions are the same as the ascending passage, 3 1/2 feet

wide by almost 4 feet high, and slopes down at an angle of about 26

degrees.

Cramped posture necessary in the Descending Passageway

as viewed

from the lower end of the well shaft

The distance of the descending passage to the beginning of the

horizontal subterranean chamber passage is about 344 feet. This

shorter horizontal section leads to a small lesser subterranean

chamber and then continues into the large subterranean chamber.

Lesser Subterranean Chamber

and Subterranean Chamber Passage

This large chamber is a strange place, measuring 46 X 27 feet with

height of about 11 feet. It is cut deep into the bedrock almost 600

feet directly below the apex of the Pyramid. Its ceiling is smooth

and the floor is cut in several rough levels, making it look

unfinished. It has also been referred to as the “upside down room”.

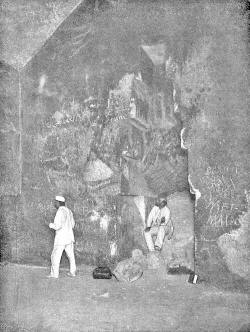

When the Arabs first broke in to the pyramid in 820 A.D., they found

torch marks on the ceiling showing that someone had entered the

pyramid before them and explored these lower chambers. If anything

was here, it was removed.

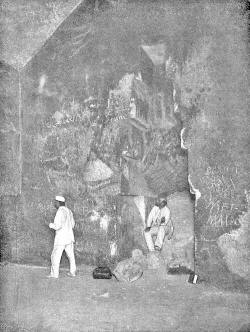

Subterranean Chamber showing east wall and ceiling

Subterranean chamber looking north

showing the entrance doorway from

the horizontal passage and pit

Subterranean Chamber showing the Pit

In the center of this chamber on the east side is a square pit,

which is known as the “bottomless pit”. It is called the “bottomless

pit” since at the time of its discovery; it was not known how deep

it was.

Subterranean chamber

looking north showing the entrance doorway

from the horizontal

passage and pit

Subterranean Chamber

showing the Pit

This Pit in 1838 was measured to be 12 feet deep.

Colonel Vyse,

searching for hidden chambers, had it dug deeper.

The Edgar brother’s account of their visit to the pyramid in 1909

state that,

“In the unfinished floor of the subterranean chamber

appears the large, squarish mouth of a deep vertical shaft. We had

always to avoid walking too near its edge, for the rough uneven

floor of the chamber is covered with loose crumbling debris”.

In the south wall, opposite the entrance, is a low passage (about 2

1/2 feet square), which runs 53 feet before coming to a blind end.

When John and Edgar Morton explored this passage in the early

1900’s, they stated that the floor of this passage was covered with

dark earthy mould, two to three inches deep.

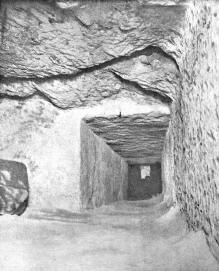

At the intersection where the ascending passage meets with the Grand

Gallery is a hole, which leads to a shaft (known as the well shaft),

which connects, with the descending passage below. This near

vertical tunnel is about 3 feet in diameter. As it continues

downward a grotto opens off the shaft. The shaft than continues

downward to connect with the lower part of the descending passage.

The purpose of this well shaft remains a mystery.

The lower end of the well shaft

as viewed from the opposite wall of

the descending passage

The earliest investigator to give any really scientific data of the

Great Pyramid was the Oxford astronomer John Greaves. He visited

Egypt in 1637 in order to explore thoroughly its pyramids, and in

particular the Great Pyramid. He made a new discovery that others

had missed. At the beginning of the Grand Gallery towards one side,

a stone block had been removed and a passage appeared to have been

dug straight down into the depths of the pyramid. He had discovered

the entrance to the so-called “Well Shaft”.

The opening was a little

over 3 feet wide and notches were carved opposite one another on the

sides of this shaft so someone could climb down with support.

Greaves lowered himself down to about 60 feet, where he found that

the shaft was enlarged into a small chamber or grotto. The shaft

continued below him but it was so dark and the air was foul that he

decided to climb back up. The purpose of this Well Shaft puzzled

him.

The Grotto looking north

He published his investigations under the title,

Pyramidographia: A

Description of the Pyramids in Egypt (1646). This was the first book

ever published just on the Great Pyramid. His work gave a great

stimulus to other investigators, and English, French, German, Dutch,

and Italian explorers soon followed him.

One of the most interesting aspects of archeology is the search for

hidden chambers in ancient structures. We will look at the

historical search for hidden chambers and passageways in the

Great

Pyramid, and you will learn of artifacts that have been found in it.

Hidden Chambers

The possibility of discovering hidden chambers or passages in the

pyramid has interested man for thousands of years. The thought of

finding hidden treasures, the blueprints of the pyramid, lost

scientific information and technological devices of a lost culture

have motivated man to search for a hidden chamber within the pyramid

and in other ancient structures. Before this century, the only way

of conducting this type of exploration was to bore into the

structure, hoping by luck you would hit an undiscovered passage or

chamber. This was done when the Arabs first tried to find an

entrance into the pyramid as described in Chapter 1. Other explorers

have similarly left their mark on the structure with nothing of

significance discovered. Now we have modern scientific instruments

to help us continue the search.

Experiments in the past have been conducted using sophisticated

equipment, which records measurements of magnetic fields, sound

waves, and other fields to try to discover hidden chambers within

these structures. The use of cosmic ray probes, developed by Dr.

Louis Alvarez, who won the Noble Prize for physics, was utilized by

him in 1968 to try to find hidden chambers in Kephren’s pyramid (2nd

largest pyramid).

Dr. Alvarez, along with Dr. Ahmed Fahkry, an

antiquities expert carried out the experiment. Cosmic rays

continually bombard our planet and they lose some of their energy as

they penetrate rocks. If there are hollow spaces in the rock, the

rays loose less energy than if the rock was solid. A spark chamber

could measure the energy of these rays and record the information on

tape.

The spark chamber was placed in a chamber (46 X 20 X 16 feet) in the

base of the pyramid. It appeared that something strange was going

on. The oscilloscopes showed a chaotic pattern and each time the

data was run through the computer, different results came out. No

one knew why this was happening. So, the results were inconclusive

and unfortunately they failed to find any hidden chambers and it

also raised doubts as to the efficacy of their methods. They did not

continue their work to explore the other pyramids or structures.

Others have tried to follow up on their research and methods to

discover hidden chambers.

In 1974 a team from Stanford University and the Ains Shams

University of Egypt, attempted to find hidden chambers using an

electromagnetic sounder. It used radio wave propagation to find

hidden chambers. Unfortunately, because of certain environmental

problems (for example moisture in the pyramid), this method did not

conclusively work either. This method for finding hidden chambers

was abandoned for the time being.

In 1986, two French architects used electronic detectors inside the

Great Pyramid to try to locate hollow areas. They found that below

the passageway leading to the Queen’s Chamber was another chamber 3

meters wide by 5 meters. They bore a 1” hole and found a cavity

filled with crystalline silica (sand). They were not allowed to do

any further digging. No entrances to these areas have yet been

found. This sand was analyzed and found to contain more than 99%

quartz that varied in size between 100-400 microns. This kind of

sand is known as musical sand since it makes a sound like a

whispering noise when it is blown or walked on. It appears that this

sand may come from El Tur in southern Sinai, which is several

hundred miles from the Great Pyramid. Why would this type of sand be

brought in from such a large distance and placed in a sealed off

chamber in the Great Pyramid?

In 1987, Japanese researchers from Waseda University used x-rays to

look for hollow spaces and chambers. They claimed to have discovered

a labyrinth of corridors and chambers inside the Great Pyramid. They

found a cavity about 1-½ meters under the horizontal passage to the

Queen’s Chamber and extending for almost 3.0 meters. They also

identified a cavity behind the western part of the northern wall of

the Queen’s Chamber. Other investigators have been unable to confirm

this but hopefully more scientific studies will be permitted to try

to verify these results.

In 1988 another Japanese team identified a cavity off the Queen’s

Chamber passageway, which was near to where the French team drilled

in 1986. A large cavity was also detected behind the Northwest wall

of the Queen’s Chamber. The Egyptian government stopped the project

and no further investigations were done.

In 1992, ground penetrating radar and microgravimetric measurements

were made in the Pit in the subterranean chamber and in the

horizontal passage connecting the bottom of the descending passage

with the subterranean chamber. A structure was detected under the

floor of the horizontal passage. Another structure was detected on

the western side of the passageway about 6 meters from the entrance

to the subterranean chamber. Soundings studies seem to indicate it

is a vertical shaft about 1.4 meters square and at 5 meters deep.

It is interesting to speculate about these chambers. What was their

purpose and do they still contain anything? It is hopeful that more

studies will be permitted in the near future.

Exploring the Air Shafts in the Queen’s Chamber

Up to 1872, no airshafts were discovered or suspected to exist in

the Queen’s Chamber. In that year, an engineer, Waynman Dixon

decided to look for airshafts in the Queen’s chamber. He reasoned

that if there were airshafts in the King’s chamber, why not in the

Queen’s Chamber as well. While looking at a section of the southern

wall where he thought an airshaft most likely would be located, he

noticed a crack. Using a hammer and chisel he quickly broke into an

airshaft measuring about 9 inches square going straight back into

the wall about 7 feet and then rising at an angle and disappearing

in the dark. Thus he discovered the southern airshaft into the

queen’s chamber.

Why was this airshaft never finished? It ended several inches inside

the wall of the Queen’s Chamber. He then went to the opposite side

or northern wall of the Queen’s chamber and did the same with a

hammer and chisel and found the other airshaft. It also went in

about 7 feet and then started to rise at an angle. Why these shafts

were not cut through into the chamber remains a mystery.

As earlier stated, we have known since the 1800’s that the airshafts

from the King’s chamber exit to the outside of the pyramid and the

actual exit points have been located. The airshafts in the Queen’s

Chamber are a different story. Where they terminate is not known. No

exit points on the surface of the pyramid have yet been found and it

has been assumed that these shafts end inside the pyramid. Many have

speculated that they end in a secret or hidden chamber.

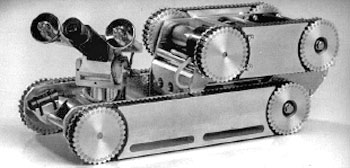

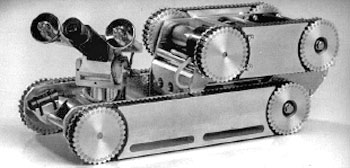

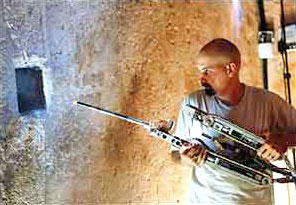

In the last decade we have developed the technology, which allows us

to explore this small shaft, measuring about 9 inches square. In

1993, Rudolf Gantenbrink from Germany used a miniature robot with a

camera to explore the southern airshafts leading out of the Queen’s

chamber. This robot was a very sophisticated device and its

manufacturing cost was about a quarter of a million dollars. It fits

into the opening of the airshaft and controlled by a cable attached

to it.

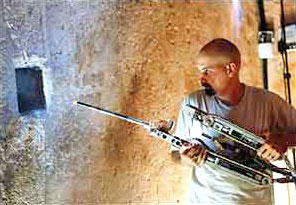

Rudolf Gantenbrink

and Upuaut

2

Thus, Gantenbrink and his staff positioned the small robot in the

small airshaft of the southern end of the Queen’s chamber and moved

it very slowly up the airshaft. A camera was mounted on the robot

and they could monitor its progress as it moved upwards. As the

robot proceeded up the airshaft, it sent back some of the first

pictures of what the inside of the airshaft looked like. It finally

came to the end of its journey after traveling about 200 feet into

the shaft.

The shaft did not lead to the outside but they saw at the

end of the shaft a small door with two small copper handles. It

appeared that there was a little gap under the door. There was not

enough room for the robot to go under or for the camera to see under

the door. Thus, another mystery had appeared. What if anything is

behind this door at the end of the airshaft?

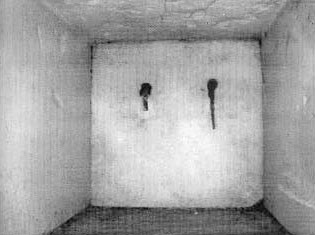

Door with metal handles filmed by Upuaut at the end of the southern

shaft

Gantenbrink had plans to pursue the exploration of the shaft but

unfortunately, possibly because of the politics, the Egyptian

authorities did not allow him to continue. His robot, Upuaut is

currently in the British Museum and nothing further came of his

exploration until many years later.

In 1995, Zahi Hawass, Director of the Giza Plateau in Egypt,

announced that there would be a follow up on the exploration of the

door leading to the alleged hidden chamber sometime in May of 1996.

He stated that an Egyptian, Dr Farouk El-Baz and a Canadian team

would conduct the exploration. This exploration never happened. Dr.

Hawass appeared on The Art Bell Show in January of 1998. He stated

that he hoped to explore the shaft and what was behind the door by

May of 1998. Again, nothing happened.

In late 1998, talks again surfaced of another group of researchers

who were developing a new and better robot to explore the airshafts.

In fact one of the rumors was that the new robot was designed and

would be operated by NASA scientists in late 1998 or1999. Nothing

further was ever heard of this rumor and no statements were made. It

was also rumored that during the millennium celebration in Egypt at

the Giza plateau, that the door at the end of the shaft would be

opened. This also never happened.

The big day finally came on

September 16, 2002 when millions all

over the world watched on TV. An exploration with a new robot was

approved by the Egyptian authorities and sent up the Southern

airshaft on this day. It was also mounted with a camera, a measuring

device, and a high-powered drill. This robot was special designed by

“iRobot” of Boston.

Pyramid Rover

by “iRobot” of

Boston

The measuring apparatus was used to try to

determine how thick the door was and to determine if a drill would

penetrate it so the camera could look inside. The measuring

apparatus found that the block was only 3 inches thick, suggesting

that it might be a door leading to another chamber.

The robot

drilled a small hole in the wall. When the camera looked through, it

appeared that there was a small empty chamber and another stone door

blocking the way. This next door appeared to be sealed and they did

not drill through this door. Millions viewed this event and many

were disappointed that they did not continue the exploration either

in that shaft or the other shaft.

Unknown to the general public, several days later, they sent the

robot up to explore the northern shaft. They discovered another door

blocking this shaft identical to the one in the southern shaft. The

doors in both shafts are 208 feet from the queen’s chamber. Up until

them, no one knew if the northern shaft extended to the north as far

as the southern shaft goes to the south. This newly discovered

northern shaft door appears to be similar to the door in the

southern shaft. It also has a pair of copper handles like the

southern door. No further exploration was done at that time.

Artifacts Found in the Great Pyramid

Since the1800’s several very interesting items have been found in

the Great Pyramid of Giza. In 1836, the explorer Colonel Vyse

discovered and removed a flat iron plate about 12” by 4” and 1/8”

thick from a joint in the masonry at the point where the southern

airshaft from the King’s chamber exits to the outside of the

pyramid. Engineers agree that this plate was left in the joint

during the building of the pyramid and could not have been inserted

afterwards. Colonel Vyse sent the plate to the British Museum. The

famous Sir Flinders Petrie examined the plate in 1881. He felt it

was genuine and stated “no reasonable doubt can therefore exist

about its being a really genuine piece”.

The following are the documents that were sent to the British Museum

to verify and certify the find.

The Iron plate, which Mr. Hill discovered in 1837 in an inner joint,

near the mouth of the southern air channel was sent to the British

Museum, with the following certificates:

measured 8 7/8 inches wide, by 9 ½ inches high.”

Fragment of the Iron Plate that was extracted from the core masonry

near the exit point of the southern shaft of the King’s Chamber in

1837

In 1989 Dr. Jones analyzed it in the mineral resources engineering

department at Imperial College and Dr. El Gayer in the department of

petroleum and mining at the Suez University. They used both chemical

and optical tests. One hypothesis was that the metal might have come

from a meteorite. It has been well documented that primitive and

Stone Age peoples have often used meteorite iron for implements,

such as tools and ritual objects. They were able to make crude iron

implements from the meteorite iron well before the Iron Age. In

fact, wrapped in King Tut’s mummy was a dagger made of meteorite

iron.

We can determine if this metal is meteorite or from the earth

by the nickel content of the Iron. Meteorite “iron” has a higher

value than the iron found on earth. The analysis of the metal plate

showed that it was not of meteoritic origin, since it contains only

a trace of nickel and not at the higher level of meteoritic iron.

Further analysis revealed that it had traces of gold on its surface,

indicating it maybe have once been gold plated. In their written

analysis, Drs. Jones and Gayer concluded the following:

“It is concluded, on the basis of the present investigation, that

the iron plate is very ancient. Furthermore, the metallurgical

evidence supports the archeological evidence, which suggests that

the plate was incorporated within the pyramid at the time that

structure was being built.”

As we mentioned, the finding of this iron plate may cause us to

change the date of the Iron Age by more than 2000 years. Drs. Jones

and Gayer thought this plate might be a fragment from a larger

piece, which was fitted over the mouth of the airshaft. Up to now,

this larger piece, of which the plate was a part, has not been

found.

Artifacts Found in the Queen’s chamber Airshafts

Waynman Dixon, the engineer who discovered the openings of the

Queen’s Chamber airshafts in 1872, also discovered some very

interesting objects in the northern Queen’s chamber airshaft. A

little ways up the airshaft, he found these three objects:

These objects were brought to England with

Dixon when he returned.

However, in a short period of time they had disappeared. Recently it

was found that they had remained in the hands of the Dixon family

and in the 1970’s were donated to the British Museum. They remained

there unknown until the 1990’s when they reappeared again. It is

interesting to note that the wood artifact was missing. This wood

could have been C14 dated and maybe given us the year of the

building of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

As mentioned above, in 1993 Rudolf Gantenbrink explored the southern

airshaft with his robot. He also sent the robot up the Northern

airshaft for a short distance beyond where Dixon found his

artifacts.

The robot discovered (on video film) two artifacts:

-

A metallic hook

-

A long piece of wood

Maybe this wood could be removed and Carbon14 dated.

Northern Shaft of the Queen’s Chamber showing the wood

Hopefully, we will not have to wait too long to continue the

exploration of the shafts in the Queen’s Chamber. What lies behind

the second door in the southern airshaft, and also the first door in

the northern airshaft, remains a mystery for now. It would also be

very important to remove some of the artifacts still remaining in

the Northern Air shaft for testing. Maybe a newer robot would have

the capabilities to remove these objects and even a sample of the

copper handles on the door. It appears from the photographs that

some of the copper has broken off and is on the ground by the door.

Maybe this can be retrieved and analyzed as well.

Many scientists are trying to develop other means of discovering

hidden chambers and passages in the Great Pyramid of Giza and other

monuments and structures. It is an exciting possibility that one

day, maybe a hidden chamber will be found and reveal to us

information about our past that we were not aware of. Also, we will

wait to see what is behind all those sealed doors in the Queen’s

Chamber airshafts.

|