|

1 - The Host of Heaven

In the beginning

God created the Heaven and the Earth.

The very concept of a beginning of all things is basic to modern

astronomy and astrophysics. The statement that there was a void and

chaos before there was order conforms to the very latest theories

that chaos, not permanent stability, rules the universe. And then

there is the statement about the bolt of light that began the

process of creation.

Was this a reference to the Big Bang, the theory according to which

the universe was created from a primordial explosion, a burst of

energy in the form of light, that sent the matter from which stars

and planets and rocks and human beings are formed flying in all

directions and creating the wonders we see in the heavens and on

Earth? Some scientists, inspired by the insights of our most

inspiring source, have thought so. But then, how did ancient Man

know the Big Bang theory so long ago? Or was this biblical tale the

description of matters closer to home, of how our own little planet

Earth and the heavenly zone called the Firmament, or “hammered-out

bracelet,” were formed? Indeed, how did ancient Man come to have a

cosmogony at all? How much did he really know, and how did he know

it?

It is only appropriate that we begin the quest for answers

where the events began to unfold—in the heavens; where also,

from time immemorial, Man has felt that his origins, higher

values—God, if you will—are to be found. As thrilling as

discoveries made by the use of microscopes are, it is what

telescopes enable us to see that fills us with the realization of

the grandeur of nature and the universe. Of all recent advances,

the most impressive have undoubtedly been the discoveries in the

heavens surrounding our planet.

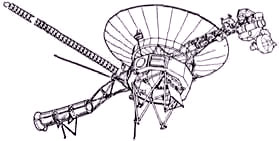

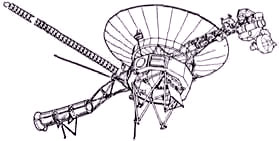

Figure 1

And what staggering advances they have been! In a mere few decades we Earthlings have

soared off the face of our planet; roamed Earth’s skies hundreds of

miles above its surface; landed on its solitary satellite, the Moon;

and sent an array of unmanned spacecraft to probe our celestial

neighbors, discovering vibrant and active worlds dazzling in their

colors, features, makeup, satellites, rings. For the first time,

perhaps, we can grasp the meaning and feel the scope of the

Psalmist’s words:

The heavens bespeak the glory of the Lord and the vault of heaven

reveals His handiwork.

A fantastic era of planetary exploration came to a magnificent

climax when, in August 1989, the unmanned spacecraft designated

Voyager 2 flew by distant Neptune and sent back to Earth pictures

and other data. Weighing just about a ton but ingeniously packed

with television cameras, sensing and measuring equipment, a power

source based on nuclear decay, transmitting antennas, and tiny

computers (Fig. 1), it sent back whisper-like pulses that required

more than four hours to reach Earth even at the speed of light.

On

Earth the pulses were captured by an array of radiotelescopes that

form the Deep Space Network of the U.S. National Aeronautics and

Space Administration (NASA); then the faint signals were translated

by electronic wizardry into photographs, charts, and other forms of

data at the sophisticated facilities of the Jet Propulsion The Host

of Heaven 5 Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, which managed

the project for NASA.

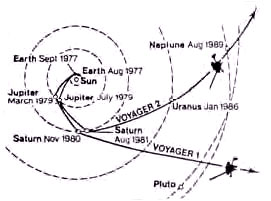

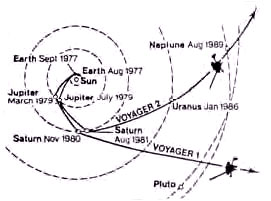

Launched in August 1977, twelve years before this final mission—the

visit to Neptune—was accomplished. Voyager 2 and its companion.

Voyager I, were originally intended to reach and scan only Jupiter

and Saturn and augment data obtained earlier about those two gaseous

giants by the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 unmanned spacecraft. But

with remarkable ingenuity and skill, the JPL scientists and

technicians took advantage of a rare alignment of the outer planets

and, using the gravitational forces of these planets as

“slingshots,” managed to thrust Voyager 2 first from Saturn to

Uranus and then from Uranus to Neptune (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

Thus it was that for several days at the end of August 1989,

headlines concerning another world pushed aside the usual news of

armed conflicts, political upheavals, sports results, and market

reports that make up Mankind’s daily fare. For a few days the world

we call Earth took time out to watch another world; we, Earthlings,

were glued to our television sets, thrilled by close-up pictures of

another planet, the one we call Neptune.

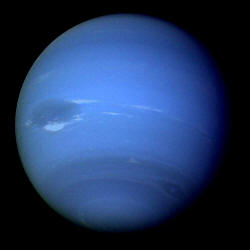

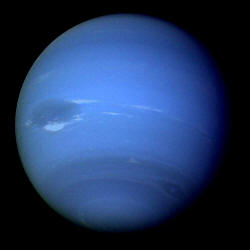

As the dazzling images of an aquamarine globe appeared on our

television screens, the commentators stressed repeatedly that this

was the first time that Man on Earth had ever really been able to

see this planet, which even with the best Earth-based telescopes is

visible only as a dimly lit spot in the darkness of space almost

three billion miles from us. They reminded the viewers that Neptune

was discovered only in 1846, after perturbations in the orbit of the

somewhat nearer planet Uranus indicated the existence of another

celestial body beyond it.

They reminded us that no one before

that—neither Sir Isaac Newton nor Johannes Kepler, who between them

discovered and laid down the laws of celestial motion in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; neither Copernicus, who in the

sixteenth century determined that the Sun, not the Earth, was in the

center of our planetary system, nor Galileo, who a century later

used a telescope to announce that Jupiter had four moons—no great

astronomer until the mid-nineteenth century and certainly no one in

earlier times knew of Neptune. And thus not only the average TV

viewer but the astronomers themselves were about to see what had

been unseen before—it would be the first time we would learn the

true hues and makeup of Neptune.

But two months before the August encounter, I had written an article

for a number of U. S., European, and South American monthlies

contradicting these long-held notions: Neptune was known in

antiquity, I wrote; and the discoveries that were about to be made

would only confirm ancient knowledge. Neptune, I predicted, would be

blue-green, watery, and have patches the color of “swamplike

vegetation”!

The electronic signals from Voyager 2 confirmed all that and more.

They revealed a beautiful blue-green, aquamarine planet embraced by

an atmosphere of helium, hydrogen, and methane gases, swept by

swirling, high-velocity winds that make Earth’s hurricanes look

timid. Below this atmosphere there appear mysterious giant “smudges”

whose coloration is sometimes darker blue and sometimes greenish

yellow, perhaps depending on the angle at which sunlight strikes

them. As expected, the atmospheric and surface temperatures are

below freezing, but unexpectedly Neptune was found to emit heat that

emanates from within the planet.

Contrary to the previous The Host

of Heaven 7 consideration of Neptune as being a “gaseous” planet, it

was determined by Voyager 2 to have a rocky core above which there

floats, in the words of the JPL scientists, “a slurry mixture of

water ice.” This watery layer, circling the rocky core as the planet

revolves in its sixteen-hour day, acts as a dynamo that creates a

sizable magnetic field.

This beautiful planet (below image) was found to be

encircled by several rings made up of boulders, rocks, and dust and

is orbited by at least eight satellites, or moons. Of the latter,

the largest, Triton, proved no less spectacular than its planetary

master.

Voyager 2 confirmed the retrograde motion of this small

celestial body (almost the size of Earth’s Moon): it orbits Neptune

in a direction opposite to that of the coursing of Neptune and all

other known planets in our Solar System, not anticlockwise as they

do but clockwise. Besides its very existence, its approximate size,

and its retrograde motion, astronomers knew nothing else of Triton.

Voyager 2 revealed it to be a “blue moon,” an appearance resulting

from methane in Triton’s atmosphere.

The surface of Triton showed

through the thin atmosphere—a pinkish gray surface with rugged,

mountainous features on one side and smooth, almost craterless

features on the other side. Close-up pictures suggested recent

volcanic activity but of a very odd kind: what the active, hot

interior of this celestial body spews out is not molten lava but

jets of slushy ice. Even preliminary assessments indicated that

Triton had flowing water in its past, quite possibly even lakes that

may have existed on the surface until relatively recent times, in

geological terms.

The astronomers had no immediate explanation for

“double-tracked ridge lines” that run straight for hundreds of miles

and, at one or even two points, intersect at what appears to be

right angles, suggesting rectangular areas (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

The discoveries thus fully confirmed my prediction:

-

Neptune

is indeed blue-green

-

it is made up in great part of water

-

it does have patches whose coloration looks like “swamp-like

vegetation”

This last tantalizing aspect may bespeak more

than a color code if the full implication of the discoveries on

Triton is taken into consideration: there, “darker patches with

brighter halos” have suggested to the scientists of NASA the

existence

of “deep pools of organic sludge.” Bob Davis reported from Pasadena to

The Wall Street Journal that Triton, whose

atmosphere contains as much nitrogen as Earth’s, may be spewing out

from its active volcanoes not only gases and water ice but also

‘”organic material, carbon-based compounds which apparently coat

parts of Triton.”

Such gratifying and overwhelming corroboration of my prediction was

not the result of a mere lucky guess. It goes back to 1976 when

The

12th Planet, my first book in The Earth Chronicles series, was

published. Basing my conclusions on millennia-old Sumerian texts, I

had asked rhetorically:

“When we probe Neptune someday, will we

discover that its persistent association with waters is due to the

watery swamps” that had once been seen there?

This was published, and obviously written, a year before Voyager 2

was even launched and was restated by me in an article two months

before the Neptune encounter. How could I be so sure, on the eve of

Voyager’s encounter with Neptune, that my 1976 prediction would be

corroborated—how dared I take the chance that my predictions would

be disproved within weeks after submitting my article? My certainty

was based on what happened in January 1986, when Voyager 2 flew by

the planet Uranus.

Although somewhat closer to us—Uranus is “only” about two billion

miles away—it lies so far beyond Saturn that it cannot be seen from

Earth with the naked eye. It was discovered in 1781 by Frederick

Wilhelm Herschel, a musician turned amateur astronomer, only after

the telescope was perfected. At the time of its discovery and to

this day, Uranus has been hailed as the first planet we known in

antiquity to be discovered in modern times; for, it has been held,

the ancient peoples knew of and venerated the Sun, the Moon, and

only five planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn), which

they believed moved around the Earth in the “vault of heaven”;

nothing could be seen or known beyond Saturn.

But the very evidence gathered by Voyager 2 at Uranus proved the

opposite: that at one time a certain ancient people did know about

Uranus, and about Neptune, and even about the more-distant

Pluto!

Plate A

Scientists are still analyzing the photographs and data from

Uranus and its amazing moons, seeking answers to endless

puzzles. Why does Uranus lie on its side, as though it was hit by

another large celestial object in a collision? Why do its winds blow

in a retrograde direction, contrary to what is normal in the Solar

System? Why is its temperature on the side that is hidden from the

Sun the same as on the side facing the Sun?

And what shaped the unusual features and formations on some

of the Uranian moons? Especially intriguing is the moon called

Miranda, “one of the most enigmatic objects in the Solar System,” in the words of

NASA’s astronomers, where an elevated,

flattened-out plateau is delineated by 100-mile-long escarpments

that form a right angle (a feature nicknamed “the Chevron” by the

astronomers), and where, on both sides of this plateau, there appear

elliptical features that look like racetracks ploughed over by

concentric furrows (Plate A and Fig. 4).

Figure 4

Two phenomena, however,

stand out as the major discoveries regarding Uranus, distinguishing

it from other planets. One is its color. With the aid of Earth-based

telescopes and unmanned spacecraft we have become familiar with the graybrown of Mercury, the sulphur-colored haze that envelops Venus,

the reddish Mars, the multihued red-brown-yellow Jupiter and Saturn.

But as the breathtaking images of Uranus began to appear on television screens in January 1986, its most striking

feature was its greenish blue color—a color totally different from

that of all the previous planets seen (see Uranus below).

The other different and unexpected finding had to do with what

Uranus is made of. Defying earlier assumptions by astronomers that

Uranus is a totally “gaseous” planet like the giants Jupiter and

Saturn, it was found by Voyager 2 to be covered not by gases but by

water; not just a sheet of frozen ice on its surface but an ocean of

water. A gaseous atmosphere, it was found, indeed enshrouds the

planet; but below it there churns an immense layer—6,000 miles

thick!—of “super-heated water, its temperature as high as 8,000

degrees Fahrenheit” (in the words of JPL analysts). This layer of

liquid, hot water surrounds a molten rocky core where radioactive

elements (or other, unknown processes) produce the immense internal

heat.

As the images of Uranus grew bigger on the TV screen the closer

Voyager 2 neared the planet, the moderator at the Jet Propulsion

Laboratory drew attention to its unusual green-blue color. I could

not help cry out loud,

"Oh, my God, it is exactly as the Sumerians

had described it!”

I hurried to my study, picked up a copy of The

12th Planet, and with unsteady hands looked up page 269 (in the Avon

paperback edition). I read again and again the lines quoting the

ancient texts. Yes, there was no doubt: though they had no

telescopes, the Sumerians had described Uranus as MASH.SIG, a term

which I had translated “bright greenish.”

A few days later came the results of the analysis of Voyager 2’s

data, and the Sumerian reference to water on Uranus was also

corroborated. Indeed, there appeared to be water all over the place:

as reported on a wrap-up program on the television series NOVA (‘The

Planet That Got Knocked on Its Side”), “Voyager 2 found that all the

moons of Uranus are made up of rock and ordinary water ice”. This

abundance, or even the mere presence, of water on the supposed

“gaseous” planets and their satellites at the edges of the Solar

System was totally unexpected.

Yet here we had the evidence, presented in The 12th Planet, that in

their texts from millennia ago the ancient Sumerians had not only

known of the existence of Uranus but had accurately described it as

greenish blue and watery!

What did all that mean? It meant that in 1986 modern science did not

discover what had been unknown; rather, it rediscovered and caught

up with ancient knowledge. It was, therefore, because of that 1986

corroboration of my 1976 writings and thus of the veracity of the

Sumerian texts that I felt confident enough to predict, on the eve

of the Voyager 2 encounter with Neptune, what it would discover

there.

The Voyager 2 flybys of Uranus and Neptune had thus confirmed not

only ancient knowledge regarding the very existence of these two

outer planets but also crucial details regarding them. The 1989

flyby of Neptune provided still more corroboration of the ancient

texts. In them, Neptune was listed before Uranus, as would be

expected of someone who is coming into the Solar System and sees

first Pluto, then Neptune, and then Uranus. In these texts or

planetary lists Uranus was called Kakkab shanamma, “Planet Which Is

the Double” of Neptune.

The Voyager 2 data goes far to uphold this

ancient notion. Uranus is indeed a look-alike of Neptune in size,

color, and watery content; both planets are encircled by rings and

orbited by a multitude of satellites, or moons. An unexpected

similarity has been found regarding the two planets’ magnetic

fields: both have an unusually extreme inclination relative to the

planets’ axes of rotation—58 degrees on Uranus, 50 degrees on

Neptune.

“Neptune appears to be almost a magnetic twin of Uranus,”

John Noble Wilford reported in The New York Times.

The two planets are also similar in the lengths of their days: each about sixteen to seventeen hours long. The ferocious winds on

Neptune and the water ice slurry layer on its surface attest to the

great internal heat it generates, like that of Uranus. In fact, the

reports from JPL state that initial temperature readings indicated

that,

“Neptune’s temperatures are similar to those of Uranus, which

is more than a billion miles closer to the Sun.”

Therefore, the

scientists assumed “that Neptune somehow is generating more of its

internal heat than Uranus does”—somehow compensating for its greater

distance from the Sun to attain the same temperatures as Uranus

generates, resulting in similar temperatures on both planets—and

thus adding one more feature “to the size and other characteristics

that make Uranus a near twin of Neptune.”

“Planet which is the

double,” the Sumerians said of Uranus in comparing it to Neptune.

“Size and other characteristics that make

Uranus a near twin of Neptune,” NASA’s scientists announced. Not

only the described characteristics but even the terminology—“planet

which is the double,” “a near twin of Neptune”—is similar. But one

statement, the Sumerian one, was made circa 4,000 B.C., and the

other, by NASA, in AD. 1989, nearly 6,000 years later. . . .

In the case of these two distant planets, it seems that modern

science has only caught up with ancient knowledge. It sounds

incredible, but the facts ought to speak for themselves. Moreover,

this is just the first of a series of scientific discoveries in the

years since The 12th Planet was published that corroborate its

findings in one instance after another.

Those who have read my books (The Stairway to Heaven,

The Wars of

Gods and Men, and

The Lost Realms followed the first one) know that

they are based, first and foremost, on the knowledge bequeathed to

us by the Sumerians. Theirs was the first known civilization.

Appearing suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere some 6,000 years

ago, it is credited with virtually all the “firsts” of a high

civilization: inventions and innovations, concepts and beliefs,

which form the foundation of our own Western culture and indeed of

all other civilizations and cultures throughout the Earth. The wheel

and animal-drawn vehicles, boats for rivers and ships for seas, the

kiln and the brick, high-rise buildings, writing and schools and

scribes, laws and judges and juries, kingship and citizens’

councils, music and dance and art, medicine and chemistry, weaving

and textiles, religion and priesthoods and temples—they all began

there, in Sumer, a country in the southern part of today’s Iraq,

located in ancient Mesopotamia.

Above all, knowledge of mathematics

and astronomy began there. Indeed, all the basic elements of modern

astronomy are of Sumerian origin: the concept of a celestial sphere,

of a horizon and a zenith, of the circle’s division into 360

degrees, of a celestial band in which the planets orbit the Sun, of

grouping stars into constellations and giving them the names and

pictorial images that we call the zodiac, of applying the number 12

to this zodiac and to the divisions of time, and of devising a

calendar that has been the basis of calendars to this very day. All

that and much, much more began in Sumer.

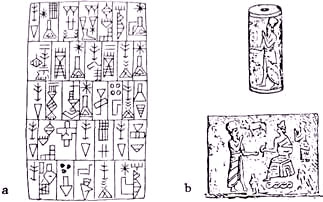

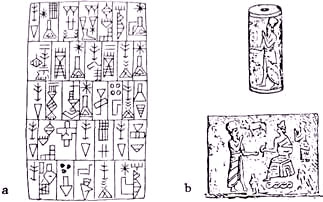

Figure 5

The Sumerians recorded their commercial and legal transactions,

their tales and their histories, on clay tablets (Fig. 5a); they

drew their illustrations on cylinder seals on which the depiction

was carved in reverse, as a negative, that appeared as a positive

when the seal was rolled on wet clay (Fig. 5b). In the ruins of

Sumerian cities excavated by archaeologists in the past century and

a half, hundreds, if not thousands, of the texts and illustrations

that were found dealt with astronomy. Among them are lists of stars

and constellations in their correct heavenly locations and manuals

for observing the rising and setting of stars and planets.

There are

texts specifically dealing with the Solar System. There are texts

among the unearthed tablets that list the planets orbiting the Sun

in their correct order; one text even gives the distances between

the planets. And there are illustrations on cylinder seals depicting

the Solar System, as the one shown in Plate B that is at least 4,500

years old and that is now kept in the Near Eastern Section of the

State Museum in East Berlin, catalogued under number VA/243.

Plate B

If we sketch the illustration appearing in the upper left-hand

comer of the Sumerian depiction (Fig. 6a) we see a complete

Solar System in which the Sun (not Earth!) is in the center,

orbited by all the planets we know of today. This becomes clear when

we draw these known planets around the Sun in their correct relative

sizes and order (Fig. 6b). The similarity between the ancient

depiction and the current one is striking; it leaves no doubt that

the twinlike Uranus and Neptune were known in antiquity.

Fig. 6

The Sumerian depiction also reveals, however, some differences.

These are not artist’s errors or misinformation; on the contrary,

the differences—two of them—are very significant. The first

difference concerns Pluto. It has a very odd orbit—too inclined to

the common plane (called the Ecliptic) in which the planets orbit

the Sun, and so elliptical that Pluto sometimes (as at present and

until 1999) finds itself not farther but closer to the Sun than

Neptune. Astronomers have therefore speculated, ever since its

discovery in 1930, that Pluto was originally a satellite of another

planet; the usual assumption is that it was a moon of Neptune that

“somehow”—no one can figure out how—got torn away from its

attachment to Neptune and attained its independent (though bizarre)

orbit around the Sun.

This is confirmed by the ancient depiction, but with a significant

difference. In the Sumerian depiction Pluto is shown

not near Neptune but between Saturn and Uranus. And Sumerian

cosmological texts, with which we shall deal at length,

relate that Pluto was a satellite of Saturn that was let loose to

eventually attain its own “destiny”—its independent orbit around the

Sun.

The ancient explanation regarding the origin of Pluto reveals not

just factual knowledge but also great sophistication in matters

celestial. It involves an understanding of the complex forces that

have shaped the Solar System, as well as the development of astrophysical theories by which moons can become

planets or planets in the making can fail and remain moons. Pluto,

according to Sumerian cosmogony, made it; our Moon, which was in the

process of becoming an independent planet, was prevented by

celestial events from attaining the independent status.

Modern astronomers moved from speculation to the conviction that

such a process has indeed occurred in our Solar System only after

observations by the Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft determined in the

past decade that

Titan, the largest moon of Saturn, was a

planet-in-the-making whose detachment from Saturn was not completed.

The discoveries at Neptune reinforced the opposite speculation

regarding Triton, Neptune’s moon that is just 400 miles smaller in

diameter than Earth’s Moon. Its peculiar orbit, its volcanism, and

other unexpected features have suggested to the JPL scientists, in

the words of the Voyager project’s chief scientist Edward Stone,

that,

“Triton may have been an object sailing through the Solar

System several billion years ago when it strayed too close to

Neptune, came under its gravitational influence and started orbiting

the planet.”

How far is this hypothesis from the Sumerian notion that planetary

moons could become planets, shift celestial positions, or fail to

attain independent orbits? Indeed, as we continue to expound the

Sumerian cosmogony, it will become evident that not only is much of

modern discovery merely a rediscovery of ancient knowledge but that

ancient knowledge offered explanations for many phenomena that

modern science has yet to figure out.

Even at the outset, before the rest of the evidence in support of

this statement is presented, the question inevitably arises:

How on Earth could the Sumerians have known all that so long ago, at

the dawn of civilization?

The answer lies in the second difference between the Sumerian

depiction of the Solar System (Fig. 6a) and our present knowledge of

it (Fig. 6b). It is the inclusion of a large planet in the empty

space between Mars and Jupiter. We are not aware of any such planet;

but the Sumerian cosmological, astronomical, and historical texts

insist that there indeed exists one more planet in our Solar

System—its twelfth member: they included the

Sun, the Moon (which they counted as a celestial body in its own

right for reasons stated in the texts), and ten, not nine, planets.

It was the realization that a planet the Sumerian texts called

NIBIRU (“Planet of the Crossing”) was neither Mars nor Jupiter, as

some scholars have debated, but another planet that passes between

them every 3,600 years that gave rise to my first book’s title, The

12th Planet—the planet which is the “twelfth member” of the Solar

System (although technically it is, as a planet, only the tenth).

It was from that planet, the Sumerian texts repeatedly and

persistently stated, that

the ANUNNAKI came to Earth. The term

literally means “Those Who from Heaven to Earth Came.” They are

spoken of in the Bible as the Anakim, and in Chapter 6 of Genesis

are also called

Nefilim, which in Hebrew means the same thing:

Those

Who Have Come Down, from the Heavens to Earth.

And it was from the Anunnaki, the Sumerians explained—as though they

had anticipated our questions—that they had learnt all they knew.

The advanced knowledge we find in Sumerian texts is thus, in effect,

knowledge that was possessed by the Anunnaki who had come from Nibiru; and theirs must have been a very advanced civilization,

because as I have surmised from the Sumerian texts, the Anunnaki

came to Earth about 445,000 years ago. Way back then they could

already travel in space. Their vast elliptical orbit made a

loop—this is the exact translation of the Sumerian term—around all

the outer planets, acting as a moving observatory from which the

Anunnaki could investigate all those planets. No wonder that what we

are discovering now was already known in Sumerian times.

Why anyone would bother to come to this speck of matter we call

Earth, not by accident, not by chance, not once but repeatedly,

every 3,600 years, is a question the Sumerian texts have answered.

On their planet Nibiru, the Anunnaki/Nefilim were facing a situation

we on Earth may also soon face: ecological deterioration was making

life increasingly impossible. There was a need to protect their

dwindling atmosphere, and the only solution seemed to be to suspend

gold particles above it, as a shield. (Windows on American

spacecraft, for example, are coated with a thin layer of gold to

shield the astronauts from radiation).

This

rare metal had been discovered by the Anunnaki on what they called

the Seventh Planet (counting from the outside inward), and they

launched Mission Earth to obtain it. At first they tried to obtain

it effortlessly, from the waters of the Persian Gulf; but when that

failed, they embarked on toilsome mining operations in southeastern

Africa. Some 300,000 years ago, the Anunnaki assigned to the African

mines mutinied. It was then that the chief scientist and the chief

medical officer of the Anunnaki used genetic manipulation and

in-vitro fertilization techniques to create “primitive workers”—the

first Homo sapiens to take over the backbreaking toil in the gold

mines.

The Sumerian texts that describe all these events and their

condensed version in the Book of Genesis have been extensively dealt

with in The 12th Planet. The scientific aspects of those

developments and of the techniques employed by the Anunnaki are the

subject of this book. Modern science, it will be shown, is blazing

an amazing track of scientific advances—but the road to the future

is replete with signposts, knowledge, and advances from the past.

The Anunnaki, it will be shown, have been there before; and as the

relationship between them and the beings they had created changed,

as they decided to give Mankind civilization, they imparted to us

some of their knowledge and the ability to make our own scientific

advances.

Among the scientific advances that will be discussed in

the ensuing chapters will also be the mounting evidence for the

existence of Nibiru. If it were not for The 12th Planet, the

discovery of Nibiru would be a great event in astronomy but no more

significant for our daily lives than, say, the discovery in 1930 of

Pluto. It was nice to learn that the Solar System has one more

planet “out there,” and it would be equally gratifying to confirm

that the planetary count is not nine but ten; that would especially

please astrologers, who need twelve celestial bodies and not just

eleven for the twelve houses of the zodiac.

But after the publication of The 12th Planet and the evidence

therein—which has not been refuted since its first printing in

1976—and the evidence provided by scientific advances since then,

the discovery of Nibiru cannot remain just a matter involving

textbooks on astronomy. If what I have written is so— if, in other words, the Sumerians were correct

in what they were recording—the discovery of Nibiru would mean not

only that there is one more planet out there but that there is Life

out there. Moreover, it would confirm that there are intelligent

beings out there—people who were so advanced that, almost half a

million years ago, they could travel in space; people who were

coming and going between their planet and Earth every 3,600 years.

It is who is out there on Nibiru, and not just its existence, that

is bound to shake existing political, religious, social, economic,

and military orders on Earth. What will the repercussions be

when—not if—Nibiru is found?

It is a question, believe it or not, that is already being pondered.

GOLD MINING—HOW LONG AGO?

Is there evidence that mining took place, in southern Africa, during

the Old Stone Age? Archaeological studies indicate that it indeed

was so.

Realizing that sites of abandoned ancient mines may indicate where

gold could be found, South Africa’s leading mining corporation, the

Anglo-American Corporation, in the 1970s engaged archaeologists to

look for such ancient mines. Published reports (in the corporation’s

journal Optima) detail the discovery in Swaziland and other sites in

South Africa of extensive mining areas with shafts to depths of

fifty feet. Stone objects and charcoal remains established dates of

35,000, 46,000, and 60,000 B.C. for these sites. The archaeologists

and anthropologists who joined in dating the finds believed that

mining technology was used in southern Africa “during much of the

period subsequent to 100,000 B.C.”

In September 1988, a team of international physicists came to South

Africa to verify the age of human habitats in Swaziland and

Zululand. The most modern techniques indicated an age of 80,000 to

115,000 years. Regarding the most ancient gold mines of Monotapa in

southern Zimbabwe, Zulu legends hold that they were worked by,

“artificially produced flesh and blood slaves created by the First

People.”

These slaves, the Zulu legends recount, “went into battle

with the Ape-Man” when “the great war star appeared in the sky” (see

Indaba My Children, by the Zulu medicine man

Credo Vusamazulu Mutwa).

Back to Contents

|