|

by Ian Lawton

2002

from

SaturnianCosmology Website

High-Level Chambers

The particular circumstances of the Great Pyramid cause significant

complications for the pyramids-as-tombs theory. Although we have

seen that many of its features which some of the alternative camp

would have us believe are unique—its Grand Gallery, portcullis

arrangement, alignment to the cardinal points, and so on—are not,

the reason for this complication is its primary and genuinely unique

feature: the fact that it has chambers high up in its

superstructure.

Although we have seen that the Meidum and Dashur

Pyramids, and the Second Pyramid, have chambers which either butt

into or are entirely enclosed by the superstructure, they are all at

or near ground level. By contrast the Queen’s and King’s Chambers

lie at about one-fifth and two-fifths of the height of the Great

Pyramid respectively, and are accessed by a separate Ascending

Passage which branches off from the normal Descending Passage.

Before we look at the implications of this for the pyramids-as-tombs

theory, let us pause to consider a few general issues surrounding

this layout. The question which is always raised by the alternative

camp is: why did the builders go to so much trouble to implement

such a difficult design? In answer, we know that contemporary tomb

robbing was a major problem for these Old Kingdom kings, and at the

start of his reign Khufu would have seen that many of his

predecessors tombs had already been ransacked—including perhaps

those of his father and mother.

Having his architects design

ingenious methods of concealed burial was therefore a major priority

for a king who, above all else, needed to ensure that his body

remained intact so that his spirit could live on in peace in the

afterlife. The leading architects and masons themselves would by

this time have become some of the most influential men in ancient

Egyptian society, and would have been vying for the key posts in Khufu’s entourage by coming up with ever more ingenious designs for

his great monument. And while some of them would have been the

experienced men who worked on the various evolutions of Sneferu’s

Pyramids, others would have been young and bursting with new ideas.

All this sounds pretty reasonable to us. However Alford and others

raise another serious objection: Why did this process not continue

in the subsequent generations? This is a hard one to answer, and as

with so many of these issues requires primarily speculation, as

unsatisfactory as that may be. The main piece of pertinent evidence

we should consider is an analysis of the Great Pyramid by the French

engineer Jean Kerisel. He made a detailed survey of the edifice in

the early 1990’s, and argues that the construction method was

fatally flawed because the builders were attempting to use two types

of stone with substantially differing levels of compressibility:(1)

It is perfectly possible to construct a pyramid of a height of 150m

without incident in a homogenous material; the pyramid of Chephren

is there as a witness. Much more difficult is to introduce a large

internal space lined with rigid material within the pyramid; certain

precautions must then be taken; one cannot mix the “hard” and the

“soft” with impunity in something that is subject to strong

pressures…

During the raising of the pyramid, the superstructure of the

[King’s] chamber, surrounded by nummulitic limestone masonry which

contracted, emerged and efforts were concentrated on it: the

[granite] roof of the chamber and that of the first of the upper

floors fractured. Fine fractures of little depth at first, which

then enlarged and deepened until they crossed some of the beams…

When informed of the first cracks, they would have been worried;

this is proved by the fact that some of the fissures in the chamber

and in several places in the upper chambers were filled in. But

nobody could then penetrate into the upper chambers, as they were

now bordered on their east and west gables by nummulitic limestone

masonry. They therefore ordered a halt to the work in the central

part, and the digging of a pit that allowed access to these

chambers. And this [repair work] was done twice, since one finds

fillings in two different plasters.

These backward steps enable us to see the scale of the disaster:

support wedges in the worn-out roofs, the branches of a compass

formed by the chevron-shaped roof spreading 4cm to the east and 2cm

to the west. There is not really a more improper expression than

that of “relieving chambers”, so often used to describe what was

piled up above the King’s Chamber: on the contrary, they were

heavily overloaded and, moreover, warped…

Cheops then ordered a lighter construction of the upper part of the

pyramid, which recent gravimeter measurements show has a lesser

density. Were the worries of Cheops shared by the clergy and

dignitaries of his regime? Did the effort demanded seem

disproportionate to the result? And is it not the moment to admit

that the testimony of Herodotus concerning the exhaustion of the

people and their loathing for the pharaoh is not, perhaps, pure

fabrication?

The least that can be said is that the construction of the second

part of the pyramid knew some very important incidents. Finally, we

note that Cheop’s successors took advantage of the lesson, since

none of them ventured any more to insert a chamber of this type in

the middle of the bulk of his pyramid.

This analysis contradicts Petrie’s theory, which still has

widespread credibility amongst Egyptologists, that the cement

repairs were performed by the priests responsible for the

maintenance of the edifice after the Pyramid was constructed, as a

result of earthquakes; furthermore he suggests this is why the Well

Shaft was dug, from the bottom up. However in our view this latter

suggestion is entirely at odds with the known facts, as we will

shortly see. As a result, we find Kerisel’s analysis more

compelling—even though both alternatives provide an answer as to

when the passage to Davison’s Chamber was built, and why.

It is

further supported if we conduct a similar analysis of the Queen’s

Chamber: of course this had a pent rather than a flat roof, and one

might argue that the major stresses were taken by the King’s Chamber

above it anyway. But according to Kerisel’s theories one of the

major reasons why this chamber shows minimal signs of cracks would

be that its lining is made from the same material as the surrounding

core blocks—limestone. The question which immediately springs to

mind is why didn’t the subsequent generations of builders learn from

this and continue to build chambers in the superstructure, but

composed entirely of limestone? The answer is that they did not have

the benefit of this analysis.

Remember also that the effort involved

in lifting the 50 to 70 tonne granite monoliths which formed the

roofs of the King’s and Relieving Chambers was of an entirely

different order of magnitude from that of lifting the smaller and

lighter limestone blocks. This had never been tried before. And if

Kerisel is right, Khufu and his architects caused so much grief for

his builders that none of his successors wanted to repeat the

performance. After this step too far, the overwhelming urge to push

forward the design barriers probably came to a dramatic halt.

There are important additional implications if this theory is

correct. First, those who search ardently for additional chambers in

the superstructure of other pyramids—as at least one scientific team

has done in the Second Pyramid, as we will see later—are likely to

be in for a disappointment. And second, those who search for

additional chambers in the superstructure of the Great Pyramid

itself are also likely to be disappointed, albeit that the logic for

this is less secure.

Nevertheless, there is every indication that for a while size

remained important for Khufu’s successors. Although Djedefre’s

pyramid at Abu Roash was not planned on a particularly large scale,

there is reason to suppose he may have been something of a usurper

who may never have been assured of his position. In any case his

pyramid was unfinished, and his reign was short. Khafre, on the

other hand, built a monument almost equal in size to that of Khufu,

albeit that he made sure that only the roof of his upper chamber

poked into the superstructure.

And Nebka, who Lehner suggests came

next in line before Menkaure, seems to have planned a similarly huge

edifice at Zawiyet el-Aryan, although this was again substantially

incomplete due to his very short reign. Quite what it was that

persuaded Menkaure and all subsequent kings to build considerably

smaller pyramids remains a mystery. We can speculate that it was

either due to economic factors, or changes in religious emphasis, or

a combination of the two. But we cannot be sure. Does admitted

uncertainty on this point invalidate the pyramids-as-tombs theory?

Given the mass of other contextual evidence, we think not.

Empty Chambers?

The next issue that alternative researchers often raise is that no

funerary accoutrements have ever been discovered inside the Great

Pyramid, other than the empty and lidless coffer in the King’s

Chamber. We have already seen that contemporary looting was

widespread in the other pyramids, but is the same true here?

When Were the Lower Reaches First Breached?

The Classical historians provide plenty of circumstantial evidence

that the lower reaches of the Great Pyramid had been entered at

least by their time, which was long before Mamun. Even if it was not

particularly accessible in their day, as we have seen Herodotus

mentions underground chambers, and Pliny the “well”. Meanwhile

Strabo—although he appears not to have visited Giza personally—

mentions a “doorway” in the entrance (an issue we consider in detail

shortly), and in so doing reveals something of the interior (2)

At a moderate height in one of the sides is a stone, which may be

taken out; when that is removed, there is an oblique passage leading

to the tomb.

Only Diodorus’ account gives no clue that the interior might have

been entered before—strangely mentioning the entrance to the Second

but not that to the Great Pyramid, even though he may have actually

visited the Plateau. (3)

Although it is of course possible that these historians were only

relating information that had been passed down from the time of the

builders, we find this unlikely. And in any case there is hard

evidence that the edifice had been entered before Mamun came to the

Plateau, all of which we have already mentioned in passing: First,

Mamun reported torch marks on the ceiling of the Subterranean

Chamber. Second, Caviglia reported finding Latin characters on the

same ceiling; we cannot be sure when these were daubed, but we know

the Descending Passage had been blocked for some centuries before he

cleared it, so these could well date to classical times. Third,

Mamun reported being able to crawl back up the Descending Passage

right to the original entrance without undue effort, and since we

have postulated that it too would have been plugged for some

distance with sealing blocks, these must have been removed

previously.

Although this evidence strongly suggests that the lower reaches of

the edifice had been entered in antiquity, possibly shortly after it

was constructed and repeatedly thereafter, it does not prove that

the upper reaches were breached before Mamun’s time. Since it is

only this which could overwhelmingly prove that the burial chamber

was robbed—which would be why Mamun found it empty—and thereby

provide support for the pyramids-as-tombs theory even in relation to

the Great Pyramid, it is to this issue we must now turn.

When Were the Upper Reaches First Breached?

This is by far the most difficult element of the whole jigsaw of the

Plateau to piece together. It requires the analysis of a multitude

of different pieces of evidence, many of which conflict. Many

researchers from both camps tend to skip over the details,

especially those which do not fit their preferred explanation, and

in truth we were tempted to join them due to the complexity of the

analysis which must be undertaken. Nevertheless we must stick to our

guns and attempt to present all the evidence without being

selective, even if this makes the arguments more complex and leads

to a less definitive conclusion.

The reasons for the complexity are primarily twofold: first, the

uniqueness of the layout; and second, the lack of verifiable detail

in accounts of Mamun’s exploits.

We are of the opinion that it is

highly likely that Mamun was responsible for digging the intrusive

tunnel which provided a second entrance into the Pyramid—or possibly

even an exit to remove items that would not fit round the corner at

the junction of the Ascending and Descending Passages. (4) However,

it is far more complex to judge whether he was also responsible for

the tunnel which by-passes the granite plugs at the base of the

Ascending Passage. And there is another crucial factor which affects

our judgment: could the Well Shaft have been used to enter the

upper reaches in early antiquity?

Let us take these in reverse order, and examine the Well Shaft

first. In his The Great Pyramid, published in 1927, David Davidson

(who as we have seen was a supporter of the “encoded timeline”

theories promoted by Menzies, Smyth and Edgar) included a sketch

which suggested that the block which had originally sealed the upper

entrance to the shaft had been pushed out from below.

Others have

since relied on this analysis, but they are now in the minority.

Apart from the physical improbability of attempting to dislodge a well-cemented and sizeable block from below in a cramped space, a

close examination of the chisel marks on the topside of the blocks

which surround the upper entrance to the shaft reveals that it was chiselled out from above.(5) This is a piece of evidence we would

love to omit, because it would make this discussion a great deal

easier.

Many Egyptologists have suggested that the Upper Chambers

were plundered in antiquity by robbers who knew about the Well Shaft

and used it to gain access into the upper reaches, and this is a

nice simple theory which makes perfect sense if it was not for this

piece of evidence. To spell it out, if the block sealing the Well

Shaft was removed from above there can only be two explanations:

-

It is possible that the shaft was originally built in secret

without official sanction. The workers would have bribed the foreman

to allow them to build an escape route, but it would have to be kept

secret. The entrance would have been sealed off, but when the

plugging blocks had been released down the Ascending Passage they

would have chiselled up the block sealing the shaft and escaped.

However, there is no general precedent for the ancient Egyptian

kings deliberately entombing their workers alive along with them.

Consequently we must reluctantly turn to the alternative…

-

The shaft was discovered only after the tunnel which by-passes the

granite plugs in the Ascending Passage had been dug. Consequently

whoever dug this tunnel was indeed the first person to enter the

upper reaches of the edifice.

We cannot be sure of the accuracy of the accounts of

Mamun’s

exploration. It is therefore possible that he did find a body in the

King’s Chamber, and a lid on the sarcophagus, and various other

funerary ancillaries—as suggested by Hokm’s account. However, if the

pyramids-as-tombs theory is to remain vindicated in the Great

Pyramid, we must examine the possibility that Mamun was not

responsible for digging the by-pass tunnel. There are a number of

possibilities which might point to this being the case:

-

First, we have noted that the older accounts of

Mamun’s

explorations are unreliable. Because of this both omissions therefrom and statements therein can be used to argue for and

against any given point, with little solid justification. However it

is worth postulating that while most of the accounts talk about him

using fire and vinegar to tunnel the intrusive entrance, few of them

mention the circumstances of the tunneling to by-pass the plugs. Is

it reasonable to suggest that the circumstances of the “miraculous”

dislodging of the limestone block concealing the granite

plugs—without which piece of fortune Mamun could never have

discovered the Ascending Passage unless it was already

by-passed—were embellishments to make a better story, which have

grown to become part of pyramid folklore?

-

Second, we have already seen that in the Arab historian

Edrisi’s

first-hand account of entering the Pyramid he records having seen

what could only be hieroglyphs on the Queen’s Chamber ceiling. We

have also already noted that his accounts are accurate and detailed

in most respects. This is by no means definitive proof that the

chamber had been entered in antiquity, but it certainly adds to the

picture.

-

Third, a large portion of the corner of the coffer in the Kings

Chamber has been broken off. It is highly likely that this occurred

as a result of someone trying to prize off the lid—the original

existence of which is proved by some rarely mentioned evidence of

fittings (see Appendix II)—rather than through the petty efforts of

vandals or souvenir hunters. The implication of this is that either

Mamun did find a lid on the coffer, and almost certainly prized it

off himself, or someone else had been in there before him. Again,

not definitive proof, but the arguments are building up.

-

Fourth, there is similar rarely mentioned evidence that a “Bridge

Slab” originally spanned the gap in the floor between the Ascending

Passage and the Grand Gallery (this gap occasioned by the horizontal

passage leading off to the Queen’s Chamber), and also that the

portcullis’ in the King’s Antechamber were originally in place—

evidence that we will consider in detail shortly. None of the

accounts of Mamun’s exploration record him having to demolish these

obstacles. Is this simple omission, or had they already been

removed?

These points might start to swing the balance in favour of a

pre-Mamun by-passing of the plugs. But we must now look at a further

complicating issue: what happened to the debris resulting from the

digging of the by-pass tunnel? The standard accounts suggest that

Mamun explored the Subterranean Chamber first, then turned his

attention to by-passing the Ascending Passage—and that the rubble

from this operation was allowed to fall down the Descending Passage,

thereby blocking it until Caviglia cleared it. Vyse’s and other

contemporary reports of Caviglia’s work are likely to be more

reliable than much of the other evidence we are currently

considering, so we can assume that the Descending Passage was

blocked when he found it. But by what?

It is entirely possible that

this was primarily the debris from the post-Mamun stripping of the

casing stones, combined with the sand which would have blown in and

accumulated once the edifice was opened up by him. This in turn

allows for the possibility that the debris from the by-pass tunnel

was entirely separate, and— although if intruders dug the tunnel

they almost certainly would have let the debris fall down the

Descending Passage—it could have been cleared long before by

restorers. This in turn would have allowed the Subterranean Chamber

to be visited, as we are fairly certain it was, by travelers in

classical times.

Before attempting to draw any preliminary conclusions from all this,

there is one further piece of evidence which we must review, albeit

that once again it raises more questions than it answers.

The Denys of Telmahre Affair

Lehner, along with many others, quotes the observations of one

Denys

of Telmahre, described as a “Jacobite Patriarch of Antioch”, who

supposedly accompanied Mamun’s party to Giza and, furthermore,

recorded that the Great Pyramid was already open.(6) They therefore

suggest that Mamun did not dig the intrusive tunnels, only

rediscovered and possibly enlarged them. Of course if this were true

and as simple as it sounds, all our worries would be over. But,

alas, it is not. In fact these are gross over-simplifications.

Perusal of Vyse’s Operations reveals what Denys actually recorded.

The first is a translation provided by Latif, as follows:(7)

I have looked through an opening, fifty cubits deep, made in one of

those buildings [the Giza Pyramids], and I found that it was

constructed of wrought stones, disposed in regular layers.

This extract is backed up by a reproduction by Vyse, in French, of

Denys’ own account.(8) Both clearly indicate that what Denys did was

look into one of the pyramids on the Plateau—but he doesn’t say

which one. Furthermore, from his use of the word deep it would

appear that he was looking into a passage which went down, not in

horizontally. Finally, his description of “wrought stones disposed

in regular layers” seems to confirm that he was looking into one of

the original descending passages, not into the horizontal and forced

entrance in the Great Pyramid. Since we stick with our view that the

latter was forced by Mamun or a contemporary, logic dictates that

the original Descending Passage in the Great Pyramid was concealed

at this time. So Denys must have been looking into one of the

descending passages in either the Second or the Third Pyramid.

Unless we have picked up entirely the wrong element of Denys’

account, this tells us nothing whatsoever about the state of the

Great Pyramid at the time of Denys’ visit, and—even if it is true

that he accompanied Mamun—of the latter’s explorations.(9)

|

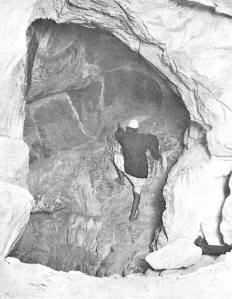

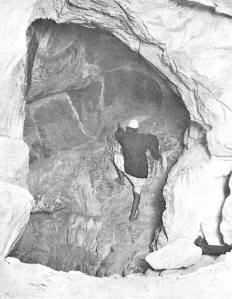

|

|

|

AL MAMOUN'S

CAVITY; showing the upper portion of the exposed west

side of the GRANITE PLUG which blocks the entrance of

the First Ascending Passage in the Great Pyramid.

. |

The upper

south end, and portion of the west side, of the GRANITE

PLUG which completely blocks the lower end of the First

Ascending Passage in the Great Pyramid of Gizeh; showing

two of the series of three great stones, hidden in the

masonry for three thousand years, and exposed by Caliph

Al Mamoun in the course of his excavations in the year

820 A.D. |

Lehner mentions another account, that of

Abu Szalt of Spain, which

he suggests is sober and trustworthy. In Lehner’s words: “He tells

of Mamun’s men uncovering an ascending passage. At its end was a

quadrangular chamber containing a sarcophagus.” This in itself does

not tell us much, but Lehner then adds what appears to be a direct

quote. (10)

The lid was forced open, but nothing was discovered excepting some

bones completely decayed by time.

At the time of writing we have been unable to check this intriguing

account further. In any case, whilst it may add support to the

pyramids-as-tombs theory, as with all other reports of this age it

cannot be regarded as definitive proof.

Buried Elsewhere?

For those of you who still believe that Mamun was the first to reach

the King’s Chamber and found an empty coffer, we present one final

alternative, proposed by Wheeler and others.(11) It is that, for

fear of defilers, Khufu was not buried in the Great Pyramid at all,

but elsewhere and in secret. Provided we accept the context that it

was always intended as a funerary edifice, this latter explanation

would still demand that he complete his pyramid, and conduct a false

burial therein—including the lowering of the portcullis’ and granite

plugs, and the incorporation of the Well Shaft to allow the last

workmen to escape. Clearly he was expected to erect a magnificent

pyramid, as were all kings at the time.

But the best way to preserve

the anonymity of his resting place, and ensure his body remained

intact to allow his spirit to continue in the afterlife, would be to

be buried in an unmarked and deep shaft tomb. If he did execute this

plan, it would have two likely preconditions: First, it would have

to be kept incredibly secret. Literally only one or two of his most

trusted advisers would have been informed. And second, given the

unparalleled complexity of the interior of his pyramid, he would

almost certainly have chosen this path only once the Great Pyramid’s

construction was either well under way or even nearing completion.

What could have led him Khufu to this drastic course of action? It

is possible that the original tomb of Hetepheres—his father’s wife

if not his mother—had been ransacked, possibly at Dashur; (for more

on Hetepheres’ reburial, see Appendix II). If this were the case,

almost certainly he himself ordered her re-burial in a deep unmarked

shaft next to his pyramid, although he may not have been told that

her mummy was already missing. Was this what forced him to change

his mind, if indeed he did? Who knows.

Wheeler in fact goes further with his analysis, arguing that a

number of factors point to the entire edifice being completed with a

minimum of detail, and with some elements left incomplete. He

singles out: (12)

-

The unfinished state of the Queen’s Chamber and of the passage

leading to it—both of which are valid observations but could be

explained by replanning.

-

The rough and apparently unfinished state of the exterior of the

King’s Chamber coffer—which ought to be the focal point of the

edifice. This is probably the most valid of his observations.

-

The fact that only three sealing plugs were used instead of the

full complement of 25. Again, a valid but not conclusive argument.

-

The supposed evidence that the three main portcullis’ were never

installed. On this point he is almost certainly mistaken, as we will

shortly see.

Whilst we have some sympathy with Wheeler’s extended argument, it

clearly also has some flaws. In any case we can disagree with this

extension without it affecting the validity of his basic “buried

elsewhere” proposition. Is there any other evidence which backs up

his basic theory? In fact, yes. Diodorus makes the following

observation: (13)

Although the kings [Chemis/Khufu and Cephres/Khafre] designed these

two for their sepulchers, yet it happened that neither of them were

there buried. For the people, being incensed at them by the reason

of the toil and labour they were put to, and the cruelty and

oppression of their kings, threatened to drag their carcasses out of

their graves, and pull them by piece-meal, and cast them to the

dogs; and therefore both of them upon their beds commanded their

servants to bury them in some obscure place.

Diodorus’ account is not the best by any means, but this observation

is a unique one—albeit that it links in with Herodotus’ general

comments regarding the unpopularity of both Khufu and Khafre. Could

it have some basis in truth? Many Egyptologists also suspect that,

for example, Djoser was buried in his “Southern Tomb” and not

underneath his pyramid.

It is possible that all these early kings decided to be buried

elsewhere.

J.P. Lepre in particular presents a compelling argument that all

early kings had two burial edifices, one in the north and one in the

south, to represent the duality of their reign over both Upper and

Lower Egypt. On this basis he suggests that the reason that so many

coffers have been found empty, even when sealed, is that the

pyramids in which they were found may have been merely cenotaphs

connected with ritual practices.

As a corollary he even suggests

that, since most of these edifices are relatively speaking in the

north, their real tombs may be found much farther to the south: in

fact he suggests the old “twin cities” of Abydos and nearby

Thinis

(the latter being the ancient capital of Upper Egypt before the

unification of the two lands by Menes) may hold a cache of hidden

rock-tombs or shaft graves of Old Kingdom kings similar to the New

Kingdom ones found more or less by accident in the Valley of the

Kings as late as the 1920’s. (14)

In our view the “burial elsewhere” theory is a perfectly valid

alternative regarding the Great Pyramid, and possibly others.

However it requires just as much speculation as the previous

interpretations of when the upper reaches of the Great Pyramid were

first breached. While we await further evidence which may one day

come to light to sway the balance one way or another, in the

meantime we leave you, the reader, to decide which is your preferred

solution. Indeed you may decide, like us, that both have their

merits and neither deserves to be singled out. This is not

woolly-minded, merely an acceptance that on a few issues more than

one theory has equal validity.

Security Features

We have already indicated that in order for us to be able to

evaluate how and when the Great Pyramid may have been breached, we

need to review the orthodox theories as to the security arrangements

for its unique interior. This might also help us to evaluate the

purpose of some of the more detailed features which might otherwise

be regarded as unexplained enigmas—such as the regularly cut

recesses in the Grand Gallery walls.

The Entrance

Starting at the outside, we have Strabo’s supposed report of a

hinged door-block. The original existence of this is normally taken

for granted, but—although this is a point rarely picked up by the

alternative camp—it begs the question as to why it would be

necessary if the pyramid was only to be used once, as a tomb, before

it was sealed up. The standard response is that it was required to

allow the priests to enter the building to perform maintenance and

inspections.

However this argument runs directly contrary to the

evidence which we have already reviewed, for example in relation to

the Second and Third Pyramids, that the descending passages were

sealed with blocks. Although we have no concrete evidence that this

was also true of the Great Pyramid’s Descending Passage, we should

ask ourselves why, if context is king, the Great Pyramid should have

been any different from its counterparts. Clearly the Ascending

Passage was sealed with blocks, so why not the Descending Passage

also?

Is there physical evidence for a hinged-block system? The casing

stones around the original entrance have now been stripped, as have

many of the core blocks behind them, so it is impossible to judge.

However the huge double gables over the “inner” entrance, albeit

that they were built for support rather than decoration, somehow do

not appear to us consistent with the idea of a small hinged door.

Meanwhile Egyptologists such as Petrie and more recently Lepre have

conducted detailed analysis’ of the way the “doors” might have

worked, based primarily on the fact that the Bent Pyramid’s western

entrance apparently shows signs of just such a system. (15) The

blocks on either side of the entrance are reported to contain

distinct sockets in which the hinges would have swiveled, while the

floor— although now filled in—originally contained a deep recess

which would have been necessary for the block to swivel inwards;

(this is Lepre’s reappraisal of Petrie’s theory, which suggested,

apparently incorrectly and based on Strabo’s original description,

that it would have swiveled outwards).

Lepre also suggests that the

Meidum Pyramid contains similar sockets. We can only say that we

have been unable to inspect these entrances for ourselves. But even

if Lepre’s analysis is correct, at least in relation to the western

entrance of the Bent Pyramid—which is unique in itself anyway—we are

inclined to think that it does not carry over to the monuments on

the Giza Plateau.

Let us now examine Strabo’s account in more detail. It is by far the

shortest and least detailed of those prepared in classical times.

What is more the translation of his work which is normally

reproduced is as follows:

“A stone that may be taken out, which

being raised up, there is a sloping passage”.(16)

However an

original translation of Strabo’s Geographica dating to 1857, which

we consulted and have already reproduced, merely says: “…a stone,

which may be taken out; when that is removed”—not “raised up”. The

translation of the original Greek is clearly important.

Edwards and Lehner both admit that if a hinged-door had existed in

Strabo’s time, it could only have been put in place long after the

edifice had first been violated. (17) We were prepared to write this

off as an unlikely theory which relies too heavily on Strabo’s

account until we considered the following. Whoever dug the intrusive

entrance tunnel—and in our view it is highly likely that this was

Mamun—was clearly unable to locate the original entrance.

Furthermore, unlike the situation at the Second Pyramid, in this

case the forced entry is below the real entry, so accumulated sand

and debris cannot be the solution as to why the explorers could not

locate it.

For this reason, at whatever time this tunnel was

created, the original entrance must have been cleverly concealed.

This view is supported by the fact that reports of Mamun’s

exploration do not mention him fighting his way through insects,

bats and their excreta in the various passages—a common feature of

future explorers’ accounts, which suggests that his entrance was the

first to open the edifice up to vast numbers of such creatures.

Since there is every reason to believe the edifice had been entered

long before this, the original entrance used by all previous

explorers cannot have been left open.

Therefore we can only surmise that someone—possibly Saite period

restorers—had either fitted a hinged-block, or had accurately

refitted the missing casing stones. The case for the former is

enhanced by the fact that it is likely that the interiors of all the

edifices were repeatedly entered at least in pre-Classical times,

and in accepting this inevitability the development of such an entry

mechanism may have proved less of an effort than continually

refitting the casing blocks. It may even be argued that the priests

at this time would have allowed restricted entry to the edifice for

the important, initiated or wealthy— in just the same way as is now

being proposed for the edifice to prevent it from rapid decline due

to the incursion of thousands of tourists every year.

A Dummy Chamber?

The next point we should consider about security is that some

Egyptologists have suggested that the Subterranean Chamber was

deliberately built as a decoy, to prevent robbers from searching for

the real chambers up in the superstructure. Given the emphasis that

was placed on security, this is at first sight a plausible theory.

However, we have already seen that there is persuasive evidence that

this chamber has such an unfinished appearance because it was

abandoned in favour of the higher chambers as part of a replanning

exercise. Furthermore, if it were built as a decoy they would surely

have finished it so it looked like a proper chamber. These two

theories are mutually exclusive, and we are minded to stick with the

latter.

The Plugging Blocks

We have already agreed with Vyse’s suggestion that the Descending

Passage was originally plugged with limestone sealing blocks,

perhaps as far as its junction with the Ascending Passage. Moving on

we have the granite plugs which block the bottom of this latter

passage. We know that these would have been concealed by an angled

limestone block in the roof of the Descending Passage, which would

have been indistinguishable from the rest of the ceiling. Three of

these blocks are still in position, and they are the ones that are by-passed by the additional intrusive tunnel. Two questions arise

concerning these blocks.

-

First, were they slid into place or built

in situ?

-

And second, how many of them were there originally?

Furthermore these two questions are inter-related.

The most convenient theory is that they were slid into place,

because this would explain the existence of the regular slots cut

into the side ramps of the Grand Gallery—which Borchardt surmised

were used to house wooden beams which held the plugs in place while

they were being stored therein. It has been suggested that these

blocks are such a tight fit in the Ascending Passage itself that

there is no way they could have been slid down without snagging, and

that consequently they must have been built in situ. However this is

not as valid an argument as it at first appears, for a number of

reasons:

-

First, Lepre produces some highly important and rarely publicized

measurements which show that the Ascending Passage is uniquely

tapered, unlike all the other original passages in the pyramids

which are always built with great precision to consistent

dimensions. (18) Where it emerges into the Grand Gallery it measures

53 inches high by 42 inches wide; half way down it measures 48 by

41½ inches; and at the bottom (where the three plugs are now) it

measures 47¼ by 38½ inches.

In the few places where the passage is

not worn away by visitors, it is clear that it too was originally

finished with great precision, so we must conclude that this taper

of 5¾ inches in height and 3½ inches in width over the 124 feet of

its length is deliberate. The clearance remains sufficiently small

that the blocks would still have been in grave danger of snagging as

they neared the bottom, but a number of researchers have suggested

that the process was assisted by a lubricating mortar—of which

traces have been found.

-

Second, the distance between the ramps on either side of the

Grand

Gallery is exactly the same as the width of the top of the Ascending

Passage, suggesting it was deliberately designed to hold the

plugging blocks.

-

Third, Noel F. Wheeler, the

Field Director of Reisner’s

Harvard-Boston Expedition, wrote a paper published in the periodical

Antiquity in 1935 which again provides rarely publicized evidence.

(19)

He noted that there are five pairs of holes in the walls at the

base of the Grand Gallery, in the “gap” between the end of the

Ascending Passage and the continuation of the sloping floor of the

Gallery—this gap occasioned by the branching off of the horizontal

passage which leads to the Queen’s Chamber. He argues that these

were used to locate wooden beams that supported a “Bridge Slab”

which would have provided a continuation of the sloping floor. It

would have been at least 17 feet long, thick enough to support the

plugs as they slid down, and would also have effectively sealed off

the passage to the Queen’s Chamber—which shows no signs of having

been itself sealed with plugs.

Although no traces of this slab have

ever been found—in our view because it was probably destroyed by

robbers in early antiquity, after which the debris would have been

cleared out by restorers—this would be a necessity for the “sliding

plugs” theory to work. In support of this theory, there are 5 inch

“lips” on each side of the gap against which the slab would have

rested.

-

Fourth, Borchardt’s replanning evidence regarding the change in

orientation of the blocks from which the Ascending Passage is formed

precludes the possibility that the plugging blocks were placed in

situ. Since he theorized that the lower section of the passage was

originally solid masonry which was subsequently carved out, the

plugs would still have had to be slid down it, albeit for a shorter

distance.

-

Fifth, Lehner notes that in the Bent Pyramid’s small satellite

there is a short ascending passage which may represent an admittedly

far smaller-scale prototype for that in the Great Pyramid. (20) At

the point where it increases in height from the normal few feet,

there is a notch in the wall which he believes may have been used to

locate a wooden chock which, when pulled away by rope, would have

released the plugging block or blocks it was supporting.

There is one additional feature of the Grand Gallery which we must

examine: on each side a groove—about 7 inches high and 1 inch

deep—has been cut into the third layer of corbelling along its

entire length. Lepre suggests that this was used to locate a wooden

platform, presumably accessed by a ladder at each end, which at this

height would still be 6 feet wide, along which the funeral cortege

would have progressed—thereby avoiding the plugging blocks housed

below. (21)

(Some Egyptologists have suggested that the blocks

themselves were housed up on this platform, with the cortege passing

below, but we find this an unlikely scenario which would require far

greater complexity in getting the plugs down again; in addition the

wooden boards might have had difficulty in supporting the weight of

the blocks).

In addition, at the top of the grooves there are rough

chisel marks running along their entire lengths, from which Lepre

argues that whatever was housed in the grooves was valuable to

robbers and well worth the effort of removing. He therefore surmises

that the platform may have comprised cedar panels inlaid with gold.

Although this platform would have been somewhat higher than appears

necessary, and although we are not entirely convinced by Lepre’s

explanation of the chisel marks, this theory appears the most

plausible so far put forward.

Even though they accept that a funeral procession would only involve

an inner wooden coffer while the granite one remained in situ, some

alternative researchers have still argued against this theory by

suggesting that this supposedly sombre and formal occasion could

hardly be expected to be conducted while effectively negotiating an

obstacle course. However we regard this argument as fatuous, since

the processions which had to negotiate the cramped space and steep

incline of the descending passages in all the other pyramids would

have faced equally awkward conditions.

All of this seems to us to point towards the “sliding plugs” theory

being the correct one. Furthermore it appears to offer a reasonable

explanation for the otherwise enigmatic features of the Grand

Gallery.

Although in no way would we wish to denigrate the exquisite design

and execution of this remarkable feature of the edifice, we are

forced to conclude that it had a primarily functional rather than

symbolic purpose.

We must now turn to the equally vexing question of how many blocks

were actually used to seal the Ascending Passage. Given our

preference for the “sliding plugs” theory, we know that there would

have been provision to house about 25 of them in the Grand Gallery.

We also know that the grooves for locating the chocks, and indeed

for the overhead walkway, run along the entire length. But does this

mean that this many were actually used? We know that the intrusive

tunnel at the bottom of the Ascending Passage only by-passes the

three which remain in situ.

We can see no reason for previous

intruders to have broken up a full 22 massive granite blocks from

the top down. After all, what would be their motivation to perform

such a mammoth task in the first place if they had already entered

the upper chambers, and in any case why would they leave the last

three in place? It is possible that additional limestone plugs were

used, so that whoever performed the tunneling got past the granite

blocks and then continued on through these softer plugs themselves.

However we find it more likely that only three blocks were ever

used.

Given that the Gallery was clearly designed to house so many more,

we must then ask why the change of plan came about, and indeed when.

After all, the decision would have to have been reached at the

latest before the roof of the Gallery was completed in order that

the chosen number of plugs could be lowered into it, and yet after

the first three corbels of the Gallery’s walls had been completed

with their various niches and grooves. As unsatisfactory as it is to

indulge in mere speculation, we can only suggest that it was decided

at this point that, in combination with the other security features

discussed in this section, three plugs would be enough.

This would

certainly have saved significant time and effort, notwithstanding

that short-cuts are not a regular feature of this edifice; (the

other alternative, as we have already seen, is that Khufu decided at

this point that he wanted to be buried elsewhere). Meanwhile we

should note that the chisel marks indicate that it must have been

decided that the possibly gold-inlaid walkway should still run the

entire length of the Gallery.

The Portcullis System

We have already noted that the granite-lined King’s Antechamber

contains four sets of slots in the side walls for portcullis’ to be

lowered into position. We have also noted that this is a feature

present in many of the other pyramids, although this particular

arrangement is more complex than most. Each of the three main sets

of slots is 3 feet deep and 21½ inches wide, while the northernmost

slots only reach down to the level of the passage roof.

Two granite

slabs are still in situ in the latter, but a significant space

remains above them. Since the west, south and east walls of the

Antechamber itself, and the passage, are also lined with granite, we

can assume that this was the material from which the portcullis’

would have been made. The whole of this section of the interior was

clearly intended to be extremely hard to break through.

Once again we must turn to the invaluable scholarship of Lepre to

assist our understanding of this mechanism. (22) He indicates that

there are three channels cut into the south wall of the antechamber,

each about 3½ inches wide, which would have been required in order

that the ropes used to lower the portcullis’ into place would not

snag between the slab and the wall. Although he points out that

there is some doubt over the oft-touted possibility that wooden

rollers may have been housed above the slots, around which the ropes

would have operated, he suggests that the slabs in the northernmost

slots would have acted as counterweights—thereby refuting the other

oft-touted suggestion that the uppermost of them is missing.

He also

indicates that from the rear or northern side of the upper

counterweight protrudes a semi-circular boss—although again he

points out that it does not seem to be properly designed to act as a

boss around which a rope could have been secured, and is forced to

leave its true function as a matter for further study.

It is often suggested that no fragment of the three missing

portcullis’ has ever been found, and from this many alternative

researchers—and even some Egyptologists—deduce that they were never

even fitted. In the first instance, the continued presence of the

counterweights— which are above the level of the passage and

therefore would not obstruct the progress of an intruder—suggests to

us that the portcullis,

’were originally in place but were broken up

by the early robbers. Again we would suggest that, as with the

“Bridge Slab”, the debris from this operation would have been

cleaned up by restorers. However, in addition to this evidence, Lepre produces a real coup de grace on the matter: he has matched

the four blocks of fractured granite found in and around the edifice

to the dimensions of the portcullis’. (23)

In brief, each of the main slabs would have been a minimum of 4 feet

high by 4 feet wide—probably more depending on the degree of overlap

into the slots—and most significantly about 21 inches thick (to

allow a tolerance of ½ inch in the slots). He examined the four

blocks—one lies near the pit in the Subterranean Chamber, another in

the niche in the west wall just before the entrance to this chamber,

another in the Grotto in the Well Shaft, and another outside the

original entrance—and established that whilst they were all less

than 4 feet in height and width, they were all 21 inches thick!

(Note that there is a loose block of granite in the King’s Chamber,

but this is known to come from the floor thereof and was therefore

omitted from the analysis.)

As if this were not sufficient evidence,

he found that three of the four blocks have 3½ inch holes drilled in

them—in fact the one in the pit has two, and the one near the

entrance three. Furthermore, the holes in the latter are spaced 6½

inches apart. So he established that not only do the holes have the

same diameter as the channels for the ropes in the south wall of the

Antechamber, but they are also spaced the same distance apart.

Although Lepre is unable to provide a foolproof explanation as to

how these four fragments ended up in their present locations—he

suggests a variety of high jinks by early visitors to the

monument—nevertheless this strikes us as pretty convincing evidence

that these are indeed fragments of the original portcullis’.

The Well Shaft

It is appropriate now to return to the question of who dug the

enigmatic Well Shaft, and why. It has been suggested that it was dug

by the earliest robbers, who needed a mechanism to get into the

upper reaches of the edifice, and who knew the internal layout

sufficiently to dig upwards from the bottom and still find the base

of the Grand Gallery. However there are a number of factors which

suggest that this analysis is incorrect.

-

First, it is clear that the

top end of the shaft was originally sealed by a block which fitted

into the ramp in the west wall of the Grand Gallery, and clearly

mere robbers would not have concealed their tunnel in this way.

-

Second, it would be infinitely harder to excavate this tunnel

upwards rather than downwards—it would require platforms, and the

fragments of rock would continually fall into the workers’ faces.

-

Third, at the bottom the shaft continues a little below the level of

the Descending Passage, which it would not do if it had been dug

from there in the first place.

-

Fourth, the top third of the shaft

runs through the superstructure (the remainder through the bedrock),

and the uppermost section of this was not tunneled through the

masonry but deliberately built into it during construction; (24)

(this would also support the replanning theory, in that the lower

part of this top third would have been tunneled through the masonry

after it was decided to abandon the Subterranean Chamber).

-

Fifth, any intruder who had discovered the upper reaches of the

edifice by by-passing the granite plugs would have had no reason to

then dig this additional shaft.

It is therefore almost certain that the

Well Shaft was dug at the

time the edifice was constructed. It is likely that its purpose was

to provide the workers responsible for sliding the granite plugs

into place at the foot of the Ascending Passage with a means of

escape; after all, the distance involved and the weight of the plugs

(even if there were only three) meant they would not have been able

to release the chocks from beneath the passage “remotely” by rope.

We can surmise that once the plugs had been released, they would

have let themselves down into the shaft; and that once they were all

out they would probably have hidden the bottom of the shaft with an

appropriate block so that it would not be discovered.

It is perhaps enigmatic that the tunnel was designed to travel for

such a long distance—several hundred feet—in a vertical and then

southerly direction, when it could have been made far shorter either

by traveling vertically down, or even better by sloping in a

northerly direction at a respectable distance underneath the

Ascending Passage. However Maragioglio and Rinaldi suggest that it

was dug to provide additional ventilation for the Descending Passage

and the Subterranean Chamber during their construction, and as an

ancillary motive this might explain the lengthy course.

Conclusion

We have considered a great deal of detailed analysis in this paper,

not all of it conclusive, but to reach a conclusion we must once

again stand back from the detail and remind ourselves of the

context. We have all the ancillary evidence from the other pyramids.

We have the fact that all the pyramids, including the Great Pyramid,

were clearly the focal point of funerary complexes.

We have the fact

that the Great Pyramid cannot be removed from the chronology. And we

have the fact that it was sealed with plugs and portcullis’ just

like all the others, that its coffer was designed to take a lid, and

that the Grand Gallery and its slots and grooves, and the Well

Shaft, all had specific functions in a funerary edifice. Therefore,

despite the detailed areas of uncertainty that remain, we stand by

the theory that the Great Pyramid was primarily designed as a tomb

for king Khufu.

The only other aspect of the Great Pyramid that we have not

revisited in this analysis is the enigmatic “air” shafts in the

King’s and Queen’s Chambers, which we consider in a later chapter.

We believe that these almost certainly do have a symbolic rather

than a practical function, but we are also of the view that

acceptance of the important role played by symbolism and ritual in

the pyramids is not mutually exclusive with the tombs theory.

|