|

by

Jon Christian Ryter

April 19, 2005

from

JonChistianRyter Website

Only two days and four ballots into the

election process to select a new pontiff for the Roman Catholic

Church, Germany’s Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger emerged as the

new pontiff, taking the name Pope Benedict XVI, and raising

the specter that he may have unwittingly—at and least partially—

fulfilled a prophecy uttered by St. Benedict (b.480-d.547AD)

that the last pope of Roman Catholic would be a

Benedictine. While Ratzinger was never an Olivetan

monk, there is a certain prophetic irony in the papal name he

chose. A second irony may come from St. Malachy’s prophecy

itself. In his prophecy, the 12th century cardinal

described the last pope by the symbol, Glory of the Olives.

While those speculating what the term means naturally connected

olives with the olive branch—which denotes peace—and

saw the last pope as a peacemaker who would likely help bring

peace to the Middle East. A peaceful solution to the

dilemma between the Palestinians and the Jews is a precursor to

Bible prophesies concerning the end-times. Perhaps the analogy is

even more simple: Only two days and four ballots into the

election process to select a new pontiff for the Roman Catholic

Church, Germany’s Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger emerged as the

new pontiff, taking the name Pope Benedict XVI, and raising

the specter that he may have unwittingly—at and least partially—

fulfilled a prophecy uttered by St. Benedict (b.480-d.547AD)

that the last pope of Roman Catholic would be a

Benedictine. While Ratzinger was never an Olivetan

monk, there is a certain prophetic irony in the papal name he

chose. A second irony may come from St. Malachy’s prophecy

itself. In his prophecy, the 12th century cardinal

described the last pope by the symbol, Glory of the Olives.

While those speculating what the term means naturally connected

olives with the olive branch—which denotes peace—and

saw the last pope as a peacemaker who would likely help bring

peace to the Middle East. A peaceful solution to the

dilemma between the Palestinians and the Jews is a precursor to

Bible prophesies concerning the end-times. Perhaps the analogy is

even more simple:

the Benedictines were

Olivetan monks, and its leader, rightfully, can be

construed as the glory of the olives.

Time will tell. And time is running out.

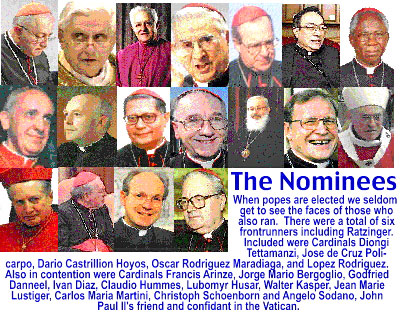

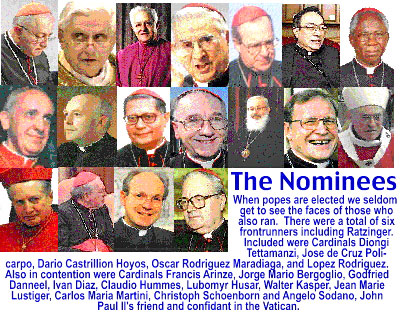

With respect to the conclave that met

and selected a new pontiff in what tied as the second fastest papal

election in this century, if popes were picked like ponies, the

bookmakers favoring John Paull II’s closest friend,

Cardinal Ratzinger of Germany would have crowned him with a

wreath of roses as they would the winner of racing’s Triple

Crown (image right... ) By the time of

Pope John Paul II’s funeral on April

8, Ratzinger had 50 of the 78 votes he needed to assure his victory

already in his pocket. With only 115 eligible voters (two eligible

cardinals, one from Mexico and one from the Philippines were sick

and did not come) Ratzinger, known as the Dean of the Cardinals,

still needed to pull 28 additional ballots out of his hat to win in

the opening rounds of voting where 2/3 of the cardinals had to agree

before the pontificating of a candidate could occur. It did not seem

likely, with the cultural differences of the cardinals and the

liberal or conservative personal agendas that each of them who

actively campaigned for the job carried with them into the Sistine

Chapel on April 18, that either of the two key front-runners would

win since it appeared more likely that gridlock would kill Ratzinger

and Italian Cardinal Dionigi Tettamanz’s chances of winning. When

Ratzinger failed to score a first or second ballot victory, the

oddsmakers raised him from the 4-to-1 favorite to a 7-to-1 maybe.

Many of the newly anointed bishops and cardinals also favored

Cardinal Angelo Sodano who greatly influenced the decisions of John

Paul II on "promotions" within the Catholic hierarchy. Sodano played

a key role in selecting all of the cardinals appointed from 2001

until the death of his benefactor and friend, John Paul II. Although

popular with the Italian laity, Sodano was clearly out of the

running before the running even began. He knew he would never get

the nod from the conclave because his influence died as the last

breath passed from the lips of John Paul II. The political cardinals

in the Vatican threw their support behind Ratzinger. Anyone who

believes that Cardinal Ratzinger’s elevation was God-ordained

through prayer and not politically-manipulated by a master

politician simply doesn’t understand the art of campaigning for

office.

The three most influential voting blocks in the conclave were the

Italians—with 20 votes, the United States—with 11 votes and the

Spanish-speaking nations, which collectively had 22 votes. There

were 17 votes each in North and South America, giving the western

hemisphere cardinals a bloc of 34 votes. Europe has enough votes to

elect a pope without the consensus of any other continent—58

votes—if ten days elapsed without naming a pope. Had that happened,

very likely a compromise candidate from one of the emerging

Spanish-speaking nations would have been selected.

But, in the final analysis, Cardinal Ratzinger, who had a

deliberate, well-calculated plan to win the job, won the job.

Reportedly Ratzinger was already campaigning for the job when the

Vatican announced that the death of John Paul II was imminent.

Ratzinger really wanted to be the pontiff (unlike his friend, Polish

Cardinal Karol Wojtkyla who not only did not campaign for the

job—but was surprised when he got it).

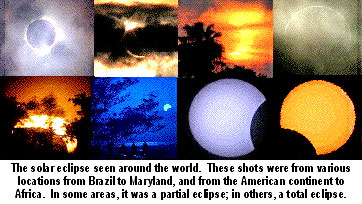

As the Conclave of Cardinals met on Monday, April 18, 2005 to select

the replacement for Pope John Paul II, few people in the world were

aware that the bizarre hybrid eclipse witnessed by millions of

people around the world on April 8, 2005 was prophesied by a

Catholic cardinal in 1140 AD specifically as a sign for that

pontiff. Pope John Paul II was described by 12th century Roman

Catholic Cardinal Malachy as "De Lobaore solis" (Of the eclipse of

the sun).

The Malachy Prophecy, penned by

Cardinal Malachy while on

his way to Rome for the coronation of Innocent II, described by

symbol, the papal succession from Celestine II (the pope would

succeed Innocent II) to the end of the world. Interestingly, on the

day of his birth, a solar eclipse occurred that was visible over

Poland—the nation of Karol Wojtkyla—the man who become pontiff of

the Roman Catholic Church.

By the time of John Paul II’s death, the Malachy Prophecy has

proven

to be 98% accurate. Whether or not it proves to be 100% accurate

will depend on whether or not any other pontiffs follow the pope who

was symbolically described as Gloria Olivae (the glory of the

olives)—and whether the events known as the Rapture and

the

Tribulation commence during the reign of Pope Benedict XVI.

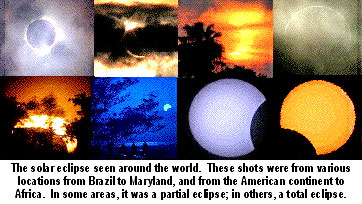

When the description of this uncommon hybrid type of eclipse

appeared in the article

The Malachy Prophecy scant

hours before the eclipse began to appear, the site received scores

of emails from readers poophahing the notion that an eclipse

alternating from a partial to a total eclipse would circumvent the

globe. While anular eclipses are a rare phenomenon, they are not

unknown. The April 8 hybrid eclipse was visible from within an

angular corridor that was predominantly visible from the southern

hemisphere. The total eclipse, which began southeast of New Zealand

traveling on a narrow band 28 kilometers wide quickly narrowed to a

sliver within the first 13 minutes of its journey past of Tahiti on

its way to Pitcairn Island. It continued on a northeastern course as

it crossed the Pacific Ocean to Panama, Columbia and Venezuela. (One

of the photos, above, was taken on

Pitcairn Island). The moon’s

penumbral shadow cast a wide swath across half of the planet,

covering all of New Zealand, Australia, the South Pacific islands

and much of South and North America from southern California on the

west coast to New Jersey on the east coast. Over a period of 3 hours

and 24 minutes, the eclipse traveled 14,200 kilometers. When the description of this uncommon hybrid type of eclipse

appeared in the article

The Malachy Prophecy scant

hours before the eclipse began to appear, the site received scores

of emails from readers poophahing the notion that an eclipse

alternating from a partial to a total eclipse would circumvent the

globe. While anular eclipses are a rare phenomenon, they are not

unknown. The April 8 hybrid eclipse was visible from within an

angular corridor that was predominantly visible from the southern

hemisphere. The total eclipse, which began southeast of New Zealand

traveling on a narrow band 28 kilometers wide quickly narrowed to a

sliver within the first 13 minutes of its journey past of Tahiti on

its way to Pitcairn Island. It continued on a northeastern course as

it crossed the Pacific Ocean to Panama, Columbia and Venezuela. (One

of the photos, above, was taken on

Pitcairn Island). The moon’s

penumbral shadow cast a wide swath across half of the planet,

covering all of New Zealand, Australia, the South Pacific islands

and much of South and North America from southern California on the

west coast to New Jersey on the east coast. Over a period of 3 hours

and 24 minutes, the eclipse traveled 14,200 kilometers.

The first recorded annular eclipse (a hybrid that switches from a

total to a partial eclipse and back again) occurred on May 6,

1464—30 years before Christopher Columbus set sail on a journey that

would bring him to the New World. The next hybrid eclipse will occur

on April 20, 2023.

|

Only two days and four ballots into the

election process to select a new pontiff for the Roman Catholic

Church, Germany’s Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger emerged as the

new pontiff, taking the name Pope Benedict XVI, and raising

the specter that he may have unwittingly—at and least partially—

fulfilled a prophecy uttered by St. Benedict (b.480-d.547AD)

that the last pope of Roman Catholic would be a

Benedictine. While Ratzinger was never an Olivetan

monk, there is a certain prophetic irony in the papal name he

chose. A second irony may come from St. Malachy’s prophecy

itself. In his prophecy, the 12th century cardinal

described the last pope by the symbol, Glory of the Olives.

While those speculating what the term means naturally connected

olives with the olive branch—which denotes peace—and

saw the last pope as a peacemaker who would likely help bring

peace to the Middle East. A peaceful solution to the

dilemma between the Palestinians and the Jews is a precursor to

Bible prophesies concerning the end-times. Perhaps the analogy is

even more simple:

Only two days and four ballots into the

election process to select a new pontiff for the Roman Catholic

Church, Germany’s Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger emerged as the

new pontiff, taking the name Pope Benedict XVI, and raising

the specter that he may have unwittingly—at and least partially—

fulfilled a prophecy uttered by St. Benedict (b.480-d.547AD)

that the last pope of Roman Catholic would be a

Benedictine. While Ratzinger was never an Olivetan

monk, there is a certain prophetic irony in the papal name he

chose. A second irony may come from St. Malachy’s prophecy

itself. In his prophecy, the 12th century cardinal

described the last pope by the symbol, Glory of the Olives.

While those speculating what the term means naturally connected

olives with the olive branch—which denotes peace—and

saw the last pope as a peacemaker who would likely help bring

peace to the Middle East. A peaceful solution to the

dilemma between the Palestinians and the Jews is a precursor to

Bible prophesies concerning the end-times. Perhaps the analogy is

even more simple:

When the description of this uncommon hybrid type of eclipse

appeared in the article

When the description of this uncommon hybrid type of eclipse

appeared in the article