|

by Diego Cuoghi

Edited by Daniel Loxton

Translation by Daniela Cisi and

Leonardo Serni

The Skeptic Magazine

July 2004

from

Sprezzatura Website

|

“Meanwhile

the average man had become progressively less able to

recognize the subjects or understand the meaning of the

works of art of the past. Fewer people had read the

classics of Greek and Roman literature, and relatively

few people read the Bible with the same diligence that

their parents had done. It comes as a shock to an

elderly man to find how many biblical references have

become completely incomprehensible to the present

generation.”

—Kenneth Clark

introduction to Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in

Art by James Hall |

Around the world, millions of people believe that alien spacecraft

routinely visit our planet.1 This belief has been fueled

by 60 years of reported UFO sightings and thousands of anecdotal

claims. A growing number of print2 and web3

sources argue that there is solid documentary proof that UFOs have

been visiting us for hundreds of years, painted into the skies of

the European art of centuries past.

While it’s true that some pretty strange things appear in the

backgrounds of old paintings, they only look odd to modern

viewers.

A working knowledge of the complex artistic and symbolic conventions

used by Classical, Medieval, or Renaissance painters reveals that

these strange details meant something quite different to the artists

who painted them, and the audience they painted for. viewers.

A working knowledge of the complex artistic and symbolic conventions

used by Classical, Medieval, or Renaissance painters reveals that

these strange details meant something quite different to the artists

who painted them, and the audience they painted for.

A painting’s place in history influences

how objects in it are depicted, and that contextual information is

necessary to correctly identify those objects. Regrettably, the

authors who have discovered alleged UFOs in old paintings have

little knowledge of the meaning or context of the items which they

have selected as candidates for alien spacecraft.

Strangely enough, one of the motives for seeking UFOs in old

paintings was a particular observation about which skeptics and UFO

enthusiasts partially agreed. Skeptics have long found it suspicious

that thousands of UFOs apparently started arriving only after the

advent of science fiction.

This is hardly the most devastating or scientific criticism of

belief in UFOs, but it certainly makes a valid point: once people

started to write about fictional alien spacecraft, people suddenly

began to see them.

Some UFOlogists also felt uneasy about this coincidence. If the

“alien spaceship” hypothesis is correct, surely there would have

been UFOs in our skies before science fiction writers started

imagining aliens; and, if they’ve been visiting us for centuries,

historical records of extraterrestrial spacecraft should exist.

After all, people have been watching the skies for a very long time.

So, where’s the evidence of pre-Sci-Fi visitations? Where are the

accounts of saucers seen by medieval peasants, or of vast silvery

disks hovering over Roman garrisons? The truth is, there are no

historical records of anything matching the descriptions of modern

UFOs.4 This has prompt-ed many UFOlogists to comb through

ancient sources for obscure or hidden signs of premodern UFOs.

Perhaps, they reason, ancient observers, lacking the conceptual

framework provided by modern science (and science fiction) actually

did record spacecraft sightings—but without understanding what they

were seeing.

As Skeptic readers know, there is now a decades-long tradition of

pseudo-historical research devoted to uncovering cryptic signs of

alien “ancient astronauts” in the records, monuments, and artwork of

ancient cultures (Egyptian, Aztec, and so on). Since the 1970s, many

have been convinced (by writers such as Andrew Tomas or Erich von Däniken) that ancient, lost, or non-European cultures did record

prehistoric contact with aliens. If, as these “paleo-astronautic”

theorists imagine, aliens have visited here for millennia, and if

they were recorded by ancient non-European cultures, isn’t it

reasonable to hypothesize that similar evidence of their presence

should also be contained in the art of European societies as well?

Although the idea is reasonable enough, the conclusions they have

drawn so far have been seriously flawed.

The Art

A virtual cottage industry has emerged on the Internet to showcase

and discuss the many UFOs that have been “discovered” in the works

of long-dead painters. In one sense, the authors of these sites are

correct: if you search the back-grounds of enough old paintings

saucer-like objects can be found. Some examples are extremely

convincing, even to a skeptical eye.

A quick comparison of UFO websites reveals that the images offered

are generally the same ones. Once a new image appears on one site,

the others immediately pick it up, usually with the commentary that

goes along with it.

For web surfers with even a little knowledge of art history, the

first impression of these sites is that a very simplistic

methodology was used to compile them. To all appearances, the

standard practice is simply this: pick up an art book, preferably

one dealing with work from the 17th-century or earlier (religious

art is favored because it is crowded with odd objects). Browse

through the book for any strange detail with a circular, ellipsoid

or saucer-like shape. That’s it. This sys-tem obviously makes it

quite easy to discover puzzling objects and declare them “alien” or

“unidentified” without bothering to consider what they might have

symbolized in the period in which they appear.

It’s clearly foolish to publish anything (even on the web) on

subjects one knows nothing about. These authors err not just because

they misinterpret the symbolism, but because they don’t even realize

that it’s symbolism they’re looking at. The visual vocabularies they

are puzzling over are centuries (or even millennia) old. Those

archaic iconographic vocabularies are no more familiar in the TV age

than is Homer’s Greek or Virgil’s Latin. We shouldn’t be too hard on

UFOlogists for their mistakes in this unfamiliar arena, perhaps, but

we should feel free to debunk their poorly founded claims.

Another misunderstanding of these web UFO searchers is presuming

that the social role of the artist back then was the same as it is

today. Authors frequently make the anachronistic assumption that the

artists who executed these expensive, commissioned paintings had the

power or license to add details as they chose. It’s a mistake to

think that religious painters of, say, the 15th-century, were free

to record events they had personally witnessed, or that they would

have been allowed to add any non-canonical or un-codified elements

whatsoever.

The idea that artists should freely express themselves in their work

is a completely modern one. In past times, the patrons who choose

the subject and supervised the execution of the art-work (in these

cases, religious institutions or powerful nobility) would never have

allowed artists to insert stray elements from outside of previously

established conventions—especially in the case of religious

subjects.

Artists were, in those times, skilled

workers who were paid to do things in the prescribed way, and only

that way; they could no more insert flying saucers into their

commissions than your lawyer can add jokes or personal commentary to

your will. Even for master painters, tinkering with the schematic

conventions of their times could have been dangerous. Personal

editorializing would have been a publicly scandalous affront to

their patrons (who frequently held the powers of life and death, in

addition to controlling the prosperity of artists).5

Examples

Oddly, a striking failure of this UFOlogical fishing trip is the

relatively small number of examples it has managed to net. At this

point, one may be forgiven for wondering whether these authors, in

the course of their investigations, ever actually entered a museum

or a church. If they had, they would have been astonished to

discover the staggering array of strange objects depicted in old

paintings, statues, and other works of art!

So, what exactly is it that these web sites are showcasing? What

does art history have to say about the discovery of UFOs in

centuries-old paintings? Here are four examples. I include a

critique of each one to illustrate the shortcomings of their

reasoning.

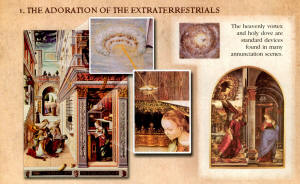

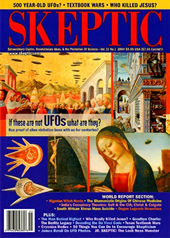

1.The Adoration of the Extraterrestrials

Carlo Crivelli,

Annunciazione (1486)

Anyone familiar with 15th-century religious painting will find

it absurd that the authors of some UFOlogy web sites are

astonished by the object in the sky of the Annunciation by

Carlo Crivelli (now at the National Gallery of London).

What they consider most surprising

is the fact that there is a ray of light coming down from this

“flying object” to touch the head of the Virgin Mary. This ray,

it is claimed, comes from a saucer-like UFO hovering among the

clouds. Unfortunately, casual web surfers will find that posted

reproductions of the key detail (the “saucer,” actually a circle

of clouds in the sky) are small, blurred, or pixilated to the

point of being indecipherable. (No one seems to have searched

for a better reproduction, and identical poor-quality versions

continue to spread from site to site).

On the Edicolaweb site,6 the commentary is quite

restrained:

“Painting by Carlo Crivelli,

known as The Annunciation, shown at the National Gallery of

London. In the sky hovers a large, bright circle, from which

a beam of light descends, reaching the crown worn by Mary.”

By contrast, a site called The UFOs

of Crivelli 7 gets right to the point:

“What most

attracts our attention is the peculiarity of the cloud shape:

indeed it appears to be quite solid, with a circular structure,

and clearly different from any other cloud surrounding it. It

may be either the sun circle (direct emanation of the divine

energy) or an object really seen and thus represented by Crivelli himself. As evidence of this latter hypothesis stands

the ‘thickness’ of the object, which is not an abstract entity:

in addition the resemblance of the ‘cloud’ to a UFO recently

seen in Veneto [a northern region of Italy] in January 1999 is

clear. The reader may judge for himself.”

Of course, the reader

can’t judge without a sharp detail of the cloud, but the blowup

provided is of even lower quality than is typical.

Had those publishing this claim bothered to become familiar with

the art of the period, they would know that there are a vast

number of Annunciations in which a ray reaches from a circular

cloud to the head of the Madonna. This scene is, like most

religious scenes, an established genre rendered in similar ways

many times by many people. These various Annunciations speak a

specialized iconographic language that modern viewers no longer

understand.

For example, the Crivelli painting represents divine power in a

very common way: an object in the sky, formed by a radiant

circle of clouds containing two circles of small angels. In

close-up, individual angels are clearly visible, peeking their

little heads and golden wings out over the clouds on which they

sit. This same cloud-with-rings-of-angels device is used in

Annunciations by Luca Signorelli, Pietro Alamanno, and others

(as well as in many Medieval and Renaissance paintings of

related subject matter) to depict the presence of God.

Sometimes this device is a small detail, an anchor at the divine

end of a thread that connects a holy person to God; at other

times it is the central image, a vast vortex of heavenly power.

If the beam emanating from the radiant cloud in Crivelli’s

painting were actually intended to represent the action of a

technological device—a Star Trek transporter, perhaps, or some

sort of laser communications system—it would seem extremely odd

that this advanced technology was employed, apparently, for the

purpose of beaming a bird onto the head of the Virgin. In the

context of Christian religious iconography the little white bird

is far less bizarre. In fact, painters routinely placed doves in

such beams of light, with these doves representing the Holy

Spirit and divine guidance descending to the blessed contactee.

2. The Shepherd’s Vision

The practice of representing the Holy Spirit as a dove is

familiar to Christians; indeed, it predates the word

“Christian.” For example, the oldest of the New Testament

Gospels, Mark, recounts that at his baptism, Jesus saw “the

heavens opened and the Spirit descending upon him like a dove.”

8 Today, American churches and chapels are commonly named

“Holy Dove,” and the tradition thrives worldwide in both visual

art and hymns.

In high-resolution reproductions,

the identity of Crivelli’s “UFO” is clear, but UFOlogy sites

typically offer only hazy, ambiguous, low-resolution smudges.

Crivelli no more saw a UFO with his own eyes than cartoonists

see clouds emerging from people’s heads when they are thinking;

in both cases, these artists simply utilized established

conventions for representing abstract or non-visual concepts.

The only mysteries here are why some UFOlogists are so quick to

leap to unwarranted conclusions, and so slow to provide their

readers with the information needed to honestly evaluate the

“evidence.”

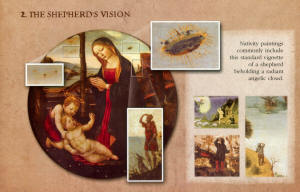

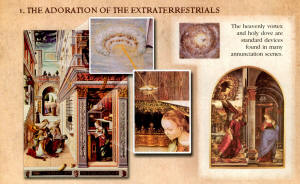

Madonna Col Bambino e San Giovannino (end of 15th century).

(Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John.) Attributed to

Sebastiano Mainardi or Jacopo del Sellaio. The Madonna and Child

with the Infant St. John, on display in the Sala d’Ercole in

Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, has been attributed to at least three

painters active in Florence at the end of the 1400s. For

convenience we’ll refer to this as a work by the general

favorite, Sebastiano Mainardi.9

This painting has excited UFOlogists more than any other. Many

see proof of a “close encounter” with a UFO in the upper-right

background behind the Madonna. In the depiction, a far-off

character shields his eyes while beholding an apparition in the

sky (his dog is equally interested).

Daniele Bedini writes in Notiziario UFO,10

“We

clearly see the presence of an airborne object, leaden in color

and inclined to port, sporting a ‘dome’ or ‘turret,’ apparently

identifiable as an oval-shaped moving flying device.”

Once again, with a few keystrokes, a radiant cloud painted half

a millennium ago has become a flying saucer. But this odd cloud

is not the only peculiarity of the painting: to the upper left,

we see the Nativity Star with three other small stars (or

perhaps flames) below it. These particulars—three clustered

stars, a luminous cloud—tell us that this painting follows an

ancient iconography, an austere and rigid way for interpreting

not only sacred subjects but also city life itself.

When this work was created, Florence was under the theocratic

sway of the infamous Fra’ (‘Brother’) Girolamo Savonarola. This

passionate fire-and-brimstone monk had gained great popular

influence with his powerful, persuasive sermons linking the

corruption he saw in the ruling Florentine Medici family with

the coming judgment fore-told in the Book of Revelation. Like

many people through-out history, Savonarola believed that greed,

decadence, and immorality were destroying his society (and his

church), and he called forcefully for a return to traditional

Catholic values.

When, under the pressure of an

advancing French invasion the Medici family was eventually

driven out, Florence declared itself a Republic—with Christ

himself as titular king. Although Savonarola had no official

political power in this new Republic, his opinions were the

authoritative foundation for a Florence reinvented with both

civil law and social norms based on Christian ideology. The

resulting theocratic state featured pervasive surveillance of

the people and control over their everyday lives (one could draw

parallels with the modern fundamentalists of Ayatollah

Khomeini’s Islamic Republic of Iran).

Under the grip of both popular religious fervor and a theocratic

regime, Florentines, while pursuing their cultural revolution,

invented a famous expression that still resonates today: the

so-called “bonfires of the vanities.” In these huge street

fires, symbols of the degenerate corruption associated with the

old Florence were gathered and publicly burned. Gambling

paraphernalia (like cards and dice) were fed to the flames along

with symbols of material greed (wigs and fineries, together with

trinkets and baubles), and symbols of moral decadence—‘obscene’

books, art, and precious objects.

Savonarola fell from grace within a few years, having angered

both the Vatican and the people of Florence. Ultimately he was

captured by a mob, arrested, tried, tortured, hanged, and then

burned for good measure. Soon, after ascending to the Papal

throne in Rome, the Medici family returned to power in Florence

as well.

During the Savonarola years, the dangerous cultural atmosphere

of suspicion and condemnation born from his preaching greatly

influenced the work of artists. Several, including Sandro

Botticelli (whose patrons had been the Medici family), soon

denounced their own earlier work as heathen, and proclaimed

themselves ready to represent mystical subjects in a “purer”

(but also more rigid, archaic and didactic) style. Others, like

Florentine sculptor Michelangelo (another Medici-affiliated

artist), simply fled the city.

Rejecting the “degenerate” artistic practices that had emerged

from the humanism and Neo-Platonism popular among the Medici

circles, Mainardi’s Madonna reflected the reactionary trend to

return to older, safer iconographic con-ventions.11

For example, three stars often appear in the paintings of the

previous century, and in far earlier Byzantine icons of the

Madonna. Often, these stars are painted on her veil, on her

shoulders, or on her forehead. Sometimes three rays stand in for

the stars, but by any variant they represent the “threefold

virginity” of the Madonna (i.e. before, during, and after the

virgin birth).

Despite extraterrestrial speculations, Mainardi’s “UFO” is

actually an element found in a great many Nativities of the 1400

and 1500s: the announcement to the shepherds, as told in the

Gospel of St. Luke:

“And an angel of the Lord

appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around

about them: and they were filled with fear. And the angel

said to them, ‘Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you good

news of a great joy.’”12

Elements of Mainardi’s Madonna are

found in many other paintings of the Nativity or the Adoration

of the Child (by artists such as Foppa, Pinturicchio, Aspertini,

Di Credi, Bronzino, Luini, Ghirlandaio, Van Der Goes, and so

on). Each of these includes the same angelic visitation scene

—either a luminous cloud, or an angelic figure, or an angelic

figure emerging from a luminous cloud. In almost all versions, a

lone shepherd holds a hand to his forehead, as if shielding his

eyes from the shining “glory of the Lord” described by Luke.

Often, the shepherd’s dog also marvels at the apparition.

It’s clear that Mainardi’s “UFO sighting” scene can be

confidently identified as the then-standard announcement scene.

But one might wonder, since there is no specific mention of

“luminous clouds” in Luke, where did this particular convention

come from?

Renaissance sacred art took scenes not only from the four

canonical Gospels, but also from apocryphal sources and

contemporary devotional texts containing popular characters. We

owe Giotto’s Mary’s Presentation to the Temple (or The Virgin’s

Wedding), the encounter between Jesus as a child and St. John

the Baptist by Leonardo, and other favorites to sources

extraneous to the canonical Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke or

John. Painters (and their employers, who chose the subjects)

also routinely mixed scenes and situations from heterogeneous

texts.

One of the apocryphal gospels most heavily drawn on by artists

of this period was James’ Protogospel, which features a

description of the Nativity in which no angels appear. Instead,

a cloud of light attends the birth:

“…and behold! a luminous

cloud over-shadowed the cave. And the mid-wife said: ‘My soul

has been magnified this day, because mine eyes have seen

wondrous things: that salvation has been brought forth to

Israel.’ And immediately the cloud disappeared out of the cave,

and such a great light shone in the cave that the eyes could not

bear it.”13

While Luke merely notes, “and the glory of the Lord shone round

about them,” the author of James’ Protogospel adds that, “the

eyes could not bear it.” And behold! Most paintings illustrate

the announcement scene with the shepherd shielding his eyes. In

the case of Mainardi’s Madonna, the angel is depicted as in this

apocryphal Gospel: a luminous cloud. This was hardly an

innovation.

Discussing angel iconography, Marco Bussagli’s History of

Angels14 quotes the 5th-century mystic Pseudo-Dionysus: “The

Holy Scriptures represent [angels] in the form of clouds to

indicate that the holy entities are filled with a hidden light

in an above-mundane way.” In the catalogue of Wings of God,

Bussagli writes, “All things considered, the Middle Ages turned

out to be a central period for the development of the Angelic

iconography, whose solutions were to be re-interpreted in a

markedly naturalistic way by the later cultures of the

Renaissance and the Baroque. Such is the case of the ‘Cloud

Angels’ that would be later propounded as winged figures over

soft cushions of vapor.”15

We can, then, firmly link Mainardi’s Madonna to political events

and iconographic traditions reigning at the end of the 1400s in

Florence, but not to alien spacecraft. The three smaller stars

under the great Nativity Star are symbols of the triple

virginity of Mary (before, during and after childbirth); the

shepherd with his hand on his forehead is a standard detail

found in dozens of Nativity or Adoration paintings of the same

age; and the luminous cloud, symbolic of God’s glory expressed

through his angelic agents, comes from the narration of the

nativity in the Protogospel of James.

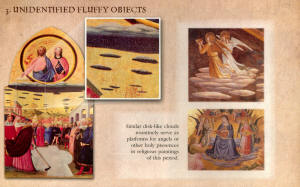

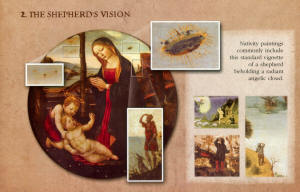

3. Unidentified Fluffy Objects

Il Miracolo Della Neve (c.

1428). Masolino da Panicale. (Napoli, Museo Nazionale di

Capodimonte.)

Promoted in the Italian press since

the early 1970s, this is one of the most commonly cited

“UFOlogic paintings.”16

Illustrating a 13th-century legend

regarding an alleged 4th-century supernatural event, Masolino da

Panicale (a.k.a. Tommaso di Cristoforo Fini) painted The Miracle

of the Snow as the central panel for an altarpiece triptych for

the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome around 1428. A web

author summarizes the legend:

According to historical

tradition, Pope Liberius was ordered by Angels to construct

a new church in the exact place where miraculous snowing

would soon be manifested. The day after, a strange substance

similar to snow fell from the sky in one warm day of August.

The phenomenon was limited to the single zone of Rome in

which was then constructed the basilica of Santa Maria

Maggiore…. What was the cause of this impossible snowing?

Masolino from Panicale, in his

painting, represents a detailed scene of the event, with snow

falling from a ‘large and lengthened cloud,’ grayish and with

the shape of a cigar. Under this cloud are many other smaller

clouds. Careful examination of these reveals that they do not

seem like normal clouds. They are, in fact, all clearly

delineated in their contours and not vaporous, and are

represented in identical pairs with only the upper portion

illuminated, as are many ‘flying saucers.17

Although this modern UFOlogical retelling refers to a “strange

substance similar to snow,” the original legend speaks of

literal snow falling on Rome miraculously in August of the year

352 CE. According to the legend, apparently first told by Fra

Bartolomeo from Trento in the first half of 13th-century in the

Liber Epilogorum in Gesta Sanctorum,

…in the morning…the inhabitants

of the Esquiline hill got a strange surprise: during the

night snow had fallen, and a soft mantle of it covered the

soil. With such a miracle the Virgin Mary indicated to a

noble called Giovanni and his wife that she wanted a shrine

built there in her honor.

For a long time the old couple,

who had no sons, had desired to employ their riches in a

work that honored the Mother of God and, to such an aim,

prayed with fervor so great that she showed them the way in

which they could fulfill their wish. The Virgin appeared to

them in a dream, telling them to build a church dedicated to

Mary in the place where the following morning would reveal

that snow had fall-en miraculously during the night.

Astonished by the miracle, the

couple went to Pope Liberius, to tell him what happened; but

the pope had, during the night, dreamed the same thing!

Liberius, followed by Giovanni and a crowd, went up the

Esquiline hill and found that the still intact snow marked

the outline of the new church—which was soon constructed at

the expense of Giovanni and his wife.18

Historically, things seem to have

happened differently. The foundation of the basilica of Santa

Maria Maggiore on the Esquiline hill was actually laid during

the reign of Pope Sixtus III in the middle of the 5th-century.

It was the first church dedicated to the Virgin Mary (officially

defined as the “Mother of God” in Ephesus in 431 CE by the Third

Ecumenical Council). Esquiline may have been chosen in order to

eliminate the old pagan cult of Juno Lucina19 (a Roman goddess

associated with light and childbirth), which had a temple on the

same hill.

Because the Miracle of the Snow captured the popular

imagination, many artists represented the scene (and various

churches dedicated to the Madonna of the Snow were constructed

else-where in Italy). In Florence we find the miracle

represented in a fresco in the church of Santa Felicita, and in

a 14th-century stained-glass win-dow in the palace of

Orsanmichele.

As far as we know, the story was first narrated a millennium

after the legendary event. Another century passed before

Masolino painted the miracle scene with those strange

“UFO-clouds.” But how unusual really are those clouds in the

context of 15th-century art? Not unusual at all, it turns out,

because Masolino painted similar clouds in other projects,

including a Madonna with Child. Other painters of the time,

including Benozzo Gozzoli, also represented clouds in the same

stylized way.

Obviously, these clouds are schematically stylized, and aspire

to less realism than earlier sacred art from the first half of

15th-century; equally obviously, they are still clouds. Here,

realism is set aside in favor of simplicity, but most audiences

have no trouble identifying the cloud elements correctly.

Admittedly, these clouds do somewhat resemble modern flying

saucer images, but this was no more the intent of Masolino than

of his contemporaries who used the same convention.

The major cloud element aids our

identification of the object as a cloud, if any aid is needed,

with its billowy, frankly cloud-like upper surface. And, the

simplified (but nonetheless obvious) amorphous asymmetry of the

other clouds confirms that these are not meant by the painter to

be similar technological artifacts. It may be worth pointing out

that we have no reason whatsoever to suspect that Masolino ever

personally saw a flying saucer, a giant Jesus gesturing from a

gargantuan medal-lion in the sky, or, for that matter, a sky

made from gold leaf.

The snow legend itself could, conceivably, have been a

oral-historical record of a real atmospheric occurrence.

Independent accounts indicate that while snow in Rome during

August would certainly have been extraordinary, it could

actually have happened. Exceptional atmospheric events of this

kind have been recorded more recently. For example, in June of

1491 snow piled up to a foot high in Bologna. Three days later,

snow covered Ferrara as well. Snow is documented to have fallen

on the coasts of the Calabria in May of 1755, and in Lunigiana

in July of 1756. Prato is a fine modern example of a city

whitened in August: in 2000 it became covered in hail (in

certain points, almost 30cm deep).

It’s not impossible, therefore, that such an extraordinary event

could have occurred. Distant memories, passed along orally for

centuries, picking up rich legendary details could have

eventually transformed into the “Miracle of the Snow.”

Whether the legend is “true” in this sense is beside the point.

For our purposes, it is sufficient to conclude that Masolino

illustrated a then-current legendary narrative, according to

main-stream conventions of his time, at a church whose

miraculous foundation was the subject of that very tale. There

is no reason to speculate that he personally witnessed an alien

invasion, and no way that he could have witnessed the original

“miraculous” event (if it ever occurred); further, there’s no

hint anywhere that the original legend recorded either alien

contact or the sighting of UFOs.

|

The Images That

Started It All

In 1964, the “discovered” by art student Alexandar

Paunovitch in a 16th-century fresco of the

crucifixion of Christ, located on the wall of the

Visoki Decani Monastery in Kosovo, Yugoslavia. The

French magazine Spoutnik printed them, and they have

been featured in many books and web pages ever since

as “spaceships with a crew.”

While

a layperson might be completely mystified by these

suggestive images, a Medieval art historian would

only need to know that they were located in the

upper corners of a depiction of Christ’s crucifixion

to identify them. While

a layperson might be completely mystified by these

suggestive images, a Medieval art historian would

only need to know that they were located in the

upper corners of a depiction of Christ’s crucifixion

to identify them.

Many crucifixion paintings and mosaics done in the

Byzantine style show the same odd “objects” on

either side of the cross. They are the Sun and the

Moon, often represented with a human face or

figure,

a common iconographic tradition in the art of the

Middle Ages. figure,

a common iconographic tradition in the art of the

Middle Ages.

James Hall, author of the Dictionary of Subjects &

Symbols In Art writes: “The sun and moon, one on

each side of the cross, are a regular feature of

Medieval crucifixion [paintings]. They survived into

the early Renaissance but are seldom seen after the

15th century. Their origin is very ancient. It was

the custom to represent the Sun and Moon in images

of the pagan sun gods of Persia and Greece, a

practice that was carried over into Roman times on

coins depicting the emperors.

…[T]he sun is [sometimes represented as] simply a

man’s bust with a radiant halo, the moon [as] a

woman’s, with the crescent of Diana. Later they are

reduced to two plain disks. The moon having a

crescent within the circle, may be borne by angels.

The sun appears on Christ’s right, the moon on his

left.”

The Sun and Moon are depicted as anything from a

flat disk to a hollow comet-tailed ball. The figures

within vary from a simple face to elaborate

depictions of Apollo and Diana in their chariots

driving horses or oxen. The Sun and Moon are also

featured on crucifixions painted by Dürer, Crivelli,

Raphael, and Bramantino. |

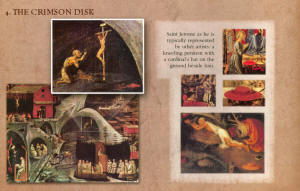

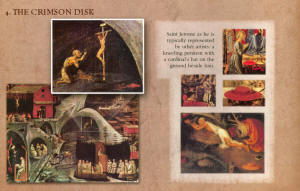

4.The Crimson Disk

Other examples abound, and many of them are decidedly weird. Of

these, the most amusing might easily be the “UFO” identified in

Paolo Uccello’s Scene di Vita Eremitica (Scenes of Monastic

Life), circa 1460-1465.20 That UFO is, no doubt, a large red

hat.

The painting is a montage of various key scenes of monastic

life: at the bottom left, the Virgin appears to St. Bernard;

above, a group of monks flagellate themselves in front of the

Crucifix; at the bottom right, a saint (probably St. Romuald)

preaches; while at the top, St. Francis kneels down and receives

the Stigmata. In the middle, in a large cave, St. Jerome prays

before the crucified Christ. Beside him is his hat.

According to one author on a UFOlogy

site, this,

“is a saucer object, suspended in the air and

surmounted by a red domed top. Red in color, the object comes

out over the dark background by contrast. The dynamic movement

of the flying object is rendered by means of light brush

strokes, again red in color, which provide the effect of a

sudden turn.”21

But the object is plausible as a saucer only if our view is

restricted to a small section of the painting. Viewing the

entire painting makes clear that the “saucer object” is located

inside the cave, on the ground beneath the crucifix, beside the

kneeling St. Jerome. It is also clearly quite small.

At this point, most Catholics, and many people with even minimal

knowledge of art history should easily recognize this red object

as a traditional Catholic cardinal’s hat— red, rounded,

broad-brimmed, and trailing tasseled cords.

According to tradition, St. Jerome became an eremite (a hermitic

monk) after renouncing his ecclesiastic career. By the time of

Uccello, Jerome was a standard subject of religious art, and

standard ways of presenting him had evolved.

“According to one

of the most common iconographical modules, Jerome in the desert

flagellates his chest with a stone while kneeling down in front

of a Crucifix.”22

In this iconographic scheme (one of three or

so main types for this saint), Jerome “is represented as an

elderly man with white hair and beard, his cardinal hat close to

him…As a penitent, dressed with skins or poor garments.”23

The small animal Uccello places with the saint is actually a

lion. According to an archetypical legend, Jerome saved and then

tamed a wild lion by extracting a thorn from its paw.24

Despite widespread association of a tamed lion with St. Jerome

in art and tradition, many web sites promoting UFOs continue to

quote an article by Umberto Telarico25 in which the

animal is described as a “little dog.”

A biography of St. Jerome from around 1348,

“gave artists the

following instructions, which became canonical, about the

saint’s iconography: ‘Cum capello, quo nun cardinals utuntur,

deposito, et leone mansueto’ [‘with a hat, the kind used by

cardinals, not worn but set aside, and the tamed lion’].”

The

hat at issue is the cardinal’s hat present in so many

representations of Saint Jerome, together with the lion. The

fact that the saint was never a cardinal, and never met a

wounded lion does not matter. Once representations of Jerome

acquired these arbitrary characteristics, they became part of

the “facts” to be conveyed to posterity—fortunately by means of

wonderful masterpieces.26

Other artists freely employed these guidelines before and after

Uccello. In less panoramic paintings, the tradition-al hat

element was generally illustrated at a size sufficient to

prevent its misinterpretation as a UFO. In the Scenes of

Monastic Life, however, it is merely a small identification code

for the saint. Although it fails to identify Jerome for modern

UFOlogists, Uccello would have assumed his 15th-century audience

to be as casually familiar with this vocabulary as we might be

with such cultural icons as Lincoln’s beard, “The Force,” or the

phrase “D’oh!”

Conclusion

There are important topics on which skeptical empiricists and

Christians of various denominations are sometimes divided: did

such-and-such a miracle occur as a literal historical event? Is

there a place for biblical creationism in public schools? What are

the demarcation lines between issues of faith and issues of

falsifiable fact?

On the issue of UFOlogical hijacking of Christian artistic

masterpieces, however, they have solid common ground. It’s clear

that projecting modern concepts of alien visitation onto ancient

European canvasses is unwarranted. The examples offered by web and

book authors to date have sometimes been superficially striking, but

all have proven completely vacuous upon even moderately close

examination.

From either a Christian or an art historical perspective, seeing

UFOs in ancient paintings represents a distortion of both the true

meaning of that art and the intention of its devout creators. Many

Christians are likely to find offensive (or at least bemusing)

unfounded suggestions that some of history’s greatest artistic

expressions of the Christian faith, in fact, instead record

alien visitation. The willfully ignorant confusion of depictions of

the Virgin Mary, the Holy Spirit, or other religious symbolism for

aliens themselves is even less likely to sit well with believers.27

Why do some people believe UFOs are represented in these paintings?

The passage of time is partly to blame. Perhaps UFOlogists cannot be

faulted for incorrectly translating the visual languages of

centuries past. Time trans-forms languages, a fact all high school

English students realize when they find they need to translate

archaic words and expressions in order to understand Shakespeare.

There is even a core of commendable curiosity, an undisciplined sort

of scientific inquiry, behind some of these projects.

Despite this, however, it is fair to conclude that UFOlogists have

been far too quick to draw conclusions from their misunderstandings

of odd details in old paintings. Their failure to seek alternative

explanations for UFO-like objects has led them to exhibit sloppy

thinking, to diminish great works of historical piety, and to be

distracted from more promising candidates (if there are any) when

seeking proof of alien visitation.

References

-

Although belief in alien visitation

fluctuates, about 1/3 of American adults agree that some UFOs

contain extraterrestrial beings. Using the 2001 figures from the

National Science Foundation Surveys of Public Understanding of

Science and Technology, in which 29% of American adults agreed

that UFOs represent an alien presence, and assuming that the

U.S. has a population of about 293 million people, we can

estimate that 85 million Americans believe—a number more than

four times greater than the total population of Australia. While

29% of Americans believe in UFOs, incidentally, according to

other polling data “just 9% know what a molecule is.” For more

on U.S. belief in the paranormal see Susan Carol Losh et al,

“What Does Education Really Do? Educational Dimensions and

Pseudoscience Support in the American General Public,

1979-2001.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 27, No. 5,

September/October 2003. Amherst, NY. For thoughts on science

illiteracy, see the source for the above quote about molecules:

Norman Augustine, “What We Don’t Know Does Hurt Us. How

Scientific Illiteracy Hobbles Society.” Science, Vol. 279, No.

5357, Issue of 13 Mar 1998, pp.1640-1641.

-

See, for example, S. Boncompagni,

Clypeus #29, 1970; D. Bedini, Notiziario UFO #81, 1979; and,

Mass, the Newspaper of the Mysteries #107, 1980. (All Italian

language sources.)

-

Here are a few typical examples,

with Italian language sites in italics. Where quotes from these

or other Italian sources are used elsewhere in this article,

they have been translated, edited for English comprehension, and

corrected for typesetting.

-

There are, however, enough

similarities between some abduction accounts and certain forms

of ‘demonic’ harassment as subjective, experiential events to

merit investigation into the possibility that similar brain

activities are responsible for some subset of both. Victims of

‘aliens’ and ‘demons’ clearly describe different sorts of

creatures (effectively ruling out the possibility that both

sorts of event were caused by the same, objectively existing

alien species), but often describe similar symptoms of

paralysis, a weight on their chest, and so on. See, for example,

Andrew D. Reisner, “A Psychological Case Study of ‘Demon’ and

‘Alien’ Visitation,” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 25, No. 2,

March/April 2001, Amherst, NY.

-

An amusing expression of the power

of an aristocratic patron took place in Florence in 1494. Piero

de’ Medici, inspired by a heavy snowfall, called for the

sculptor Michelangelo to come at once and execute a commission.

This commission was a snowman. Michelangelo, of course, did what

he was told. (Nathaniel Harris, 1981. The Art of Michelangelo,

Optimum Books, Twickenham, England, 1987.)

-

http://www.edicolaweb.net/ufo_a04g.htm

(English translation by Diego Cuoghi; translated text edited for

English comprehension by Daniel Loxton.)

-

http//digilander.libero.it/mysterica/Ufocrivelli.htm

(English translation by Diego Cuoghi; translated text edited for

English comprehension by Daniel Loxton.)

-

Mark 1:10 (Revised Standard

Version). Matthew 3:16 also describes the Spirit in this scene

as “descending like a dove, and alighting on” Jesus. Luke 3:21

is still more literal, insisting that the “Holy Spirit descended

upon him in bodily form, as a dove.” Finally, John 1:32 tells us

that the Baptist “saw the Spirit descend as a dove…”

-

The Museum tag identifies the artist

as “Jacopo del Sellaio,” but the catalog entry under No.

00292620 asserts that the painting is best attributed to

Sebastiano Mainardi (1450-1513), member of the clique of

Ghirlandaio that worked in Florence at the end of the 1400s, but

also notes that elements of this painting (especially in the

figure of the Madonna) bear remarkable resemblances to elements

of works by Lorenzo di Credi.

-

Daniele Bedini, Notiziario UFO #7

(Jul-Aug 1996).

-

The archaic detail of the three

stars symbolizing the threefold virginity of Mary, and the

rendering of the Angel not as an anthropomorphic character, but

as a “cloud of light,” all suggest that the painter was

(willingly or unwillingly) following the teachings of Girolamo

Savonarola, the Dominican monk who preached a return to

tradition and purity in the arts as well as in city life. The

catalogue entry of the Palazzo Vecchio Museum for this painting

notes that it shares “striking similarities” with the works of

Lorenzo di Credi. And it may be worthy of note that Lorenzo di

Credi was one of the most devout among the followers of

Savonarola, attending the burning of every nude he ever drew,

before finally becoming a monk himself.

-

Luke 2:10, Revised Standard Version.

-

Apocryphal Gospels edited by

Marcello Craveri, Torino, 1969, p. 21. Italian edition.

-

Marco Bussagli, History of Angels.

Rusconi, 1991.

-

Marco Bussagli, catalogue Wings of

God.

-

See, for example, S. Boncompagni,

Clypeus #29, 1970; D. Bedini, Notiziario UFO #81, 1979; and,

Mass, the Newspaper of the Mysteries #107, 1980.

-

R. Pinotti,

http//www.notizieufo.com

-

Andrea Lonardo. 2000. The Jubileum

Places in Rome. San Paolo Publishing. (Automatic translation by

Altavista-Babelfish; translated text edited for English

comprehension by Daniel Loxton.)

-

Juno was the Roman counterpart to

the Greek goddess Hera. Her husband was Jupiter, the Roman

version of the supreme Greek god Zeus.

-

Scenes of Monastic Life (Scene di

Vita Eremitica), also known as La Tebaide. (Now at the Gallerie

Dell’Accademia, Firenze.)

-

http://www.edicolaweb.net/edic042a.htm

(English translation by Diego Cuoghi; trans-lated text edited

for English comprehension by Daniel Loxton.)

-

http//www.cini.it/palazzocini/testi/ferrar/gero.html

(English translation by Diego Cuoghi; translated text edited for

English comprehension by Daniel Loxton.) No longer posted.

-

http://www.thanatos.it/cultura/personaggi/san_girolamo.htm

(English translation by Diego Cuoghi; translated text edited for

English comprehension by Daniel Loxton.) No longer posted.

-

The lion is also the symbol of

evangelist St. Mark (patron saint of Venice), and thus of the

Republic of Venice. St. Jerome was said to have been born in

Dalmatia, a territory of Venice. Uccello himself had important

Venetian patrons.

-

Notiziario UFO #8 (1996).

-

From an article in FMR (the art

magazine edited by Franco Maria Ricci), by Erminio Caprotti.

Here, Caprotti quotes Andrea from Bologna about the iconography

of Saint Jerome. FMR #94, September 1992. (English translation

by Diego Cuoghi; translated text edited for English

comprehension by Daniel Loxton.)

-

Many UFOlogical speculations about

these paintings actually go deeper than those dealt with in this

article: some believe that the Bible itself records either a few

encounters with aliens or a vast history of such contacts. From

this perspective, presumably, biblical miracles would be

technological actions, visible heavenly phenomena would be

spacecraft in flight, and prophetic or messianic messages would

come from other literal extra-solar worlds. Websites flirting

with these arguments have an unlikely, unfalsifiable, and more

or less bulletproof answer to skeptics who point out that these

paintings were meant to depict miraculous biblical events: they

simply claim that those events really were spacecraft sightings

by the biblical authors, and that later artworks of these scenes

are therefore UFO paintings after all.

|

viewers.

A working knowledge of the complex artistic and symbolic conventions

used by Classical, Medieval, or Renaissance painters reveals that

these strange details meant something quite different to the artists

who painted them, and the audience they painted for.

viewers.

A working knowledge of the complex artistic and symbolic conventions

used by Classical, Medieval, or Renaissance painters reveals that

these strange details meant something quite different to the artists

who painted them, and the audience they painted for.