|

by Dan Brown

from

DanBrown Website

Digital

Fortress,

Phillips Exeter Academy, and the true story behind Dan

Brown’s bestseller...

In the Spring of 1995, on the campus of

Phillips Exeter Academy, the U.S. Secret Service made a bust...

-

THE TARGET : A teenage student

flagged by a government computer as being a threat to national

security.

-

THE CRIME : Sending E-mail to a

friend in which he said he thought President Clinton should be

shot.

-

THE MISTAKE : The same mistake many

Americans make every day...believing that what they say in

E-mail is private.

In the wake of the incident, Dan Brown,

an English teacher at the school, surprised by the government’s

apparent ability to "listen in", began researching the intelligence

community’s access to civilian communication. What he stumbled

across stunned him... an ultra-secret, $12 billion a year

intelligence agency that only 3% of Americans know exists.

This clandestine organization, known as the NSA (jokingly referred

to as No Such Agency), employs over 20,000 code-breakers, analysts,

technicians, and spies and has a 86-acre compound hidden in

Maryland. Founded over half a century ago by President Truman, the

NSA’s technology is unrivaled. They have the ability to monitor all

of our digital communications--cellular phone, FAX, and E-mail. They

are bound by presidential directive to do whatever it takes to

protect our national security... including "snoop" our most private

conversations if necessary.

Brown coaxed two ex-NSA cryptographers to speak to him via anonymous remailers (an E-mail protocol that ensures both parties privacy),

and the cryptographers, each unaware of the other, told identical

stories... incredible accounts of NSA submarines that listened in on

underwater phone cables, of a terrorist attack on the New York Stock

Exchange that never went public, and also of a chilling new NSA

technology--a multi-billion dollar supercomputer capable of

deciphering even the most secure communications. Nonetheless, the

cryptographers sang the praises of the NSA and insisted that

ensuring our nation’s security can only be done at the expense of

civilian privacy.

"The battle between privacy and security," says

Brown, "has no

clear-cut answers. The stakes are enormous. All I know is that when

I learned the truth about the NSA, I had to write about it."

If he disappears... we’ll know who to blame.

Did You

Know?

Some surprising facts about your lack of privacy.

-

In large cities, Americans are

photographed on the average of 20 times a day.

-

Everything you charge is in a

database that police, among others, can look at.

-

Supermarkets track what you

purchase and sell the information to direct-mail marketing

firms.

-

Your employer is allowed to read

your E-Mail, and if you use your company’s health insurance

to purchase drugs, your employer has access to that

information.

-

Government computers scan your

E-Mail for subversive language.

-

Your cell phone calls can be

intercepted, and your access numbers can be cribbed by

eavesdroppers with police scanners.

-

You register your whereabouts

every time you use an ATM, credit card, or use EZ PASS at a

toll booth.

-

You are often being watched when

you visit web sites. Servers know what you’re looking at,

what you download, and how long you stay on a page.

-

A political candidate found his

career destroyed by a newspaper that published a list of all

the videos he had ever rented.

-

Most "baby monitors" can be

intercepted 100 feet outside the home.

-

Intelligence agencies now have

"micro-bots" -- tiny, remote control, electronic "bugs" that

literally can fly into your home and look around without

your noticing.

-

Anyone with $100 can tap your

phone.

-

A new technology called TEMPEST

can intercept what you are typing on your keypad (from 100

feet away through a cement wall.)

-

The National Security Agency has

a submarine that can intercept and decipher digital

communications from the RF emissions of underwater phone

cables.

Author FAQ

-

NSA secrets, anecdotes, privacy info, and a

surprising look into the future

DIGITAL FORTRESS, the controversial thriller about the ultra-secret

U.S. National Security Agency, spent 15 weeks as the #1 national

bestselling E-book and was inspired by a true event.

AUTHOR INTERVIEW

"I couldn’t figure out how the

Secret Service knew what these kids were saying in their

E-mail."

Q: A rather startling event inspired you to write

Digital

Fortress. Can you elaborate on what happened?

A: A few years ago, I was teaching on the campus of Phillips

Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. One Spring day, unannounced,

the U.S. Secret Service showed up and detained one of our

students claiming he was a threat to national security. As it

turned out, the kid had sent private E-mail to a friend saying

how much he hated President Clinton and how he thought the

president should be shot. The Secret Service came to campus to

make sure the kid wasn’t serious. After some interrogation the

agents decided the student was harmless, and not much came of

it. Nonetheless, the incident really stuck with me. I couldn’t

figure out how the secret service knew what these kids were

saying in their E-mail.

I began doing some research into where organizations like the

Secret Service get their intelligence data, and what I found out

absolutely floored me. I discovered there is an intelligence

agency as large as the CIA... that only about 3% of Americans

knows exists.

It is called the National Security Agency (NSA), and it is home

to the country’s eavesdroppers. The agency functions like an

enormous vacuum cleaner sucking in intelligence data from around

the globe and processing it for subversive material. The NSA’s

super-computers scan E-mail and other digital communiqués

looking for dangerous word combinations like "kill" and

"Clinton" in the same sentence.

The more I learned about this ultra-secret agency and the

fascinating moral issues surrounding national security and

civilian privacy, the more I realized it was a great backdrop

for a novel. That’s when I started writing Digital Fortress.

"The NSA is in charge of waging the information war-- stealing

other people’s secrets while protecting our own."

Q: The NSA sounds fascinating, can you tell me more about it?

A: The NSA was founded at 12:01 on the morning of November 4th,

1952 by President Truman. No note of this event was made in the

Congressional Record. The NSA’s charge was simple--to intercept

and decipher intelligence information from hostile governments

around the globe. Secondly, it was to create the means to enable

secure communications among U.S. military and officials.

Put another way, the NSA is in charge of waging the information

war--stealing other people’s secrets while protecting our own;

they are not only the nation’s code-breakers, but also our

code-writers. Today the agency has a $12 billion annual budget,

about 25,000 employees, and an 86-acre heavily armed compound in

Fort Meade, Maryland. It is home to the world’s most potent

computers as well as some of the most brilliant cryptographers,

mathematicians, technicians, and analysts. Digital Fortress is

about a brilliant female cryptographer who works inside these

sacred walls.

"Intelligence analysts joke that the acronym ’NSA’ really stands

for ’No Such Agency.’"

Q: Why have so few people heard of the NSA?

A: In the novel the intelligence analysts joke that the acronym

"NSA" really stands for "No Such Agency" or "Never Say

Anything." Seriously though, the NSA is clandestine because it

has to be. It is responsible for protecting this nation from

some very powerful and hostile forces; often times this involves

practices that civilians might find intrusive or immoral.

The NSA is far more effective if it is immune to the public

scrutiny that most of the other agencies have to endure.

Although not many people have heard of the NSA, that fact is

quickly changing. Certainly those people familiar with the

intelligence community are aware of the NSA’s existence and

general code of conduct. Computer users who are savvy about

issues of privacy in the digital age are also more and more

aware of the NSA’s existence and practices.

The battle for privacy rights in a digital world is starting to

take center stage, and I suspect it will be THE major issue of

the next decade. We can all expect to hear a lot more about the

NSA as the battle surrounding national security and civilian

privacy develops.

"We communicated via anonymous remailers such that our

identities remained secret."

Q: How did you get so much information on such a clandestine

agency?

A: Much of the data on the NSA is public domain if you know

where to dig. James Bamford wrote a superb exposé of the agency,

and there are a number of former intelligence sources who have

written extensive white-papers on the subject. I was also

fortunate to befriend two former NSA cryptographers while

researching the book. We communicated via anonymous remailers

such that our identities remained secret.

At first, I was surprised with the information they were

sharing, and I suspected, despite their obvious knowledge, that

they were probably not who they said they were. But the more we

spoke, the more I was convinced they were authentic. Neither one

knew about the other, and yet they told almost identical

stories. When I asked why they were sharing intelligence data

with me, the response startled me. One cryptographer put it this

way,

"I am a mathematician, not a politician. The

NSA’s

technologies and practices are necessary, believe me, but their

level of secrecy is dangerous. It breeds distrust. I believe it

is good for everyone that the agency is gradually coming to the

public eye. I am not sharing classified information; the

information I am sharing is already out there, but it is

skillfully buried. I’m only bringing it to the surface."

"There used to be barriers around information. Technology has

changed that."

Q: Ten years ago we never read about privacy rights, now it is

an enormous issue. Why?

A: Barriers. There used to be barriers around information.

Technology has changed that. It used to be we sent our messages

in sealed envelopes with the U.S. postal service; now we E-mail.

Global corporations used to gather for closed-door meetings; now

they teleconference. Once we sent important documents with

bonded couriers; now we FAX. All of these transfers take place

through a vast network of cables and satellites that is

impossible to keep entirely secure. Technology has made global

communication more efficient, but the down side is that there is

a lot more of each of us floating around out there waiting to be

intercepted.

"ITT and Western Union were under enormous political pressure to

cooperate silently... and they did so."

Q: Does the government really read our E-mail?

A: Government monitoring of civilian communication is something

that has been going on for decades. Even though the public is

widely unaware, government officials and specialists in

privacy-related fields are certainly aware of the practice. The

debate over its ethics is complex because a precedent exists

that intercepting certain E-mail, cellular phone, and FAX

communications can help law-enforcement officials catch

dangerous criminals. The question turns into one of civilian

privacy vs. national security. In the 1950’s the NSA’s then

top-secret Project Shamrock intercepted and scanned all

telegrams sent in or out of the country; ITT and Western Union

were under enormous political pressure to cooperate

silently... and they did so.

Project Shamrock stayed in effect until 1975. Nixon’s

Huston

Plan and later Project Minaret further relaxed regulations on

monitoring civilian communications and even activated enormous

watch-lists of U.S. civilians whose communiqués were regularly

tapped. Just recently, of course, the FBI caught the infamous

hacker Jose Ardita by secretly monitoring computer activity at

Harvard University. As you can see, this sort of activity is

nothing new.

"The loopholes are obvious..."

Q: But aren’t there laws against intercepting E-mail?

A: Current laws are shaky at best. The Electronic Communications

Privacy Act (ECPA) provides that personal E-mail cannot be

intercepted while it is in transit. However, once the E-mail is

digitally "stored" it is fair game and officials can legally

gain access. The irony in the law is that E-mail travels by

copying itself from server to server; the moment it is "in

transit" it is also stored on servers across the country.

The loopholes are obvious. It’s hard to prove that unwarranted

monitoring takes place, but most privacy specialists agree that

monitoring is rampant, a point well-taken when you consider the

following: Government Incentive -- Terrorist activity against

the U.S. is on the rise (some from domestic sources), and the

incentive certainly exists to protect national security in

anyway possible. It’s Easy - The technology now exists for the

government to secretly scan enormous quantities of data very

cost effectively. It’s Legal - The current laws are written such

that they do not hinder the intelligence agencies in any real

way from scanning civilian communications for subversive

activity. Historical Precedent - The intelligence community has

a long history of protecting national security through domestic

intelligence gathering.

Operation Shamrock and Minaret are two examples. Daily Proof -

Almost every day there are stories in the news of civilians

arrested for child pornography, embezzlement, drug trade, etc.

These arrests usually hold up in court based on evidence from

intercepted private communications. Officials often have

court-orders when they tap E-mail and phones, but it is not

difficult to imagine time-sensitive crises where court-orders

are not feasible and laws are bent in the name of protecting the

common good.

"If I send E-mail that reads, ’Tonight I’m taking out my wife,’

how would you interpret that?"

Q: Most individuals are law-abiding citizens, why should they

care if a government agency might be listening in to their

personal communications?

A: First, there is the obvious moral issue of whether or not we

want to live in an Orwellian society where big brother is

peering in from all sides. But more immediate concerns are those

of abuse and misinterpretation of data. For example, if I send

E-mail that reads, "Tonight I’m taking out my wife," how would

you interpret that? Am I treating my wife to a date, or am I

killing her? Because language is sometimes ambiguous, it runs

the risk of misunderstanding. The results can be disastrous.

"The priest made a single typo that changed his life forever."

Q: Can you give us any "real life" horror stories of instances

of abuse or misinterpretation?

A: Absolutely. There is one I heard recently that has become

somewhat of an urban legend. Although I can’t vouch for the

accuracy of the story, it’s a perfect example of the sorts of

things that we now hear happening all the time. Apparently, last

year a priest from Utah sent E-mail to his sister in Boston. In

his message he mentioned that some local teenagers had stopped

by his church that day and baked him brownies. Hoping to impress

his sister with his technological wizardry, he borrowed the

church’s new digital camera and took a photo of the brownies.

Then he attached the photo to his E-mail and sent it off. Of

course everything should have been fine.

Alas, it was not. In a cruel twist of fate, while typing his

E-mail the priest made a single typo that changed his life

forever. While writing the phrase "teenagers baked brownies",

instead of typing "B" for baked, he missed and hit the letter

"N" (the letter directly next to the "B"), resulting in the

phrase "teenagers naked brownies."

Because he had unknowingly typed the words "naked" and

"teenagers" next to each other in his E-mail, his message was

flagged by a secret government computer scanning for child

pornographers on the Internet. To make matters worse (much

worse) the priest had attached a photo to his E-mail, so his

transmission was flagged top-priority for immediate analysis.

When the task force went to examine the photo, however, they

found that the file was corrupt and could not be opened. All

they knew was that the photo was entitled "Brownies", and it was

sent by a priest who was writing about naked teenagers. They

tracked the priest’s identity through his Internet service

provider and secretly began investigating his church. They found

to their horror that both the Cub Scouts and the Brownies met at

there on a regular basis. They concluded that this priest had

been sending pictures of naked Brownies... a felony. They

arrested him.

"The government is far less intrusive than most forces."

Q: Is the government the only force that pries into our lives?

A: Absolutely not. In fact, the government is far less intrusive

than most forces. With the evolution of the personal computer,

small companies and even individuals can now keep track of

enormous databanks. Can you imagine ten years ago your

neighborhood grocer making a note of every single item you as a

customer purchased? Now it happens automatically at the

check-out scanners. If you buy groceries with a credit or debit

card, a detailed record of your personal purchasing preferences

is instantly cataloged. Marketing agencies pay top dollar for

these lists.

"Even our simplest daily actions are recorded and can come back

to haunt us."

Q: Can you give us other examples of how we are spied on?

A: The list is endless. Aside from the cameras that are trained

on us at all ATM’s, toll-booths, and large department stores,

there is plenty of subtle spying. Sweepstakes are a good

example. If you enter $100,000 dollar sweepstakes, you should be

aware that the company sponsoring the sweepstakes will make ten

times that much selling your personal information to direct-mail

marketing firms. Another example is the ubiquitous "free blood

pressure clinic." Many of these clinics are set up NOT to check

your blood pressure but rather to gather prospecting lists for

pharmaceutical companies.

The world-wide-web is anything but private. Many computer users

still don’t realize that the web sites they visit will, in many

cases, track their progress through the site--how long a user

stays, what he lingers over, what files he downloads. If you’re

visiting sites on the web that you don’t want anyone to know

you’re visiting, you better think again.

Even our simplest daily actions are recorded and can come back

to haunt us. One of my favorite stories is of a political race

in California in which a candidate was running on a platform of

conservative family values. His challenger simply went to the

man’s local Blockbuster Video and tipped the clerk $100 to print

out a list of every movie the candidate’s family had ever

rented. The list contained some titles that were by no means

Disneyesque. He leaked the list to the papers, and the election

was over before it began.

"Ultimately, the price we pay for national security will be an

almost total loss of privacy."

Q: What’s in store for us in the future, more or less privacy?

A: Less. Every day, civilians have fewer and fewer secrets, and

it’s only going to get worse. The world has become a dangerous

place, and our security is harder to protect. Criminals have

access to the same technology we do. If we want the government

to catch terrorists who use E-mail or cellular phones, we have

to provide a means for them to monitor these types of

communication.

There are plenty of very sharp folks who are working hard to

find some happy medium-- key escrow systems that would enable

officials to monitor communications only with a court order--but

despite all the efforts to leave the public some semblance of

secrecy, ultimately the price we pay for national security will

be an almost total loss of privacy.

"Currently, criminals can obtain the necessary level of

anonymity to commit their crimes. That is changing."

Q: Is this death of privacy all bad news?

A: Not entirely. Many people will want my head for saying that,

but if you think about it, most of the bad things that occur in

society happen because people have privacy -- that is to say,

criminals can obtain the necessary level of anonymity to commit

their crimes.

One needs privacy to break the law and get away with it. Child

molesters, terrorists, organized criminals--- they all work in

private. If their communications and daily activities are less

clandestine, they will not last long. Of course, there is the

obvious question of whether or not we trust the law-enforcement

officials who are listening in.

Whether or not we trust those people we’ve elected to watch over

us is a question asked by the antagonist in

Digital Fortress--"Quis

custodiet ipsos custodes," he quotes -- "Who will guard the

guards?"

"Ultimately, privacy will not survive the digital revolution."

Q: Isn’t there any way to protect ourselves from prying eyes?

A: Ultimately, privacy will not survive the digital revolution.

We live in a society experiencing exponential technological

growth. Within the decade, most of our daily activities will be

conducted through our home computers-- paying taxes, voting,

shopping, all of our entertainment, movie-downloads will replace

videos, music downloads will replace CD’s... all of this

personal information will be zipping around between satellites

and through cables...it would be naive to believe that we will

develop some foolproof method of keeping all this information

secure.

"The important thing for us to do is to ensure that the death of

privacy is bilateral."

Q: How should we prepare ourselves for the end of privacy?

A: The important thing for us to do is to ensure that the death

of privacy is bilateral--that is, that while snoopers know more

about us, we know more about them. If a supermarket or clinic is

selling our personal information, we should know to whom. If a

web site plans to watch our every move, we should be warned

before we enter the site.

"The death of privacy may have some wonderful side effects we

don’t yet imagine--it may just make us a more moral society..."

Q: The scenario sounds grim. Can you leave us with any words of

hope?

A: Sure. The death of privacy may have some wonderful side

effects we don’t yet imagine--it may just make us a more moral

society. If we are more visible to our peers, our behavior as a

society will undoubtedly improve. Think about it... if your

whole town knows when you are on the Internet sneaking a peek at

Lois Lane in her underwear, you might just decide to do

something else... maybe even curl up with a good book.

The NSA

- Links to the NSA’s official site as well

as other intelligence resources (courtesy of FAS)

N.287 dated 9 May 1996 N.287 dated 9 May 1996

page 2

The Best U.S. Intelligence Web Site

The best Internet site on the American intelligence community is

undoubtedly one run by the

Federation of American Scientists (FAS)

which has been fighting a long battle to declassify secrets that

no longer need to be kept in the Cold War’s aftermath (Project

on Government Secrecy-PGS) and to encourage an overhaul of

intelligence services (Intelligence Reform Project-IRP).

The site offers a lot of striking documents

and pictures. In their pages, Steven Aftergood and John Pike,

leading figures in PGS and IRP, show satellite images (with

resolutions from 10 to 1 meter) of the main buildings housing

American intelligence agencies as well as pictures of the same

premises and maps indicating their exact location.

When the Brown commission published its report on reforms in

American intelligence on March 1 it recommended that the

community’s budget not be disclosed. By cross-checking several

documents and using reverse engineering methods, FAS published a

relatively precise estimate of what is effectively the

community’s budget of around $28 billion (a detailed analysis

with maps and tables is available on

http://www.fas.org/irp/commission/budget.htm).

President Bill Clinton indirectly paid tribute to that effort on

April 23 by suggesting that Congress adopt a bill to make the

budget public.

Drawing on open sources, Pike also drew up a first directory of

160 companies that work for American intelligence (http://www.fas.org/irp/contract.html).

The directory is constantly updated on the web. Recently, FAS

persuaded John Deutch to make the Director of Central

Intelligence’s report for 1994 public and published it in March

on its site (http://www.fas.org/irp/cia94.htm)

In addition, Aftergood publishes a newsletter entitled

Secrecy &

Government Bulletin (SG&B) every month. Now in its fifth year,

the publication has produced a number of major scoops ever since

it revealed the existence of an on-going Special Access Program

for the first time in 1991. Named Timber Wind, the project to

build a nuclear-powered engine for a rocket was finally

scrapped. SG&B is currently financed by the

Rockefeller Family

Fund, the CS Fund and several other donors. But it is seeking

fresh funding in order to continue its work.

Someone

Is Listening -

An overview of the battle...

Excerpt from the L.A. TIMES

"DEMANDING THE ABILITY TO SNOOP"

By Robert Lee Hotz

TIMES SCIENCE WRITER

Someone Is Listening...

When Charles and Diana discovered millions of people were

reveling in their most intimate telephone calls, the world’s

most public couple had to face the facts of private life in the

electronic age.

In a world of cellular phones, computer networks, electronic

mail and interactive TV, the walls might as well have ears.

With the explosion of such devices, more people and companies --

from banks to department stores -- seem to have more access to

more information that someone wants to keep private. In

response, computer users are devising their own electronic codes

to protect such secrets as corporate records, personal mail or

automated teller transactions.

Historically, the biggest ears have belonged to the federal

government, which has used surveillance techniques designed to

track down criminals and security risks to keep electronic tabs

on subjects ranging from civil rights leaders to citizens making

overseas calls.

But, today, federal officials are afraid that advanced

technology, which for almost 50 years has allowed them to

conduct surveillance on a global scale, is about to make such

monitoring impossible.

Now, federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies are

insisting on their right to eavesdrop.

The government is proposing a standardized coding, or

encryption, system that would eliminate eavesdropping by anyone

except the one holder of the code’s key -- the government

itself.

To ensure that federal agents and police can continue to wiretap

communications, the National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST) is introducing a national electronic code. It

will cover all telephone systems and computer transmissions,

with a built-in back door that police can unlock with a court

order and an electronic key.

White House and FBI officials insist they have no way to force

any company to adopt the new technology. They will not outlaw

other forms of coding, they said.

But experts say a series of regulatory actions involving

Congress, the State Department, the U.S. attorney general,

export licensing restrictions and the purchasing power of the

federal government will effectively force people to use the

code.

The government’s plan has triggered an outcry among computer

users, civil rights groups and others. The American Civil

Liberties Union and groups of computer professionals say the

plan raises major constitutional questions. Federal laws are

designed to limit the government’s ability to wiretap, not

guarantee it, they say.

"Where does the U.S. government get the right to understand

everything that is transmitted?" asked Michel Kabay, director of

education for the National Computer Security Assn. in Carlisle,

Pa.

Not so many years ago, powerful encryption techniques were the

monopoly of military and intelligence agencies. Over time,

computer experts and corporate cryptographers created codes to

protect their private communications. Some of these scramble

electronic signals so thoroughly that even the supercomputers of

the National Security Agency cannot decipher them. One of the

best codes, called

Pretty Good Privacy, is free and can be

downloaded from computer network libraries around the world --

yet it still contains safeguards that protect its secrets from

prying eyes.

Combined with advances in fiber optics and digital

communications, these codes enable people to send electronic

mail, computer files and faxes the government cannot read, and

to make phone calls even the most sophisticated wiretapper

cannot understand.

As new technologies converge to form the roadbed of a national

information superhighway, the government faces the prospect of

millions of people around the world communicating in the

absolute privacy of the most secure codes science can devise.

At the same time, hundreds of phone companies channel calls

through new digital switches into long-distance fiber-optic

cables where, translated into light-speed laser pulses, they may

elude interception more easily. Dozens of other companies are

organizing global wireless digital networks to send phone calls,

faxes and computer files over the airwaves to people no matter

where they are or how often they move.

Given all this, NIST officials say the new code, called

Skipjack, is the government’s attempt to strike a balance

between personal privacy and public safety.

They say it will protect people from illicit eavesdropping,

while allowing an authorized government agent to unlock any

scrambled call or encrypted computer message. It could be

incorporated into virtually every computer modem, cellular phone

and telecommunications system manufactured in the United States.

Designed by the National Security Agency, which conducts most of

the country’s communications surveillance, the code is one facet

of an ambitious government blueprint for the new information

age.

But critics say the code is just one of several steps by federal

law enforcement groups and intelligence agencies to vastly

expand their ability to monitor all telecommunications and to

access computer databases.

Federal officials acknowledge that they are even considering the

idea that foreign governments should be given the keys to unlock

long-distance calls, faxes and computer transmissions from the

United States. An international agency, supervised by

the United

Nations or Interpol, might be asked to hold in trust the keys to

electronic codes, said Clint Brooks, a senior NSA technical

adviser.

The Skipjack furor pits the White House, the FBI and some of the

government’s most secret agencies against privacy advocates,

cipher experts, business executives and ragtag computer-zoids

who say codes the government cannot break are the only way to

protect the public from the expanding reach of electronic

surveillance.

On the computer networks that link millions of users and

self-styled

Cypherpunks

-- a group of encryption specialists --

the federal proposal has stirred fears of an electronic Big

Brother and the potential abuse of power.

"It really is Orwellian when a scheme for surveillance is

described as a proposal for privacy," said Marc Rotenberg,

Washington director of Computer Professionals for Social

Responsibility.

Encryption is the art of concealing information in the open by

hiding it in a code. It is older than the alphabet, which is

itself a code that almost everyone knows how to read.

Today, electronic codes conceal trade secrets, protect sensitive

business calls and shelter personal computer mail. They also

scramble pay-per-view cable television programs and protect

electronic credit card transactions.

Everyone who uses an automated teller machine is entrusting

financial secrets to an electronic code that scrambles

transmissions between the automated teller and the bank’s main

computer miles away. One inter-bank network moves $1 trillion

and 1 million messages around the world every day, swaddled in

the protective cocoon of its code.

Nowhere has the demand for privacy grown so urgent as on the

international confederation of computer systems known as the

Internet. There, in a proving ground for the etiquette of

electronic communication, millions of people in dozens of

countries are adopting codes to protect their official business,

swap gossip and exchange personal notes elbow-to-elbow in the

same crowded electronic bazaar.

"People have been defending their own privacy for centuries with

whispers, darkness, envelopes, closed doors, secret handshakes

and couriers," said Eric Hughes, moderator of the

Cypherpunks,

an Internet group that specializes in encryption.

"We are

defending privacy with cryptography, with anonymous

mail-forwarding systems, with digital signatures and with

electronic money."

And it’s working. The technology is leaving law enforcement

behind.

Federal officials who defend the Skipjack plan say they are

worried about too much privacy in the wrong hands.

"Are we going to let technology repeal this country’s wiretap

laws?" asked James K. Kallstrom, FBI chief of investigative

technology. Under U.S. law, any wiretap not sanctioned by a

court order is a felony.

Federal law enforcement agencies and intelligence groups were

galvanized last fall when AT&T introduced the first inexpensive

mass-market device to scramble phone calls. The scrambler

contains a computer chip that generates an electronic code

unique to each conversation.

FBI officials paled at what they said was the prospect of

racketeers, drug dealers or terrorists being able to find

sophisticated phone scramblers to code and decode calls at the

nearest phone store.

National security analysts and Defense Department officials say

U.S. intelligence agencies find the new generation of computer

encryption techniques especially unsettling. It promises to make

obsolete a multibillion-dollar investment in secret surveillance

facilities and spy satellites.

"We would have the same concerns internationally that law

enforcement would have domestically about uncontrolled

encryption," said Stewart A. Baker, NSA general counsel.

NSA officials are reluctant to discuss their surveillance

operations, but they said they would not want terrorists or

anyone else "targeting the United States" to be able to

communicate in the secrecy provided by unbreakable modern codes.

The Clinton Administration is expected to advise

telecommunications and computer companies this fall to adopt the

Skipjack code as a new national encryption standard used by the

government, the world’s largest computer user, and anyone who

does business with it.

The government also will be spending billions in the next 10

years to promote a public network of telecommunications systems

and computer networks called the National Information

Infrastructure. Any firm that wants to join will have to adopt

the Skipjack code.

Skipjack is being offered to the public embedded in a

tamper-proof, $26 computer circuit called the Clipper Chip. It

is produced by Mykotronx Inc., a computer company in Torrance.

To make it easier for agents to single out the proper

conversation in a stream of signals, every Clipper Chip has its

own electronic identity and broadcasts it in every message it

scrambles.

Federal agents conducting a court-authorized wiretap can

identify the code electronically and then formally request the

special keys that allow an outsider to decipher what the chip

has scrambled.

Federal officials say they expect companies to incorporate the

chip into consumer phone scramblers, cellular phones and

"secure" computer modems. Within a few years, FBI officials say,

they expect the Skipjack code to be part of almost every

encryption device available to the average consumer.

Many companies say they are leery of adopting the sophisticated

electronic code, even though it could protect them from foreign

intelligence agencies and competitors seeking their trade

secrets. But AT&T, which has a long history of cooperating with

the government on communications surveillance, has already

agreed to recall the company’s consumer scramblers and refit

them this fall with the new chip.

Even without Skipjack and the Clipper Chip, advanced computers

and electronic databases already have expanded government’s

ability to track and monitor citizens.

Searches of phone records, computer credit files and other

databases are at an all-time high, and court-authorized wiretaps

-- which listened in on 1.7 million phone conversations last

year -- monitor twice as many conversations as a decade ago,

federal records show.

The General Accounting Office says that federal agencies

maintain more than 900 databanks containing billions of personal

records about U.S. citizens.

This type of easy access to electronic information is addictive,

critics contend.

Since the FBI set up its computerized National Criminal

Information Center in 1967, for example, information requests

have grown from 2 million a year to about 438 million last year,

and the criminal justice database itself now encompasses 24

million files.

The FBI records system, like computer files at the Internal

Revenue Service, is "routinely" used for unauthorized purposes

by some federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, the

General Accounting Office (GAO) said.

GAO auditors found that some police agencies have used the

FBI

system to investigate political opponents. Others have sold FBI

information to companies and private investigators. In Arizona,

a former law enforcement official used it to track down his

estranged girlfriend and kill her, the auditors reported.

What the government can’t find in its own files, it can obtain

from any one of hundreds of marketing firms that specialize in

compiling electronic dossiers on citizens. The FBI is seeking

authority from Congress to obtain those records without

consulting a judge or notifying the individual involved, which

is required now.

Information America, for example, offers data on the location

and profiles of more than 111 million Americans, 80 million

households and 61 million telephone numbers. Another firm

specializes in gay men and lesbians.

A third, a service for doctors called Patient Select, singles

out millions of people with nervous stomachs.

Computer experts say encryption can draw a curtain across such

electronic windows into private life.

In fact, the FBI is planning to encrypt its criminal justice

computer files.

"Recent years have seen technological developments that diminish

the privacy available to the individual," said Whitfield Diffie,

a pioneering computer scientist who helped invent modern

cryptography.

"Cameras watch us in the stores, X-ray machines

search us at the airport, magnetometers look to see that we are

not stealing from the merchants, and databases record our

actions and transactions.

"Cryptography," he said, "is perhaps alone in its promise to

give us more privacy rather than less."

NEXT:

Inside the company that makes the secret chip.

Scrambling for Privacy

As more people and companies adopt codes to protect their

telephone calls, faxes and computer files, the federal

government has proposed a national encryption standard that will

allow people to protect their privacy while ensuring that law

enforcement agents can still wiretap telecommunications. Here is

how it would work:

-

When someone using a Skipjack-equipped secure phone calls

another secure phone, chips inside the phone generate a unique

electronic code to scramble the conservation.

-

The chip also broadcasts a unique identifying serial number.

-

If a law enforcement agent wants to listen in, he first must

obtain a court order and the get the chip’s serial number from

the signal.

-

The agent obtains takes that number to the Treasury Department

and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which

keep the government’s digital keys to the chip.

-

The keys are combined to unscramble the conversation. When legal

authorization for the wiretap expires, the keys are destroyed.

-

Two 80-digit random strings of zeros and ones are selected.

-

They are factored together to form the chip’s unique key the key

is then split in half.

-

Each half is paired with the serial number of the chip to form

two keys.

-

One is kept by the Treasury Department and the other by the

National Institute of Standards and Technology.

-

Sources: U.S. National Security Agency, Mykotronx Inc.

Someone Is Listening

To eavesdrop on a telephone conversation, law enforcement agents

must obtain a court order, but they can use other devices, such

as so-called pen registers, that record incoming or outgoing

telephone numbers without actually listening to the calls.

WIRETAP COURT ORDERS

From 1985 through 1991, court-ordered wiretaps resulted in 7,324

convictions and nearly $300 million in fines. A single court

order can involve many telephones. This data includes federal

and state orders, but does not include many national security

wiretaps.

1985: 784

1986: 754

1987: 673

1988: 738

1989: 763

1990: 872

1991: 856

1992: 919 *

MONITORING PHONE ACTIVITY

Pen registers are devices that record only the outgoing numbers

dialed on a telephone under surveillance. Below are the number

of pen registers in use, by year.

1987: 1,682

1988: 1,978

1989:

2,384

1990: 2,353

1991: 2,445

1992: 3,145

Sources:

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, U.S. Justice

Department, House Judiciary Committee

Turning

Cell Phones Into Ankle Bracelets

Report on how cellular phones will soon be

used by government officials to track your whereabouts

’E911’ Turns Cell Phones into Tracking Devices

by Chris Oakes

3:10pm 6.Jan.98.PST

Cell phones will be taking on a new

role in 1998, beginning a slow transition to becoming user

tracking devices. The outcome of this shift reassures some, but

has others calling for restrictions on how cell-locating

information can be used.

The impending first phase of the FCC’s rules is aimed at

enabling emergency services personnel to quickly get information

on the location of a cell phone user in the event of a 911 call.

By April, all cellular and personal communications services

providers will have to transmit to 911 operators and other

"public safety answering points" the telephone number and cell

site location of any cell phone making a 911 call.

The aim of the law is to bring to cell phone users the same

automatic-locating capability that now exists with wireline

phones. But while the FCC’s aim is simple on the surface - to

make it easier for medical, fire, and police teams to locate and

respond to callers in distress - the technology is also giving

rise to concerns over the ease with which the digital age and

its wireless accouterments are bringing to tracking individuals.

"The technology is pretty much developing to create a more and

more precise location information. The key question for us is

’what is the legal standard for government access?’" says

James

Dempsey, senior staff counsel at the

Center for Democracy and

Technology (CDT)

Those seeking restrictions on the use of cell phone tracking

information emphasize that, unlike the stationary wireline

phones, a cell phone is more specifically associated with an

individual and their minute-by-minute location.

In December, the FCC began requiring wireless providers to

automatically patch through any emergency calls made through

their networks. Subscriber or not, bills paid or unpaid, anyone

with a cell phone and a mobile identification number was thus

guaranteed to see their 911 calls completed.

1998 brings new rules into place that take that initial action

much further. By April, emergency service personnel will receive

more than just the call - they’ll also get the originating cell

phone’s telephone number and, more significantly, the location

of the cell site that handled the call.

The FCC’s "Enhanced 911 services" requirements that wireless

providers make this information available is the beginning of a

tracking system that by 2001 will be able to locate a phone

within a 125-meter radius.

To provide this precise location information, Jeffrey Nelson of

the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association says

different carriers will choose different methods of gathering

location information, but all of them involve detecting the

radio frequencies sent from the phone to service antennas.

Because a phone sends additional signals to other antennas in

addition to the primary one, "triangulation" lets them calculate

the caller’s whereabouts within that multi-antenna region. All

this happens automatically when a cell phone is turned on.

The upshot, Nelson says, is that cellular callers will "be able

to make a call to 911 or the appropriate emergency number

without having to explain where they are." He cites a case in

which a woman stranded in a blizzard, unable to tell where she

was, was located by use of her cell phone. Various systems are

being tested by most providers, he reports, but many are already

working with methods to provide such location information today.

But this tracking issue has privacy advocates seeking preventive

legislation to see that the instant accessibility of the

information to emergency units doesn’t just as easily deliver

the same tracking information to law enforcement agencies - from

local police on up to the FBI.

"The FCC has been in the picture from the 911 perspective," says

Dempsey of the Center for Democracy and Technology.

But to him,

this obvious emergency benefit of E911 necessitates legal action

to draw boundaries around its use by other organizations, namely

law enforcement.

That’s where the issue runs into the same waters as the

controversy surrounding the expansion of the Communications

Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA). That 1994 law was meant to

keep communications companies from letting the advancement of

digital and wireless technology become an obstacle to the

surveillance needs of law enforcement agencies. But

the CDT and

the

Electronic Frontier Foundation, among others, have argued

that as CALEA undergoes actual implementation (a process that is

still ongoing), the FBI is seeking to expand its surveillance

capabilities by seeking unjust specifications for phone systems’

compliance with the law.

Dempsey wants to see both CALEA and the new E911 requirements be

implemented with clear restrictions on the ability of law

enforcement to tap into personal information on users,

especially their whereabouts at any one time.

With the implementation of E911, Dempsey says that in effect,

"your phone has become an ankle

bracelet. Therefore we are urging the standard for

government access be increased to a full probable cause

standard. [Law enforcement agencies] have to have suspicion

to believe that the person they are targeting is engaged in

criminal activity."

Currently, he says, to get a court

order allowing the surveillance of cell phone use, law

enforcement only has to prove that the information sought - not

the individual - is relevant to an ongoing investigation.

"It says to law enforcement

you’ve got to have a link between the person you’re

targeting and the crime at issue," Dempsey says. "It cannot

be a mere fishing expedition."

While the CDT and others seek

beefed-up constitutional restrictions on the ability for law

enforcement to obtain court orders in such cases, the FBI says

the process for obtaining such court orders is already adequate.

"We work under the strict

provisions of the law with regard to our ability to obtain a

court order," said Barry Smith, supervisory special agent in

the FBI’s office of public affairs.

"Law enforcement’s access to

[cell phone data] falls very much within the parameters of

the Fourth Amendment."

He also says that under CALEA, the

call data the FBI seeks does not provide the specific location

of a wireless phone.

The FCC and its E911 requirements are distinct from CALEA, but

because they offer the ultimate form of tracking information -

far more instantly and explicitly than the FBI is seeking in the

implementation of CALEA, E911 may be ripe for access by law

enforcement for non-emergency needs.

As for the distinction between the dispute over CALEA and the

FCC’s E911 services, Smith says the latter has nothing to do

with the FBI. "There’s not any crossover between the two."

But, says Dempsey, when law enforcement serves a court order,

they could get location information through the requirements

established by E911.

Spying in Europe

The Echelon System

ECHELON article From Eurobytes

From London Daily Telegraph

ONLINE SURVEILLANCE

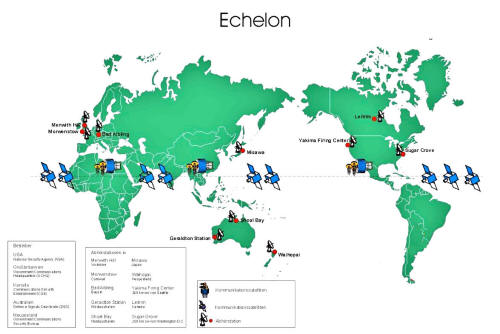

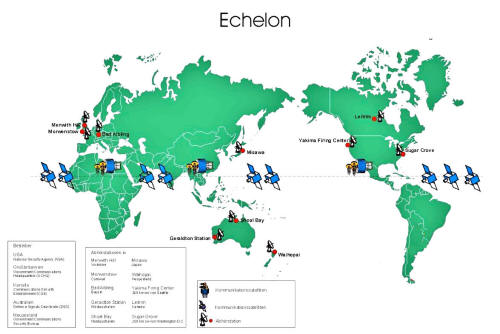

Rumors have abounded for several years of a massive system

designed to intercept virtually all email and fax traffic in the

world and subject it to automated analysis, despite laws in many

nations (including this one) barring such activity. The laws

were circumvented by a mutual pact among five nations. It’s

illegal for the United States to spy on it’s citizens. Likewise

the same for Great Britain. But under the terms of the UKUSA

agreement, Britain spies on Americans and America spies on

British citizens and the two groups trade data. Technically, it

may be legal, but the intent to evade the spirit of the laws

protecting the citizens of those two nations is clear.

The system is called ECHELON, and had been rumored to be in

development since 1947, the result of the UKUSA treaty signed by

the governments of the United States, the United Kingdom,

Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

The purpose of the UKUSA agreement was to create a single vast

global intelligence organization sharing common goals and a

common agenda, spying on the world and sharing the data. The

uniformity of operation is such that NSA operatives from

Fort

Meade could work from Menwith Hill to intercept local

communications without either nation having to formally approve

or disclose the interception.

ECHELON intercept station at Menwith Hill, England.

What is ECHELON used for?

In the days of the cold war, ECHELON’s primary purpose was to

keep an eye on the U.S.S.R. In the wake of the fall of the

U.S.S.R. ECHELON justifies it’s continued multi-billion dollar

expense with the claim that it is being used to fight

"terrorism", the catch-all phrase used to justify any and all

abuses of civil rights.

With the exposure of the APEC scandal, however, ECHELON’s

capabilities have come under renewed scrutiny and criticism by

many nations. Although not directly implicated in the bugging of

the Asia Pacific Economic Conference in Seattle, the use of so

many U.S. Intelligence agencies to bug the conference for the

purpose of providing commercial secrets to DNC donors raised the

very real possibility that ECHELON’s all-hearing ears were

prying corporate secrets loose for the advantage of the favored

few.

Given that real terrorists and drug runners would always use

illegal cryptographic methods anyway, the USA led attempt to ban

strong crypto to the general populace seemed geared towards

keeping corporate secrets readable to ECHELON, rather than any

real attempt at crime prevention.

The cover blows off!

Even close allies do not like it when they are being spied on.

Especially if the objective is not law enforcement but corporate

shenanigans to make rich politicians just that much richer. So,

the Civil Liberties Committee of the European Parliament looked

into ECHELON, and officially confirmed it’s existence and

purpose.

Here is the article that

ran in the London Telegraph

Tuesday 16 December 1997

Issue 936

Spies like US

A European Commission report warns

that the United States has developed an extensive network spying

on European citizens and we should all be worried. Simon Davies

reports:

Cooking up a charter for snooping

A GLOBAL electronic spy network that can eavesdrop on every

telephone, email and telex communication around the world will

be officially acknowledged for the first time in a European

Commission report to be delivered this week.

The report -

Assessing the Technologies of Political Control -

was commissioned last year by the Civil Liberties Committee of

the European Parliament. It contains details of a network of

American-controlled intelligence stations on British soil and

around the world, that "routinely and indiscriminately" monitor

countless phone, fax and email messages.

It states:

"Within Europe all email

telephone and fax communications are routinely intercepted

by the United States National Security Agency transferring

all target information from the European mainland via the

strategic hub of London then by satellite to Fort Meade in

Maryland via the crucial hub at Menwith Hill in the North

York moors in the UK."

The report confirms for the first

time the existence of the secretive ECHELON system.

Until now, evidence of such astounding technology has been

patchy and anecdotal. But the report - to be discussed on

Thursday by the committee of the office of Science and

Technology Assessment in Luxembourg - confirms that the citizens

of Britain and other European states are subject to an intensity

of surveillance far in excess of that imagined by most

parliaments. Its findings are certain to excite the concern of

MEPs.

"The ECHELON system forms part

of the UKUSA system (Cooking up a charter for snooping) but

unlike many of the electronic spy systems developed during

the Cold War, ECHELON is designed primarily for non-military

targets: governments, organizations and businesses in

virtually every country.

"The ECHELON system works by indiscriminately intercepting

very large quantities of communications and then siphoning

out what is valuable using artificial intelligence aids like

MEMEX to find key words".

According to the report, ECHELON

uses a number of national dictionaries containing key words of

interest to each country.

For more than a decade, former agents of US, British, Canadian

and New Zealand national security agencies have claimed that the

monitoring of electronic communications has become endemic

throughout the world. Rumors have circulated that new

technologies have been developed which have the capability to

search most of the world’s telex, fax and email networks for

"key words". Phone calls, they claim, can be automatically

analyzed for key words.

Former signals intelligence operatives have claimed that spy

bases controlled by America have the ability to search nearly

all data communications for key words. They claim that ECHELON

automatically analyses most email messaging for "precursor" data

which assists intelligence agencies to determine targets.

According to former Canadian Security Establishment agent Mike

Frost, a voice recognition system called Oratory has been used

for some years to intercept diplomatic calls.

The driving force behind the report is

Glyn Ford, Labour MEP for

Greater Manchester East. He believes that the report is crucial

to the future of civil liberties in Europe.

"In the civil liberties committee we spend a great deal of time

debating issues such as free movement, immigration and drugs.

Technology always sits at the centre of these discussions. There

are times in history when technology helps democratize, and

times when it helps centralize. This is a time of

centralization. The justice and home affairs pillar of Europe

has become more powerful without a corresponding strengthening

of civil liberties."

The report recommends a variety of measures for dealing with the

increasing power of the technologies of surveillance being used

at Menwith Hill and other centers. It bluntly advises:

"The

European Parliament should reject proposals from the United

States for making private messages via the global communications

network (Internet) accessible to US intelligence agencies."

The report also urges a fundamental review of the involvement of

the American NSA (National Security Agency) in Europe,

suggesting that their activities be either scaled down, or

become more open and accountable.

Such concerns have been privately expressed by governments and

MEPs since the Cold War, but surveillance has continued to

expand. US intelligence activity in Britain has enjoyed a steady

growth throughout the past two decades. The principal motivation

for this rush of development is the US interest in commercial

espionage. In the Fifties, during the development of the

"special relationship" between America and Britain, one US

institution was singled out for special attention.

The NSA, the

world’s biggest and most powerful signals

intelligence organization, received approval to set up a network

of spy stations throughout Britain. Their role was to provide

military, diplomatic and economic intelligence by intercepting

communications from throughout the Northern Hemisphere.

The

NSA is one of the shadowiest of the US intelligence

agencies. Until a few years ago, it existence was a secret and

its charter and any mention of its duties are still classified.

However, it does have a Web site (www.nsa.gov:8080) in which it

describes itself as being responsible for the signals

intelligence and communications security activities of the US

government.

One of its bases, Menwith Hill, was to become the biggest spy

station in the world. Its ears - known as radomes - are capable

of listening in to vast chunks of the communications spectrum

throughout Europe and the old Soviet Union.

In its first decade the base sucked data from cables and

microwave links running through a nearby Post Office tower, but

the communications revolutions of the Seventies and Eighties

gave the base a capability that even its architects could

scarcely have been able to imagine. With the creation of

Intelsat and digital telecommunications, Menwith and other

stations developed the capability to eavesdrop on an extensive

scale on fax, telex and voice messages. Then, with the

development of the Internet, electronic mail and electronic

commerce, the listening posts were able to increase their

monitoring capability to eavesdrop on an unprecedented spectrum

of personal and business communications.

This activity has been all but ignored by the UK Parliament.

When Labour MPs raised questions about the activities of the NSA,

the Government invoked secrecy rules. It has been the same for

40 years.

Glyn Ford hopes that his report may be the first step in a long

road to more openness.

"Some democratically elected body should

surely have a right to know at some level. At the moment that’s

nowhere".

Copyright Telegraph Group Limited 1997. Terms & Conditions of

reading.

Information about Telegraph Group Limited and Electronic

Telegraph.

"Electronic Telegraph" and "The Daily Telegraph" are trademarks

of Telegraph Group Limited.

These marks may not be copied or

used without permission.

Information for webmasters linking to

Electronic Telegraph.

FROM

"COVERT ACTION" QUARTERLY

EXPOSING THE GLOBAL SURVEILLANCE

SYSTEM

by Nicky Hager

IN THE LATE 1980S, IN A DECISION

IT PROBABLY REGRETS, THE US PROMPTED NEW ZEALAND TO JOIN A NEW

AND HIGHLY SECRET GLOBAL INTELLIGENCE SYSTEM. HAGER’S

INVESTIGATION INTO IT AND HIS DISCOVERY OF THE ECHELON

DICTIONARY HAS REVEALED ONE OF THE WORLD’S BIGGEST, MOST CLOSELY

HELD INTELLIGENCE PROJECTS. THE SYSTEM ALLOWS SPY AGENCIES TO

MONITOR MOST OF THE WORLD’S TELEPHONE, E-MAIL, AND TELEX

COMMUNICATIONS.

For 40 years,

New Zealand’s largest intelligence agency, the

Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) the nation’s

equivalent of the US National Security Agency (NSA) had been

helping its Western allies to spy on countries throughout the

Pacific region, without the knowledge of the New Zealand public

or many of its highest elected officials. What the NSA did not

know is that by the late 1980s, various intelligence staff had

decided these activities had been too secret for too long, and

were providing me with interviews and documents exposing New

Zealand’s intelligence activities. Eventually, more than 50

people who work or have worked in intelligence and related

fields agreed to be interviewed.

The activities they described made it possible to document, from

the South Pacific, some alliance-wide systems and projects which

have been kept secret elsewhere. Of these, by far the most

important is ECHELON.

Designed and coordinated by

NSA, the ECHELON system is used to

intercept ordinary e-mail, fax, telex, and telephone

communications carried over the world’s telecommunications

networks. Unlike many of the electronic spy systems developed

during the Cold War, ECHELON is designed primarily for

non-military targets: governments, organizations, businesses,

and individuals in virtually every country. It potentially

affects every person communicating between (and sometimes

within) countries anywhere in the world.

It is, of course, not a new idea that intelligence organizations

tap into e-mail and other public telecommunications networks.

What was new in the material leaked by the New Zealand

intelligence staff was precise information on where the spying

is done, how the system works, its capabilities and

shortcomings, and many details such as the codenames.

The

ECHELON system is not designed to eavesdrop on a particular

individual’s e-mail or fax link. Rather, the system works by

indiscriminately intercepting very large quantities of

communications and using computers to identify and extract

messages of interest from the mass of unwanted ones. A chain of

secret interception facilities has been established around the

world to tap into all the major components of the international

telecommunications networks. Some monitor communications

satellites, others land-based communications networks, and

others radio communications. ECHELON links together all these

facilities, providing the US and its allies with the ability to

intercept a large proportion of the communications on the

planet.

The computers at each station in the ECHELON

network

automatically search through the millions of messages

intercepted for ones containing pre-programmed keywords.

Keywords include all the names, localities, subjects, and so on

that might be mentioned. Every word of every message intercepted

at each station gets automatically searched whether or not a

specific telephone number or e-mail address is on the list.

The thousands of simultaneous messages are read in "real time"

as they pour into the station, hour after hour, day after day,

as the computer finds intelligence needles in telecommunications

haystacks.

SOMEONE IS LISTENING

The computers in stations around the globe are known, within the

network, as the ECHELON Dictionaries. Computers that can

automatically search through traffic for keywords have existed since

at least the 1970s, but the ECHELON system was designed by NSA to

interconnect all these computers and allow the stations to function

as components of an integrated whole. The NSA and GCSB are bound

together under the five-nation UKUSA signals intelligence agreement.

The other three partners all with equally obscure names are:

-

the

Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in Britain

-

the

Communications Security Establishment (CSE) in Canada

-

the

Defense Signals Directorate (DSD) in Australia

The alliance, which grew from cooperative efforts during World War

II to intercept radio transmissions, was formalized into the UKUSA

agreement in 1948 and aimed primarily against the USSR. The five UKUSA agencies are today the largest intelligence organizations in

their respective countries. With much of the world’s business

occurring by fax, e-mail, and phone, spying on these communications

receives the bulk of intelligence resources. For decades before the

introduction of the ECHELON system, the UKUSA allies did

intelligence collection operations for each other, but each agency

usually processed and analyzed the intercept from its own stations.

Under ECHELON, a particular station’s Dictionary computer contains

not only its parent agency’s chosen keywords, but also has lists

entered in for other agencies. In New Zealand’s satellite

interception station at Waihopai (in the South Island), for example,

the computer has separate search lists for the NSA, GCHQ,

DSD, and

CSE in addition to its own. Whenever the Dictionary encounters a

message containing one of the agencies’ keywords, it automatically

picks it and sends it directly to the headquarters of the agency

concerned. No one in New Zealand screens, or even sees, the

intelligence collected by the New Zealand station for the foreign

agencies. Thus, the stations of the junior UKUSA allies function for

the NSA no differently than if they were overtly NSA-run bases

located on their soil.

The first component of the ECHELON network are stations specifically

targeted on the international telecommunications satellites (Intelsats)

used by the telephone companies of most countries. A ring of

Intelsats is positioned around the world, stationary above the

equator, each serving as a relay station for tens of thousands of

simultaneous phone calls, fax, and e-mail. Five UKUSA stations have

been established to intercept the communications carried by the

Intelsats.

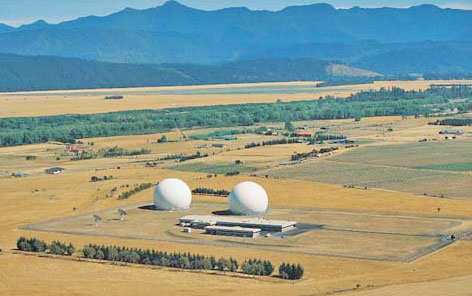

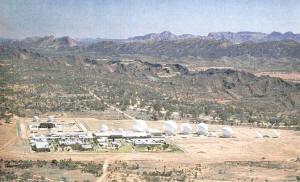

ECHELON Station in

Morwenstow, UK

The British GCHQ station is located at the top of high cliffs above

the sea at Morwenstow in Cornwall. Satellite dishes beside sprawling

operations buildings point toward Intelsats above the Atlantic,

Europe, and, inclined almost to the horizon, the Indian Ocean. An

NSA station at Sugar Grove, located 250 kilometers southwest of

Washington, DC, in the mountains of West Virginia, covers Atlantic Intelsats transmitting down toward North and South America. Another

NSA station is in Washington State, 200 kilometers southwest of

Seattle, inside the Army’s Yakima Firing Center. Its satellite

dishes point out toward the Pacific Intelsats and to the east. *1

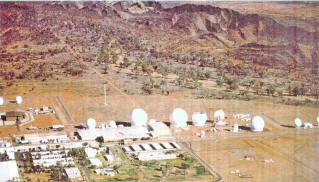

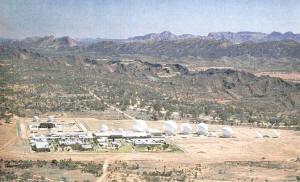

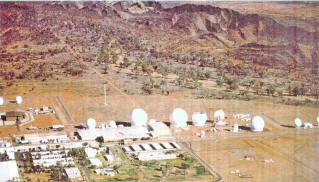

The job of intercepting Pacific Intelsat communications that cannot

be intercepted at Yakima went to New Zealand and Australia. Their

South Pacific location helps to ensure global interception. New

Zealand provides the station at Waihopai

(above image) and Australia supplies the

Geraldton station (below image) in West Australia (which targets both Pacific and

Indian Ocean Intelsats). *2

Each of the five stations’ Dictionary computers has a codename to

distinguish it from others in the network. The Yakima station, for

instance, located in desert country between the Saddle Mountains and

Rattlesnake Hills, has the COWBOY Dictionary, while the Waihopai

station has the FLINTLOCK Dictionary. These codenames are recorded

at the beginning of every intercepted message, before it is

transmitted around the ECHELON network, allowing analysts to

recognize at which station the interception occurred.

New Zealand intelligence staff has been closely involved with the

NSA’s Yakima station since 1981, when NSA pushed the GCSB to

contribute to a project targeting Japanese embassy communications.

Since then, all five UKUSA agencies have been responsible for

monitoring diplomatic cables from all Japanese posts within the same

segments of the globe they are assigned for general UKUSA

monitoring.3 Until New Zealand’s integration into ECHELON with the

opening of the Waihopai station in 1989, its share of the Japanese

communications was intercepted at Yakima and sent unprocessed to the

GCSB headquarters in Wellington for decryption, translation, and

writing into UKUSA-format intelligence reports (the NSA provides the

codebreaking programs).

click image to

enlarge

COMMUNICATION"

THROUGH SATELLITES

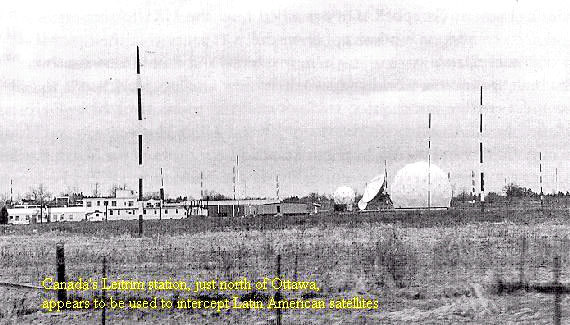

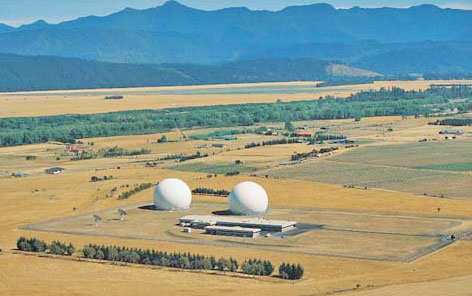

The next component of the ECHELON system intercepts a range of

satellite communications not carried by Intelsat. In addition to the

UKUSA stations targeting Intelsat satellites, there are another five

or more stations homing in on Russian and other regional

communications satellites. These stations are:

-

Menwith Hill in

northern England

-

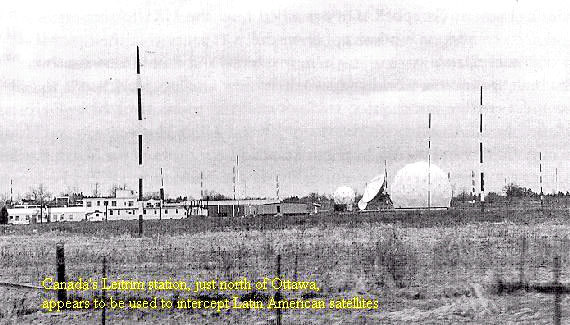

Shoal Bay, outside Darwin in northern Australia

(which targets Indonesian satellites)

-

Leitrim, just south of Ottawa

in Canada (which appears to intercept Latin American satellites -

below image)

-

Bad Aibling in Germany

-

Misawa in northern Japan

A group of facilities that tap directly into land-based

telecommunications systems is the final element of the ECHELON

system. Besides satellite and radio, the other main method of

transmitting large quantities of public, business, and government

communications is a combination of water cables under the oceans and

microwave networks over land. Heavy cables, laid across seabeds

between countries, account for much of the world’s international

communications. After they come out of the water and join land-based

microwave networks they are very vulnerable to interception.

The

microwave networks are made up of chains of microwave towers

relaying messages from hilltop to hilltop (always in line of sight)

across the countryside. These networks shunt large quantities of

communications across a country. Interception of them gives access

to international undersea communications (once they surface) and to

international communication trunk lines across continents. They are

also an obvious target for large-scale interception of domestic

communications.

Because the facilities required to intercept radio and satellite

communications use large aerials and dishes that are difficult to

hide for too long, that network is reasonably well documented. But

all that is required to intercept land-based communication networks

is a building situated along the microwave route or a hidden cable

running underground from the legitimate network into some anonymous

building, possibly far removed. Although it sounds technically very

difficult, microwave interception from space by United States spy

satellites also occurs.4 The worldwide network of facilities to

intercept these communications is largely undocumented, and because

New Zealand’s GCSB does not participate in this type of

interception, my inside sources could not help either.

NO ONE IS SAFE

FROM A MICROWAVE

A 1994 exposé of the Canadian UKUSA agency,

Spyworld, co-authored by

one of its former staff, Mike Frost, gave the first insights into

how a lot of foreign microwave interception is done (see p. 18). It

described UKUSA "embassy collection" operations, where sophisticated

receivers and processors are secretly transported to their

countries’ overseas embassies in diplomatic bags and used to monitor

various communications in foreign capitals. *5

Since most countries’ microwave networks converge on the capital

city, embassy buildings can be an ideal site. Protected by

diplomatic privilege, they allow interception in the heart of the

target country. *6 The Canadian embassy collection was requested by

the NSA to fill gaps in the American and British embassy collection

operations, which were still occurring in many capitals around the

world when Frost left the CSE in 1990. Separate sources in Australia

have revealed that the DSD also engages in embassy collection.

*7 On

the territory of UKUSA nations, the interception of land-based

telecommunications appears to be done at special secret intelligence

facilities. The US, UK, and Canada are geographically well placed to

intercept the large amounts of the world’s communications that cross

their territories.