We shall now proceed to explain the shape and the formation of the earth which has resulted from the evolution of our planet from the nebula, a shape which we are quite ready to understand after our study of Mars and the other planets. For convenience of description we have assumed certain measurements to be true. Of course we do not pretend that we have actually made these measurements, for no one is yet in a position to make them. But basing them upon the relative proportions of the polar cap of Mars and upon other considerations, we put them forward as the most likely approximations. The polar openings then, we should put at not less than 1400 miles across in each case. And it is probable that the crust of the earth is 800 miles thick. This means that when a ship sails over the lip of the polar orifice it is sailing over what may be compared to the circumference of a circle whose diameter is 800 miles. That means that the curvature would be just as imperceptible as the ordinary curvature of the surface of the earth--which indicates how absurd are some of the notions which our critics have of the nature of the aperture. The interior sun may be supposed to be 600 miles in diameter, so that the distance

between it and any point on the inner surface which it warms is 2900 miles, and these figures added give us 8,000 miles which, as we know, is the diameter of the earth.

Now if we asserted that this was the shape of the earth and had no evidence drawn from other planets or from polar exploration, we should be laughed at but the laughter would come from two sets of people each one of which may also laugh at the other set. So, if they disagree among themselves it looks all the more likely that neither may be right.

These people are the old fogies who believe that the earth is a solid shell enclosing a vast seething mass of molten matter which occasionally breaks out of the shell in the form of volcanoes, and the newer thinkers who claim that the earth is the most rigid of solids it is possible to conceive. 'We shall now proceed to show how both of these theories fail.

Of the old liquid-interior people it is not necessary to say very much. Their day is over. Scientists no longer put any credence in that notion--it is only in school books that it survives. If the earth had been a thin shell over a liquid interior it never would have survived in the form which these people allege. For just as the moon attracts the tides of the water on the surface, so it would have attracted the

liquid interior which would have pushed through the crust at whatever point the moon happened to be, as fast as that crust was formed.

What, then, says the reader, causes volcanoes and earthquakes? Let us ask the scientists. In Edwin S. Grew's, "The Romance of Modern Geology," we are told that the earth is continually indulging in small shivers--a thing which can much more easily be explained on out theory than if we suppose it to be a rigid solid. These are probably due to the fact that the crust is seamed with great cracks, and occassionally there is a sort of cave-in which will send a tremor throughout the whole shell. When these cracks are on a very large scale we get a chain of volcanoes as is the case in South America. Here is what Grew says about it:

"The volcanoes of the great chains of the Andes lie along a straight crack reaching from Southern Peru to Terra del Fuego, 2500 miles in length. The volcanoes of the Aleutian islands lie along a curved track equally long. Other shorter lines of volcanoes are very numerous, and since countless others existed in former times the cracks in the earth's crust must be exceedingly numerous. There is one crack which comes to the surface in various places in Eastern Asia and Western Africa, and stretching from the Dead Sea to Lake Nyassa, reaches the enormous length of 3500 miles."

Now it is obvious that with such surface flaws as that, a molten interior would break through upon any such attraction as that of the moon, and if the break once started it would extend all along those vast territories just mentioned.

That both earthquakes and volcanoes are phenomena of the surface of the earth only and do not go deep, is further shown by Mr. Grew in the volume from which we have already quoted. Many of them he lays to the existence of what are called, in England, "pot-holes," which are deep and ramifying caverns in the earth which may extend to a depth of nearly a thousand feet, disclosing to the explorer vast chambers hundreds of feet high, connected by smaller passages. Obviously where the earth is thus honeycombed a subterranean landslide may take place at any time, due, perhaps, to water erosion in the caverns, and the result would be a local earthquake.

It is also interesting to note that, if the earth were a thin crust covering a center of molten lava, in any earthquake or volcano in which that lava came to the surface, the solid rocks of the surface being heavier than the molten material, would sink until they came to rest at the center, and this process would soon eat up the whole surface of the earth, and that

process would have begun to take place as soon as the earth began to cool. For as soon as any part of the crust solidified it would sink. It is impossible to suppose that the whole exterior of the earth solidified at one moment and so imprisoned forever the molten material underneath. But merely to state this theory is to show how ridiculous it is. As one critic puts it:

"These savants have managed somehow to keep those raging fires burning from the very earliest periods of even the sun's history, without any abatement or cessation, and they tell us it is now raging with inconceivable fury in the bowels of our own earth and within all the planets, and, in accordance with their ideas, it seems likely to continue burning on forever. They conclude by computation that this fire occupies more than thirty-five out of thirty-six parts of this globe, and in some inexplicable manner, they have been enabled to keep this positive element in active operation, without furnishing one particle of combustible material to replenish its exhausted resources. This, we must admit, is the most astounding feat that philosophy has ever performed in the whole range of celestial and terrestrial mechanics, if it has been successfully accomplished."

And here is a point which renders the igneous theory of the earth's interior quite unnecessary to account for volcanoes:

"Professor Denton remarks that . . . coal may exist in layers or stratifications alternately with shales

and underclays for 'more than eight miles,' or even a greater distance. Now, if we look about us we think we may find a sufficiency of explosive and combustible materials, to produce all those volcanic and thermal phenomena, without resorting to a vast interior fire globe for the original cause."

That volcanoes are purely surface manifestations is shown by the fact that on many occasions it has been proved that the cause of a volcanic eruption was the access of sea water through one or more fissures to the hot base of the mountain. The proof of this is the presence of compounds formed by the salt of the sea water in the lava which was ejected.

But nowadays the scientists themselves admit that this igneous theory is an impossible one. Grew, in his "The Romance of Modern Geology," in fact, gives the whole case away when he says:

"The earth is not so solid as it looks and not so solid as it feels."

And furthermore he supports us in what we have said of the impossibility of a molten interior being held in by a crust:

"For that would leave a molten ocean more than 7900 miles across any way in which it was measured: 7900 miles deep, 7900 miles broad, 7900 miles long if we take 8000 miles to be the diameter of the earth. We all know what great tides the sun and moon by

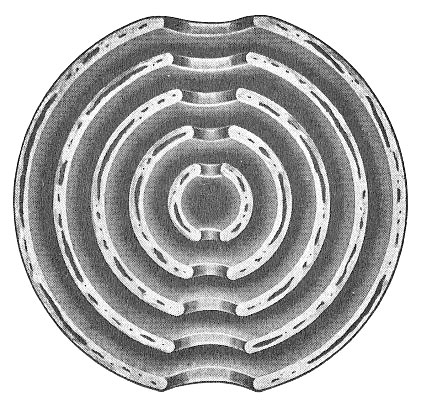

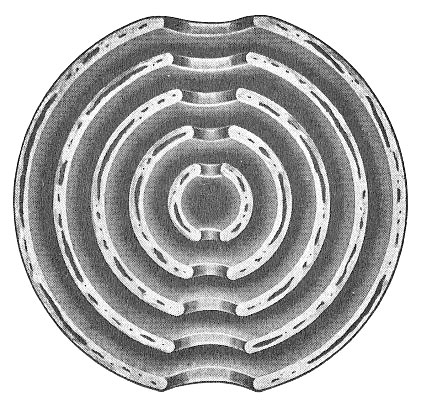

As so many people have thought our theory was in some way like that of Symmes we present herewith a diagram of the sort of earth that Symmes supposed to be under our feet. A study of this diagram will show at once the absurdity of thinking our theory is in any way like Symmes'. Each of the five shells represented above is, according to Symmes, revolving on its own axis at a rate differing from the rate at which any other shell is revolving. In the interior of each individual shell there are great hollow spaces or cavities and in each of these large spaces there is life, as well as there being life on the surface of each of the shells. Besides these immense spaces in each shell there are smaller spaces or gas pockets. And it should be noticed that on Symmes' theory there is no central sun. And as there is no central sun there can be no light in the interior except the very little that reaches the outer surface of the spheres by filtering through the openings from the outer sun. Not only would that he a very inadequate amount of light and heat--not enough to maintain life, but there is absolutely no provision at all for lighting the inner spaces or cavity of the spheres--although Symmes claims they are inhabited. We simply ask the reader to imagine such a collection of whirling spheres, each with its great hollows which can neither he entered or left, and yet each supporting life, and put to himself the question how such a conglomeration as that could ever be evolved from a nebula. And yet some people read about our theory and then state that our theory is related to Symmes' ideas. How absurd.

their attractions raise in the earth's outer ocean of water. Think what tides they would raise in this inner ocean of molten rock and metal. The earth's crust would not be able to hold such tides in. The molten stuff would always be breaking through the flimsy thirty miles of outer solid rock as if it were egg-shell. Twice a day there would be outbreaks of lava vast enough to submerge continents."

He then quotes Lord Kelvin to the effect that the heat of the earth's crust does not continue the further down we go, as had always been supposed, but that that increase only holds for a short distance, and then ceases. And then what?

Grew does not know, and the scientists don't know, but Grew does make this very significant confession:

"We know that the earth cannot be solid all through because it does not weigh enough." He then gives a number of conflicting theories as to what is to be found in the further interior--whether solids, liquids or gases. The fact that scientists conflict at this point shows that they have not sufficient data to build a consistent theory that will not conflict with the facts. And they never will be able to reconcile their conflicting views until they accept all the evidence--and that has been given for the first time in the present book.

Now as a matter of fact the actual observations made by scientists contradict both the usual scientific theories. We have spoken of the idea that the earth is molten in its interior. When we say that one writer in the Scientific American Supplement for January, 1909, lays it down as proven that the crust of the earth is so thin that it can only be called a "scum" formed by the oxidizing of the metals and other elements of the earth--just as a scum of oxide is formed when air comes in contact with the surface of molten lead. When this scientist claims, furthermore, that this scum is only twenty miles in depth, the reader will readily see how ridiculous the idea is on the face of it. As we have said, the attraction of the moon for the molten tides underneath would burst that scum as fast as it could form. It was the recognition of such absurdity that threw scientific opinion over to the other extreme--to-wit, that the earth was a very rigid solid.

Of course there are varieties of this theory. One variety is that which says that the earth was once molten but is now entirely solid. But some scientists hold another variety of the theory: that the earth never was molten. Dr. Arthur Holmes who has analyzed rocks and meteors for their radium content thinks that the earth as a whole never was molten but that

when it was a nebulous gas it attracted and caught what he calls "planetesimals"--which were solid, and so built itself up. Probably, dear reader, you did not know that scientists disagreed among themselves to that extent, did you?

In fact scientists have been so puzzled because their observations of the behavior of the earth's crust under various strains and attractions, did not agree with their theories that, some years ago, the celebrated Professor Geikie, one of the world's greatest geologists, was forced to admit that the problems arising from consideration of the evolution of the surface of the earth were still in a state where no solution was visible. And to escape the difficulties propounded by Professor Geikie, Professors Le Conte and Shaller suggested that the earth was neither a solid spheroid nor a shell with a liquid interior but that it consisted of an outer, solid crust, then, inside of that, a liquid or viscous stratum, and then a solid core inside of that again. 'What strange theories the scientists are reduced to when they ignore the facts!

As for the theory that the earth is a solid, rigid body with its rigidity equal to that of steel,. here is what Dr. N. Hertz has to say about the idea:

"All the calculations which give the earth a rigidity as high as that of steel are based upon the erroneous assumption that the great pressure existing in

the interior of the earth (the pressure at the earth's center is estimated to be about three and one-fourth million atmospheres) is a true measure of the rigidity of the earth. This is as incorrect as an assumption that the pressure of 800 atmospheres which exists at the sea bottom, five miles below the surface, is a true measure of the rigidity of the water at that point. In either case the pressure is the hydrostatic pressure due to the weight of the mass above, and the comparatively very thin solid crust of the earth is as susceptible to deformation by centrifugal forces as a shell of solid elastic material, sixteen inches in diameter and 1-30th of an inch thick would be."

Here we see is more contradiction. We agree with Dr. Herz that it is absurd to speak of the enormous pressure down at the center of the earth. But the earth is certainly not to be compared to his globe full of water--that we have already shown.

While, then, these scientific theories all conflict, what scientifically observed facts are there that will help us to the true solution?

Let us ask those scientists who have been observing instead of theorizing.

First we will call to the witness stand Professor A. E. H. Love who wrote for the Science Progress, Volume of 1912, a review of the third edition of Sir G. H. Darwin's book, "The Tides and Kindred Phenomena

of the Solar System." He notes that Sir G. H. Darwin is the world's greatest authority on this subject and he also notes that in this third edition of his celebrated book one-quarter is either added or rewritten--showing that what seemed true only a few years ago has been superseded by new ideas. This ought to warn us against the dogmatism of clinging to the older ideas about the earth's constitution. For this book in the reader's hands is simply a step in advance of the orthodox scientists of today, and tomorrow they may change their ideas and accept ours.

Now, as a result of his observations, Sir G. H. Darwin comes to the conclusion that:

"The body of the earth, on which the oceans rest, cannot be absolutely rigid. No body is. It must be deformed more or less by the attractions of the Sun and Moon." So he will try, he says, to find out just how those changes can be observed. His first attempt was to find out the "actual height of the so-called fortnightly tide." By fortnightly tide is meant "a minute inequality in the tide-height, having a period of about a fortnight, depending upon the inclination of the moon's orbit to the plane of the equator. . . Now the amount which the fortnightly oceanic tide would have if the Earth were absolutely rigid can be calculated." But the results show that the earth is not absolutely rigid and they also show that it is

not as far from rigid as it would be if it were a shell surrounding a liquid center. In other words the shape of the earth does yield to some extent under the force of the moon's attraction, and the yielding is not small enough to justify us in saying that the earth is practically rigid and it is not large enough to suggest that the earth is a viscous mass. The reviewer goes on to say:

"It is true that Lord Kelvin proved long ago that, if the earth were homogeneous and incompressible, it would have to be as rigid as steel to make the observable height of the fortnightly tide as much as that calculated from other data, before the actual observation was made." But, the reviewer goes on to say, other experiments show that the earth is not a rigid solid, among them being the experiments with a pendulum conducted by Prof. O. Hecker in Potsdam who showed that the actual movements of a pendulum, compared over a long time, are not as great as they would be if the earth were a solid body.

Now if the earth is not a solid, rigid body on the one hand or a shell-encrusted viscous or fluid body on the other hand and as we have seen scientists can prove neither the one thing nor the other--there is left only one possibility--that the earth is hollow, and that is the possibility which every page in this books shows to be the actuality.

And here are further scientific observations that make this more certain still, from the actual observation

of the earth itself. (For, of course, it is absolutely certain from the other standpoints already discussed.) The most interesting of these observations are along the line of earth tremors. Some of these observations were made as early as 1882 when a writer in the London Times described how he felt the earth shake when a party of friends were ascending a hill on whose crest he was lying at full length. This observation, he said, made him quite ready to understand the statements made by George H. Darwin--quoted above in another connection--and Horace Darwin, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science--when they described how the earth was in a constant state of tremor. Experiments carried on by the two brothers showed that the earth was in a constant condition of vibration, not discernible to us, of course, but clearly shown by the pendulum and other delicate apparatus by which the tremors were magnified and recorded. The writer goes on to say:

"When regular series of observations are made it is found that the pendulum is hardly ever steady. . . . Some days it may be more quiet than others and generally there is evidence of distinct diurnal periods, but the minor zig-zags constantly interrupt and sometimes reverse for an hour together the slower march northward or southward."

Now it is evident that a solid globe of great rigidity would not behave in this way, but if the reader remembers how a curved sounding board to a violin or other musical instrument vibrates he can easily see how the lunar, solar and other attractions bearing upon the earth and constantly changing--the earth tides in short--would cause just such tremors.

J. Milne, writing in Nature in 1894 also speaks of these and larger vibrations. He says:

"Earthquake observations, although still capable of yielding much that is new, are for the present relegated to a subordinate position, while the study of the tide-like movements of the surface of our earth, which have been observed in Japan and Germany, earth tremors and a variety of other movements, which we are assured are continually happening beneath our feet, are to take their place. Only in a few countries do earthquakes occur with sufficient frequency to make them worthy of serious attention. . . . The new movements to which we are introduced are occurring at all times and in all countries. . . . Great cities like London and New York are often rocked to and fro; but these world-wide movements which may be utilized in connection with the determination of physical constants relating to the rigidity of our planet's crust, because they are so gentle, have escaped attention.

"That the earth is breathing, that the tall buildings upon its surface are continually being moved to and fro, like the masts of ships upon an ocean, are, at present, facts which have received but little recognition. . . . It seems desirable that more should be done to advance our knowledge of the exact nature of all earth movements, by establishing seismological observations, or at least preventing those in existence from sinking into decay."

But the usual scientific theories to account for these tremors are very confused and contradictory. Thus Abbe T. H. Moreux, writing in Cosmos, 1907, says that the tremors which precede earthquakes travel through the earth so quickly that they must be generated under conditions which are not found in any solid. He then goes on to try to prove that the earth's interior is fluid but under exceedingly high pressure. He argues strenuously for this view, but as we have seen, it is an outworn view.

For instance, writing even before the scientist quoted above, a reviewer of scientific progress says:

"Gradually the very existence of the molten nucleus of our planet became more and more problematical. Already the mathematical investigations of Fourier and Poisson had shown that, owing to our

very imperfect knowledge of the physical aspects of the question, we are reduced to mere conjectures as regards the state of the inner parts of our globe. Later on the admirable investigations of Sir 'William Thomson, G. H. Darwin, Mellard Reade, Osmond Fisher, R. S. Woodward, and others rendered the existence of a molten nucleus surrounded by a thin, solid crust, less and less probable. And the geologist had to conclude that, as long as physics would not supply more reliable data for a mathematical investigation, he had better leave the question as to the physical state of the inner parts of the earth unsolved, and study the dynamic processes which are going on in the superficial layers of the planet."

Now if that is not a confession of the bankruptcy of orthodox science in this realm we do not know what would be so considered. The problem is frankly and totally given up. Does not that justify a man, who is not a scientist but who has observed the facts, to enter the field and propound a theory, especially when the theory shows just why the problem has to be given up by the scientists: because it concerns something which does not exist--the constitution of the material of the earth below the "superficial layers." That part of the earth is neither solid nor liquid because it is filled for the most part with the earth's atmosphere covering an earth surface very like our own.

Let us refer to one more point. Every reader is acquainted with the fact, as reported by miners and other observers, that the further one digs into the earth the hotter it gets. It was that idea that led people to believe that if they dug far enough they would come to a depth where it was so hot that everything would be in a molten condition. But that idea, too, must go, as being no longer in accordance with the evidence. Prof. Mohr of Bonn has written a very important paper on thermometric investigations of a 4,000 feet boring at Speremberg who finds that while there is an increase of temperature„ as we go down, the rate of that increase gets less and less all the time, so that soon it will be nil; that is to say there will no longer be any increase, and the point at which the heat would cease to increase would be about 13,550 feet.

Well, we could quote other scientists who disagree one with the other but it would simply be a repetition of what we have already said. So let us simply take their confessions of ignorance and ask them to investigate our claim to have dispelled that ignorance by a theory which cuts clear from all their contradictory ideas and goes to the root of the matter and is capable of the direct proof of observation.

Next: Chapter XIX. How Our Theory Differs From That of Symmes