|

Knights’ New Dawn

As HUMAN HISTORY entered the eighteenth century, changes were

occurring.

The Inquisition was almost dead and the Bubonic Plague was

dying with it.

Students of

Masonic history know that the early 1700’s were an

important period for Freemasonry. Masonic lodges in England had

attracted many members who were not masons or builders by trade. This

happened because Freemasonry was evolving into something other than

a trade guild. It was becoming a fraternal society with a secret

mystical tradition. Many lodges were quietly opening their doors to

non-masons, especially to local aristocrats and men of influence. By

the year 1700, an estimated70% of all Freemasons were people from

other occupations. They were called “Accepted Masons” because

they were accepted into the lodges even though they were not masons

by trade.

On June 24, 1717, representatives from four British lodges met at the

Goose and Gridiron Alehouse in London and created a new Grand Lodge.

The new Grand Lodge,

which was called by some “The Mother Grand Lodge of the World,”

officially dropped the guild aspect of Freemasonry (“operative

Freemasonry”) and replaced it with a type of Freemasonry that was

strictly mystical and fraternal (“speculative Freemasonry”). The

titles, tools and products of the mason’s trade were no longer

addressed as objects that members would use in their livelihoods.

Instead, the items were transformed entirely into mystical and

fraternal symbols. These changes were not made suddenly, but were

the result of a trend which had already begun well before 1717.

A number of histories incorrectly state that the Mother Grand Lodge

of 1717 was the beginning of Freemasonry itself. As we have seen,

Freemasonry’s roots were firmly established long before then, even

in England. For example, one Masonic legend relates that Prince Edwin

of England had invited guilds of Freemasons into his country as

early as 926 A.D. to assist the construction of several cathedrals

and stone buildings. Masonic manuscripts dating from 1390 and 1410

have been reported. Handwritten minutes from a Masonic meeting from

the year 1599 are reproduced in Albert Mackey’s History of

Freemasonry. Freemasonry was so well-established in England by the

16th century that a well-documented schism in 1567 is on record. The

schism divided English Freemasons into two major factions: the

“York” and “London” Masons.

The new Grand Lodge system established at the Goose and Gridiron

Alehouse in 1717 consisted at first of only one level (degree) of

initiation. Within five years of the Lodge’s founding, two

additional degrees were added so that the system consisted of three

steps: Entered Apprentice, Fellow Craft, and Master Mason. These

steps are commonly called the “Blue Degrees” because the color blue

is symbolically important in them. The three Blue Degrees have

remained the first three steps of nearly all Masonic systems ever

since.

The Mother Grand Lodge issued charters to men in England, Europe and

the British Empire authorizing them to establish lodges practicing

the Blue Degrees. The colorful fraternal activities of the lodges

provided a popular way for men to spend their time and Freemasonry

soon became quite

the rage. Many lodge meetings were held in taverns where robust

drinking was a featured attraction. Of course, many members were also

drawn into the lodges by promises of fraternity and spiritual

enlightenment.

The new Mother Grand Lodge was reportedly very strict in its rule

forbidding political controversy within the lodges. Ideally,

Freemasonry was to be independent of political issues and problems.

In practice, however, the Mother Grand Lodge, which was established

only three years after the coronation of the first Hanoverian king,

supported the new German monarchy at a time when many Englishmen

were

strongly opposed to it. One of the earliest and most influential

Grand Masters of the Mother Lodge system was the Rev. John T. Desaguliers, who was elected Grand Master in 1719.

Desaguliers had

earlier written a tract stating that the Hanoverians were the only

legitimate sovereigns of England under the “laws of nature.” On

November 5, 1737, he conferred the first two Masonic degrees

on Frederic, Prince of Wales—a Hanoverian. During the ensuing

generations, members of the Hanoverian royal family even became Grand

Masters.*

* Augustus Frederick (1773-1843), the ninth son of George III, was

Grand Master for the thirty years before his death. Prior to that,

his older brother, who became King George IV, had held the Grand

Master position. A later royal Grand Master was King Edward VII, son

of Queen Victoria; Edward served as Grand Master for 27 years while

he was the Prince of Wales. The most recent royal Grand Master to

become a king was the Duke of York, who afterwards became King

George VI (r. 1936-1952).

The English Grand Lodge was decidedly pro-Hanoverian and

its proscription against political controversy really amounted to a

support of the Hanoverian status quo.

In light of the Machiavellian nature of Brotherhood activity, if we

were to view the Mother Grand Lodge as a Brotherhood faction

designed to keep alive a controversial political cause (i.e.,

Hanoverian rule in Britain), we would expect the Brotherhood network

to be the source of a faction supporting the opposition. That is

precisely what happened. Shortly after the founding of the Mother

Grand

Lodge, another system of Freemasonry was launched that directly

opposed the Hanoverians!

When James II was unseated by the Glorious Revolution of 1688, he

fled England. His followers promptly formed organizations to help him

recover the British throne. The most effective and militant group

was the Jacobite organization. Headquartered in Scotland and

Catholic Ireland, the Jacobites were able to rally widespread

support for the Stuarts. They staged many uprisings and military

campaigns against the Hanoverians, although they were ultimately

unsuccessful in recrowning the Stuarts. When the unsuccessful James

II died in 1701, his son, the self-proclaimed James III, continued

the family struggle to regain the British throne. A new branch of

Freemasonry was created to assist him. That branch was patterned

after the old Knights Templar.

The man who reportedly founded Knights Templar Freemasonry was one

of James Ill’s loyal supporters, Michael Ramsey. Ramsey was a

Scottish mystic who had been hired by James III to tutor James’ two

sons in France.

Ramsey’s goal was to re-establish the disgraced Templar Knights in

Europe. To accomplish this, Ramsey adopted the same approach used by

the Mother Grand Lodge system of London: the resurrected Knights

Templar were to be a secret mystical/fraternal society open to men

of varied occupations. The old knightly titles, uniforms, and “tools

of the trade” were to be used for symbolic, fraternal and ritual

purposes within a Masonic context. In keeping with these aims, Ramsey

dubbed himself the Chevalier [Knight] Ramsey.

Ramsey did not work alone. He was assisted by other Stuart

supporters. Among them was the English aristocrat, Charles Radcliffe. Radcliffe was a zealous Jacobite who had been arrested

with his brother, the Earl of Derwentwater, for their actions in

connection with the failed rebellion of 1715 to place James III on

the British throne. Both brothers were sentenced to death. The Earl

was beheaded, but Radcliffe escaped to France.

In France, Radcliffe assumed the title of Earl of Derwentwater. He

presided over a meeting in 1725 to organize a new Masonic lodge based

on the Templar format

being revealed by Ramsey. The Derwentwater lodge was instrumental in

getting the new Templar system of Freemasonry going in Europe.

Derwentwater claimed that the authority to establish his Lodge came

from the Kilwinning Lodge of Scotland—Scotland’s oldest and most

famous lodge.*

* There is some debate as to whether Lord Derwentwater had also

received a charter from the Mother Grand Lodge of England to start

his new French lodge. Many histories state that he did, but some

Masonic scholars aver that no record of such a charter exists and

that Lord Derwentwater’s lodge was an unofficial (“clandestine”)

lodge.

.

It has been argued that the Mother Grand Lodge of England

would not have granted Derwentwater a charter because his pro-Stuart

political leanings were well known.

.

As a footnote, Lord Derwentwater “continued to remain politically

active and he tried to join Charles Edward during the Jacobite

rebellion of 1745. The ship on which Derwentwater sailed was

captured by an English cruiser. The Earl was taken to London where

he was beheaded in December 1746.

Templar Freemasonry is therefore often called

Scottish Freemasonry because of its reputed Scottish origin.

Ramsey’s Scottish Masonry attracted many members by claiming that the

Templar Knights had actually secretly created the Mother Grand Lodge

system. According to Ramsey, the Knights Templar had rediscovered

the “lost” teachings of Freemasonry centuries earlier in the Holy

Land during the Crusades. They brought the teachings back to Europe

and, after their disgrace and banishment, secretly kept the

teachings alive for hundreds of years in France, England, and

Scotland. After centuries of living in the shadows, the Templars

cautiously re-emerged by releasing only the Blue Degrees through the

vehicle of the Mother Grand Lodge.

Ramsey claimed that the three

Blue Degrees were issued only to test the loyalty of Freemasons.

Once a Freemason proved his loyalty by reaching the third degree, he

was entitled to advance to the “true” degrees: the fourth, fifth, and

higher degrees released by Ramsey. Ramsey stated that he was

authorized to release the higher degrees by a secret Templar

headquarters in Scotland.

According to his story, the

Scottish Templars were secretly working through the lodge at Kilwinning.

To effect their pro-Stuart political aims, the Scottish lodges

changed the Biblical symbolism of the third Blue Degree into

political symbolism to represent the House of Stuart. Ramsey’s

“higher” degrees contained additional symbolism “revealing” why

Freemasons had a duty to help the Stuarts regain the throne of

England. Because of this, many people viewed Scottish Freemasonry as

a clever attempt to lure Freemasons away from the Mother Grand Lodge

system which supported the Hanoverian monarchy and turn the new

converts into pro-Stuart Masons.

The Stuarts themselves joined Ramsey’s organization. James III

adopted the Templar title “Chevalier St. George.” His son, Charles

Edward, was initiated into the Order of Knights Templar on September

24, 1745, the same year in which he led a major Jacobite invasion of

Scotland. Two years later, on April 15, 1747, Charles Edward

established a masonic “Scottish Jacobite Chapter” in the French

city of Arras.

Charles Edward later denied ever having been a

Freemason in order to squelch damaging rumors that Scottish Masonry

was nothing more than a front for the Stuart cause (which it largely

was), even though he had been a Grand Master in the Scottish system.

Proof of his Grand Mastership was discovered in 1853 when someone

found the charter issued by Charles Edward to establish the

above-mentioned lodge at Arras. The charter states in part:

We, Charles Edward, King of England, France, Scotland, and Ireland,

and as such Substitute Grand Master of the Chapter of H., known by

the title of Knight of the Eagle and Pelican .. .*

• “Chapter of H” is believed to have been the Scottish lodge at

Heredon. Charles Edward is denoted as the “Substitute” Grand Master

because his father, as King of Scotland, was considered the

“hereditary” Grand Master.

We have just discussed the founding of two systems of Freemasonry.

Each one supported the opposite side of an

important political conflict going on in England—a conflict which

affected other European nations, as well. Both systems of Freemasonry

were launched within less than five years of one another. Ramsey’s

story of how the two systems came into existence therefore contains

some rather stunning implications. His story implies that a small

hidden group of people belonging to the Brotherhood network in

Scotland deliberately created two opposing types of Freemasonry to

encourage and support both sides of a violent political controversy.

This would be a startlingly clear example of Machiavellianism.

How true is Ramsey’s story? To answer this question, we must first

take a brief look at the history of Freemasonry in Scotland.

Scotland has long been an important center of Masonic activity. The

earliest of the old Masonic guilds in Scotland had been founded at

Kilwinning in 1120 A.D. By 1670, the Kilwinning Lodge was already

practicing speculative Freemasonry (although, in name, it was still

an operative lodge).

The Scottish lodges were unique in that they were independent of,

and were never chartered by, the English Grand Lodge even after they

began to practice the Blue Degrees of the English Grand Lodge

system. The Kilwinning Lodge itself had been granting charters since

the early 15th century. It ceased doing so only in 1736 when it

joined other Scottish lodges in elevating the Edinburgh Lodge to the

position of Grand Lodge of Scotland. The new Grand Lodge of

Scotland

at Edinburgh adopted the speculative system of the English Grand

Lodge, yet it still remained independent of the English Grand Lodge

and issued its own charters.

About seven years later, in 1743, the Kilwinning Lodge broke away from the Grand Lodge of Scotland over a

seemingly trivial dispute. Kilwinning set itself up as an

independent Masonic body (“Mother Lodge of Kilwinning”) and once

again issued its own charters. In 1807, the Kilwinning Lodge

renounced all right of granting charters and rejoined the Grand

Lodge of Scotland. We therefore see substantial periods of time

in which the Kilwinning Lodge was independent of all other Lodges and

when it could very well have granted charters to Templar Freemasons.

It was independent at the time Ramsey and Derwentwater claimed to

have received authorization from Kilwinning to establish Templar

degrees in Europe.

Some masonic historians argue that the Kilwinning Lodge and other

Scottish lodges still had nothing to do with creating the so-called

“Scottish” degrees. They state that the Scottish degrees were all

created in France by Ramsey and his Jacobite cohorts. Some Masonic

writers contend that Templarism did not even reach Scotland until

the year 1798—decades after it had already caught on in Europe.

Those writers further claim that the Kilwinning Lodge had never

practiced anything but the Blue Degrees of the English system.

Others believe that Ramsey, who was born in the vicinity of Kilwinning, claimed a Scottish origin to his degrees out of

nationalistic pride and to help build a base of political support

for the Stuarts in Scotland. These arguments sound persuasive, but

historical documentation proves that they are all false.

First of all, we have already seen that Scotland was providing this

era with important historical figures contributing to some of the

changes being wrought by Brotherhood revolutionaries. Michael

Ramsey is the third mysterious Scotsman of obscure origin we have

seen help bring important changes to Europe. The other two were

discussed earlier: William Paterson, who helped German rulers set up

a central bank in England, and John Law, who was the architect of

the central bank of France.

Secondly, the Scottish masonic lodges were a natural place for

pro-Stuart Templar degrees to arise. Scotland was strongly pro-Stuart

and the Jacobites were headquartered there.

Decades before the

English Grand Lodge was created, many Masons in Scotland were

already known to be helping the Stuarts. These Scottish loyalists

used their lodges as secret meeting places in which to hatch

political

intrigues. Pro-Stuart Masonic activity may go as far back as 1660—the

year of the Stuart Restoration (when the Stuarts took the throne

back from the Puritans). According to some early Masons, the

Restoration was largely a Masonic feat. General Monk, who played

such a pivotal role in the Restoration, was reported to be a

Freemason.

Finally, there is incontroverted evidence that the Scottish lodges,

including the one at Kilwinning, were involved with Templarism

decades before 1798. Masonic historian Albert Mackey reports in his

History of Freemasonry that in 1779, the Kilwinning Lodge had issued

a charter to some Irish Masons who called themselves the “Lodge of

High Knights Templars.” More than a decade earlier, in 1762, St.

Andrew’s Lodge of Boston had applied to the Grand Lodge of Scotland

for a warrant (which it later received) by which the Boston lodge

could confer the “Royal Arch” and Knight Templar degrees at its

August 28, 1769 meeting. It is significant that St. Andrew’s Lodge

had applied to the Grand Lodge of Scotland for the right to confer

the Templar degree, not to any French lodge.

We have thus confirmed two elements of Ramsey’s story:

1) that

Scottish lodges practiced Templar Freemasonry, and

2) that a Scottish

Grand Lodge was granting Templar charter sat least as early as 1762.

We can safely assume that the Scottish Grand Lodge was involved with

Templarism before that year because the Lodge would have had to

establish the Templar degree before another lodge could apply for

it. Unfortunately, there are no apparent records surviving to

indicate just when Templarism began in the Scottish lodges. Ramsey

and Derwentwater, of course, claim that the Templar degrees already

existed in the early 1720’s.

The Scottish lodges may well have been

involved with some form of Templarism at that time.

Understandably, the Scottish lodges were highly secretive about

their Templar activities. We only know about the 1762 Templar

charter to St. Andrew’s Lodge from records found in Boston. One need

only consider the fates of the two Earls of Derwentwater to

appreciate the dangers awaiting those people, including Freemasons,

who engaged in pro-Stuart political activity.

Not every element of Ramsey’s Templar story was backed by evidence.

For example, Freemasonry itself was not started by the Templar

Knights as Ramsey implied. The masonic guilds which gave birth to

Freemasonry existed long before the Templar Knights were founded. On

the other hand, there is circumstantial evidence that Templar

Knights may

indeed have been the ones who brought the Blue Degrees to England.

As mentioned in Chapter 15, it is thought that the three Blue

Degrees were already being practiced centuries earlier by the

Assassin sect of Persia. The Templar Knights had frequent contact

with the Assassins during the Crusades. During those periods when

they were not fighting against one another, the Assassins and

Templars established treaties and engaged in other amicable

relations. One treaty even allowed the Templars to build several

fortresses on Assassin territory. It is believed by some historians

that during those peaceful interludes, the Templars learned about

the Assassins’ extensive mystical teachings and incorporated some of

those teachings into the Templar system. It is therefore quite

possible that the Templars did indeed have the Blue Degrees long

before they were established by the English Mother Grand Lodge.

Further circumstantial evidence is that during the Crusade era, the

Templars were at the height of their power in Europe. They owned

properties throughout the Continent. Their holdings and

preceptories in Scotland were especially numerous. When the Templars

abandoned the Holy Land after the Crusades, they eventually

returned to their preceptories around the world, including Scotland.

After the Templar Order was suppressed throughout Europe, many

Templars refused to abandon their Templar traditions and so they

conducted their activities in secrecy. Some secretly-active

Templar joined Masonic lodges, including lodges in Scotland

and England. It is therefore conceivable that Templars were the

conduit through which the three Blue Degrees traveled from the

Assassin sect, through Scotland, to the Mother Grand Lodge of 1717.

Some Freemasons may view any attempt to connect the Blue Degrees

with

the Assassins sect as an effort to discredit Freemasonry, even

though the connection was suggested by one of Masonry’s most

esteemed historians. In discussing such a link, it is important to

keep in mind that the assassination techniques employed by the

Assassins were never taught in the Blue Degrees. The Assassins

possessed an extensive mystical tradition that extended well beyond

their

controversial political methods. Furthermore, the Assassins had

borrowed many of their mystical teachings from earlier Brotherhood

systems. The Blue Degrees may have therefore begun even earlier

than the founding of the Assassin organization.

Whatever the ultimate truth of the origins of the Blue Degrees and

Scottish Degrees may have been, both systems gained great popularity.

The Scottish Degrees eventually came to dominate nearly all of

Freemasonry. On continental Europe, the center of Scottish

Freemasonry proved to be Germany, where the same small clique of

German petty princes we have been observing soon emerged as

leaders in the new Templar Freemasonry.

Back to Contents

Back to Masons and Knights Templar

The “King Rats”

THROUGHOUT ALL OF history, small groups of official and economic

elites belonging to the mystical Brotherhood network have profited

from the conflicts generated by the network. If ancient Mesopotamian,

American and biblical writings are correct, then those human elites

are really only at the top of a prisoner hierarchy. We might label

those elites the “King Rats” of Earth.

The term “King Rat” comes from a James Clavell novel which was later

made into a Hollywood movie starring George Segal. The story King

Rat concerns a group of American and British soldiers being held

captive in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp during World War II.

Through clever bargaining and organization, one of the American

prisoners, Corporal King, manages to amass a wealth of material

goods desperately craved by the other prisoners of war.

As a result,

he sits at the top of the prisoner hierarchy and is often able to

buy loyalty with a cigarette or fresh egg. The other prisoners simply

call him King, for that is what he is inside the prison. When

he embarks on a venture to breed rats as food, he earns the title

“King Rat,” which somehow seems to fit him.

King Rat enjoys every luxury craved by the other prisoners, yet the

fact remains that he is still a prisoner himself. King Rat can only

remain at the top of the pecking order so long as everyone remains

imprisoned. At the end of the film, when the war is over and the camp

is liberated, he no longer has the prison environment he relied on to

stay on top. In freedom, he is lost, wondering if he really welcomes

the liberation. In the final scene of the movie we see him being

driven off in a truck, just another corporal. We sense, however,

even if King Rat does not, that he is better off liberated since

the fragile fiefdom he had built could have been easily toppled at

any time by the Japanese prison keepers. King’s life as a liberated

corporal is far more secure than his precarious existence at the top

of an oppressed prison population.

The King Rat of cinema was ultimately a sympathetic character. Those

whom we might label the “King Rats” of Earth are not so endearing

for we will use the term to describe only those individuals who

acquire their profits and influence not by breeding rats, but by

helping to breed war and suffering for human consumption.

For thousands of years, Earth has had endless successions of “King

Rats.” In this chapter, we will look at a particularly interesting

group of them: the petty princes of 18th-century Germany. They and

their relationship to Brotherhood mysticism provide a fascinating

look at a curious element of 18th-century politics—politics which

have done much to shape the social, political and economic world we

live in today.

Germany became the center of Templar Freemasonry on continental

Europe. The Knight degrees took on a unique character in the German

states where the degrees were made into a system of Freemasonry

called the “Strict Observance.” The “Strict Observance” was so named

because every initiate was required to give an oath of strict and

unquestioning obedience to those ranking above him within the Order.

The vow of obedience extended to a mysterious figure known as the

“Unknown Superior,” who was said to be

the secret leader of the Strict Observance and who was reportedly

residing in Scotland.

Members of the Strict Observance first passed through the Blue

Degrees before they were initiated into the higher degrees of

“Scottish Master,” “Novice,” “Templar,” and ”Professed Knight.” The

“Unknown Superior” went by the title “Knight of the Red Feather.”

Although secrecy in the Strict Observance was very strong, several

leaks revealed that the Strict Observance was true to the Scottish

degrees by agitating against the House of Hanover in favor of the

Stuarts.

The Strict Observance spread quickly throughout the German states

and became the dominant form of Freemasonry there for decades. It

also became influential in other countries such as France, which

was the second largest center of Freemasonry in Europe. (Germany was

the largest.) In all nations, Strict Observance members pledged

obedience to the “Unknown Superior” of Scotland.

According to J. M.

Roberts, writing in his book,

The Mythology of the Secret Societies:

The Strict Observance evoked suspicion and hostility in France

because of its German origins and great excitement was aroused by the

implied recognition by the Grand Orient [France’s supreme Masonic

body] of the authority of the unknown superiors of the

Strict Observance over French freemasons.1

One of the earliest Grand Masters of the Strict Observance was G. C. Marschall. Upon Marschall’s death in 1750, the position was assumed

by a German from Saxony: the Baron Von Hund. The Strict Observance

degrees had nearly all been created by the beginning of Von Hund’s

Grand-Mastership, but Von Hund has been given credit for doing the

most to put them into recognizable form. Von -Hund stated that he

had been initiated into the Order of the Temple (i.e. the Templar

Knights) by Lord Kilmarnock, a prominent nobleman from Scotland. Von Hund also claimed that he had met both the “Unknown Superior” and

Charles Edward.

Like Michael Ramsey, Von Hund was on a mission to reestablish the

Templar Knights in Europe. Von Hund sought to raise money to

repurchase the lands which had been seized from the Templars

centuries earlier. Although Von Hund had many successes, he was

branded a fraud by his enemies and he eventually fell into disgrace.

The Strict Observance gained a strong following among the German

royal families (although some opposed it and remained loyal to the

English Masonic system). This is a puzzle. Some royal families

involved in the Strict Observance were politically allied to

Hanover. Why would they participate in a form of Freemasonry which

secretly opposed the English House of Hanover?

In some cases, it appears that the royal members had joined the

Strict Observance after it ceased to be virulently pro-Stuart.

Certainly the Stuart cause was waning by the 1770’s when some of

those German princes emerged as Strict Observance leaders. On the

other hand, there is another important factor to be considered:

The woes of England caused by the Stuart rebellion and by other

conflicts were a source of immense profit to those German

principalities, including to Hannover! That same small clique of

German royal dynasties which had been marrying into foreign royal

families and then overthrowing them, made big money from the

conflicts which they helped to create—conflicts which were also being

stirred up by the Brotherhood network.

To better understand this situation, we must briefly digress and

review the history of the Teutonic Knights after they were defeated

in the Crusades.

When the Crusades ended, the Teutonic Knights, like the Templar and Hospitaler Knights, found work elsewhere. In 1211, while under the

leadership of Grand Master Hermannvon Salza, the Teutonic Knights

were invited to Hungary to aid a struggle going on there. For their

services, they were awarded the district of Burzenland in

Transylvania, which was then under Hungarian rule. The Knights

outlived their welcome, however, and were expelled because they

demanded too much land. After their ouster from Transylvania, the

Knights were invited by Conrad, Polish

Prince of Masovia, to help fight heathen Slavs in Prussia. The

Knights were again rewarded with land. This time they received large

sections of Prussia.

The Knights gained another benefactor: German Emperor Frederick

II—the man who made the ten-year peace treaty we discussed in

Chapter 15. Although Frederick had acted as a man of peace, he was

unfortunately also associated with this organization of war. In

1226, Frederick empowered the Knights to become overlords of

Prussia. Frederick awarded to Grand Master von Salza the status of a

prince of the German Holy Roman Empire. Frederick was also

responsible for a reorganization of the Order.

The Teutonic Knights were thoroughly entrenched in Prussia by the

year 1229. They built solid fortresses and imposed Christianity on

the native Prussian populace with an energetic military campaign. By

1234, the Knights were politically autonomous and served under no

authority except the Pope. The Knights surrendered their extensive

Prussian holdings to the Pope in name and received them back as

fiefs. In reality, the Teutonic Knights were the true rulers of

Prussia, not the Pope.

With Papal support, the ranks of the Teutonic Knights ballooned

rapidly. Many Germans traveled to Prussia to enter the new and

potentially lucrative theatre of war.

This migration eventually

brought about the complete ”Germanization” of Prussia. Commerce and

industry eventually replaced armed conflict and Prussia became a

major commercial center. By the early 1300’s, the dominion of the

Teutonic Knights extended over most of the southern and southeastern

coastline of the Baltic Sea. The Teutonic Knights had two centuries

in which to leave their indelible mark on central and western

Europe. Before losing power, the Knights had established the

militant character of Prussia that would define that region for

centuries to follow.

By the early 1500’s the fate of the Teutonic Knights had worsened.

They were driven out of West Prussia by Poland and were forced to

rule East Prussia as a Polish fief. By 1618, Prussia fell completely

under the rule of the Hohenzollern dynasty. This effectively marked

the end of autonomous Teutonic Knight rule.

Despite continuing friction between the Knights and the

Hohenzollerns over control of Prussia, the Hohenzollerns kept

significant elements of the Knight organization alive. At least one

Hohenzollern, Albert of Brandenburg-Anspach, had been a Grand Master

of the Order around 1511. Hohenzollern Prussia adopted the colors of

the Teutonic cloaks (black and white) as the official hues of the

land. The two-headed Teutonic bird became Prussia’s national symbol.

Like the other knightly organizations of the Crusades, the Teutonic

Knights were eventually turned into a secret fraternal society, this

time under the sponsorship of the royal Hapsburg family of Austria.

The Teutonic Knights still survive in that form today.

Under the rule of the Hohenzollerns, the power and influence of

Prussia grew. Prussia became a formidable player in the tangled

political arena of Europe. By the eighteenth century, the

Hohenzollerns had also become extensively intertwined with their

German royal neighbors through marriage. For example, history’s

most famous Hohenzollern, Frederick II (better known as “Frederick

the Great”), had been set up by his father in 1733 to marry

Elizabeth Christina of the northwestern German principality of

Brunswick. (In 1569, the Brunswick dynasty had founded the

Brunswick-Luneburg family line which later became the Hannover

family.) Frederick’s mother was Sophia Dorothea, sister of

Hanoverian King George II. Generations earlier, Frederick the

Great’s great grandfather had married Henrietta, daughter of the

Prince of Orange.

Political marriages, because they were usually loveless, were often

unsatisfactory to those who were wed. This proved true in the joining

of Frederick the Great to Elizabeth Christina of Brunswick. Frederick

had wanted to marry one of the Hanoverians, but his father’s stern

will prevailed. Despite this unhappy arrangement, Frederick still

had amicable ties to others in the Brunswick family. It was in

Brunswick that Frederick, not yet the King of Prussia, was secretly

initiated into Freemasonry on August 14, 1738 against his father’s

wishes. The initiation had been authorized by the Lodge of Hamburg

in Hannover. The Lodge practiced the Blue Degrees of English

Freemasonry.

Two years after his initiation, Frederick II became the king of

Prussia. He then publicly revealed his Masonic membership and

initiated others into the Order.* At Frederick’s command, a Grand

Lodge was established in Berlin called Lodge of Three Globes. Its

first meeting was held on September 13, 1740. This Lodge began as an

English system lodge and it had the authority to grant charters.

*In 1740, Frederick initiated several other important German nobles

into Freemasonry: his brother, Prince William; the Margrave (Prince)

Charles of Brandenburg (whose family was also married into the House

of Hanover through Caroline of Brandenburg as wife to King George

II); and Frederick William, the Duke of Holstein.

How long Frederick remained active in Freemasonry is still debated

today. Some historians believe that he ceased his Masonic activities

in 1744 when the demands of war occupied his full attention. His

general cynicism later in life eventually extended to Freemasonry.

Nevertheless, Frederick’s name continued to appear as the authority

for Masonic charters even after he was reportedly inactive. It is

uncertain whether Frederick merely lent his name to the granting of

charters or was personally involved in the process.

Within about a decade of Frederick’s Masonic initiation, the

Strict

Observance and its Scottish degrees were in the process of almost

completely taking over German Masonry. Frederick’s Lodge of Three

Globes became decidedly “Strict Observance” when its new statutes

were adopted on November 20, 1764. On January 1, 1766, Baron VonHund,

Grand Master of the Strict Observance, constituted the Three Globes

as a Scots or Directoral Lodge empowered to warrant other Strict

Observance Lodges. All lodges already warranted by the Three Globes

except one (the Royal York Lodge) went over to the Strict Observance

(Scottish) system.

Whatever Frederick’s masonic involvement may or may not have been,

he and his Prussian kingdom profited from the conflicts of England

that Scottish Masonry had been

contributing to.

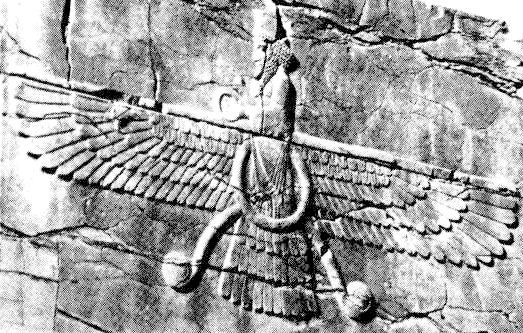

An ancient Mesopotamian depiction of one of their female

extraterrestrial “Gods.”

The “Gods” were very

humanlike with male and female bodies. The eyewear, form-fitted

clothing, and body

apparatus on the above “God” are strongly reminiscent of

modern aviator’s goggles, airtight suit, and modern gadgetry.

(Reproduced by permission from

The Twelfth Planet, by

Zecharia Sitchin.)

The Great Pyramid is also pointed precisely along the four compass

directions. This postage stamp issued by Egypt in 1959 shows an

airplane flying in direct alignment with the Great Pyramid, as

though to suggest that the pilot is using the pyramid to guide the

airplane.

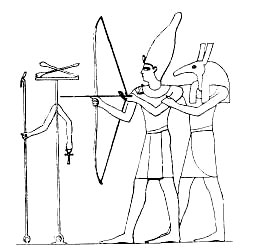

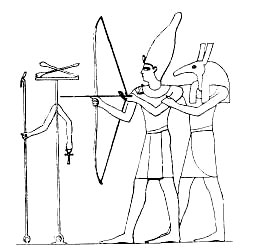

Egypt’s

Custodial “Gods” were said to participate in the up-bringing

of the pharaohs. In this Egyptian illustration we see Pharaoh

Thutmose III being given an archery lesson by one of his “Gods.”

Thutmose became famous for his military exploits.

This illustration

suggests that Custodians had a role in training humans to be

warlike.

The Custodial "gods" of ancient Egypt

were very often depicted wearing aprons.

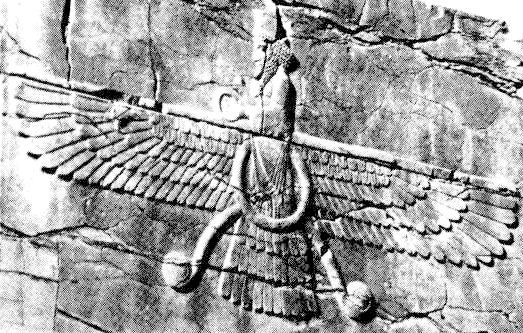

The Zoroastrian “God, “ Ahura Mazda, was depicted in ancient Persia

as a humanlike creature who flew in a circular object. The object is

depicted with stylized wings and bird’s tail to indicate that it

flies. It also had bird’s feet that look like landing struts.

Depictions such as these were not meant to be literal images of the

“God, “but were meant to portray the “God ” in such a way so as to

reveal its attributes. Zoroaster’s “God ” had the attributes of being

humanlike and flying about in a circular craft.

Grand Master of the Templar Knights,

Jacques de Molay, is led to a stake where he will be burned. Three

other Templar Knights also await execution. The burning took place

in Paris; in the background one can see the Cathedral of Notre Dame.

Christianity has been closely associated with Brotherhood mysticism

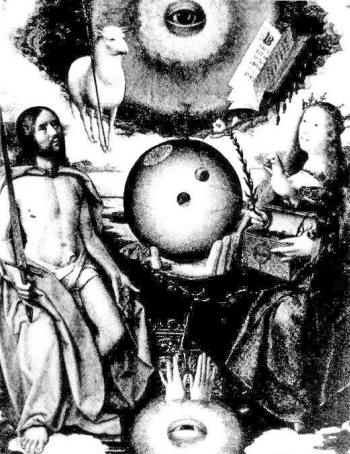

since the lifetime of Jesus. This painting by Jan Provost (ca.

1465-1529) is entitled, “A Christian Allegory.” It features

Christian symbols—among them the “All-Seeing Eye” of God and the

lamb. Both of these symbols were used by the Brotherhood long before

the advent of Christianity.

The “All-Seeing Eye” of God was derived

from the “Eye of Horus” symbol used in ancient Egypt. Horus

was one

of Egypt’s Custodial “Gods.“ The lamb was already symbolically

important during the reign of Melchizedek centuries before the birth

of Jesus. It was Melchizedek‘s branch of the Brotherhood that

reportedly first began to use lambskin for its ceremonial aprons.

The extraordinary similarities between the ancient civilizations of

Egypt and America are too striking to be coincidence. Above is the

ancient Mexican Pyramid of the Sun, which resembles the first step

pyramid of Egypt.

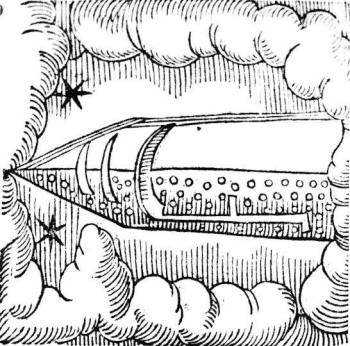

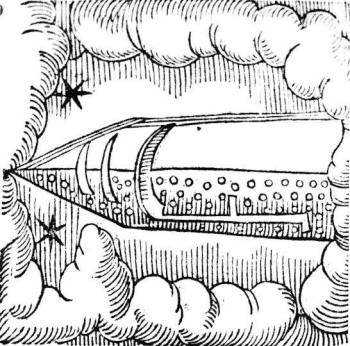

Centuries ago, almost any unusual flying object was called a

“comet.” The above is an illustration published in 1557 of a “comet”

observed in 1479 in Arabia. The comet was described as looking like

a sharply pointed wooden beam.

.

The artist’s concept, which was based

on eyewitness testimony, looks like a rocketship with numerous port

holes. Many other ancient reports of “comets” may well have been of

similar objects.

(Reproduced from 'A Chronicle of Prodigies and Portents'...

by Conrad Lycosthenes.)

ABOVE LEFT AND RIGHT: The

similarities between ancient Old and New World civilizations are

also seen in some of the symbols used by both. Above left is the Eye

of Horus symbol found in ancient Egypt. Above right is a similar eye

found on an ancient American artifact.

ABOVE AND BELOW: Many proposed designs were submitted for a flag for

the new Confederacy. These two proposals, which are preserved today

in the United States National Archives, prominently feature

the

Brotherhood’s symbol of the All-Seeing Eye. The Confederate leaders

eventually opted for a simple cross bars and stars design.

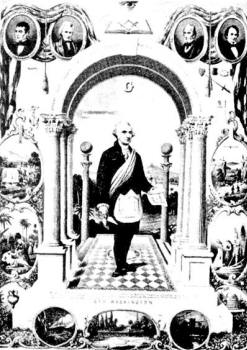

Depiction of George Washington wearing his Masonic regalia.

Despite his domestic liberalism and professed

anti-Machiavellian beliefs, Frederick proved by his actions to be as

warlike and as shrewdly manipulative in the complex web of European

politics as any man of his day. His goal was the militaristic

expansion of the Prussian kingdom. He was not above aiding

insurrection and being fickle in his alliances to achieve his goal.

In the 1740’s, Frederick had a political alliance with France.

France was actively supporting the Jacobites against the Hanoverians

and rumors circulated in London that Frederick was helping the

Jacobites prepare for their big invasion of England in 1745.

Frederick afterwards shifted his alliance back to England and

continued to profit from England’s woes. He not only gained

territory, but money as well. Sharing in Frederick’s monetary

profits were other German principalities, including Hannover

itself. They all made their money by renting German soldiers to

England at exorbitant prices. Hannover had already been engaged in

this enterprise for decades.

The rental of German mercenaries to England was perhaps one of the

great “scams” of European history: a small clique of German families

overthrew the English throne and placed one of their own upon it.

They then used their influence to militarize England and to involve

it in wars. By doing so, they could milk the British treasury by

renting expensive soldiers to England to fight in the wars they

helped to create! Even if the Hanoverians were unseated in England,

they would go home to German Hannover with a handsome profit made

from the wars to unseat them.

This may be one key to the puzzle of

why some members of this German clique supported Scottish Templar

Freemasonry and later took on leadership positions within it.

England rented German mercenaries through the signing of “subsidy

treaties,” which were really business contracts. England began

entering into subsidy treaties almost immediately after the German

takeover of their country by the House of Orange in 1688. As we

recall, one of the first things that William and Mary did after

taking the English throne was to launch England into war.

The German mercenaries were a constant burden to England. One early

mention of them is found in the correspondence of the Duke of

Marlborough.*

* Letters written by the Duke of

Marlborough are translated here into modern English.

Marlborough was an English leader fighting on the

European continent against France during the War of Spanish

Succession (1701-1714).**

**Wars of “succession” were wars sparked by

disputes over who should succeed to a royal throne. The major

European powers often got involved in these frays and turned them

into large-scale conflicts which could drag on for years.

Hannover was renting troops to England at

that time—years before Hannover took the British throne. On May 15,

1702, Marlborough discussed the need to pay the Hannoverian troops

so that they would fight:

If we have the Hanover troops, I am afraid there must be one hundred

thousand crowns given them before they will march, so that it would

be very much for the Service if that money were ready in Holland at

my coming.2

Four days later, 22,600 pounds were allocated by the English

government to pay the mercenaries.

Prussia and Hesse were also supplying mercenaries to Britain during

that war. Marlborough’s woes in getting them paid continued. Writing

from the Hague on March 26, 1703, he lamented:

Now that I am come here [the Hague] I find that the

Prussians, Hessians, nor Hanoverians have not received any of their extraordinaries [fees] .. .3

England’s next major European war was the War of Austrian Succession

(1740-1748). Frederick the Great was allied with France against

England this time. This did not stop other German principalities

from continuing their business relationship with England, especially

Hannoverand Hesse. Although Hannover now sat on the British

throne, it was not about to cease its profitable enterprise. If

anything, Hannover’s British reign gave that German principality

greater leverage to drive even harder bargains with England for

Hannoverian mercenaries.

A letter written on December 9, 1742 by

Horace Walpole, Britain’s former Prime Minister, discussed the

enormous fee England was asked to pay for renting 16,000 Hannoverian

troops:

. . . there is a most bold pamphlet come out... which affirms that in

every treaty made since the accession [to the British throne] of

this family [Hanover], England has been sacrificed to the interests

of Hanover. . .4

The pamphlet mentioned by Walpole contained these amusing words:

Great Britain hath been hitherto strong and vi[g]orous enough to bear

up Hanover on its shoulders, and though wasted and wearied out with

the continual fatigue, she is still goaded on . . . For the

interests of this island [England] must, for this once, prevail, or

we must submit to the ignominy of becoming only a money-province to

that electorate [Hannover].5

In the end, opposition to the subsidy treaties

failed. England truly

became Hannover’s “money-province.”

Lamented Walpole:

We have every now and then motions for

disbanding Hessians and

Hanoverians, alias mercenaries; but they come to nothing.6

The subsidy treaties were indeed lucrative. For example, in the

contract year beginning December 26, 1743,the British House granted

393,733 pounds for 16,268 Hannoverian troops. This may not seem like

much until we realize that the value of the pound was very much

higher than it is today. To raise some of this money, the

Parliament went as far as to authorize a lottery.

At the same time that England was fighting the War of Austrian

Succession, it was also fighting the Jacobites. More German troops

were needed on that front.

On September 12, 1745, Charles Edward of the Stuart family led his

famous invasion of England by way of Scotland. “Bonnie Prince

Charlie,” as Charles Edward was called, captured Edinburgh on

September 17 and was approaching England with the intent of taking

London. That meant more money for Hesse. On December 20, 1745,

Hanoverian King George II announced that he had sent for 6,000

Hessian troops to fight in Scotland against Charles Edward.

King

George presented Parliament with a bill for the Hessian troops. It

was approved. The Hessians landed on February 8 of the following

year. Meanwhile, back on the European front, England hired more

soldiers from Holland, Austria, Hannover, and Hesse to pursue

England’s “interests” there. The bills were staggering.

The war on the Continent finally ended. It was not long, of course,

before the rulers of Europe were involved in another one. This time

it was the Seven Years War (1756-1763)— one of the largest armed

conflicts in European history up until that time.*

* The Seven Years War was actually an expansion of the French and

Indian War being fought in North America between England and France.

The expansion of the war into Europe had been triggered by Frederick

the Great himself when he invaded Saxony.

Frederick of

Prussia had switched his allegiance back again to England, and the

two nations (England and Prussia) were pitted against France,

Austria, Russia, Sweden, Saxony, Spain, and the Kingdom of

Two Sicilies. Frederick did not ally himself to England this time out

of fickle love for Britain. England was paying him. By the Treaty of

Westminster effective April 1758, Frederick received a substantial

subsidy from the English treasury to continue his fighting, much of

it to defend his own interests! The treaty ran from April to April

and was renewable annually.

During the Seven Years War, England also paid out money

to help Hannover defend its own German interests. France had

attacked Hannover, Hesse, and Brunswick. Some of the subsidy money

paid to Hannover and Hesse was used by those principalities to

defend their own borders. The treaty with Hesse, signed on June 18,

1755 (shortly before the Seven Years War erupted) was especially

generous. In addition to “levy money” (money used to gather an

army together) and “remount money” (money used to acquire fresh

horses), Hesse was granted a yearly subsidy of 36,000 Pounds when

its troops were under German pay, and double that when they entered

British pay. An additional 36,000Pounds went directly to the coffers

of the Landgrave of Hesse.

Many English Lords did not feel that German troops were worth the

money. While discussing a possible French invasion of England,

Walpole joked,

“if the French do come, we shall at least have

something for all the money we have laid out on Hanoverians and

Hessians!”7

William Pitt, another influential English statesman,

added these amusing words to the debate:

The troops of Hanover, whom we are now

expected to pay, marched into

the Low Countries, where they still remain. They marched to the place

most distant from the enemy, least in danger of an attack, and most

strongly fortified had an attack been designed. They have,

therefore, no other claim to be paid than that they left their own

country for a place of greater security. I shall not, therefore, be

surprised, after such another glorious campaign... to be told

that the money of this nation cannot be more properly employed than in

hiring Hanoverians to eat and sleep.8

The German principality to profit most from the soldiers-for-hire

business was Hesse.

In taking a quick look at the history of Hesse, we find that after

Philip the Magnanimous died in 1567,Hesse was divided between

Philip’s four sons into four main provinces: Hesse-Kassel (often

spelled Hesse-Cassel), Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Rheinfels, and

Hesse-Marburg. The most important and powerful of these four Hessian

regions became Hesse-Kassel, into which Hesse-Rheinfels and

Hesse-Marburg would later be reabsorbed.

Renting mercenaries to England became the Hessian royal family’s

most lucrative enterprise. Although Hesse itself was scarred during

some of the European conflicts, the Hessian dynasty built an immense

fortune from the soldier business. In fact, Landgrave Frederick II of

Hesse-Kassel (not to be confused with Frederick II of Prussia or

with the German emperor Frederick II of the Crusade era) made

Hesse-Kassel the richest principality in Europe by renting out

mercenaries to England during Britain’s next great struggle: the War

for American Independence, also known as the American Revolution.

Also benefiting from the American Revolution was the royal House of

Brunswick. Its head, Charles I, rented soldiers to England at a very

handsome price to help fight the rebelling colonists.

As we can see, Hesse, Hannover and a few other German states

profited handsomely from the conflicts which had beset England. The

problems of Britain gave them the opportunity to plunder the British

treasury at the expense of the English people. This had the

additional effect of pushing England into ever-deepening debt to the

new bankers with their inflatable paper money.

The populace of Germany also suffered. Most of the mercenaries rented

to England were young men involuntarily conscripted and forced to

fight where their leaders sent them. Many were maimed and killed so

that their rulers could live in greater luxury. The wealth and

influence of a small clique of German dynasties had been built upon

the blood of the young.

Lurking behind these activities we continue to find the presence of

the Brotherhood network. As the years progressed, members of the

royal families of Hesse and Brunswick emerged as leaders of the

Strict Observance. In 1772, for example, at a Masonic congress in

Kohlo, Duke Charles William Ferdinand of Brunswick was chosen to

succeed Von Hund as Grand Master of the Strict Observance.*

* With the election of Duke Ferdinand, the Strict Observance

underwent several changes. The Strict Observance was informally

called the “United Lodges.” Another congress was held ten years

later in 1782 in Wilhelmsbad (a city near Hanau in Hesse-Kassel).

There the name “Strict Observance” was dropped altogether and the

Order was thereafter called the “Beneficent Knights of the Holy

City.” The Wilhelmsbad congress officially abandoned the story that

the Templar Knights were the original creators of Freemasonry.

However, the Knight degrees were retained, as was the idea of

leadership by an “Unknown Superior.”

Several years after his election to the Grand Master

position, Duke Ferdinand succeeded Charles I as the ruler of

Brunswick and inherited the money from Brunswick’s rental of

mercenaries.

Sharing leadership duties in the Strict Observance with the Duke of

Brunswick was Prince Karl of Hesse, son of Frederick II of

Hesse-Kassel. According to Jacob Katz in his book, Jews and

Freemasons in Europe, 1723-1939, Prince Karl was later “accepted as

the head of all German Freemasons.”9

Karl’s brother, William IX, who

later inherited the principality and immense fortune of Hesse-Kassel from their father, was also a Freemason. William IX had

provided mercenaries to England when he earlier ruled Hesse-Hanau.

How important a role did the Brotherhood itself really play in

manipulating these affairs?

To determine if there truly was active

Brotherhood involvement of a Machiavellian nature, it would help to

discover if there was any single Brotherhood agent who participated

first in one faction and then in another. We would require a

Brotherhood agent traveling in all circles: from the Jacobites to

the electors of Hesse, from the King of France to Prussia.

Interestingly, history records just such an individual. We would not

normally learn of such an agent because of the secrecy surrounding

Brotherhood activity. This particular person, however, by virtue of

his flamboyant personality, his remarkable artistic talents, and his

flair for drama, had attracted so much attention to himself that his

activities and travels were noted and recorded for posterity by many

of

the people around him.

Deified by some and declared a charlatan by

others, this flamboyant agent of the Brotherhood was best known by

a false appellation: the Count of St. Germain.

Back to Contents

|