|

Naval Warfare

The old notion that the Hindus were essentially a landlocked people,

lacking in a spirit of adventure and the heart to brave the seas, is

now dispelled. The researches of a generation of scholars have

proved that from very early times the people of India were

distinguished by nautical skill and enterprise, that they went on

trading voyages to distant shores across the seas, and even

established settlements and colonies in numerous lands and islands.

In ancient India, owing to the geographical influence, nautical

shill and enterprise seems to have been best developed in three

widely separated region of the country. These were Bengal, the

valley and delta of the Indus, and the extreme south of the Deccan

peninsula, called Tamilagam.

Boat-making and ship-building industries were found in India since

ancient times. In the Vedic period, sea was frequently used for

trade purposes. The Rig Veda mentions "merchants who crowd the great

waters with ships". The Ramayana speaks of merchants who crossed the

sea and bought gifts for the king of Ayodhya. Manu legislates for

safe carriage and freights by river and sea. In some of the earliest

Buddhist literature we read of voyages ‘out of sight’ of land, some

lasting six months or so.

In Kautalya Arthasastra the admiralty figures as a separate

department of the War Office; and this is a striking testimony to

the importance attached to it from very early times. In the Rg Veda

Samhita boats and ships are frequently mentioned. The classical

example often quoted by every writer on the subject is the naval

expedition of Bhujya who was sent by his father with the ship which

had a hundred oars (aritra). Being ship-wrecked he was rescued by

the twin Asvins in their boat.

"There was also extensive intercourse of India with foreign

countries, including the Mediterranean lands and the African

continent, naturally led to piracy on the waters. There then arose

the need for the protection of sea-borne trade, and we are told that

“at the outset the merchant vessels of India carried a small body of

trained archers armed with bows and arrows to repulse the attacks of

the pirates, but later they employed guns, cannon and other more

deadly weapons of warfare with a few wonderful and delusive

contrivances.”

(source:

The Commerce and Navigation of the Ancients In the Indian

Ocean - William Vincent pp. 457). These are probably the beginnings

of the ancient Indian navy.

In the Shanti Parvan (59, 41) of the Mahabharata it is said that the

navy is one of the angas (part) of the complete army. Examples of

ships being used for military purposes are not lacking. When Vidura

scented danger to Kunti’s five sons, he made them escape to the

forest with their mother, crossing the Ganges in a boat equipped

with weapons having the power of withstanding wind and wave.

In the

Dig Vijaya portion of the Sabha parva, it is said that Sahadeva

crossed the sea and brought many islands under his sway after

defeating the Mlecchas and other mixed tribes inhabiting them. If

this be an historical fact the inference is irresistible that he

could not have effected his conquest without the use of boats and

vessels. We read in the Ramayana that Durmukha, a Raksasa, who had

been fired by the impulse of anger at the deeds of Hanuman, offered

his services to Ravana even to fight on the sea.

This is testimony

enough of the use of a fleet for war purposes. There are other

references here and there to ships in the Ramayana. When Hanuman was

crossing the ocean to Lanka, he is compared to a ship tossed by

winds on the high seas. Sugriva speaks of Sumatra, Java and even the

Red Sea, when sending

forth his monkey hosts in quest of Sita. forth his monkey hosts in quest of Sita.

The Amarakosa, mentions a number of nautical terms which stand for

ship, anchorage (naubandhana), the helm of the ship (naukarana), the

helmsman (naukaranadhara). That there were ships-building yards in

different parts could be inferred from a significant term

navatakseni occurring in a copper plate grant of Dharmaditya dated

531. A.D.

About 517 B.C. according to Herodotus, Darius launched a maritime

expedition under Skylax of Caryanda to the Indus Delta, and during

Alexander’s time, again, we read of the people of the Punjab fitting

out a fleet. We have the testimony of Arrian to show that the

Xathroi (Kshatri), one of the Punjab tribes, supplied Alexander

during his return voyage with thirty oared galleys and transport

vessels which were built by them.

(source: India and Its Invasion by Alexander p. 156)

In the Manusamhita (Vii. 192), it is laid down that boats should be

employed for military purposes when the theatre of hostilities

abounded in water. Kamandaka (XVI, 50) alludes to naval warfare when

he says:

"By regular practice one becomes an adept in fighting from

chariot, horses, elephants and boats, and a past-master in archery."

Manavadharmasastra refers to sea fights and attests to the use of

boats for naval warfare. The sailor is called naukakarmajiva. Thus

in Vedic, Epic and the Dharmasastra literature we find that naval

warfare is mentioned as a distinct entity, attesting a continuous

naval tradition from the earliest times. Yukti-kalpataru specifies

one class of ships called agramandira (because they had their cabins

towards the prows), as eminently adapted for naval warfare (rane

kale ghanatyaye).

Passing on to other literary evidence, we find in the Raghuvamsa

frequent reference to boats and ships. Raghu in the course of his

digvijaya conquered Bengal which was protected by a fleet (nausadhanotyatan).

In anther place it is mentioned that Raghu marched on Persia through

the land route, and not by the sea route, thereby showing that the

latter was the more common route.

Historian Dr. Vincent A. Smith says that ‘the creation of the

Admiralty department was an innovation due to the genius of Chandragupta.

"The Admiralty as a department of the State may have been a creation

of Chandragupta but there is evidence to show that the use of ships

and boats was known to the people of the Rg Veda. "

(source:

Early History of India - By Vincent Smith p 133).

In the following passage we have reference to a vessel with a

hundred oats.

‘This exploit you achieved, Asvins in the ocean, where

there is nothing to give support, nothing to rest upon, nothing to

cling to, that you brought Bhujya, sailing in a hundred oared ship,

to his father’s house.’

Further on in the Veda, this same vessel is described as a

plava

which was storm-proof and which presented a pleasing appearance and

had wings on its sides. Another reference informs us that Tugra

dispatched a fleet of four vessels (Catasro navah) among which was

the one referred to above. We may infer from these passages that the

Asvins were a great commercial people having their home in a far-off

island, and that their ruler Tugra maintained a fleet in the

interests of his State. There are also other references in the Rg

Veda to show that the ancient Indians were acquainted with the art

of navigation. For instance, Varuna is credited with a knowledge of

the ocean routes along which vessels sailed.

The Baudhayana Dharmasastra speaks of Samudrasamyanam and interprets

it as nava dvipantaragamanam, i.e. sailing to other lands by ships.

This very term occurs in the navadhyaksa section of the Kautaliya

Arthasastra.

The Puranas have several references to the use of ships and boats.

The Markandeya Purana speaks of vessels tossing about on the sea.

The Varahapurana refers to the people who sailed far into the ocean

in search of pearls and oysters. The ships floated daily on the

shoreless, deep and fearful waters of the ocean. We are on firmer

ground when we see in the Andhra period their coins marked with

ships. The ship building activities were great on the east coast,

and the Coromandel coast in particular. From this period to about

15th century A.D. there was a regular intercourse with the islands

of the Archipelago most of which were colonized and also with

ancient America right across the Pacific as testified to us by the

archaeological finds and inscriptions in those parts.

The Pali books of Sri Lanka like the Mahavamsa refers to ocean going

vessels carrying 700 passengers. Such frequent intercourse and

colonization through the ages could not have been effected without a

powerful fleet.

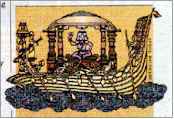

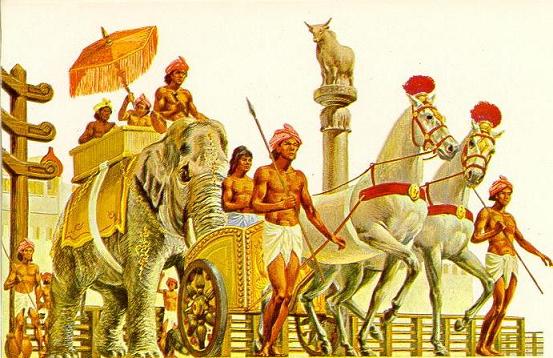

Ships Landing of Prince Vijaya in Sri Lanka - 543 BC from Ajanta

Frescos.

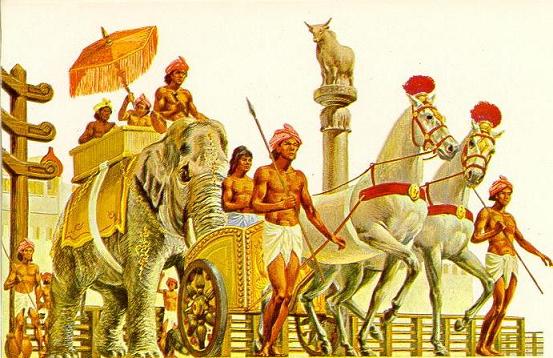

Ajanta painting of a later date depict horses and elephants

aboard the ship which carried Prince Vijaya to Sri Lanka.

(source: India Through the ages - By K. M. Panikkar).

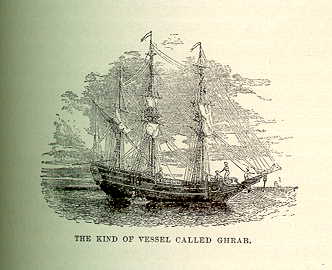

But it is in a later work, the Yuktikalpataru of Bhoja, that we have

three classes of ships - the Sarvamandira, the Madhyamandira, and

Agramandira. The first was called Sarvamandira because it had

apartments all around. In the Sarvamandira were carried treasures,

animals, and ladies of the court. This was the vessel ordinarily

used by kings in times of peace. The Madhyamandira was so called

because the living quarters were situated in the middle. It was a

sporting vessel and generally used in the rainy season. The vessel

of the third kind, the Agramandira, took its name from the

circumstance that the living room was located in front or at the top

of the vessel. The Agramandira was used for distant and perilous

voyages and also sea-fights.

There are also in the Yuktikalpataru other references to vessels.

There are 27 types of ships mentioned here, the largest having the

measurement 276 ft X 36 ft X 27 ft weighing roughly 2,300 tons. The

following passage points to the use of ships in warfare. The line:

naukadyam vipadam jneyam makes it clear that naval expeditions were

common. Under the heading of yanam or march mention is made of

expeditions by land, water and air.

Kautilya remarks:

"Pirate ships (himsrika), boats from an enemy's

country when they cross its territorial limits, as well as vessels

violating the customs and rules enforced in port towns, should be

pursued and destroyed."

It is obvious that the task set forth above

could only be performed by armed vessels belonging to the state.

From this we may conclude that in ancient India ships were employed

in warfare at least as early as the Rig Vedic times. It is an

incontrovertible fact that there was a naval department in Mauryan

times. We have the testimony of Megasthenes that the navy was under

a special officer called the Superintendent of Navigation. This

official was in turn controlled by the Admiralty department. The

officer whom Megasthenes refers to as Superintendent of Navigation

is called Navadhyaksa as already seen, in the Arthasastra.

The Greek

accounts bear testimony to the fact that navigation had attained a

very high development at the times of Alexander's invasion, for we

are told that the invader was able to secure a fleet from the Punjab

at short notice. The Arthasastra lays down some healthy regulations

relating to navigation. Vessels which gave trouble or were bound for

the enemy's country, or transgressed the regulations of port towns

were to be destroyed.

A considerable ship building activity is evident on the west coast

of India also as noted in the Sangam works of the Tamils. South

India carried on political and commercial activities as far as the

Mediterranean in the early centuries of the Christian era and

before. The great Ceran Senguttavan had a fleet under him.

Turning to the history of South India, we have evidence to show that

the country had trade and culture contacts with foreign countries

like Rome in the west and Malay Archipelago and South east Asia in

the east. Yavana ships laden with articles of merchandise visited

the west coast frequently. There was active foreign trade between

Tamil Indian and the outer world at least from the time of Soloman,

i.e. about 1000 B.C. Roman historians refer to the commercial

intercourse that existed between Rome and South India. In the first

century before Christ we hear of a Pandyan embassy to Augustus

Caesar. (refer to Periplus translated by Schoff p. 46).

The Sangam classics point to the profession of pearl-diving and

sea-fisheries on a large scale. We hear of shipwrecks of the early

Tamils saved now and then by Manimekhalai, the goddess of the sea.

(Note: ancient Tamil tradition traces its origins to a submerged

island or continent, Kumari Kandam, situated to the south of India.

The Tamil epics Shilappadikaram and Manimekhalai provide glorious

descriptions of the legendary city and port of Puhar, which the

second text says was swallowed by the sea.

As in the case of Dwaraka,

(please refer to chapter on Dwaraka and Aryan Invasion Theory),

initial findings at and off Poompuhar, at the mouth of the Cauvery,

show that there may well be a historical basis to this legend: apart

from several structures excavated near the shore, such as brick

walls, water reservoirs, even a wharf (all dated 200-300 B.C.), a

few years ago a structure tantalizingly described as a "U-shaped

stone structure" was found five kilometers offshore, at a depth of

twenty-three meters; it is about forty meters long and twenty wide,

and fishermen traditionally believed that a submerged temple existed

at that exact spot. If the structure is confirmed to be man-made

(and not a natural formation), its great depth would certainly push

back the antiquity of Puhar.

Only more systematic explorations along

Tamil Nadu's coast, especially at Poompuhar, Mahabalipuram, and

around Kanyakumari (where fishermen have long reported submerged

structures too) can throw more light on the lost cities, and on the

traditions of Kumari Kandam, which some have sought to identify with

the mythical Lemuria).

ancient city in India.

We have the account of a Cera King conquering the Kadamba in the

midst of sea waters. The Cera King Senguttuvan had a fleet with

which he defeated the Yavanas who were punished with their hands

being tied behind their backs and the pouring of oil on their heads.

The Cholas also maintained a strong fleet with which they not only

invaded and subjugated Lanka but also undertook overseas

expeditions. Among the conquests of Rajaraja, Lanka was one, and his

invasion of that island finds expression in the Tiruvalangadu

plates, where it is described as follows:

"Rama built, with the aid of the monkeys, a causeway over the sea

and then slew with great difficulty the king of Lanka by means of

sharp-edged arrows. But Rama was excelled by this (king) whose

powerful army crossed the ocean in ships and burnt the king of

Lanka."

Rajaraja also sent an expedition against the Twelve Thousand

Islands, obviously a reference to the Laccadives and Maldives.

Friendly embassies were also sent by the Chola king to China.

From the evidence of the Mahvamsa as well as from a few inscriptions

we are able to gather some information regarding the diplomatic

relations that existed between India and Sri Lanka. We have the

story of Vijaya and his followers occupying the island about 543

B.C. Vijaya was a prince of North India who was banished from the

kingdom by his father. Passing through the southern Magadha country

he sailed to Sri Lanka, according to the Rajavali, in a fleet

carrying more than 700 soliders, defeated the Yaksas inhabiting it,

and settled there permanently.

This story is illustrated in the Ajanta frescoes.

Numerous ships carried the troops of Rajendra to Sri Vijaya and its

dependencies which he conquered. Among the places conquered were

Pannai (Pani or Panei on the east coast of Sumatra), Malaiyur (at

the southern end of the Malay Peninsula), Mappappalam ( a place in

the Talaing country of Lower Burma), Mudammalingam (a place facing

the gulf of Siam), Nakkavaram (the Nicobar islands. Besides, active

trade was carried on between South India and China during this

period.

At the end of the 10th century the Chinese emperor sent a mission to

the Chola king with credentials under the imperial seal and

provisions of gold and piece-goods to induce the foreign traders of

the South Sea and those who went to foreign lands beyond the sea for

trade to come to China.

The facts clearly show that the Cholas maintained supremacy over the

sea and kept a strong and powerful navy which was useful not only

for carrying on extensive commerce with foreign countries but also

for conducting military expeditions. During the days of the

Kakatiyas of Warangal, Motupalle (Guntur District) was the chief

port, on the east coast. Ganapatideva, the Kakatiya ruler,

extirpated piracy on the sea and made the sea safe for commerce with

foreign countries like China and Zanzibar. This policy was pursued

by Rudramba, his daughter.

Vijayanagar kingdom also claimed supremacy over the sea. Since the

days of Harihara I the rulers of Vijayanagar took the title of the

Lord of the Eastern, Western and Southern oceans; and there were 300

ports in the empire. The activities of the Vijayanagar fleet on the

west coast are also referred to by the Portuguese in 1506.

The Vijayanagar kings sent friendly embassies to foreign courts. 'Bukka

I sent an embassy through his chief explainer to the court of Taitsu,

the King Emperor of China, with tributes and large presents, among

which was a stone which was valuable in neutralizing poison.

Accounts of Foreign Travelers to India

Coming to later times we have the account of Hiuen Tsang who notices

a fleet of 3,000 sail belonging to the King os Assam. There is

inscriptional evidence of the possession of a fleet under the

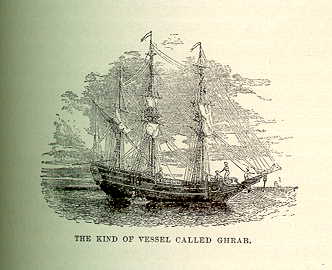

Kakatiyas and the Cholas in South india. Marco Polo testifies to the

huge size and efficient construction of Indian vessels while Yule in

his Cathey refers to Rajput ships en route to China.

Marco Polo, a

famous Venetian traveler who visited India in 13th Century also

visited Thane Port. The first chapter of his book which deals with

India is almost devoted to shipbuilding industry in India. Friar Odoric of Pordenone, an Italian Monk who visited India in 14th

Century, in his account of his voyage across the Indian Ocean, a

mention is made of ships which can carry 700 people.

"Ships of size that carried Fahien from India to China (through

stormy China water) were certainly capable of proceeding all the way

to Mexico and Peru by crossing the Pacific. One thousand years

before the birth of Columbus Indian ships were far superior to any

made in Europe upto the 18th century."

(source:

The Civilizations of Ancient America: The Selected Papers

of the XXIXth International Congress of Americanists - edited Sol

Tax 1951).

Ludovico di Varthema (1503 A. D) saw vessels of 1,000 tons burden

built at Masulipatnam. According to Dr. Vincent, India built great

sized vessels from the time of Agathareids (171 B.C.) to the 16th

century. And no wonder the Portuguese, when they first landed at the

west coast, were carried away by the excellent Indian vessels. Later

still, the Vijayanagar Empire, which had as many as 300 ports, had a

powerful fleet. The naval commander was styled Naviyadaprabhu.

India has a coastline of about 6300 km. Extensive new

archaeological, epigraphical, sculptural and literary material has

been added to our knowledge since the early decades of this century.

Dr. Radha Kumud Mookerji's Book

Indian Shipping - A History of the

Sea-Borne Trade and Marine Activity of The Indians From The Earliest

Times published in 1912 Orient, is the most

comprehensive study of Indian Navigation up to that period.

We now

know that many ports on both Eastern and Western Coast had

navigational and trade links with almost all Continents of the

world. There are many natural and technological reasons for this.

Apart from Mathematics and Astronomy, India had excellent

manufacturing skills in textile, metal works and paints. India had

abundant supply of Timber. Indian - built ships were superior as

they were built of Teak which resists the effect of salt water and

weather for a very long time.

"The art of Navigation was born in river Sindhu 6000 years ago. The

very word navigation is derived from Sanskrit word Nav (or Nav-ship)

Gatih."

Lieut. Col. A.Walker's paper: "Considerations of the affairs of

India" written in 1811 had excellent remarks on Bombay-built ships.

He notes,

"situated as she is between the forests of Malabar and

Gujarat, she receives supplies of timber with every wind that

blows."

Further he says, "it is calculated that every ship in the

Navy of Great Britain is renewed every twelve years. It is well

known that teakwood built ships last fifty years and upwards. Many

ships Bombay-built after running fourteen or fifteen years have been

brought into the Navy and were considered as stronger as ever. The

Sir Edward Hughes performed, I believe, eight voyages as an Indiaman

before she was purchased for the Navy. No Europe-built Indiaman is

capable of going more than six voyages with safety."

He has also further noted that Bombay-built ships are at least

one-fourth cheaper than those built in the docks of England.

Francois Balazar Solvyns, a Belgian/Flemish maritime painter, wrote

a book titled Les Hindous in 1811.

His remarks are,

"In ancient times, the Indians excelled in the art

of constructing vessels, and the present Hindus can in this respect

still offer models to Europe-so much so that the English, attentive

to everything which relates to naval architecture, have borrowed

from the Hindus many improvement which they have adopted with

success to their own shipping.... The Indian vessels unite elegance

and utility and are models of patience and fine workmanship."

(source:

http://www.orientalthane.com/speeches/speech_2.htm).

Surprisingly, many earlier western traders and travelers have

expressed the same views. Madapollum was a flourishing shipping

centre. Thomas Bowrey, an English traveler who visited India during

1669-79, observes,

"many English merchants and others have their

ships and vessels yearly built (at Madapollum). Here is the best and

well grown timber in sufficient plenty, the best iron upon the

coast, any sort of ironwork is ingeniously performed by the natives,

as spikes, bolts, anchors, and the like. Very expert master-builders

there are several here, they build very well, and launch with as

much discretion as I have seen in any part of the world. They have

an excellent way of making shrouds, stays, or any other rigging for

ships".

A Venetian traveler of 16th Century Cesare de Federici, while

commenting on the East Coast of India has noted that there is an

abundance of material for ship building in this area and many

Sultans of Constantinople found it cheaper to have their vessels

built in India than at Alexandria.

Nicolo Conti who visited India in 15th century was impressed by the

quality Indians had achieved in ship building. He observes:

"The nations of India build some ships larger than ours, capable of

containing 2,000 butts, and with five sails and as many masts. The

lower part is constructed with triple planks, in order to withstand

the force of the tempests to which they are much exposed. But some

ships are so built in compartments that should one part be

shattered, the other portion remaining entire may accomplish the

voyage."

J. Ovington, Chaplain to the British King, the seventeenth-century

English traveler, who visited Surat, wrote a book A Voyage to Surat

in the Year 1689. He was impressed by the skill of the Indians in

ship-building and found that they even outshone Europeans. The

timber used by the Indians was so strong that it would not ‘crack’

even by the force of a bullet so he urged the English to use that

timber ‘to help them in war’. Indian Teak stood firmer than the

English Oak, remarked Ovington.

Thomas Herbert, a traveler who visited Surat in 1627, has given an

interesting account of the arrival, loading and unloading of ships

through small boats at Swally marine (Sohaly), a few kilometres away

from Surat. He remarked that between September and March every year,

the port of Sohaly presented a very busy and noisy scene for there

came many ships from foreign lands. The merchants (baniyas) erected

their straw huts in large numbers all along the sea coast, making

the whole place thus look like a country fair. The merchants sold

various commodities like calicoes, ivory, agates, etc.

Many small

boys engaged by the merchants were seen running about doing odd

jobs. The English found that the small boats used and constructed by

the natives could be of immense use. This was a definite gain for

both nations. Boats and rafts were used as a means of conveyance for

loading and unloading ships. There were about 4200 big and 4400

small boats. There were large-sized boats that could carry even

elephants. The boats used by kings and nobles were designed to look

artistic.

Abul Fazl writes about the "wonderfully fashioned boats

with delightful quarters and decks and gardens"

Among the primitive Indian boats, the cattarmaran comes first. It

consisted of three logs and three spreaders and cross lashings. The

centre log was the largest, and pointed towards one end. Mainly

fishermen used the cattarmaran for fishing. A little more skillfully

made is the musoola boat, which has no iron fastening. It was mostly

used in the Coromandel coast.

Dr John Fryer says,

"It is possible

that the name musoola may be connected with Masulipatarn where boats

seem to have been in use".

Another boat made in an indigenous manner was known as dingy. It was

hollowed out from a single trunk. Lower down the Ganga, the name was

applied to boats half-decked, half wagon-roofed and built of planks.

Purqoo was another type of boat described by Thomas Bowery. It plied

between the Hooghly and Balasore. These boats were made very strong

to carry ‘sufficient load’. They were also used for loading ships.

they could remain in water for a long time without getting damaged.

As compared to the purqoo, boora was a ‘lighter boat’ which rowed

with 29 or 30 oars. These boats were also used for carrying

saltpeter and other commodities.

(source:

Coastal trade flourished with Europeans - By Pramod Sangar).

Sir John Malcolm (1769 - 1833) was a Scottish soldier, statesman,

and historian entered the service of the East India Company wrote

about Indian vessels that they:

"Indian vessels are so admirably adapted to the purpose for which

they are required that, notwithstanding their superior science,

Europeans were unable, during an intercourse with India for two

centuries, to suggest or to bring into successful practice one

improvement."

(source: Journal of Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. I and India and

World Civilization - By D P Singhal part II p. 76 - 77).

In the middle of the 18th century, John Grose noted that at Surat

the Indian ship-building industry was very well established, indeed,

“They built incomparably the best ships in the world for duration”,

and of all sizes with a capacity of over a thousand tons. Their

design appeared to him to be a “a bit clumsy” but their durability

soundly impressed him. They lasted “for a century”.

Lord Grenville mentions, in this connection, a ship built in Surat

which continued to navigate up the Red Sea from 1702 when it was

first mentioned in Dutch letters as “the old ships” up to the year

1700.” Grenville also noted that ships of war and merchandise “not

exceeding 500 tons” were being built” with facility, convenience and

cheapness” at the ports of Coringa and Narsapore.

Dr. H. Scott sent samples of dammer to London, as this vegetable

substance was used by the Indians to line the bottom of their ships;

he thought it would be a good substitute,

“in this country for the

materials which are brought from the northern nations for our

navy…There can be no doubt that you would find dammer in this way an

excellent substitute for pitch and tar and for many purposes much

superior to them.”

source: Decolonizing History: Technology and Culture in India, China

and the West 1492 to the Present Day - By Claude Alvares p. 68-69).

Alain Danielou (1907- 1994) son of French aristocracy, author of

numerous books on philosophy, religion, history and arts of India

has written:

"India's naval dockyards, which belonged to the state, were famous

throughout history. The sailors were paid by the state, and the

admiral of the fleet hired the ships and crew to tradesmen for

transporting goods and passengers. When the British annexed the

country much later on, they utilized the Indian dockyards - which

were much better organized then those in the West - to build most of

the ships for the British navy, for as long as ships were made of

wood."

(source:

A Brief History of India - By Alain Danielou p. 106).

"...an Indian naval pilot, named Kanha, was hired by Vasco da Gama

to take him to India. Contrary to European portrayals that Indians

knew only coastal navigation, deep-sea shipping had existed in

India. Indian ships had been sailing to islands such as the Andamans,

Lakshdweep and Maldives, around 2,000 years ago. Kautiliya's

shastras describe the times that are good and bad for seafaring. In

the medieval period, Arab sailors purchased their boats in India.

The Portuguese also continued to get their boats from India, and not

from Europe. Shipbuilding and exporting was a major Indian industry,

until the British banned it. There is extensive archival material on

the Indian Ocean trade in Greek, Roman, and Southeast Asian

sources."

(source:

History of Indian Science & Technology).

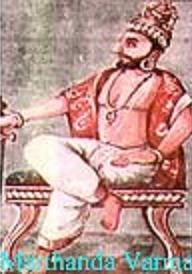

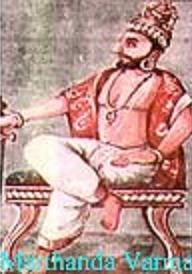

India became the first power to defeat a European power in a naval

battle - The Battle of Colachel in 1742 CE.

A dramatic and virtually unknown past, in an area of bucolic calm

surrounded by spectacular hills: that is Colachel, a name that

should be better known to us. For this is where, in 1741, an

extraordinary event took place -- the Battle of Colachel. For the

first, and perhaps the only time in Indian history, an Indian

kingdom defeated a European naval force.

The ruler of Travancore,

Marthanda Varma, routed an invading Dutch fleet; the Dutch

commander, Delannoy, joined the Travancore army and served for

decades; the Dutch never recovered from this debacle and were never

again a colonial threat to India.

The ruler of Travancore, Marthanda Varma, routed an invading Dutch

fleet;

the Dutch commander, Delannoy, joined the Travancore army and

served for decades;

the Dutch never recovered from this debacle and

were never again a colonial threat to India.

The Battle of Colachel in 1742 CE, where

Marthanda Varma of

Travancore crushed a Dutch expeditionary fleet near Kanyakumari. The

defeat was so total that the Dutch captain, Delannoy, joined the

Travancore forces and served loyally for 35 years--and his tomb is

still in a coastal fort there. So it wasn't the Japanese in the

Yellow Sea in 1905 under Admiral Tojo who were the first Asian power

to defeat a European power in a naval battle--it was little

Travancore.

The Portuguese and the Dutch were trying to gain

political power in India at that time. Marthanda Varma defeated the

Dutch in 1741. He was an able ruler. He established peace in his

country - Travancore. It was a remarkable achievement for a small

princely state.

(source:

The Battle of Colachel: In remembrance of things past - By

Rajeev Srinivasan - rediff.com and

http://www.kerala.com/kera/culture1.htm).

Back to Contents

Diplomacy and

War

Not withstanding the elaborate rule of war laid down in the epics

and the law-books, insisting in the main that to wage war was the

duty and privilege of every true Ksatriya, in several cases the

horrors of war made the belligerent think of the consequences and

avoid outbreak of hostilities by a well calculated policy which we

now term diplomacy.

King seeking counsel.

Negotiation, persuasion and conciliation were cardinal points of the

ancient Indian diplomatic system, and were effective instruments in

averting many a war, which would otherwise have realized in much

bloodshed and economic distress.

The political term for diplomacy is naya, and the opinion of

Kautalya, the eminent politician of the 4th century B.C., a king who

understands the true implications of diplomacy conquers the whole

earth.

The history of diplomacy in ancient India commences with the Rig

Veda Samhita, and the date of its composition may be taken as far

back as the Chalcolithic period. In the battles the help of Agni is

invoked to overcome enemies. He is to be the deceiver of foes. In

pursuing his mission to a successful end, the use of spies is

mentioned. This bears eloquent testimony to the system of espionage

prevalent so early as the time of the Rig Veda Samhita. In the

battle of the Ten Kings described in the seventh mandala, we find

diplomacy of rulers getting supplemented by its association with

priestly diplomacy, which exercised a healthy influence on the

constitutional evolution.

International Relations - The picture presented in the epics and the

Arthasastra literature seems to be confined to the four corners of

Bharatkhanda. The intercourse as envisaged in the literature, shows

relations to be more commerical than political in character.

Strabo quotes Megasthenes and says that Indians were not engaged in

wars with foreigners outside India nor was their country invaded by

foreign power except by Hercules and Dionsysius and lately by the

Macedonians. There were friendly relations of Chandragupta with

Seleukos Nikator, of Bindusara with Antiochus, of Asoka and

Samadragupta with Lanka, of Pulaskesi with Persians, of Harsha with

Nepal and China, of the Cholas with Sri Vijaya.

"It was always regarded as a legitimate object of the ambition of

every king to aim at the position of Cakravartin or Sarvabhuuma

(paramount sovereign or of supreme monarch)."

This ambition was

legitimate and had no narrow outlook about it. It was a fruit to be

sought after by every one of the monarchs comprising the mandala. If

the king is not actuated by this idea, he falls short of an ideal

king according to the Hindu Rajadharma.

Diplomatic agents - ambassadors

Bhisma mentions seven qualifications as essential in an ambassador:

he should come from a noble line, belong to a high family, be

skilful, eloquent of speech, true in delivering the mission, and of

excellent memory.

Espionage in War

Spies filled an important role in both the civil

and military affairs of ancient India. The institution of spies had

a greater utility, as the king could take action on the report of

the spies. Spies were engaged to look after the home officials,

including those of the royal household as well as to report on the

doings in the enemy kingdoms. The Rig Veda Samhita, often speaks of

spies (spasah) of Varuna.

Only men of wisdom and purity were sent on

this errand, thus suggesting that they should be persons above

corruption and temptation of any sort. In the epics and post-epic

literature in general, spies have been described as the 'eyes of the

king'. In the Udyoga-parva (33, 34) of Mahabharata, it is stated

that "cows see by smell, priests by knowledge, kings by spies, and

others through eyes."

Spies roamed about in foreign states under

various disguises to collect reliable information. In the Ramayana,

a king mentions the wise adage that "the enemy, whose secrets have

been known through espionage, can be conquered without much effort."

The Arthashastra, which predates Christ by centuries, dwells at

length on the importance of espionage and the creation of an

effective spy network.

Such details may indicate the high development of the science of

diplomacy in ancient India. It was the famous Indian strategist of

the fourth-century B.C, Kautilya in the Arthasastra, who gave the

world the dictum:

"The enemy of my enemy is my friend."

"The same style of Indian thought" says Heinrich Zimmer in his book,

Philosophies of India, p. 139, admiringly of Kautilya, "that

invented the game of chess grasped with profound insight the rules

of this larger game of power."

Attitude to war

The Sangam age of the Tamils was the heroic age of

the Tamil Indians. If the men of the Tamil land were heroes, then

their women were heroines. A certain mother was asked where her son

was, and she replied, that she was sure that the tiger that had lain

in her womb would be found in the field of battle. War was the

pabulum on which our ancient warriors were great in name and fame.

A

certain lady who gave birth to only one son and who sent him to the

field of battle when there was the country's call for it.

Okkurmasattiyar, a poetess, praises a certain lady dresses the hair

of her only son and gives him the armor to get ready for action in

the field of battle. This may be contrasted with another where a

heroic mother heard the disquieting news that her son lost his

courage in action and had fled in fear.

If it were true, she

expressed that she would cut off her breasts that had fed him with

milk. With this determination she entered the battle-field with

sword in her hand and went on searching for her fallen son. When she

saw her son's body cut in twain, she felt much more happy than when

she gave birth to him. (source: Puram 277 and 279 - in Tamil ).

Flags - The origin and use of flags can be traced to the earliest

Indian literature, the Rig Veda Samhita. The term deaja occurs twice

in the Veda. Besides, dhvaja, we meet with a good number of

expressions for a banner in Vedic literature. These are Akra,

Krtadhvaja, Ketu, Brhatketu, Sahasraketu. It appears that the Vedic

host aimed their arrows at the banners of the enemy.

The idea was

that once the banner was captured, or struck, a claim was made for

success in the battle over the enemy. Ketu was a small flag as

contrasted with Brhatketu or the big flag. Sahasraketu may be a

thousand flag, or as the knight who brought under control a thousand

flags of enemies. We are told that banners and drums were counted

among the insignia of ancient Vedic kings. In the Mahabharata war,

every leader had his own insignia to distinguish one division from

the other.

Arjuna had the Kapidhvaja or the flag with the figure of

Hanuman, Bhisma, Taladhvaja, cognizance of a palmyra tree etc..

Back to Contents

|

forth his monkey hosts in quest of Sita.

forth his monkey hosts in quest of Sita.