|

2 - IT CAME FROM

OUTER SPACE

“It was Voyager [project] that

focused our attention on the importance of collisions,”

acknowledged Edward Stone of the California Institute of

Technology (Caltech), the chief scientist of the Voyager

program.

“The cosmic crashes were potent sculptors of the Solar

System.”

The Sumerians made clear, 6,000 years

earlier, the very same fact. Central to their cosmogony, world view,

and religion was a cataclysmic event that they called the Celestial

Battle. It was an event to which references were made in

miscellaneous Sumerian texts, hymns, and proverbs—just as we find in

the Bible’s books of Psalms, Proverbs, Job, and various others. But

the Sumerians also described the event in detail, step by step, in a

long text that required seven tablets. Of its Sumerian original only

fragments and quotations have been found; the mostly complete text

has reached us in the Akkadian language, the language of the

Assyrians and Babylonians who followed the Sumerians in Mesopotamia.

The text deals with the formation of the Solar System prior to the

Celestial Battle and even more so with the nature, causes, and

results of that awesome collision. And, with a single cosmogonic

premise, it explains puzzles that still baffle our astronomers and

astrophysicists. Even more important, whenever these modern

scientists have come upon a satisfactory answer—it fits and

corroborates the Sumerian one!

Until the Voyager discoveries, the prevailing scientific viewpoint

considered the Solar System as we see it today as the way it had

taken shape soon after its beginning, formed by immutable laws of

celestial motion and the force of gravity.

There have been oddballs, to be sure—meteorites that come

from somewhere and collide with the stable members of the

Solar System, pockmarking them with craters, and comets that zoom

about in greatly elongated orbits, appearing from somewhere and

disappearing, it seems, to nowhere. But these examples of cosmic

debris, it has been assumed, go back to the very beginning of the

Solar System, some 4.5 billion years ago, and are pieces of

planetary matter that failed to be incorporated into the planets or

their moons and rings. A little more baffling has been the asteroid

belt, a band of rocks that forms an orbiting chain between Mars and

Jupiter. According to Bode’s law, an empirical rule that explains

why the planets formed where they did, there should have been a

planet, at least twice the size of Earth, between Mars and Jupiter.

Is the orbiting debris of the asteroid belt the remains of such a

planet?

The affirmative answer is plagued by two problems: the total

amount of matter in the asteroid belt does not add up to the

mass of such a planet, and there is no plausible explanation

for what might have caused the breakup of such a hypothetical

planet; if a celestial collision—when, with what, and why?

The scientists had no answer.

The realization that there had to be one or more major collisions

that changed the Solar System from its initial form became

inescapable after the Uranus flyby in 1986, as Dr. Stone has

admitted. That Uranus was lilted on its side was already known from

telescopic and other instrumental observations even before the

Voyager encounter. But was it formed that way from the very

beginning, or did some external force—a forceful collision or

encounter with another major celestial body—bring about the tilting?

The answer had to be provided by the closeup examination of the

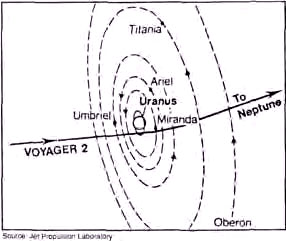

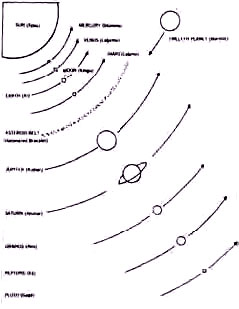

moons of Uranus by Voyager 2. The fact that these moons swirl around

the equator of Uranus in its tilted position—forming, all together,

a kind of bull’s-eye facing the Sun (Fig. 7)—made scientists wonder

whether these moons were there at the time of the tilting event, or

whether they formed after the event, perhaps from matter thrown out

by the force of the collision that tilted Uranus.

Figure 7

The theoretical basis for the answer was enunciated, prior to the

encounter with Uranus, among others by Dr. Christian Veillet of the

French Centre d’Etudes et des Recherches Geodynamiques. If the moons

formed at the same time as Uranus, the celestial “raw material” from

which they agglomerated should have condensed the heavier matter

nearer the planet; there should be more of heavier, rocky material

and thinner ice coats on the inner moons and a lighter combination

of materials (more water ice, less rocks) on the outer moons. By the

same principle of the distribution of material in the Solar System—a

larger proportion of heavier matter nearer the Sun, more of the

lighter matter (in a “gaseous” state) farther out—the moons of the

more distant Uranus should be proportionately lighter than those of

the nearer Saturn.

But the findings revealed a situation contrary to these

expectations. In the comprehensive summary reports on the Uranus

encounter, published in Science, July 4, 1986, a team of forty

scientists concluded that the densities of the Uranus moons (except

for that of the moon Miranda)’ ‘are significantly heavier than those

of the icy satellites of Saturn.” Likewise, the Voyager 2 data

showed—again contrary to what “should have

been”—that the two larger inner moons of Uranus, Ariel and

Umbriel,

are lighter in composition (thick, icy layers; small, rocky cores)

than the outer moons Titania and Oberon, which were discovered to be

made mostly of heavy rocky material and had only thin coats of ice.

These findings by Voyager 2 were not the only clues suggesting that

the moons of Uranus were not formed at the same time as the planet

itself but rather some lime later, in unusual circumstances. Another

discovery that puzzled the scientists was that the rings of Uranus

were pitch-black, “blacker than coal dust,” presumably composed of

“carbon-rich material, a sort of primordial tar scavenged from outer

space” (the emphasis is mine). These dark rings, warped, tilted, and

“bizarrely elliptical,” were quite unlike the symmetrical bracelets

of icy particles circling Saturn. Pitch-black also were six of the

new moonlets discovered at Uranus, some acting as “shepherds” for

the rings.

The obvious conclusion was that the rings and moonlets

were formed from the debris of a “violent event in Uranus’s past.”

Assistant project scientist at JPL Ellis Miner stated it in simpler

words:

“A likely possibility is that an interloper from outside the

Uranus system came in and struck a once larger moon sufficiently

hard to have fractured it.”

The theory of a catastrophic celestial

collision as the event that could explain all the odd phenomena on

Uranus and its moons and rings was further strengthened by the

discovery that the boulder-size black debris that forms the Uranus

rings circles the planet once every eight hours—a speed that is

twice the speed of the planet’s own revolution around its axis. This

raises the question, how was this much-higher speed imparted to the

debris in the rings?

Based on all the preceding data, the probability of a celestial

collision emerged as the only plausible answer.

“We must take into

account the strong possibility that satellite formation conditions

were affected by the event that created Uranus’s large obliquity,”

the forty-strong team of scientists stated.

In simpler words, it

means that in all probability the moons in question were created as

a result of the collision that knocked Uranus on its side. In press

conferences the NASA scientists were more audacious.

“A collision

with something the size of Earth, traveling at about 40,000 miles

per hour, could have done it,” they

said, speculating that it probably happened about four billion years

ago.

Astronomer Garry Hunt of the Imperial College, London, summed it up

in seven words:

“Uranus took an almighty bang early on.”

But neither in the verbal briefings nor in the long written reports

was an attempt made to suggest what the “something” was, where it

had come from, and how it happened to collide with, or bang into,

Uranus.

For those answers, we will have to go back to the Sumerians....

Before we turn from knowledge acquired in the late 1970s and 1980s

to what was known 6,000 years earlier, one more aspect of the puzzle

should be looked into: Are the oddities at Neptune the result of

collisions, or ‘ ‘bangs,” unrelated to those of Uranus—or were they

all the result of a single catastrophic event that affected all the

outer planets?

Before the Voyager 2 flyby of Neptune, the planet was known to have

only two satellites, Nereid and Triton. Nereid was found to have a

peculiar orbit: it was unusually tilted compared with the planet’s

equatorial plane (as much as 28 degrees) and was very

eccentric—orbiting the planet not in a near-circular path but in a

very elongated one, which takes the moon as far as six million miles

from Neptune and as close as one million miles to the planet.

Nereid, although of a size that by planetary-formation rules should

be spherical, has an odd shape like that of a twisted doughnut. It

also is bright on one side and pitch-black on the other.

All these

peculiarities have led Martha W. Schaefer and Bradley E. Schaefer,

in a major study on the subject published in Nature magazine (June

2, 1987) to conclude that,

“Nereid accreted into a moon around

Neptune or another planet and that both it and Triton were knocked

into their peculiar orbits by some large body or planet.”

“Imagine,”

Brad Schaefer noted, “that at one time Neptune had an ordinary

satellite system like that of Jupiter or Saturn; then some massive

body comes into the system and perturbs things a lot.”

The dark material that shows up on one side of Nereid could be

explained in one of two ways—but both require a collision in the scenario. Either an impact on one side of the

satellite swept off an existing darker layer there, uncovering

lighter material below the surface, or the dark matter belonged to

the impacting body and “went splat on one side of Nereid.” That the

latter possibility is the more plausible is suggested by the

discovery, announced by the JPL team on August 29, 1989, that all

the new satellites (six more) found by Voyager 2 at Neptune “are

very dark” and “all have irregular shapes,” even the moon designated

1989N1, whose size normally would have made it spherical.

The theories regarding Triton and its elongated and retrograde

(clockwise) orbit around Neptune also call for a collision event.

Writing in the highly prestigious magazine Science on the eve of the

Voyager 2 encounter with Neptune, a team of Caltech scientists (P.

Goldberg, N. Murray. P. Y. Longaretti, and D. Banfield) postulated

that,

“Triton was captured from a heliocentric orbit”—from an orbit

around the Sun—“as a result of a collision with what was then one of

Neptune’s regular satellites.”

In this scenario the original small

Neptune satellite “would have been devoured by Triton,” but the

force of the collision would have been such that it dissipated

enough of Triton’s orbital energy to slow it down and be captured by

Neptune’s gravity.

Another theory, according to which Triton was an

original satellite of Neptune, was shown by this study to be faulty

and unable to withstand critical analysis. The data collected by

Voyager 2 from the actual flyby of Triton supported this theoretical

conclusion. It also was in accord with other studies (as by David

Stevenson of Caltech) that showed that Triton’s internal heat and

surface features could be explained only in terms of a collision in

which Triton was captured into orbit around Neptune.

“Where did these impacting bodies come from?” rhetorically asked

Gene Shoemaker, one of NASA’s scientists, on the NOVA television

program.

But the question was left without an answer. Unanswered too

was the question of whether the cataclysms at Uranus and Neptune

were aspects of a single event or were unconnected incidents.

It is not ironic but gratifying to find that the answers to all

these puzzles were provided by the ancient Sumerian texts and that all the data discovered or confirmed by

the Voyager flights uphold and corroborate the Sumerian information

and my presentation and interpretation thereof in The 12th Planet.

The Sumerian texts speak of a single but comprehensive event. Their

texts explain more than what modern astronomers have been trying to

explain regarding the outer planets. The ancient texts also explain

matters closer to home, such as the origin of the Earth and its

Moon, of the Asteroid Belt and the comets. The texts then go on to

relate a tale that combines the credo of the Creationists with the

theory of Evolution, a tale that offers a more successful

explanation than either modern conception of what happened on Earth

and how Man and his civilization came about.

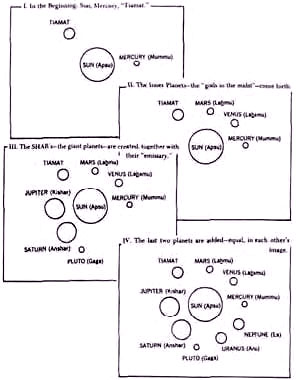

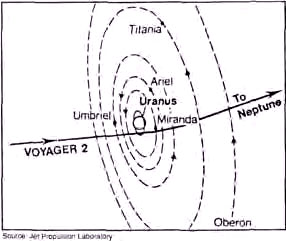

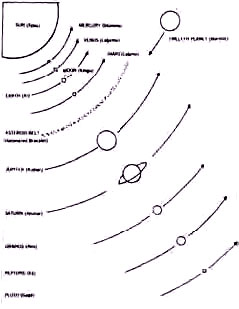

It all began, the Sumerian texts relate, when the Solar System was

still young.

The Sun (APSU in the Sumerian texts, meaning “One Who

Exists from the Beginning”), its little companion MUM. MU (“One Who

Was Born,” our Mercury) and farther away TI.AMAT (“Maiden of Life”)

were the first members of the Solar System; it gradually expanded by

the “birth” of three planetary pairs, the planets we call Venus and

Mars between Mummu and Tiamat, the giant pair Jupiter and Saturn (to

use their modern names) beyond Tiamat, and Uranus and Neptune

farther out (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

Into this original Solar System, still unstable soon after its

formation (I estimated the time about four billion years ago), an

Invader appeared. The Sumerians called it NIBIRU; the Babylonians

renamed it Marduk in honor of their national god. It appeared from

outer space, from “the Deep,” in the words of the ancient text. But

as it approached the outer planets of our Solar System, it began to

be drawn into it. As expected, the first outer planet to attract

Nibiru with its gravitational pull was Neptune—E.A (“He Whose House

Is Water”) in Sumerian. “He who begot him was Ea,” the ancient text

explained.

Nibiru/Marduk itself was a sight to behold; alluring, sparkling,

lofty, lordly are some of the adjectives used to describe

it. Sparks and flashes bolted from it to Neptune and Uranus as

it passed near them. It might have arrived with its own satellites

already orbiting it, or it might have acquired some as a result

of the gravitational pull of the outer planets. The ancient text

speaks of its “perfect members. . .difficult to perceive”—“four were his eyes, four were his ears.”

As it passed near Ea/Neptune, Nibiru/Marduk’s side began to bulge

“as though he had a second head.” Was it then that the bulge was

torn away to become Neptune’s moon Triton?

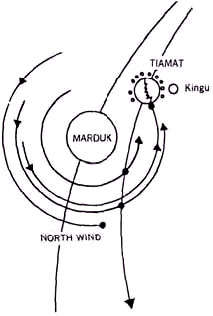

One aspect that speaks strongly for this is the fact that

Nibiru/Marduk entered the Solar System in a retrograde (clockwise)

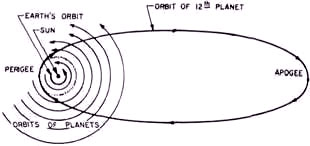

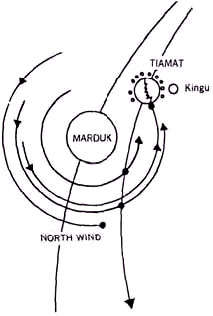

orbit, counter to that of the other planets (Fig. 9).

Figure 9

Only

this Sumerian detail, according to which the invading planet was

moving counter to the orbital motion of all the other planets, can

explain the retrograde motion of Triton, the highly elliptical

orbits of other satellites and comets, and the other major events

that we have yet to tackle.

More satellites were created as Nibiru/Marduk passed by Anu/Uranus.

Describing this passing of Uranus, the text states that “Anu brought

forth and begot the four winds”—as clear a reference as one could

hope for to the four major moons of Uranus that were formed, we now

know, only during the collision that tilted Uranus. At the same time

we learn from a later passage in the ancient text that Nibiru/Marduk

himself gained three satellites as a result of this encounter.

Although the Sumerian texts describe how, after its eventual capture

into solar orbit, Nibiru/Marduk revisited the outer planets and

eventually shaped them into the system as we know it today, the very

first encounter already explains the various puzzles that modern

astronomy faced or still faces regarding Neptune, Uranus, their

moons, and their rings.

Past Neptune and Uranus, Nibiru/Marduk was

drawn even more into the midst of the planetary system as it reached

the immense gravitational pulls of Saturn (AN.SHAR, “Foremost of the

Heavens”) and Jupiter (KI.SHAR, “Foremost of the Firm Lands”). As

Nibiru/Marduk “approached and stood as though

in combat” near Anshar/Saturn, the two planets “kissed their lips.”

It was then that the “destiny,” the orbital path, of Nibiru/Marduk

was changed forever. It was also then that the chief satellite of

Saturn, GA.GA (the eventual Pluto), was pulled away in the direction

of Mars and Venus—a direction possible only by the retrograde force

of Nibiru/Marduk. Making a vast elliptical orbit, Gaga eventually

returned to the outermost reaches of the Solar System.

There it

“addressed” Neptune and Uranus as it passed their orbits on the

swing back. It was the beginning of the process by which Gaga was to

become our Pluto, with its inclined and peculiar orbit that

sometimes takes it between Neptune and Uranus. The new “destiny,” or

orbital path, of Nibiru/Marduk was now irrevocably set toward the

olden planet Tiamat. At that time, relatively early in the formation

of the Solar System, it was marked by instability, especially (we

learn from the text) in the region of Tiamat. While other planets

nearby were still wobbling in their orbits, Tiamat was pulled in

many directions by the two giants beyond her and the two smaller

planets between her and the Sun.

One result was the tearing off her,

or the gathering around her, of a “host” of satellites “furious with

rage,” in the poetic language of the text (named by scholars the

Epic of Creation). These satellites, “roaring monsters,” were

“clothed with terror” and “crowned with halos,” swirling furiously

about and orbiting as though they were “celestial gods”—planets.

Most dangerous to the stability or safety of the other planets was

Tiamat’s “leader of the host,” a large satellite that grew to almost

planetary size and was about to attain its independent “destiny”—its

own orbit around the Sun. Tiamat “cast a spell for him, to sit among

the celestial gods she exalted him.” It was called in Sumerian

KIN.GU—“Great Emissary.” Now the text raised the curtain on the

unfolding drama; I have recounted it, step by step, in

The 12th

Planet. As in a Greek tragedy, the ensuing “celestial battle” was

unavoidable as gravitational and magnetic forces came inexorably

into play, leading to the collision between the oncoming Nibiru/Marduk

with its seven satellites (“winds” in the ancient text) and Tiamat

and its “host” of eleven satellites headed by Kingu.

Figure 10

Although they were headed on a collision course,

Tiamat

orbiting counterclockwise and Nibiru/Marduk clockwise, the

two planets did not collide—a fact of cardinal astronomical

importance. It was the satellites, or “winds,” (literal Sumerian

meaning: “Those that are by the side”) of Nibiru/Marduk that smashed

into Tiatnat and collided with her satellites.

In the first such encounter (Fig. 10),

the first phase of the

Celestial Battle,

The four winds he stationed

that nothing of her could escape:

The South Wind, the North Wind,

the East Wind, the West Wind.

Close to his side he held the net,

the gift of his grandfather Anu who brought forth the Evil Wind,

the

Whirlwind and the Hurricane. . . .

He sent forth the winds which he had created, the seven of them; to

trouble Tiamat within they rose up behind him.

These “winds,” or satellites, of Nibiru/Marduk,

“the seven of them,”

were the principal “weapons” with which Tiamat

was attacked in the

first phase of the Celestial Battle (Fig. 10).

But the invading planet had other “weapons” too:

In front of him he set the lightning,

with a blazing flame he filled his body;

He then made a net to enfold Tiamat therein. . . .

A fearsome halo his head was turbaned.

He was wrapped with awesome terror as with a cloak. As the two

planets and their hosts of satellites came close enough for Nibiru/Marduk

to “scan the inside of Tiamat” and ‘ ‘perceive the scheme of Kingu,”

Nibiru/ Marduk attacked Tiamat with his “net” (magnetic field?) to

“enfold her,” shooting at the old planet immense bolts of

electricity (“divine lightnings”). Tiamat “was filled with

brilliance”—slowing down, heating up, “becoming distended.” Wide

gaps opened in its crust, perhaps emitting steam and volcanic

matter. Into one widening fissure Nibiru/Marduk thrust one of its

main satellites, the one called “Evil Wind.” It tore Tiamat’s

“belly, cut through her insides, splitting her heart.”

Besides splitting up Tiamat and “extinguishing her life,” the first

encounter sealed the fate of the moonlets orbiting her—all except

the planetlike Kingu. Caught in the “net”—the magnetic and

gravitational pull—of Nibiru/Marduk, “shattered, broken up,” the

members of the “band of Tiamat” were thrown off their previous

course and forced into new orbital paths in the opposite direction:

“Trembling with fear, they turned their backs about.”

Thus were the comets created—thus, we learn from a 6,000-year-old

text, did the comets obtain their greatly elliptical and retrograde

orbits. As to Kingu, Tiamat’s principal satellite, the text informs

us that in that first phase of the celestial collision Kingu was

just deprived of its almost-independent orbit. Nibiru/Marduk took

away from him his “destiny.”

Nibiru/ Marduk made Kingu into a

DUG.GA.E, “a mass of lifeIt Came from Outer Space 35 less clay,”

devoid of atmosphere, waters and radioactive matter and shrunken in

size; and “with fetters bound him,” to remain in orbit around the

battered Tiamal. Having vanquished Tiamat, Nibiru/Marduk sailed on

on his new “destiny.” The Sumerian text leaves no doubt that the

erstwhile invader orbited the Sun:

He crossed the heavens and surveyed the regions, and Apsu’s quarter

he measured;

The Lord the dimensions of the Apsu measured.

Having circled the Sun

(Apsu),

Nibiru/Marduk continued into distant space.

But now, caught

forever in solar orbit, it had to turn back.

On his return round,

Ea/Neptune was there to greet him

and Anshar/Saturn hailed his

victory.

Then his new orbital path returned him

to the scene of the

Celestial Battle, “turned back to Tiamat whom he had bound.”

The

Lord paused to view her lifeless body.

To divide the monster he then artfully planned.

Then, as a mussel, he split her into two parts. With this act the

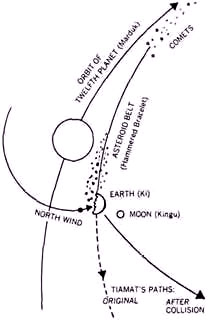

creation of “the heaven” reached its final stage, and the creation

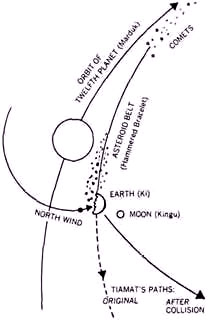

of Earth and its Moon began. First the new impacts broke Tiamat into

two halves. The upper part, her “skull,” was struck by the Nibiru/Marduk

satellite called North Wind; the blow carried it, and with it Kingu,

“to places that have been unknown”—to a brand-new orbit where there

had not been a planet before. The Earth and our Moon were created

(Fig. 11)!

The other half of Tiamat was smashed by the impacts into bits and

pieces.

This lower half, her “tail,” was “hammered together”

to

become a “bracelet” in the heavens:

Locking the pieces together,

as watchmen he stationed them. . . .

He bent Tiamat’s tail to form the Great Band as a bracelet.

Thus was “the Great Band,” the Asteroid Belt, created.

Figure 11

Having disposed of Tiamat and Kingu, Nibiru/Marduk once

again “crossed the heavens and surveyed the regions.” This time his

attention was focused on the “Dwelling of Ea” (Neptune), giving that

planet and its twinlike Uranus their final makeup. Nibiru/Marduk

also, according to the ancient text, provided Gaga/Pluto with its

final “destiny,” assigning to it “a hidden place”—a hitherto unknown

part of the heavens.

It was farther out than Neptune’s location; it

was, we are told, “in the Deep”—far out in space. In line with its

new position as the outermost planet, it was granted a new name: US.MI—“He Who Shows the Way,” the first planet encountered coming into the

Solar System—that is, from outer space toward the Sun.

Thus was Pluto created and put into the orbit it now holds.

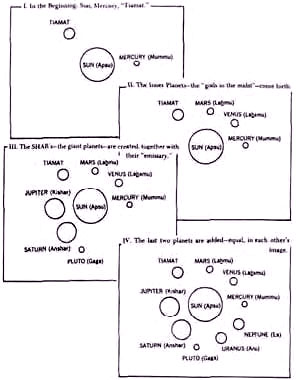

Figure 12

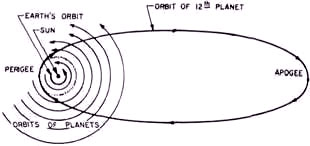

Having thus “constructed the stations” for the planets, NiIbiru/Marduk made two “abodes” for itself. One was in the

“Firmament,” as the asteroid belt was also called in the ancient

texts; the other far out “in the Deep” was called the “Great/Distant

Abode,” alias E.SHARRA (“Abode/Home of the Ruler/Prince”). Modern

astronomers call these two planetary positions the perigee (the

orbital point nearest the Sun) and the apogee (the farthest one)

(Fig. 12). It is an orbit, as concluded from the evidence amassed in

The 12th Planet, that takes 3,600 Earth-years to complete.

Thus did the Invader that came from outer space become the twelfth

member of the Solar System, a system made up of the Sun in the

center, with its longtime companion Mercury; the three olden pairs

(Venus and Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus and Neptune); the Earth

and the Moon, the remains of the great Tiamat, though in a new

position; the newly independent Pluto; and the planet that put it

all into final shape, Nibiru/Marduk (Fig. 13).

Figure 13

Modern astronomy and recent discoveries uphold and corroborate this

millennia-old tale.

WHEN EARTH HAD NOT BEEN FORMED

In 1766 J. D. Titius proposed and in 1772 Johann Elert Bode

popularized what became known as “Bode’s law,” which showed that

planetary distances follow, more or less, the progression 0, 2, 4,

8, 16, etc., if the formula is manipulated by multiplying by 3,

adding 4, and dividing by 10. Using as a measure the astronomical

unit (AU), which is the distance of Earth from the Sun, the formula

indicates that there should be a planet between Mars and Jupiter

(the asteroids are found there) and a planet beyond Saturn (Uranus

was discovered).

The formula shows tolerable deviations up until one

reaches Uranus but gets out of whack from Neptune on.

Bode’s law, which was arrived at empirically, thus uses Earth as its

arithmetic starting point. But according to the Sumerian cosmogony,

at the beginning there was Tiamat between Mars and Jupiter, whereas

Earth had not yet formed.

Dr. Amnon Sitchin has pointed out that if

Bode’s law is stripped of its arithmetical devices and only the

geometric progression is retained, the formula works just as well if

Earth is omitted—thus confirming Sumerian cosmogony:

|

Planet |

Distance from Sun (miles) |

Ratio of Increase

|

|

Mercury

Venus

Mars

Asteroids (Ti.Amat)

Jupiter

Saturn

Uranus |

36,250,000

67,200,000

141,700,000

260,400,000

484,000,000

887,100,000

1.783,900,000 |

—

1.85

2.10

1.84

1.86

1.83

2.01 |

Back to Contents

|