|

Britain’s Secret War in Antarctica

Part 3

of 3

Extracted from Nexus Magazine

Volume 13, Number 1

(December 2005 - January 2006)

|

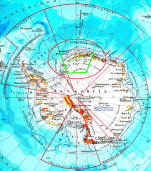

The Antarctica mystery

deepens as more details emerge about Norwegian, German,

British and American expeditions from the 1930s and

nuclear blasts over Queen Maud Land in the 1950s. |

Did

Britain Really "Miss the Bus" in Norway?

We are standing here in Norway,

undefeated, strong as before. No enemy has dared attack us. And

yet we, too, shall have to bow to the dictate of our enemy for

the benefit of the whole German cause. We trust we shall from

now on deal with men who respect a soldier’s honour.

— General Böhme, German Commander-in-Chief in Norway, 7

May 1945

The primary reasons for Norway’s

importance to Germany were that its coastlines made exceptional

U-boat bases, the Germans needed to secure shipments of Swedish iron

ore, and the Vermok hydro-electric plant, which produced deuterium

oxide (heavy water), was essential to their atomic research, in

which they were leading the world at that juncture. However, there

were other reasons—reasons that caused Hitler to review and reverse

his stance on preserving Norwegian neutrality.

On 14 January 1939, Norway formalized its claim to Queen Maud Land

in Antarctica, its course of action forced on it by the imminent

German discoveries. Adversely, for Norway, its attempt at

pre-empting any German claims failed, and so began a political

crisis that led to invasion. The Deutsche Antarktische Expedition,

using Norwegian maps, soon realized that the wily Norwegians had

omitted the vast, dry areas that it rediscovered on 20 January 1939.

The Norwegians, and also the British, had long been aware of

ice-free areas but had purposely omitted them on their maps so as to

avoid additional claimant countries appearing and the conceivable

diplomatic crises that would ensue.

When the Germans reported the ice-free areas, they were told to

claim the whole area in the name of Nazi Germany. They were ordered

to drop stakes with swastikas on them to state their intent for

sovereignty: this, the Nazis hoped, would be enough to formalize

their claim. Nazi Germany and Hitler cared little about what the

world thought: they had already gained Austria and Czechoslovakia,

and Antarctica was to be a further extension of the Third Reich.

Norway valiantly protested about the German claim and the renaming

of Queen Maud Land to Neuschwabenland but, with European nations

gearing up for war and the world’s attention turning to Poland,

Antarctica was forgotten.

When war finally broke out in September 1939, most of Germany’s

eventual conquests declared neutrality. Norway was no exception.

Hitler wanted Norway to remain neutral but his War Cabinet, whose

opinions he trusted until the tide turned against Germany, persuaded

him otherwise.

On 20 February 1940, Hitler ordered General von Falkenhorst to lead

an expedition force to Norway. Hitler claimed:

"I am informed that

the English intend to land there [Norway] and I want to be there

before them."32

The British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, famously boasted

when he announced that British forces had also landed in Norway that

Hitler had "missed the bus"33.

His folly caused his government to collapse, his resignation to be

forced and his reputation to be destroyed. Furthermore, by

committing troops to Norway, Chamberlain had played into the hands

of Hitler and all those inside the German War Cabinet. But had the

British mission been a total failure?

Operation Weserübung was launched by Germany on 9 April 1940 and

Norway was invaded (Denmark was also invaded that same day). And

though the British and Allied forces had to be evacuated in June,

they had slowed the unstoppable Wehrmacht enough to help the

monarchy, the government and the national treasure be evacuated on

board the British cruiser, HMS Devonshire. King Haakon VII

represented Norway in exile, and the vast treasures and documents

saved were beneficial not just to the preservation of Norway but to

British Intelligence.

Hitler was furious with Vidkun Quisling, whom he had hoped would aid

the Nazis more comprehensively. Quisling ultimately would have no

power, and his inability to stop the evacuation of the monarchy, the

government and not least the vast treasures and documentation caused

Hitler to lose faith in him and declare him a Norwegian traitor.

Those who failed Hitler lost their standing—Hitler made sure of

that. Even so, Quisling claimed publicly that he had been offered

"safe refuge". Whether the statement was that of a madman or was an

honest admission, it echoed the claims of others.

Though Hitler had only wished to beat the British to Norway, his War

Cabinet knew that Norway was vital to virtually all the branches of

Germany’s armed forces and was more beneficial to its war effort

than any other conquest. Nazi Germany’s occupation of Norway brought

immense benefits to the Reich. There were thousands of miles of

protected fjords for the German U-boats, and there was the

possibility of the Nazis exerting pressure on neutral Sweden.34

The Third Reich now had a border closer to the Arctic,35

and there was also the chance to train its soldiers in polar

conditions, especially after the acquisition of Spitzbergen,36

much to the pleasure of Himmler and his Ahnenerbe. Best of all,

Norway was within striking distance of all Nazi Germany’s enemies.

Norway and its ports also made marshalling the Arctic Sea and the

North Atlantic far more profitable. These benefits, allied with the

primary reasons, made Norway a highly prized conquest.

However, Germany’s occupation was not without problems. Britain

heavily financed the Norwegian Resistance and it was due to their

cooperation that the Vermok hydro-electric plant was targeted and

sabotaged so successfully.

Information was passed on a two-way basis and the SOE and SIS were

privy to any revelation uncovered. British Intelligence also had

access to all the Norwegian Government’s files, no matter how

"sensitive" the information. Britain at that point stood alone: any

information, no matter how trivial, was indispensable. Many Poles

had gone to the UK after the start of the German occupation with

intelligence on the Germans as well as with one of the first

prototypes of the Enigma code-making device. Similarly, with the

invasion and occupation of Norway, many fleeing Norwegians brought

secrets of the Reich to England.

After Britain frustrated Germany in the Battle of Britain and, as a

result, instilled hope in the numerous governments in exile, in

1940–41 it could only fight the Germans in Africa or bomb their

cities. But news was soon filtering through about a new front, and

one that both the British and Norwegian governments had hoped would

never be opened—a front for which there was little in the way of

contingency plans.

On 13 January 1941, German commandos under the leadership of Captain

Ernst-Felix Kruder from the commerce raider, the Pinguin, stormed

and violently captured two Norwegian whaling ships. If that had

happened around European coastlines, there would have been no

mystery because the Germans allowed none of its conquered peoples to

sail too far from land; but because the captures took place in the

Southern Ocean off Neuschwabenland, the news when it filtered

through could only have sent shock waves through both the British

and Norwegian governments. However, the mystery deepened further

because the subsequent night the German commandos resurfaced and

captured three more whaling ships and also 11 catchers.

The German Antarctic Fleet was active and prospering—mines they had

laid around Australian ports sank the first US vessel lost to enemy

action—but it was the Antarctic coast and islands where they mainly

loitered. The Atlantis,37

the Pinguin,38 the

Stier39 and the Komet40

were just four of the documented ships that had anomalous reasons

for being so far south. All four were eventually sunk by the British

Navy, far from Antarctica in various parts of the world from France

to the Ascension Islands.

Now that the Antarctic Front had been truly opened, Britain

increased its Antarctic bases and personnel numbers and even issued

a postmark. However, possibly the most important area that demanded

a base was in Neuschwabenland, officially known as Queen Maud Land.

Through Norway’s assistance with information and maps, Britain

envisaged Maudheim as the most viable place for a base because it

was close enough to be able to spy on German activities and also was

within striking distance for a highly trained and disciplined

military unit. The seeds for the Neuschwabenland campaign had been

sown.

From 1941 until the start of the British–Swedish–Norwegian

Expedition of 1949–52, Britain sent at least 12 official missions to

Antarctica—half of them between the end of the war and the beginning

of

Operation Highjump, led by

Admiral Byrd, starting in December

1946.

Even more intriguingly, Britain sent no

missions from the commencement of Highjump until 1948, during which

time the US had Antarctica all to itself. Britain nonetheless was

more active in Antarctica during the 1940s than any other nation,

yet the only Antarctic mission mentioned in depth by historians is

Admiral Byrd’s. His mission still overshadows every other mission

and is the main focus of attention for many conspiracy theorists.

Britain’s exertions were and still are totally overlooked; and with

Admiral Byrd spreading misinformation, the true conspiracy

concerning Antarctica as a Nazi haven was forgotten.

After the German surrender, Norway still needed to be mopped up, the

possible Nazi exodus needed to be ascertained and the secrets that

Norway held still needed more investigation. The discoveries further

confirmed that the war had ended just in time, but suspicions were

still aroused about the estimated 250,000 missing German

personnel—including Martin Bormann and thousands of other wanted

Nazi war criminals. The enigma of the submarines that were presumed

to have been utilized in their escape also required consideration.

However, even though a percentage of Germany’s U-boats may have fled

Norway, what was uncovered was still intriguing and certainly proved

that the Germans had made great technological strides.

In June 1945, the Washington Post published an article stating that

the RAF had found, near Oslo, 40 giant Heinkel bombers—aircraft with

a 7,000-mile range. The article stated that the captured German

ground crews had claimed that,

"the planes were held in readiness for

a mission to New York".41

The British also requisitioned some of the U-boats held in Norway at

the end of the war, including the new Type XXI. Captain

Mervyn

Wingfield was placed in charge of taking these 25 salvaged U-boats

to Scapa Flow and, interestingly, chose the new Type XXI to sail in.

Upon returning, he stated that "the Allies had won the submarine war

just in time"42—a

statement reiterated by all the Allies when speaking about the

Nazis’ new weapons.

In the UK, British Intelligence unearthed more of Norway’s secrets

but suppressed them; Antarctica was no exception. When the Norwegian

Government returned to a liberated Norway, Antarctica soon returned

to their consciousness, though the Norwegians would have to wait

several years to go back there, lest the rumours of a Nazi base were

true.

On the other hand, Britain decided it had collated enough knowledge

about Antarctica to initiate an intense investigation—one that had

to dispel all fears and hide all evidence—for it could not tolerate

any more technology or personnel being acquired by the wrong hands,

namely, the USSR and the USA.

Britain had helped liberate Norway and, as 1945 was drawing to a

close, was in the process of "liberating" Queen Maud Land (the new

atlas of the post-war world no longer recognized Neuschwabenland).

However, the mysterious wartime expeditions conducted by all the

combatant countries, especially Germany, were not entered into the

World War II history books. A travesty of history had occurred.

Postwar

Power Plays

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, suspicions surfaced and

rumours spread, and the new enemy—one that Hitler had hoped to

annihilate—was communism. Allies became enemies, whilst former

enemies became allies in the battle against communism. And whilst

the USA was offering huge financial subsidies to Western governments

to keep them communism-free, Britain was left alone to clean up the

last remaining Nazi outposts.

When German forces surrendered in May 1945, peace should have broken

out but, alas, the world was thrown into a turmoil that was every

bit as volatile as it had been before the most violent war in

humanity’s history began. The year 1945 was not just the year that

World War II ended but also the year that the Cold War started in

earnest; and whilst the USSR and the USA had fears about each

other’s intentions, they also had differing ideas for how Germany

was to be administered. The problems started at the Yalta Conference

of 4–11 February 1945, but were heightened by the end of the war in

Europe when the misinformation and secrecy about the Allies’

discoveries made the partnership that had destroyed Nazism no longer

tenable.

The atmosphere that surrounded Germany in May 1945 following the

Nazi surrender was one of exhaustion; but whilst the Western Allies

were so fatigued by the war effort, Stalin was not going to give up

his territorial gains and was prepared for war and, indeed, fully

expected it. The Soviets did nothing to allay the fears that a Nazi

haven had been built or that Hitler might not have committed suicide

but, instead, had escaped.43

Just before Berlin fell to the Soviets, it was reported that Martin Bormann had discussed

Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, with Grand

Admiral Dönitz. This conversation that emanated from Hitler’s Berlin

bunker was one of the last to be intercepted in the war in Europe.

Argentina had long been perceived as a haven for many escaping

Nazis, but this possibility was long denied by the sympathetic

Peron. Yet, with the Soviet General Zhukov and Stalin disagreeing

as to whether Hitler was dead or had fled, the Nazi survival myth

gained momentum.

Britain, in the unique position of holding the strategically

important Falkland Islands, was the only country in the immediate

months after the war that was in a position to investigate the

leading Nazis’ claims about an Antarctic haven and the rise of a

Fourth Reich in South America.

The USA, distracted by the war against Japan and the brewing Cold

War, had been caught short by Britain’s Antarctic exertions and

humbled by its aggressive stance. So the Americans soon adopted a

policy, dreamt up during the war, that would destroy Britain’s

imperial aspirations, hinder every attempt by Britain to exert any

influence around the world and make the country an "ally" in name

only. However, as early as 1942, Britain and British identity were

suffering as a result of the United States’ globalization agenda. It

must be remembered that Britain was denied its own atomic bomb,

despite the fact that the bomb could have not been created without

British expertise. Furthermore, the British people faced worse

rationing than any other Western nation, lasting direfully until the

1950s, and Britain was also pressured into giving full independence

or self-government to most of the territories in its Empire.

So, whilst Britain went into World War II a superpower, by the end

of the war and by the actions of American foreign policy, especially

Operation Highjump, it had been put

firmly in its place. The United States became the only country that

could successfully influence Britain—as the 1956 Suez crisis proved.

Even now, 60 years after the end of World War II, British blood is

still being shed on behalf of US foreign policy.

Exploring Queen Maud Land

As discussed in part one, the Nazi "Shangri-La" did exist. Of

unknown size, it was set up during the 1938–39 Deutsche Antarktische

Expedition. The existence of a Nazi Antarctic base hidden in vast

caverns was considered feasible enough for

the British to set up

bases in many parts of Antarctica during the war in response to the

threat. And whilst the officially recorded British expeditions

mainly concentrated around the Antarctic Peninsula, those not

recorded were those that concentrated on investigating Queen Maud

Land—so named by Norwegian whalers prior to 1939 in honour of Queen

Maud of Norway (1869–1938), consort of King Haakon VII and formerly

Princess Maud of the United Kingdom, a granddaughter of Queen

Victoria. the British to set up

bases in many parts of Antarctica during the war in response to the

threat. And whilst the officially recorded British expeditions

mainly concentrated around the Antarctic Peninsula, those not

recorded were those that concentrated on investigating Queen Maud

Land—so named by Norwegian whalers prior to 1939 in honour of Queen

Maud of Norway (1869–1938), consort of King Haakon VII and formerly

Princess Maud of the United Kingdom, a granddaughter of Queen

Victoria.

The Norwegians began exploring Queen Maud Land intensively in 1930,

and using planes for the first time they photographed and sketched

the area. In subsequent flights in 1931 and 1936, they uncovered

areas unknown and identified anomalies that would attract worldwide

interest. On 4 February 1936, Lars Christensen dropped the Norwegian

flag from his plane, thus claiming the land informally. The maps

produced from the photographs omitted the dry areas and lakes that

had been identified, but the discoveries led to private discussions

between the Norwegian Government and the Monarchy as to whether

Norway should annex the area.

After much deliberation, on 14 January 1939—six days before the

first Deutsche Antarktische Expedition flight over Queen Maud

Land—the Norwegian Government passed a royal decree annexing the

region between Enderby Land and Coates Land as Queen Maud Land.

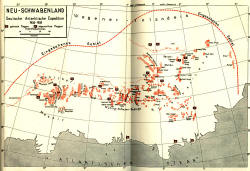

The Deutsche Antarktische Expedition discoveries were well

publicized. Captain Ritscher and his two Dornier Wal flying boats (Boreas

and Passat) flew extensively and produced in excess of 1,500

photographs that covered an area of over 250,000 square kilometers.

However, as with the strange case of the suppressed Norwegian maps,

most of the films, records and research materials were destroyed in

the war, though some have since resurfaced.

During the war and up till the end of the Antarctic summer of

1945–46, Britain’s RAF was also flying over Antarctica to map the

area and search for suitable places to establish bases. It

discovered more dry areas and possibly even the intelligence that

provoked Britain’s Neuschwabenland campaign.

Britain’s arrogance in committing troops to Antarctica, independent

of the United States, and in celebrating the feat with the release

in February 1946 of a provocative stamp set, would inevitably lead

to Britain’s claims on Antarctica being contested, even though the

stamps commemorated Britain’s final fight with Nazism rather than

being a statement of its Antarctic claims. And even though Britain

expressed outrage publicly when Highjump was launched, it was just a

pretence: privately, Britain knew that the USA’s newfound superpower

status meant that it would not permit Antarctica to be utilized by

other nations for financial gain.

Britain halted its Antarctic flights and operations for two years,

giving the United States a free hand in Antarctica with the

commencement of Operation Highjump. With the Nazi haven destroyed,

there was little need for the British to return: the Americans would

not discover anything that had not already been discovered. Or would

they?

In the two years they had to discover as much about Antarctica as

possible, the Americans found dry areas and warm-water lakes that

provoked immense media interest, but Operation Highjump, which

they’d planned to last for six months, ended after just eight weeks.

They received a hostile reaction from other nations, but it was only

after the mission’s return that the rumours and theories began to

abound and the enigma surrounding Highjump really began. The US

conducted another expedition, Operation Windmill, in the Antarctic

summer of 1947–48 and mapped additional areas of special interest.

The RAF returned in 1948–49 and flew extensively in search of a

viable base in Queen Maud Land for the joint Norwegian–

British–Swedish Expedition (NBSE) that was going to last from 1949

to 1952 and whose objective was to investigate and verify the 1938

German discoveries.

Britain and Norway knew that the area of Queen Maud Land which the

Nazis had utilized would be vastly different from that which was

mapped in the 1930s and early 1940s. An explosion of sufficient

magnitude could have created a warm front. The ground could have

warmed enough for rising heat to have created precipitation—how much

could only be gauged by the velocity of the explosion. In all

probability, snow would have fallen on areas that had not seen water

for thousands if not millions of years and the landscape would have

changed significantly.

When NBSE team members inspected the area, they found the largest

land animal (bar penguins) on the continent: tiny mites. That

discovery was an irregularity in itself. The expedition also

discovered unusual lichens and mosses in certain areas. However,

the

lakes that had been so prevalent in reports from previous

expeditions were largely not noted; nor were the vast, dry areas.

Could the lakes have frozen and the majority of the dry areas have

disappeared under a blanket of snow?

Meantime, more and more countries wanted their own bases in

Antarctica, and soon skirmishes started. In November 1948, Britain’s

Hope Base on the Antarctic Peninsula was suspiciously destroyed by

fire; in 1952, Argentinian forces shot at the British returning from

the joint expedition. Details of other skirmishes unfortunately have

been suppressed for diplomatic reasons.

However, in 1982, Britain went to war against Argentina over the

Falkland Islands (the Malvinas). Its defeat of the Argentinian

forces led to the collapse of the fascist military junta that had

dominated Argentina for several years. Argentina also had more than

a passing interest in Antarctica but, with the deaths of over 2,000

personnel in the Malvinas campaign and facing the possibility of

Buenos Aires being bombed, Argentina had no choice but to admit

defeat. Yet, whilst admitting the battle was lost, Argentina

insisted the war was not over. The Malvinas are Argentinian

possessions according to South American atlases, and who is to say

that war will not erupt again one day? If that were to happen,

Britain would again send an armada to fight because, quite patently,

the Falkland Islands are still one of Britain’s most prized

dependencies and the reason is quite simple: their close proximity

to Antarctica and all its treasures and mysteries that one day will

be allowed to be utilized and accessed.44

Military

Interest in Antarctica

Before the Antarctic Treaty was ratified on the 23 June 1961, the

International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1958 brought immense

international attention and cooperation to the frozen continent. The

Americans returned in numbers, as did the British, but the Soviets

also began their own experiments.

The aim of the IGY was to enable nations to put aside their claims

whilst sharing resources and scientific information. The success of

the IGY allowed the Antarctic Treaty to be enacted—but with the USSR

stating that it had no intention of leaving Antarctica and that it

would keep all its bases when the IGY ended. However, all claimants

deemed that "Antarctica is to be used for peaceful purposes only",

although military personnel and equipment may be utilized but not

for military reasons.

In the years prior to the June 1961 ratification, the USA, UK and

USSR had all used Antarctica for military purposes and all three

nations were rumoured to have tested nuclear bombs on the continent.

On 27 and 30 August and 6 September 1958, at least three such bombs

were detonated in Antarctica, allegedly by the Americans. Rumour has

it that they were set off in the area of Queen Maud Land and were

triggered 300 meters above the target, with the initial aim being to

"recover" frozen areas. The locations of other bomb detonation sites

have been firmly suppressed, but it is believed that the areas

reconnoitered by the Germans in 1939 and 1940 were targeted.45

With the Germans and Americans officially claiming to have found

warm-water lakes on their expeditions, it was only a matter of time

before more were discovered. One such lake, discovered by the

Russians, is Lake Vostok, which is 4,000 meters below the surface

and curiously is located under the Russian base camp of Vostok. News

of the discovery was not released to the world until 1989, so had

the Soviets found the subterranean lake years earlier and was this

their main reason for refusing to leave its base? The lake has still

not been investigated, mainly out of fear of what could be unleashed

and to avoid contamination of the lake, although a huge magnetic

anomaly has been identified.46

With so many lakes being discovered and with satellites proving that

the Antarctic is made up of huge, ice-encased archipelagos, is it

unimaginable to believe that a subterranean trench, wide enough for

U-boats to pass through, actually runs through Antarctica, as

claimed by author Christof Friedrich and on the

Piri Reis map?

If the Nazis had built a hidden base in Neuschwabenland and that

base had been destroyed in 1945, leaving only a few German Antarctic

outposts, then any evidence of a Nazi incursion on Antarctica would

have been destroyed comprehensively by the nuclear exertions of the

USA, USSR and UK. Nevertheless, rumours persist that the Nazis were

not totally destroyed in Antarctica but fled to secret bases in

South America.47

Britain’s Neuschwabenland Campaign Revisited

If British forces had indeed destroyed the Nazi outpost that was

rumoured to have existed amid the Mühlig-Hoffmann Mountains, this

would never be made public nor be given much credence by mainstream

historians. Even so, Britain was the nation most active in

Antarctica during the 1940s, which is intriguing if not suspicious.

Furthermore, Britain was privileged enough to have collated a mass

of evidence on German Antarctic intentions via the leading Nazis it

apprehended and via its efficient intelligence network and its own

field investigations. All of this leads one to the conclusion that

something significant must have occurred there, and it appears only

time will tell. Postwar scientific revelations suggest that

Antarctica was disrupted by human activity at some time in its near

past—a finding that may add credence to the likelihood of Britain’s Neuschwabenland campaign.

In 1999, a research expedition discovered a virus to which neither

animals nor humans are immune. Specialists were unable to explain

the source of the virus, though some tried. According to some

scientists, the virus could have been a prehistoric life-form that

had been preserved in the ice. However, other specialists speculated

that the virus could have been a secret biological weapon that had

been delivered to Antarctica during the 1938–39 Deutsche Antarktische Expedition. If a biological weapon or virus had been

taken to Antarctica, it is doubtful that it would have been

unleashed onto the continent intentionally, but, instead, stored

with extreme care. If the Germans really had been the architects of

the Antarctic virus and they had taken studious care of their

weapon, would it be too adventurous to think that the virus could

have been released by an attack of some degree on the very place

where it was stored?

Another mystery may be central to Queen Maud Land and what may have

happened in 1945. In 1984 the British Antarctic Survey, based at

Halley Station,48

noticed a hole in the ozone layer for the first time; it was located

over Queen Maud Land. Scientists, after much speculation, claimed

that the hole was due to CFCs and in time would increase global

warming. Could the hole, like the virus release, have been caused by

a huge explosion of nuclear proportions? With three known atomic

tests and a considerable number undisclosed associated with the

likely destruction of the Nazi base, it appears that the hole was

caused by more than just CFCs.

Subterranean lakes with signs of life, geothermally warmed lakes in

dry valleys in a supposed frozen wasteland, viruses that threaten

mankind, mysterious holes in the atmosphere allied with suppressed

military ventures may seem the work of fiction, and yet they are all

fact! Antarctica is a truly mysterious place, and that is why it is

inconceivable that the Nazis would claim an area and leave it

unoccupied and undefended, especially when the Channel Islands, for

instance, a strategically unimportant Nazi gain, utilized for its

defenses more than 10 per cent of all the concrete and iron that was

used in the construction of the Atlantic Wall—a wall that stretched

from the Pyrenées to the North Cape of Norway!

However, trying to validate the story of the British Neuschwabenland

campaign is slightly tougher to ascertain. Tales of Polar Men,

ancient tunnels and a decisive battle against remnants of the Third

Reich appear fanciful. Even so, it is widely known that Nazi

scientists were experimenting on men to simulate the freezing

conditions of the Eastern Front and to help their forces better deal

with them.49 Could

the heinous experiments have been a success of sorts, allowing

certain soldiers to combat the cold more efficiently?

Tales of ancient tunnels, even tunnels leading through the Mühlig-Hoffmann

Mountains, appear at first far-fetched, but would a cavern network,

glacially eroded enough, appear unnatural and thus be explained as a

tunnel? Soldiers are not scientists and see things as they

are—though whether it was a tunnel or a long cavern network that the

British had discovered, it ultimately led to a Nazi base. The base

could have been similar to the U-boat base that appeared in the film

Raiders of the Lost Ark, but that’s highly unlikely—but what isn’t

is the possibility that a base had been constructed and was being

manned by German forces. The British had secret wartime bases, so

why not the Nazis? It also must be remembered that some Japanese

soldiers fought on, not accepting defeat, for over 20 years,50

so why not pockets of Germans? In fact, Nazi Werewolves were active

after the May surrender, and isolated attacks occurred for a few

years after the war was deemed over and Nazism was thwarted.51

Whether the Neuschwabenland base was eradicated by Britain’s Special

Forces in 1945–46 or not, it is more than feasible that Britain

could have pulled off the feat. During the war, Britain had some of

the finest special forces personnel in the world, and still does

today, and they were expertly trained in sabotage and destruction,

using limited manpower in covert and inexpensive operations. They

were so successful that, even after the Dieppe fiasco, Hitler

ordered that any of them captured were to be summarily executed.

Britain, unlike the United States, believed that success is more

attainable with limited resources; however, with the US philosophy

of "might is right", it is no wonder that most attention paid to

Antarctic expeditions has been firmly focused on

Operation Highjump.52

Admiral Byrd’s statements and supposed discoveries, which have

spawned a multitude of conspiracy theories, overshadowed Britain’s

exertions comprehensively.

Whether the British mission did destroy the Nazi base, with any

remaining Nazis finally being expunged by the atomic force of the

wartime allies, is not the question that needs asking. What is,

though, is just how much of Antarctica’s past, present and, indeed,

its future has been, is being and will be suppressed.

Postscript: 1966 British Antarctic Survey Mystery

After the first part of Britain’s Secret War in Antarctica was

published,

I was inundated with people and specialists in their field with more

substantiating information. However, by far the most intriguing and

exciting was an email sent to me by Miles Johnston who

investigated a strange story about Antarctica with Danny Wilson

whilst with the Irish UFO Research Centre. The centre was contacted

by an Eric Wilkinson in 1975, who had reported a strange

incident in 1966 when he was with the British Antarctic Survey.

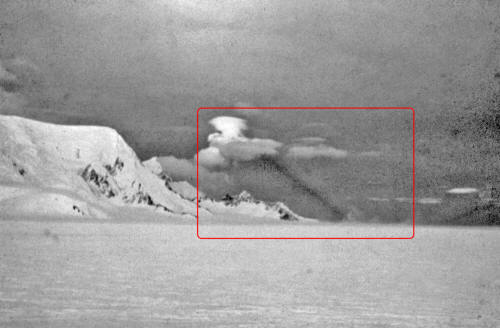

An even stranger photo backs up the story (see above). In Miles

Johnston’s own words, he explains:

"In 1975 I investigated a

UFO/Strange Black Ray Cloud formation, taken by a Belfast

member of the British Antarctic Survey. He gave me some images

of a pulsing cloud formation firing a black ray into the ice,

which bounced off and reflected further away from him. Who

knows... maybe someone down there is using negative energy beam

weapons? Or was... since the images were taken in 1966."

click image to

enlarge

The photo [above] is indeed enigmatic

and substantiates the fact that Antarctica and Britain’s role there

are shrouded in mystery.

Endnotes

32. Hart, Basil Liddell, History of

the Second World War, Cassell, London, 1970, p. 411.

33. Neville Chamberlain, Parliamentary Speech, 2 April 1940.

34. A total of 2,140,00 German soldiers and more then 100,000

German military railway carriages crossed Sweden until the

traverse was officially suspended on 20 August 1943.

35. The Nazis were fascinated by polar myths, and with the USSR

and the USA more accessible via the frozen Arctic Ocean and

Murmansk the only port available in Europe for the Soviet Union,

the Arctic convoys were constantly harassed, whilst scientific

studies increased in the Arctic.

36. Spitzbergen has numerous mysteries surrounding it, from

anomalous plant and animal fossils to ancient ruins. Many

believed it to be ancient Thule. Also, Spitzbergen cannot be

mentioned without the rumour concerning a UFO crash there in the

1950s; British scientists were supposedly involved in the

retrieval.

37. Atlantis had a name-change to Tamesis before being sunk by

HMS Devonshire near the Ascension Islands on 22 November 1941.

38. The Pinguin was sunk off the Persian Gulf by HMS Cornwall on

8 May 1941.

39. The Stier visited Antarctica and Kerguelen in 1942.

40. The Komet was sunk off Cherbourg in 1942 by a British

destroyer.

41. The Washington Post, 29 June 1945.

42. The Times, London, June 1945 (exact date not available).

43. An official Soviet statement released in September 1945

claimed that "mysterious persons were on board the submarine,

among them a woman..." With Stalin going on record with his view

that Hitler was alive, and contradictions coming from his own

generals, the USSR only added to the mystery.

44. A 50-year extension on the mining ban was agreed in 1998; it

runs until the year 2048.

45. Stevens, Henry, The Last Battalion and German Arctic,

Antarctic, and Andean Bases, The German Research Project,

Gorman, California, 1997.

46. Scientists, with NASA’s assistance, have drilled to within

500 metres of the lake. Russia recently declared that during the

Antarctic 2006–07 summer season it will drill into the lake.

47. Rumours that the Nazis built bases in the Andes and/or the

Amazon rainforest go hand in hand with stories that the Nazis

were in league with alien races and are definitely TBTBs (Too

Bizarre to Believe), yet there may be some truth in the rumours.

48. Halley, Britain’s premier Antarctic station, is named after

the British astronomer Sir Edmund Halley, who extraordinarily

was the first person to state that the Earth is hollow,

consisting of four concentric spheres. Another Antarctic enigma?

49. The experiments involved freezing the victim until

unconscious, then rapidly plunging the victim into hot water.

Other experiments, heinous in their morality and beneficial to

the Nazi cause, meant that all the results and documentation

detailing the experiments were amongst the information most

sought by the Allies. It is well known that without Nazi human

experiments, the United States would not have gone to the Moon

in 1969.

50. "The Final Surrender: For Lt Onoda, the shooting stops 29

years late", Daily Mirror, UK, 11 March 1974. Lt Onoda killed 39

people between the end of the war and his capture in 1974.

51. In June 1945, a Werewolf bomb exploded in Bremen Police

Headquarters, killing five Americans and 39 Germans. The

Werewolves were created by Himmler in 1944 and went on to fight

against the occupying forces until at least late 1947.

52. "Operation Highjump", typed into Google, produces 46,700

results, far exceeding any other Antarctic mission mentions by

thousands!

|

the British to set up

bases in many parts of Antarctica during the war in response to the

threat. And whilst the officially recorded British expeditions

mainly concentrated around the Antarctic Peninsula, those not

recorded were those that concentrated on investigating Queen Maud

Land—so named by Norwegian whalers prior to 1939 in honour of Queen

Maud of Norway (1869–1938), consort of King Haakon VII and formerly

Princess Maud of the United Kingdom, a granddaughter of Queen

Victoria.

the British to set up

bases in many parts of Antarctica during the war in response to the

threat. And whilst the officially recorded British expeditions

mainly concentrated around the Antarctic Peninsula, those not

recorded were those that concentrated on investigating Queen Maud

Land—so named by Norwegian whalers prior to 1939 in honour of Queen

Maud of Norway (1869–1938), consort of King Haakon VII and formerly

Princess Maud of the United Kingdom, a granddaughter of Queen

Victoria.